Buddhist Heritage of Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

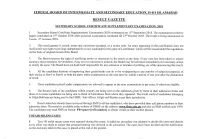

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

Ghazni of Afghanistan Issue: 2 Mohammad Towfiq Rahmani Month: October Miniature Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Herat University, Herat, Afghanistan

SHANLAX International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities s han lax # S I N C E 1 9 9 0 OPEN ACCESS Artistic Characters and Applied Materials of Buddhist Temples in Kabul Volume: 7 and Tapa Sardar (Sardar Hill) Ghazni of Afghanistan Issue: 2 Mohammad Towfiq Rahmani Month: October Miniature Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Herat University, Herat, Afghanistan Year: 2019 Abstract Kabul and Ghazni Buddhist Temple expresses Kushani Buddhist civilization in Afghanistan and also reflexes Buddhist religion’s thoughts at the era with acquisitive moves. The aim of this article P-ISSN: 2321-788X is introducing artistic characters of Kabul Buddhist temples and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni Buddhist Temple in which shows abroad effects of Buddhist religion in Afghanistan history and the importance of this issue is to determine characters of temple style with applied materials. The E-ISSN: 2582-0397 results of this research can present character of Buddhist Temples in Afghanistan, thoughts of establishment and artificial difference with applied materials. Received: 12.09.2019 Buddhist religion in Afghanistan penetrated and developed based on Mahayana religious thoughts. Artistic work of Kabul and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni Buddhist Temples are different from the point of artistic style and material applied; Bagram Artistic works are made in style of Garico Accepted: 19.09.2019 Buddhic and Garico Kushan but Tapa Narenj Hill artistic works are made based on Buddhist regulation and are seen as ethnical and Hellenistic style. There are similarities among Bagram Published: 01.10.2019 and Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghani Buddhist Temples but most differentiates are set on statues in which Tapa Sardar Hill of Ghazni statue is lied in which is different from sit and stand still statues of Bagram. -

Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, and FUTURE by Andrew Watkins

PEACEWORKS Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, AND FUTURE By Andrew Watkins NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the phenomenon of insurgent fragmentation within Afghanistan’s Tali- ban and implications for the Afghan peace process. This study, which the author undertook PEACE PROCESSES as an independent researcher supported by the Asia Center at the US Institute of Peace, is based on a survey of the academic literature on insurgency, civil war, and negotiated peace, as well as on interviews the author conducted in Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Andrew Watkins has worked in more than ten provinces of Afghanistan, most recently as a political affairs officer with the United Nations. He has also worked as an indepen- dent researcher, a conflict analyst and adviser to the humanitarian community, and a liaison based with Afghan security forces. Cover photo: A soldier walks among a group of alleged Taliban fighters at a National Directorate of Security facility in Faizabad in September 2019. The status of prisoners will be a critical issue in future negotiations with the Taliban. (Photo by Jim Huylebroek/New York Times) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Environmental Problems of the Marine and Coastal Area of Pakistan: National Report

-Ç L^ q- UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Environmental problems of the marine and coastal area of Pakistan: National Report UNEP Regional Seal Reports and Studies No. 77 PREFACE The Regional Seas Pragra~eMS initiated by UMEP in 1974. Since then the Governing Council of UNEP has repeatedly endorsed a regional approach to the control of marine pollution and the ma-t of marine ad coastal resources ad has requested the develqmmt of re#ioml action plans. The Regional Seas Progr- at present includes ten mimyand has over 120 coastal States à participating in it. It is amceival as an action-oriented pmgr- havim cmcera not only fw the consqmces bt also for the causes of tnvirommtal dtgradation and -ssing a msiveapproach to cantrollbg envimtal -1- thmqb the mamgaent of mrine and coastal areas. Each regional action plan is formulated according to the needs of the region as perceived by the Govemnents concerned. It is designed to link assessment of the quality of the marine enviroment and the causes of its deterioration with activities for the ma-t and development of the marine and coastal enviroment. The action plans promote the parallel developmmt of regional legal agreemnts and of actioworimted pmgr- activitiesg- In Hay 1982 the UNEP Governing Council adopted decision 10/20 requesting the Executive Director of UNEP "to enter into consultations with the concerned States of the South Asia Co-operative Envirof~entProgran~e (SACEP) to ascertain their views regarding the conduct of a regional seas programe in the South Asian Seasm. In response to that request the Executive Director appointed a high level consultant to undertake a mission to the coastal States of SACW in October/November 1982 and February 1983. -

Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central

MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2012 MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), within the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and in Pakistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions that shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the customs offices of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the World Customs Office, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Natascha Eichinger (Consultant) Platon Nozadze (Consultant) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Shaukat Ullah Khan (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) A. -

“TELLING the STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: a Regional Perspective (2011-2016)

“TELLING THE STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective (2011-2016) Emma Hooper (ed.) This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. © 2016 CIDOB This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel.: 933 026 495 www.cidob.org [email protected] D.L.: B 17561 - 2016 Barcelona, September 2016 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES 5 FOREWORD 11 Tine Mørch Smith INTRODUCTION 13 Emma Hooper CHAPTER ONE: MAPPING THE SOURCES OF TENSION WITH REGIONAL DIMENSIONS 17 Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective .......... 19 Zahid Hussain Mapping the Sources of Tension and the Interests of Regional Powers in Afghanistan and Pakistan ............................................................................................. 35 Emma Hooper & Juan Garrigues CHAPTER TWO: KEY PHENOMENA: THE TALIBAN, REFUGEES , & THE BRAIN DRAIN, GOVERNANCE 57 THE TALIBAN Preamble: Third Party Roles and Insurgencies in South Asia ............................... 61 Moeed Yusuf The Pakistan Taliban Movement: An Appraisal ......................................................... 65 Michael Semple The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan ....................................................................... -

Cultural Heritage Vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond

Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond Cheryl Benard Eli Sugarman Holly Rehm CONFERENCE REPORT December 2012 Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond June 4-5, 2012 SAIS, Johns Hopkins University Washington, D.C. 20036 sponsored by Ludus and ARCH Virginia Conference Report Cheryl Benard Eli Sugarman Holly Rehm © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodav. 2, Stockholm-Nacka 13130, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond” is a Conference Report published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. -

November 1, 2015

Page 4 November 1, 2015 (1) Jihadi Council ... claimed a quarter of a million lives war,” he noted. Haji Ata Jan Haqbayan, head of the University part of the Aga Khan De- to express his gratitude to the Afghan and triggered an exodus of refugees He called Taliban “the servants and provincial council of Zabul province, velopment Network and the French government in recognizing the achieve- they wanted to determine the fate to Europe. wagers of Pakistan.” said no compensation has been given NGO, La Chaîne de l’Espoir. (PR) ments of the journalists. of the already agreed post of Prime Top diplomats from 17 countries, as Pakistan has long been accused of to the kidnappers in return. Hundreds of Taliban militants, security Minister. (10) Bahrain Reviews ... well as the United Nations and the backing insurgent groups in Afghan- We still demand central government personnel and 163 civilians were killed The council, which constitutes ex- European Union, gathered for the istan. to arrest the illegal armed group be- edition of the Manama Dialogue. In during the war for the control of Kun- Jihadists and political leaders, urged talks bringing together all the main Despite President Ashraf Ghani’s hind it and punish them, Haqbayan the meeting, they discussed the ef- duz city and hundreds others sustained the government to take their call se- outside players in the four-year-old almost nine-month efforts to bring said. forts exerted for security and peace injuries, according to officials. (Xinhua) rious for convening the traditional crisis for the first time. the two states closer, the relations Including women and children, the in Yemen. -

Khushal Khan Khattak's Educational Philosophy

Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy Presented to: Department of Social Sciences Qurtuba University, Peshawar Campus Hayatabad, Peshawar In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Of Doctor of Philosophy in Education By Niaz Muhammad PhD Education, Research Scholar 2009 Qurtuba University of Science and Information Technology NWFP (Peshawar, Pakistan) In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. ii Copyrights Niaz Muhammad, 2009 No Part of this Document may be reprinted or re-produced in any means, with out prior permission in writing from the author of this document. iii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL DOCTORAL DISSERTATION This is to certify that the Doctoral Dissertation of Mr.Niaz Muhammad Entitled: Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy has been examined and approved for the requirement of Doctor of Philosophy degree in Education (Supervisor & Dean of the Social Science) Signature…………………………………. Qurtuba University, Peshawar Prof. Dr.Muhammad Saleem (Co-Supervisor) Signature…………………………………. Center of Pashto Language & Literature, Prof. Dr. Parvaiz Mahjur University of Peshawar. Examiners: 1. Prof. Dr. Saeed Anwar Signature…………………………………. Chairman Department of Education Hazara University, External examiner, (Pakistan based) 2. Name. …………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) 3. Name. ………………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) iv ABSTRACT Khushal Khan Khattak passed away about three hundred and fifty years ago (1613–1688). He was a genius, a linguist, a man of foresight, a man of faith in Al- Mighty God, a man of peace and unity, a man of justice and equality, a man of love and humanity, and a man of wisdom and knowledge. He was a multidimensional person known to the world as moralist, a wise chieftain, a great religious scholar, a thinker and an ideal leader of the Pushtoons. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Tabai Dam (Khyber District) Sep, 2018

Initial Environmental Examination Report ________________________________________ Project Number: 47021-002 Loan Number: 3239 PAK: Federally Administered Tribal Areas Water Resources Development Project Initial Environmental Examination Report for Tabai Small Dam, District Khyber Prepared by Project Management Unit, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan For the Asian Development Bank Date received by ADB: Jan 2020 NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report “$” refer to US dollars. This initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project Management Unit PMU FATA Water Resources Development Project FWRDP Merged Areas Secretariat FEDERALLY ADMINISTERED TRIBAL AREAS WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT PROJECT INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION (IEE) TABAI DAM (KHYBER DISTRICT) SEP, 2018 FATA WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT PROJECT CONSULTANTS House # 3, Street # 1, Near Board Bazar, Tajabad, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Tel: +92 91 5601635 - 6 Fax: +92 91 5840807 E-mail: [email protected]