Technology Transfer from Ancient Egypt to the Far East?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold in Antique Copper Alloys

Gold in Antique Copper Alloys Paul T. Craddock cent of either gold or silver would make to the appearance of Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. the copper. However, although we can accept the story of its accidental discovery two centuries before Pliny's time as Lost continents, lost cities and fabulous materials from past apocryphal it is difficult to dismiss the latter's description of ages have a natural fascination for scholar and layman alike. its popularity with collectors and its high value in his own Since the Renaissance, men have sought examples of Corin- time. It would seem that in Pliny's day the term Corinthian thian Bronze, the precious alloy much extolled by antient Bronze was used to describe a group of alloys which were writers and have tried to establish its nature. As indicative of readily distinguished and appreciated, and for which attitudes towards it, Thomas Corayte (1) described the bronze collectors were willing to pay a high price. horses of San Marco in Venice as being 'a remarkable monu- The first step towards recognizing surviving examples of ment, four goodly brazen horses of Corinthian metal and this material was, of course, to have some idea of its fully as great as life' , apparently for no better reason than that appearance. Small quantities of gold and silver incorporated he thought such noble statuary demanded the most prized in copper are known to have a dramatic effect on the resulting bronze metal of them all. Further, in Pliny's 'Natural alloys if they are subsequently treated in a suitable manner. -

Greek Bronze Yearbook of the Irish Philosophical Society 2006 1

Expanded reprint Greek Bronze 1 In Memoriam: John J. Cleary (1949-2009) Greek Bronze: Holding a Mirror to Life Babette Babich Abstract: To explore the ethical and political role of life-sized bronzes in ancient Greece, as Pliny and others report between 3,000 and 73,000 such statues in a city like Rhodes, this article asks what these bronzes looked like. Using the resources of hermeneutic phenomenological reflection, as well as a review of the nature of bronze and casting techniques, it is argued that the ancient Greeks encountered such statues as images of themselves in agonistic tension in dynamic and political fashion. The Greek saw, and at the same time felt himself regarded by, the statue not as he believed the statue divine but because he was poised against the statue as a living exemplar. Socrates’ Ancestor Daedalus is known to most of us because of the story of Icarus but readers of Plato know him as a sculptor as Socrates claims him as ancestor, a genealogy consistently maintained in Plato’s dialogues.1 Not only is Socrates a stone-cutter himself but he was also known for his Daedalus-like ingenuity at loosening or unhinging his opponent’s arguments. When Euthyphro accuses him of shifting his opponents’ words (Meletus would soon make a similar charge), Socrates emphasizes this legacy to defend himself on traditionally pious grounds: if true, the accusation would set him above his legendary ancestor. Where Daedalus ‘only made his own inventions to move,’ Socrates—shades of the fabulous Baron von Münchhausen—would thus be supposed to have the power to ‘move those of other people as well’ (Euth. -

GIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-Crafted Treasures by Local Artists Holidaygift GUIDE 2020

HolidayGIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists HolidayGIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists Welcome to the first TAS Holiday Gift Guide 2020-curated by Talmadge Art Show producers, Sharon Gorevitz and Alan Greenberg. Shop with Talmadge Art Show artists virtually—anytime, anywhere! CONTACT THE ARTISTS DIRECTLY FOR ORDERS BY CLICKING ON A PRODUCT PHOTO, THEIR WEBSITE OR EMAIL LINKS. Be on the lookout for special emails about the TAS Holiday Questions? 619-559-9082 or [email protected] Gift Guide 2020 with information on specials, artists and crafts. Please enjoy this unique TAS Holiday Gift Guide 2020, however, it’s only live until December 31st. Happy Holidays… Sharon & Alan Holiday Gift Guide Table OF Contents JEWELRY 4-20 CERAMICS 21-27 MIXED MEDIA/FINE ART 28-30 WEARABLES 31-35 MATERIALS - WOOD, TILES, GLASS, METAL, FIBER, PAPER 36-41 PHOTOGRAPHY 42-43 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists Questions? 619-559-9082 or [email protected] TAS HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE 2020 JEWELRY | 4 ARTIST BIO Organic Jewelry by Allie have been in business since 2010and our mission is to create jewels with a good karma. Our jewelry is nature sourced and nature inspired and sometimes denounces with art and/or enviromental issues. Our processes are Alessandra Thornton characteristic of slow fashion, and leave minimal carbon foot print in the environment. LOCATION CONTACT INFO TEMECULA, CA Organic Jewelry by Allie /OrganicJewelrybyAllie MEDIUM organicjewelrybyallie.com | 858.449.6801 /alessandrathornton/ Tagua nut, rainforest seeds, leather and other organic mediums [email protected] /OrganicjewelrybyAlli Paw Necklace Set Marine Life Jewelry Set Tiger Necklaces This is a 3 piece set and Our beautiful ocean animals Beautiful Animal, tiger print includes paw bracelet for featured in our hand carved handpainted tagua nuts pet mom, dog tag for the tagua nuts bracelets and necklaces are part of my pet and paw necklace for earrings deserve clean new “Cougar” or “Tigresa” the pet father. -

201209 Final Thesis Amended.Pdf

“Cleanse out the Old Leaven, that you may be a New Lump”: A Rhetorical Analysis of 1 Cor 5-11:1 in Light of the Social Lives of the Corinthians Written by Sin Pan Daniel Ho March 2012 Supervisor: Professor James G. Crossley APartial FulFillment for the Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Biblical Studies. University of Sheffield This study offers a new interpretation of 1 Cor 5—11:1 from a social identity approach. The goal is to investigate and analyse the inner logic of Paul in these six chapters from the ears of the Corinthian correspondence. It takes into account the Jewish tradition inherited from Paul and daily social lives of the audience. Through the analysis of the literary structure of 1 Cor 5-11:1, research on social implications of Satanic language in ancient Jewish literature, rhetorical analysis of intertextual echoes of Scripture and Christ language in 1 Cor 5-11:1 in light of the social values prevalent in the urban city of Roman Corinth, it is argued that Paul has consistently indoctrinated new values for the audience to uphold which are against the main stream of social values in the surrounding society throughout 1 Cor 5-11:1. Paul does not engage in issues of internal schism per se, but rather in the distinctive values insiders should uphold so as to be recognisable by outsiders in their everyday social lives. While church is neither a sectarian nor an accommodating community, it should maintain constant social contact with the outsiders so as to bring the gospel of Christ to them. -

DIY Statement Necklace Making Ideas You'll Love

PRESENTS How to Make Necklaces: DIY Statement Necklace Making Ideas You’ll Love HOW TO MAKE NECKLACES: DIY STATEMENT NECKLACE MAKING IDEAS YOU’LL LOVE 7 DISCO DARLING Making the most of disc beads BY KEIRSTEN GILES 3 10 CHINESE WRITING MOKUME GANE STONE PENDANT HEART PENDANT Set an irregular stone Combine alternative metals with with pickets conventional materials BY LEXI ERICKSON BY ROGER HALAS NECKLACES COME IN ALL SHAPES AND SIZES, which is advantage of metal’s malleability to create a 3D heart one of the great things about them if you like developing pendant with mokumé gané, a layered metal whose your own jewelry designs. You can make other types of patterns stretch and compress as you form the heart jewelry in different styles from ancient to Edwardian to (create your own mokumé as shown with sterling, bronze, punk, too – you just have more ground to work with if and traditional alloys or buy sheet as metal stock), and you’re creating jewelry that’s worn around the neck. add a wink of sparkle with a small faceted gem. Or you can create your own pattern as you put together an Pendants are perfect for showing off interesting patterns impressive necklace using turquoise and wood button because you have enough room to show the whole pattern, beads linked together with copper wire and jump rings for a but pendants work just as well for something small, simple, and contemporary look on a traditional form. uniform. Like pendant necklaces, necklaces without a focal or with a focal area made of multiple elements can be as big or Start your next necklace making venture with these varied little as you or your customers like. -

Annual Report 2009

Bi-Annual 2009 - 2011 REPORT R MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Director’s Message With the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Harn Museum of Art in 2010 we had many occasions to reflect on the remarkable growth of the institution in this relatively short period 1 Director’s Message 16 Financials of time. The building expanded in 2005 with the addition of the 18,000 square foot Mary Ann Harn Cofrin Pavilion and has grown once again with the March 2012 opening of the David A. 2 2009 - 2010 Highlighted Acquisitions 18 Support Cofrin Asian Art Wing. The staff has grown from 25 in 1990 to more than 50, of whom 35 are full time. In 2010, the total number of visitors to the museum reached more than one million. 4 2010 - 2011 Highlighted Acquisitions 30 2009 - 2010 Acquisitions Programs for university audiences and the wider community have expanded dramatically, including an internship program, which is a national model and the ever-popular Museum 6 Exhibitions and Corresponding Programs 48 2010 - 2011 Acquisitions Nights program that brings thousands of students and other visitors to the museum each year. Contents 12 Additional Programs 75 People at the Harn Of particular note, the size of the collections doubled from around 3,000 when the museum opened in 1990 to over 7,300 objects by 2010. The years covered by this report saw a burst 14 UF Partnerships of activity in donations and purchases of works of art in all of the museum’s core collecting areas—African, Asian, modern and contemporary art and photography. -

Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection New York I September 12, 2018

Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection New York I September 12, 2018 Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection Wednesday September 12, 2018 at 10am New York BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS www.bonhams.com/25151 Takako O’Grady, Thursday September 6 Front cover: Lot 10 Administrator 10am to 5pm Back Cover: Lot 2 Friday September 7 Please note that bids should be +1 (212) 461 6523 summited no later than 24hrs [email protected] 10am to 5pm REGISTRATION prior to the sale. New bidders Saturday September 8 IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of Joe Earle Please note that all customers, Sunday September 9 identity when submitting bids. Senior Consultant irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in +44 7880 313351 with Bonhams, are required to Monday September 10 your bid not being processed. [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm Form in advance of the sale. The form Tuesday September 11 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS can be found at the back of every 10am to 3pm AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE catalogue and on our website at Please email bids.us@bonhams. -

Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists DavidM Jacobson The Centre fOr RapidDesign and Manufacture, Buckingham Chilterns University College, High Wycombe, HP11 2JZ, UK Received: 1 July 1999 Alloys that went under the name of Corinthian Bronze were highly prized in the Roman Empire at the beginning of the Christian era, when Corinthian Bronze was used to embellish the great gate of Herod's Temple in Jerusalem. From the ancient texts it emerges that Corinthian Bronze was the name given to a family of copper alloys with gold and silver which were depletion gilded to give them a golden or silver lustre. An important centre of production appears to have been Egypt where, by tradition, alchemy had its origins. From an analysis of the earliest alchemical texts, it is suggested that the concept of transmutation of base metals into gold arose from the depletion gilding process. CORINTHIAN BRONZE AND ITS main constituent because it is classified as bronze (aes IDENTIFICATION in Latin), and is discussed by Pliny in the section of his encyclopaedia dealing with copper and bronze. Ancient texts in Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Syriac refer However, Pliny indicates that their hue varied from to a type of metal called Corinthian Bronze which they golden to silvery, depending on the proportions of the prize above all other copper alloys. The Roman precious metal additions, and it was this lustre that encyclopaedist, Pliny, who lived in the 1st century AD, gave this bronze its attractive appearance. -

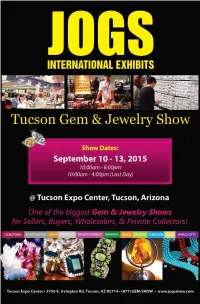

JOGS Show Guide F2015

2 | JOGS SHOW JOGS SHOW | 3 4 | JOGS SHOW TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION: PAGE: Show Floorplan ...................................................................................... 5 Show Terms & Policies ......................................................................... 6 List of Exhibitors ................................................................................... 12 JOGS SHOW | 5 6 | JOGS SHOW JOGS SHOW | 7 LET’S PROMOTE AMBER TOGETHER SHARE WITH US YOUR STORY! SO MANY EXHIBITIONS! SO MANY STANDS! HOW CAN A BUYER SEE YOU? BE VISIBLE! BE WITH THE BALTIC JEWELLERY NEWS! “Baltic Jewellery News” / Paplaujos str. 5–7, LT-11342 Vilnius, Lithuania / Tel./Fax +370 5 212 08 23 / E-mail: [email protected] 8 | JOGS SHOW www.balticjewellerynews.com JOGS SHOW | 9 10 | JOGS SHOW TUCSON JOGS SHOW SPECIAL %50 OFF IN TRADITIONAL SS RINGS JOGS SHOW | 11 List of Exhibitors 1645 JEWELRY 1645 W Ohio St Booth#: W422 Chicago, IL 60622 Custom Turkish jewelry, semiprecious USA stones with brass. Tel: 872-212-9950 ABSOLUTE JEWELRY MFG 4400 N Scottsdale Rd, #9205 Booth#: W615, W617, W516, W518 Scottsdale, AZ 85257 Sterling silver, handmade inlay jewelry. USA Tel: (480) 437-0411 AF DESIGN INC 1212 Broadway Booth#: W715, W717 NY, NY 10001 Manufacturer and Designer of Silver, USA Stainless Steel, Fashion, Marcasite Tel: 212 683 2559 Jewelry with Gemstones http://afdesigninc.com/ AFRICA GEMS USA 10 Muirfield Blvd. Booth#: W605, W607 Monroe TWP, NJ 8831 Semi-precious stone beads, rough USA stones. Tel: 732 572 6670 AMBERMAN 650 S Hill St, Ste 513 Booth#: W408, W410 Los Angeles, CA 90014 Amber jewelry set in sterling silver, USA beads, cameos. Tel: (213) 629-2112 www.amberman.com ANNA KING JEWELRY 112 Kimball Rd Booth#: W407 Ridge, NH 3461 Semi-precious stones and carvings from USA around the world as well as unusual Tel: 603-852-3375 items such as Russian hand painting www.annakingjewelry.com porcelain, glass, crystal and other catalyst items. -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

There Is a Silver Lining. Kaki D

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2003 There is a Silver Lining. Kaki D. Crowell-Hilde East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Crowell-Hilde, Kaki D., "There is a Silver Lining." (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 784. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/784 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. There Is A Silver Lining A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Kaki D. Crowell-Hilde August 2003 David G. Logan, Committee Chair Carol LeBaron, Committee Member Don R. Davis, Committee Member Keywords: Metalsmithing, Casting, Alloys, Etching, Electroforming, Raising, Crunch-raising, Patinas, Solvent Dyes ABSTRACT There Is A Silver Lining by Kaki D. Crowell-Hide I investigated two unique processes developed throughout this body of work. The first technique is the cracking and lifting of an electroformed layer from a core vessel form. The second process, that I named “crunch-raising”, is used to form vessels. General data were gathered through research of traditional metalsmithing processes. Using an individualized approach, new data were gathered through extensive experimentation to develop a knowledge base because specific reference information does not currently exist. -

Reliable Irogane Alloys and Niiro Patination—Further Study Of

Reliable irogane alloys and niiro patination—further study of production and application to jewelry JONES, Alan Hywel and O'DUBHGHAILL, Coilin Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/4331/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version JONES, Alan Hywel and O'DUBHGHAILL, Coilin (2010). Reliable irogane alloys and niiro patination—further study of production and application to jewelry. In: Santa Fe Symposium on Jewelry Manufacturing Technology 2010: proceedings of the twenty- fourth Santa Fe Symposium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Albuquerque, N.M., Met- Chem Research, 253-286. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Jones Reliable Irogane Alloys and Niiro Patination—Further Study of Production and Application to Jewelry Jones Dr. A. H. Jones Principal Researcher, Materials and Engineering Research Institute Dr. Cóilín Ó Dubhghaill Jones Senior Research Fellow, Art and Design Research Centre Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield, UK Jones Abstract Japanese metalworkers use a wide range of irogane alloys (shakudo, shibuichi), which are colored with a single patination solution (niiro eki).