International Association for Intercultural Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sign of Peace the Mass in Slow Motion

The Mass In Slow Motion Volume 22 The Sign of Peace The Mass In Slow Motion is a series on the Mass explaining the meaning and history of what we do each Sunday. This series of flyers is an attempt to add insight and understanding to our celebration of the Sacred Liturgy. This series will follow the Mass in order beginning with The Gathering Rite through The Final Blessing and Dismissal, approximately 25 volumes. Previous editions are available via the rectory office or our website: www.hcscchurch.org. The Rite of Peace follows the “Our Father” and the prayer “Lord Jesus Christ you said to your Apostles, „I leave you peace…‟, by which the Church asks for peace and unity for herself and for the whole human family, and the faithful express to each other their ecclesial communion and mutual charity before communicating in the Sacrament. The manner of expressing this sign of peace is established by Conferences of Bishops in accordance with the culture and customs of the peoples. It is, however, appropriate that each person offer the sign of peace only to those who are nearest and in a sober manner. (cf G.I.R.M. # 82) Other instructions in the Missal indicate that exchange of peace is shared “if appropriate” and that the celebrant “gives the sign of peace to a deacon or minister.” The instruction adds that the priest may give the sign of peace to the ministers but always remains within the sanctuary, so as not to disturb the celebration. Hence, we learn some of the following things about the sign of peace: 1. -

The Meanings of the Term Mudra and a Historical Outline of "Hand

The Meanings of the term Mudra T h e M and a Historical Outline of ae n ni "Hand gestures" g s o f ht e Dale Todaro t re m M u d 梗 概 ar a この 拙 論 は2部 に分 か れ る。 n d 第1部 は"mudra"と い う語 の最 も一 般 的 な 定 義 を 扱 う。仏 教 ・ヒ ン ドゥー 教 a H を 研 究 して い る学 者 や東 洋 の 図像 学 の専 門 家 は、 大 抵、"皿udra"の さ ま ざ まな 意 i torical Outline味 を 知 って い る。 しか し、特 に タ ン トラ にお い て 使 用 され た"mudr翫"の す べ て の 定 義 が、 どん な 参考 文 献 に も見 つ か るわ け で は な い。 従 って、 第1部 は これ ら 種 々の、 一 般 的 な"mudra"の 語 法 を集 め る よ う試 み た。 又、 イ ン ドの舞 踏 や 劇 につ いて 書 いた 人 が、"hasta"と い う語 を 使 用 す べ きで あ るの に、 専 門的 に言 え ば 誤 って"mudra"を 用 いて い る。 それ に つ いて も説 明 を試 み た。 fo " 第1部 よ りも長 い 第2部 で は、"印 契(手 印)"と い う意 味 で使 用 され た"mu- H a dra"の 歴 史 の あ らま しを、 系 統 的 に述 べ た。 印契 の歴 史 上 異 な った 使 用 と意 味 n d g は、 次 の4に お い て 顕著 にみ られ る。 即 ち、1)ヴ ェー ダ の儀 礼、2)規 格 化 され た se ut イ ン ドの舞 踏、3)イ ン ドの彫 刻(仏 教、 ヒ ン ド ゥー 教、 ジ ャイ ナ教)、4)タ ン ト r s"e ラの 成 就 法、 で あ る。 これ ら4の 分 野 は す べ て、 共 通 して、 イ ン ドで 使 用 され た 印 契 の 伝統 か ら由 来 して い る。 そ しで、 い くつか の事 例 に お いて、 イ ン ドか ら 日 本 密 教 の 伝 統 まで に わ た って、 特 定 の"mudra"が 驚 くほ ど継 続 して 使 用 され て い るこ とが、 証 明 で き る。 Introduction The goal of this short essay is twofold. -

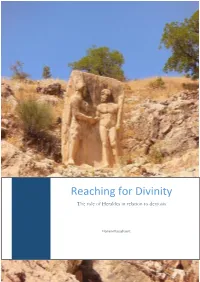

Reaching for Divinity the Role of Herakles in Relation to Dexiosis

Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht University RMA ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES thesis under the supervision of dr. R. Strootman | prof. L.V. Rutgers Cover Photo: Dexiosis relief of Antiochos I of Kommagene with Herakles at Arsameia on the Nymphaion. Photograph by Stefano Caneva, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. 1 Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht 2017 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this master thesis would not have been possible were not it for the advice, input and support of several individuals. First of all, I owe a lot of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Rolf Strootman, whose lectures not only inspired the subject for this thesis, but whose door was always open in case I needed advice or felt the need to discuss complex topics. With his incredible amount of knowledge on the Hellenistic Period provided me with valuable insights, yet always encouraged me to follow my own view on things. Over the course of this study, there were several people along the way who helped immensely by providing information, even if it was not yet published. Firstly, Prof. Dr. Miguel John Versluys, who was kind enough to send his forthcoming book on Nemrud Dagh, an important contribution to the information on Antiochos I of Kommagene. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Iossif who even managed to send several articles in the nick of time to help my thesis. Lastly, the National Numismatic Collection department of the Nederlandse Bank, to whom I own gratitude for sending several scans of Hellenistic coins. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

Scout Uniform, Scout Sign, Salute and Handshake

In this Topic: Participation Promise and Law Scout Uniform, Scout Salute and Scout Handshake Scouts and Flags Scouting History Discussion with the Scout Leader Introducing Tenderfoot Level The Journey Life in the Troop is a journey. As in any journey one embarks on, there needs to be proper preparation for the adventure ahead. This is important so as to steer clear of obstacles and perils, which, with good foresight, can often be avoided. As Scouts we follow our simple motto: Be Prepared! With this in mind you can start your preparations for the journey ahead… The Tenderfoot This level offers a starting point for a new member in the troop. For those Cubs whose time has come to move up from the pack, the Tenderfoot level is a stepping stone linking the pack with the troop. For those scouts who have joined from outside the group, this will be the beginning of their scouting life. How do I achieve this level? The five sections in this level can be done in any order. If you are a Cub Scout moving up from the pack, you will have already started the Cub Scout link badge. The Tenderfoot level is started at the same time. As you can see some of the requirements are the same for both awards. If you have just joined the scouting movement as part of the troop, this level will provide you with all the basic information to help you learn what scouting is all about. Look at the sheet on the next page so that you are able to keep track of your progress. -

Hand Gestures

L2/16-308 More hand gestures To: UTC From: Peter Edberg, Emoji Subcommittee Date: 2016-10-31 Proposed characters Tier 1: Two often-requested signs (ILY, Shaka, ILY), and three to complete the finger-counting sets for 1-3 (North American and European system). None of these are known to have offensive connotations. HAND SIGN SHAKA ● Shaka sign ● ASL sign for letter ‘Y’ ● Can signify “Aloha spirit”, surfing, “hang loose” ● On Emojipedia top requests list, but requests have dropped off ● 90°-rotated version of CALL ME HAND, but EmojiXpress has received requests for SHAKA specifically, noting that CALL ME HAND does not fulfill need HAND SIGN ILY ● ASL sign for “I love you” (combines signs for I, L, Y), has moved into mainstream use ● On Emojipedia top requests list HAND WITH THUMB AND INDEX FINGER EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 2, European style ● ASL sign for letter ‘L’ ● Sign for “loser” ● In Montenegro, sign for the Liberal party ● In Philippines, sign used by supporters of Corazon Aquino ● See Wikipedia entry HAND WITH THUMB AND FIRST TWO FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, European style ● UAE: Win, victory, love = work ethic, success, love of nation (see separate proposal L2/16-071, which is the source of the information below about this gesture, and also the source of the images at left) ● Representation for Ctrl-Alt-Del on Windows systems ● Serbian “три прста” (tri prsta), symbol of Serbian identity ● Germanic “Schwurhand”, sign for swearing an oath ● Indication in sports of successful 3-point shot (basketball), 3 successive goals (soccer), etc. HAND WITH FIRST THREE FINGERS EXTENDED ● Finger-counting 3, North American style ● ASL sign for letter ‘W’ ● Scout sign (Boy/Girl Scouts) is similar, has fingers together Tier 2: Complete the finger-counting sets for 4-5, plus some less-requested hand signs. -

Pointing Gesture in Young Children Hand Preference and Language Development

Pointing gesture in young children Hand preference and language development Hélène Cochet and Jacques Vauclair Aix-Marseille University This paper provides an overview of recent studies that have investigated the development of pointing behaviors in infants and toddlers. First, we focus on deictic gestures and their role in language development, taking into account the different hand shapes and the different functions of pointing, and examining the cognitive abilities that may or may not be associated with the production of pointing gestures. Second, we try to demonstrate that when a distinction is made between pointing gestures and manipulative activities, the study of children’s hand preference can help to highlight the development of speech-gesture links. Keywords: toddlers, gestural communication, pointing, handedness, speech- gesture system Emergence of communicative gestures: Focus on pointing gestures Pointing is a specialized gesture for indicating an object, event or location. Chil- dren start using pointing gestures at around 11 months of age (Butterworth & Morissette, 1996; Camaioni, Perucchini, Bellagamba, & Colonnesi, 2004), and this behavior opens the door to the development of intentional communication. One of the prerequisites for the production of pointing gestures is a shared experi- ence between the signaler and the recipient of the gesture, that is, a simultaneous engagement with the same external referent, usually referred to as joint attention (e.g., Carpenter, Nagell, & Tomasello, 1998). While pointing is sometimes regard- ed as a “private gesture” (Delgado, Gómez, & Sarriá, 2009), whose main role is to regulate the infant’s attention rather than to enable the latter to communicate with a recipient, a growing body of research suggests that the onset of pointing gestures reflects a newly acquired ability to actively direct the adult’s attention to outside entities in triadic interactions (e.g., Liszkowski, 2005; Tomasello, Carpenter, & Liszkowski, 2007). -

16 Gestures by 16 Months

16 Gestures by 16 Months Children Should Learn at Least 16 Gestures by 16 Months Good communication development starts in the first year of life and goes far beyond learning how to talk. Communication development has its roots in social interaction with parents and other caregivers during everyday activities. Your child’s growth in social communication is important because it helps your child connect with you, learn language and play concepts, and sets the stage for learning to read and future success in school. Good com- munication skills are the best tool to prevent behavior problems and make it easier to work through moments of frustration that all infants and toddlers face. Earlier is Better Catching communication and language difficulties By observing children’s early early can prevent potential problems later with gestures, you can obtain a critical behavior, learning, reading, and social interaction. snapshot of their communication Research on brain development reminds us that “earlier IS better” when teaching young children. development. Even small lags in The most critical period for learning is during the communication milestones can first three years of a child’s life. Pathways in the add up and impact a child’s rate brain develop as infants and young children learn of learning that is difficult to from exploring and interacting with people and objects in their environment. The brain’s architec- change later. Research with young ture is developing the most rapidly during this crit- children indicates that the development of gestures from 9 to 16 ical period and is the most sensitive to experiential months predicts language ability 2 years later, which is significant learning. -

University of Groningen a Cultural History of Gesture Bremmer, JN

University of Groningen A Cultural History Of Gesture Bremmer, J.N.; Roodenburg, H. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1991 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N., & Roodenburg, H. (1991). A Cultural History Of Gesture. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 02-10-2021 The 'hand of friendship': shaking hands and other gestures in the Dutch Republic HERMAN ROODENBURG 'I think I can see the precise and distinguishing marks of national characters more in those nonsensical minutiae than in the most important matters of state'. -

Namaste: the Significance of a Yogic Greeting

Newsletter Archives Namaste: The Significance of a Yogic Greeting The material contained in this newsletter/article is owned by ExoticIndiaArt Pvt Ltd. Reproduction of any part of the contents of this document, by any means, needs the prior permission of the owners. Copyright C 2000, ExoticIndiaArt Namaste: The Significance of a Yogic Greeting Article of the Month - November 2001 In a well-known episode it so transpired that the great lover god Krishna made away with the clothes of unmarried maidens, fourteen to seventeen years of age, bathing in the river Yamuna. Their fervent entreaties to him proved of no avail. It was only after they performed before him the eternal gesture of namaste was he satisfied, and agreed to hand back their garments so that they could recover their modesty. The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and lightly bowing the head. In the simplest of terms it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. Namaste is a composite of the two Sanskrit words, nama, and te. Te means you, and nama has the following connotations: To bend To bow To sink To incline To stoop All these suggestions point to a sense of submitting oneself to another, with complete humility. Significantly the word 'nama' has parallels in other ancient languages also. It is cognate with the Greek nemo, nemos and nosmos; to the Latin nemus, the Old Saxon niman, and the German neman and nehman. All these expressions have the general sense of obeisance, homage and veneration. -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents