201209 Final Thesis Amended.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold in Antique Copper Alloys

Gold in Antique Copper Alloys Paul T. Craddock cent of either gold or silver would make to the appearance of Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. the copper. However, although we can accept the story of its accidental discovery two centuries before Pliny's time as Lost continents, lost cities and fabulous materials from past apocryphal it is difficult to dismiss the latter's description of ages have a natural fascination for scholar and layman alike. its popularity with collectors and its high value in his own Since the Renaissance, men have sought examples of Corin- time. It would seem that in Pliny's day the term Corinthian thian Bronze, the precious alloy much extolled by antient Bronze was used to describe a group of alloys which were writers and have tried to establish its nature. As indicative of readily distinguished and appreciated, and for which attitudes towards it, Thomas Corayte (1) described the bronze collectors were willing to pay a high price. horses of San Marco in Venice as being 'a remarkable monu- The first step towards recognizing surviving examples of ment, four goodly brazen horses of Corinthian metal and this material was, of course, to have some idea of its fully as great as life' , apparently for no better reason than that appearance. Small quantities of gold and silver incorporated he thought such noble statuary demanded the most prized in copper are known to have a dramatic effect on the resulting bronze metal of them all. Further, in Pliny's 'Natural alloys if they are subsequently treated in a suitable manner. -

Greek Bronze Yearbook of the Irish Philosophical Society 2006 1

Expanded reprint Greek Bronze 1 In Memoriam: John J. Cleary (1949-2009) Greek Bronze: Holding a Mirror to Life Babette Babich Abstract: To explore the ethical and political role of life-sized bronzes in ancient Greece, as Pliny and others report between 3,000 and 73,000 such statues in a city like Rhodes, this article asks what these bronzes looked like. Using the resources of hermeneutic phenomenological reflection, as well as a review of the nature of bronze and casting techniques, it is argued that the ancient Greeks encountered such statues as images of themselves in agonistic tension in dynamic and political fashion. The Greek saw, and at the same time felt himself regarded by, the statue not as he believed the statue divine but because he was poised against the statue as a living exemplar. Socrates’ Ancestor Daedalus is known to most of us because of the story of Icarus but readers of Plato know him as a sculptor as Socrates claims him as ancestor, a genealogy consistently maintained in Plato’s dialogues.1 Not only is Socrates a stone-cutter himself but he was also known for his Daedalus-like ingenuity at loosening or unhinging his opponent’s arguments. When Euthyphro accuses him of shifting his opponents’ words (Meletus would soon make a similar charge), Socrates emphasizes this legacy to defend himself on traditionally pious grounds: if true, the accusation would set him above his legendary ancestor. Where Daedalus ‘only made his own inventions to move,’ Socrates—shades of the fabulous Baron von Münchhausen—would thus be supposed to have the power to ‘move those of other people as well’ (Euth. -

Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists DavidM Jacobson The Centre fOr RapidDesign and Manufacture, Buckingham Chilterns University College, High Wycombe, HP11 2JZ, UK Received: 1 July 1999 Alloys that went under the name of Corinthian Bronze were highly prized in the Roman Empire at the beginning of the Christian era, when Corinthian Bronze was used to embellish the great gate of Herod's Temple in Jerusalem. From the ancient texts it emerges that Corinthian Bronze was the name given to a family of copper alloys with gold and silver which were depletion gilded to give them a golden or silver lustre. An important centre of production appears to have been Egypt where, by tradition, alchemy had its origins. From an analysis of the earliest alchemical texts, it is suggested that the concept of transmutation of base metals into gold arose from the depletion gilding process. CORINTHIAN BRONZE AND ITS main constituent because it is classified as bronze (aes IDENTIFICATION in Latin), and is discussed by Pliny in the section of his encyclopaedia dealing with copper and bronze. Ancient texts in Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Syriac refer However, Pliny indicates that their hue varied from to a type of metal called Corinthian Bronze which they golden to silvery, depending on the proportions of the prize above all other copper alloys. The Roman precious metal additions, and it was this lustre that encyclopaedist, Pliny, who lived in the 1st century AD, gave this bronze its attractive appearance. -

Technical Studies on the Roman Copper-Based Finds from Emona

Berliner Beiträge zur Archäometrie Seite 5-42 2001 Technical sturlies on the roman copper-based finds from Emona ALESSANDRA ÜIUMLIA-MAIR Universita di Udine, Corso di Diploma Universitario per Operatoredei Beni Culturali, Indirizzo Archeologico, Gorizia. Palazzo Alvarez, via Diaz 5 I - 34170 GORIZIA Introduction This research was initiated at the beginning of the nineties, as an explorative study of the material. A first report was published in the Bulletin of the Metals Museum, Sendai, Japan (Giumlia-Mair 1996) and two short discussions on some aspects ofthe research were presented in 1996 at the 13th Bronze Conference at Cambridge Massachussets (in publ.), as an appendix to the papers given by Dr Ljudmila Plesnicar Gec (in publ.) and Mag. lrena Sivec (in publ.), Mestni Muzej Ljubljana. This paper presents now the complete study for the first time. A choice of Roman copper-based objects from Ljubljana, now in the Mestni Muzej (Municipal Museum) have been sampled and analysed. The objects come from various excavations carried out in the last decades in the area ofthe ancient Roman town Emona and are dated to the period between the 1st c. BC and the 5th c. AD (Piesnicar Gec 1972; 1983; 1992; 1996 with further bibliography; 2000; Sivec 1992; 1996; 1998; 2000 andin publ.). The earlier finds seem to indicate mining activities in the region and the presence of metalworkers and organized workshops in the Settlements (Giumlia-Mair 1995, 1998 band c). The stylistic characteristics of the autochthonaus production arestill clearly recognizable in various artifacts of the Roman period and suggest a continuity of the metallurgical activities in the area. -

Luxury at Rome: Avaritia, Aemulatio and the Mos Maiorum

Roderick Thirkell White Ex Historia 117 Roderick Thirkell White1 University College London Luxury at Rome: avaritia, aemulatio and the mos maiorum This article sets out to put into perspective the ancient Roman discourse about luxury, which our extant literary sources almost universally condemn, on moral grounds. In it, I aim to define the scope and character of Roman luxury, and how it became an issue for the Romans, from the end of the third century BC to the beginning of the second century AD. With the aid of modern thinking about luxury and the diffusion of ideas in a society, I shed light on the reasons for the upsurge in luxurious living and, in particular, on how luxuries spread through the elite population, an issue that has been largely neglected by modern scholars. Books and articles on Roman luxury have been primarily concerned with examining the discourse of contemporary writers who criticised luxury;2 analysing the nature of Roman luxury;3 analysing the nature and impact of sumptuary legislation;4 or comparing the luxury of the Romans with that of other cultures.5 The only significant article dealing specifically with the diffusion of luxury is a provocative piece by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, the focus of which is, however, limited and specific.6 For a series of moralising Roman authors, the second century BC saw the beginning of the corruption of the traditional stern moral fibre, as they saw it, of the Republic by an influx of 1 Roderick Thirkell White’s academic interests are concerned with aspects of the economy of the ancient world, primarily the late Roman Republic and Early Empire, with a focus on consumer and material culture. -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

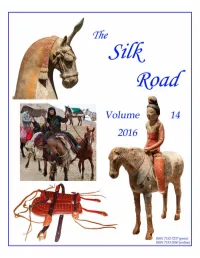

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

Corinthian Metalworking: the Forum Area

CORINTHIAN METALWORKING: THE FORUM AREA (PLATES 99-104) T 5HE Corinthianmetalworking industry commandedwidespread respect in an- tiquity, and the bronzes that were produced in Corinth were admired and sought after throughout the ancient world.' Pliny wrote that Corinthian bronze was valued more highly than silver (N.H. 34.1, 34.6-8, 34.48), and even suggested that it was alloyed with gold and silver (N.H. 37.49). Pausanias tried to explain the extraordinary color of Corinthian bronze by saying that it was quenched in the waters of Peirene (11.3.3).2 The archaeological evidence for this flourishing indus- try is limited, but the discovery of metallurgical remains of all periods in the Forum Area indicate that both large- and small-scale projects were undertaken here, involv- ing the use of both bronze and iron. WORKSHOPS There are few traces of actual workshops; the only large-scale bronze foundry is located to the north of Temple G (Fig. 1).' A pit is cut in the bedrock in the shape of a keyhole, measuring 2.20 X 1.70 m. at ground level and up to 1.50 m. deep. At the south side of the wide west end of the pit there is a steep stairwvay,'with 1 I am grateful to Charles K. Williams, II for permission to study the Corinthian metallurgical remains, for his advice and criticisms, and in particular for allowing me to participate in the excava- tion of three different areas where evidence for metalworking was being uncovered during the 1972 season. Also I am indebted to Nancy Bookidis for her suggestions about the material, and for the preparation of the plhotographs. -

Corinthian Bronze

Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. 14.10 Corinthian Bronze One of the most highly valued metals of the Roman world was Corinthian bronze, a compound of gold and silver mixed with either copper or bronze. The metal was produced in Corinth and used throughout that city to gild the tops of columns that were carved in a distinctive floral pattern. Corinthian columns (with or without the decorative overlay) became famous throughout the empire. The origin of Corinthian bronze is lost in legend, but all sources agree that it was invented by accident. Plutarch reports that a house containing the right proportions of gold, silver, and copper caught fire, and the three metals melted together to yield a happy surprise (Oracles 395.2). Petronius says that the Carthaginian general Hannibal produced the first batch when he destroyed the city of Ilium and burned its treasures (Satyricon 50). Whatever the metal’s origin, the Roman philosopher Seneca expresses sardonic disgust for consumers who were so driven by the metal’s faddish popularity that they would pay outlandish prices to own anything made of Corinthian bronze (On Shortness of Life 12.2; Helvia on Consolation 11.3). Seneca was the brother of Gallio, the proconsul of Achaia mentioned in Acts 18:12–17. Gallio was a wealthy and powerful citizen of Corinth, and we probably can Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. assume that he had a different attitude toward avid consumers of his city’s chief export than that expressed by his intellectual sibling. -

Ziff, Magic Goggles, and Golden Plates

Ziff, Magic Goggles, and Golden Plates Etymology of Zyf and a Metallurgical Analysis of the Book of Mormon Plates Jerry D. Grover, Jr. PE, PG ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ZIFF,%MAGIC%GOGGLES,% AND%GOLDEN%PLATES% ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! % ZIFF,%MAGIC%GOGGLES,%% AND%GOLDEN%PLATES% ! The%Etymology%of%Zyf%and%a%Metallurgical%Analysis%of%the% Book%of%Mormon%Plates% % % by% Jerry%D.%Grover,%Jr.%PE,%PG% % % ! ! ! ! ! Jerry!D.!Grover,!Jr.,!is!a!licensed!Professional!Structural!and!Civil!Engineer!and!a!licensed!Professional!Geologist.!He! has!an!undergraduate!degree!in!Geological!Engineering!from!BYU!and!a!Master’s!Degree!in!Civil!Engineering!from! the!University!of!Utah.!He!speaks!Italian!and!Chinese!and!has!worked!with!his!wife!as!a!freelance!translator!over! the!past!25!years.!He!has!provided!geotechnical!and!civil!engineering!design!for!many!private!and!public!works! projects.!He!took!a!12Lyear!hiatus!from!the!sciences!and!served!as!a!Utah!County!Commissioner!from!1995!to!2007.! He!is!currently!employed!as!the!site!engineer!for!the!remediation!and!redevelopment!of!the!1750Lacre!Geneva! Steel!site!in!Vineyard,!Utah.! ! ! Acknowledgments:!!I!am!thankful!for!the!excellent!professional!editing!provided!by!Sandra!Thorne.!!I!enjoyed!the! encouragement!provided!by!Dr.!John!L.!Sorenson.!!The!Semitic!language!research!assistance!of!David!Calabro!was! also!greatly!helpful.!!And!finally!to!my!wife!and!kids,!for!their!patient!attentiveness!during!my!excited!dinner!table! diatribes!about!the!exciting!processes!of!depletion!gilding.! ! ! ! Grover!Publishing,!PO!Box!2113,!Provo,!Utah!84606! -

Technology Transfer from Ancient Egypt to the Far East?

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER FROM ANCIENT EGYPT TO THE FAR EAST? Alessandra R. Giumlía-Mair AGM Archeoanalisi Merano, Italy ery special black patinated alloys were employed Sea area in the 5th – 4th century BCE (Giumlia-Mair and V in the western ancient world for exceptionally La Niece 1998). Only later — in the Roman period and precious objects. After the fall of the Roman Empire until modern times — did it become common and was they were lost and forgotten in the West, but they employed mainly on small decorative objects. The survived in Asia. In Southern China they are known fact that the decoration on the Mycenean daggers is as wu tong. The same material is called VKDNXGż in an altogether different material came as a surprise for Japan, where it is considered characteristic of Japanese the world of archaeology. After the fall of the Roman metal art. Related patinated alloys of different colours Empire, the black patinated material is mentioned in were employed in Roman Egypt and are found in Syria. There are hints of its existence in Persia, India 19th century Japan too. This paper will explore the DQG7LEHWLWLVGHÀQLWHO\SUHVHQWLQ&KLQD.RUHDDQG possibility of and means of technology transfer Myanmar; and it reaches the peak of its fame in Japan, from Egypt to Asia by examining the appearance, where it was employed on metalwork until the Meiji composition, manufacture and characteristics of the period. YDULRXV ÀQGV IURP WKH HDUOLHVW WR WKH ODWHVW LQ WKHLU Patinated alloys historical contexts. Readers can expect a fair amount of technical detail about the composition of alloys, but 7KH PDWHULDOV GLVFXVVHG LQ WKLV SDSHU DUH DUWLÀFLDOO\ without this kind of evidence, it is impossible to make patinated copper-based alloys containing small the connections. -

Ziff, Magic Goggles, and Golden Plates

ZIFF, MAGIC GOGGLES, AND GOLDEN PLATES The etymology of zyf and a metallurgical analysis of the Book of Mormon plates By Jerry D. Grover, Jr. PE, PG Draft Copyright 2015 Introduction One day while viewing various internet videos involving the Book of Mormon, I happened across a video from the 2005 FAIR Conference on Archaeology and The Book of Mormon, which involved a joint presentation by Dr. John Clark, Matthew Roper, and Wade Ardern. As part of the presentation, Matthew Roper displayed some slides indicating various Book of Mormon items as “unknowable” because they were “logically beyond proof or disproof” as it is not known “what they are in the real world”. Chief among those listed by Mr. Roper was the “famous but mysterious metal ziff”, with Mr. Roper citing from the 19th Century anti-Mormon Origen Bacheler. Bacheler made the following challenge as documented in his publication Mormonism Exposed Internally and Externally: "And what kind of metal is ziff! Come, Joseph, on with thy goggles, and translate thy translation, and tell us what ziff means." (Origen, 1838) Mr. Roper received a spirituous chuckle from the FAIR audience, so I assumed that ‘ziff’ may have just become an inside joke among professional Book of Mormon research enthusiasts. Having just completed a few years of research that resulted in the publication of the book Geology of the Book of Mormon, I had been surprised by just how little real scientific research had been completed in relationship with the Book of Mormon with regards to its geological references. I wondered if Mr. -

1-2 Corinthians

P1:IwX/KNP 0521834627agg.xml CB864/Keener 0521834627 April 11, 2005 12:45 This page intentionally left blank ii P1:IwX/KNP 0521834627agg.xml CB864/Keener 0521834627 April 11, 2005 12:45 1–2 corinthians This commentary explains 1 and 2 Corinthians passage by passage, following Paul’s argument. It uses a variety of ancient sources to show how Paul’s argument would have made sense to first-century readers, drawing from ancient letter-writing, speak- ing, and social conventions. The commentary will be of interest to pastors, teachers, and others who read Paul’s letters, because of its readability, firm grasp of the background and scholarship on the Corinthian correspondence, and its sensitivity to the sorts of questions asked by those wishing to apply Paul’s letters today. It also will be of interest to scholars because of its exploration of ancient sources, often providing sources not previously cited in commentaries. Craig S. Keener is a professor of New Testament at Eastern Seminary, a division of Eastern University. His previous twelve books include three award-winning commentaries: The Gospel of John: A Commentary, A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, and The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament. i P1:IwX/KNP 0521834627agg.xml CB864/Keener 0521834627 April 11, 2005 12:45 ii P1:IwX/KNP 0521834627agg.xml CB864/Keener 0521834627 April 11, 2005 12:45 new cambridge bible commentary general editor:Ben Witherington III hebrew bible/old testament editor:Bill T. Arnold editorial board Bill T. Arnold, Asbury Theological Seminary James D. G. Dunn, University ofDurham Michael V.