Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd in Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yokes and Chains

Yokes and Chains: Introduction to discussion materials This DVD consists of footage that has been taken over the last 3 years of the Lifeline Expedition journeys. It is divided up into 3 chapters –You will find below for each chapter: words and phrases that students can research the meaning of, discussion questions for class and research tasks. There is also a worksheet for each chapter which allows students to select appropriate words to fill in quotes from the chapter. We suggest that these worksheets should not be given at the first showing as students may then only listen to fill in the missing gaps rather than following the flow of the chapter. Most students should be able to fill in the gaps from the selected word choices without seeing the chapter a second time. Extra information about the Lifeline Expedition can be found at www.lifelineexpedition.co.uk and also at www.lifelineexpedition.co.uk/mota. Google searches on “Lifeline Expedition”, “March of the Abolitionists” or “Reconciliation marches yokes and chains” will all reveal more about the initiative and how it has been perceived by the media. At the end of this material we have added selections from a book called “The Heart of Racial Justice” and “The Four Healing Steps” mentioned in chapter one which provides further useful points for discussion. Our focus is very much on the legacies of the Atlantic slave trade. This complements other excellent material on the history of the slave trade and also about contemporary slavery today. We highly recommend the educational resource pack entitled “Ending Slavery” which can be downloaded at: http://youth.cms-uk.org/FreeForAll/Resources/EndingSlavery/tabid/134/Default.aspx ©Global Net Productions & Lifeline Expedition • [email protected] 1 www.yokesandchains.com www.globalnetproductions.com www.lifelineexpedition.co.uk Yokes and Chains: Chapter 1 This part of the DVD starts with short selections from the entire DVD followed by an overview of what took place in the Atlantic slave trade and the impact the slave trade has on society today. -

Ethnic Diversity in Politics and Public Life

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 01156, 22 October 2020 By Elise Uberoi and Ethnic diversity in politics Rebecca Lees and public life Contents: 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 2. Parliament 3. The Government and Cabinet 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 5. Public sector organisations www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Ethnic diversity in politics and public life Contents Summary 3 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 6 1.1 Categorising ethnicity 6 1.2 The population of the United Kingdom 7 2. Parliament 8 2.1 The House of Commons 8 Since the 1980s 9 Ethnic minority women in the House of Commons 13 2.2 The House of Lords 14 2.3 International comparisons 16 3. The Government and Cabinet 17 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 19 4.1 Devolved legislatures 19 4.2 Local government and the Greater London Authority 19 5. Public sector organisations 21 5.1 Armed forces 21 5.2 Civil Service 23 5.3 National Health Service 24 5.4 Police 26 5.4 Justice 27 5.5 Prison officers 28 5.6 Teachers 29 5.7 Fire and Rescue Service 30 5.8 Social workers 31 5.9 Ministerial and public appointments 33 Annex 1: Standard ethnic classifications used in the UK 34 Cover page image copyright UK Youth Parliament 2015 by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped 3 Commons Library Briefing, 22 October 2020 Summary This report focuses on the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in a range of public positions across the UK. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950- 2010 Alhargan, Haya Saleh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 1 ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950-2010 by Haya Saleh AlHargan Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Middle East and Mediterranean Studies Programme King’s College University of London 2015 2 ABSTRACT This study investigates Anglo-Saudi cultural relations from 1950 to 2010, with the aim of greater understanding the nature of those relations, analysing the factors affecting them and examining their role in enhancing cultural relations between the two countries. -

Race, Ethnicity & Equality in UK History

Race, Ethnicity & Equality in UK History: A Report and Resource for Change ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OCTOBER 2018 Hannah Atkinson, Suzanne Bardgett, Adam Budd, Margot Finn, Christopher Kissane, Sadiah Qureshi, Jonathan Saha, John Siblon and Sujit Sivasundaram © The Royal Historical Society 2018. All rights reserved. University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT 020 7387 7532 Race, Ethnicity & Equality in UK History: A Report and Resource for Change ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OCTOBER 2018 Attendeees at the January 2018 RHS Public History Prize award ceremony, including Dr Sadiah Qureshi (an author of this report) and Kavita Puri (whose Partititon Voices won both the Radio & Podcasts category and the overall prize). 4 | Race, Ethnicity & Equality in UK History: A Report and Resource for Change Contents | 5 Contents Executive Summary 7 Foreword 11 Abbreviations 15 Key Terms 16 1. Introduction 21 2 History in Context 29 3. RHS Survey 47 4. Recommendations and Advice 73 5. RHS Roadmap for Change 95 RHS Race, Ethnicity and Equality Group 98 Acknowledgements 100 Appendix I: Further Reading & Online Resources 101 Appendix II: School Focus Group Questions 121 Contents | 5 “The worst is being the only BME member of staff in a department. Whenever I tried to discuss it with my colleagues (all of whom were non-BME), I was told unequivocally that I was imagining it.” RHS SURVEY RESPONDENT, 2018 6 | Race, Ethnicity & Equality in UK History: A Report and Resource for Change Executive Summary | 7 Executive Summary Recent research in Black history, histories of migration and ethnicity, and histories of race, imperialism and decolonisation has transformed our knowledge and understanding of the British, European and global past. -

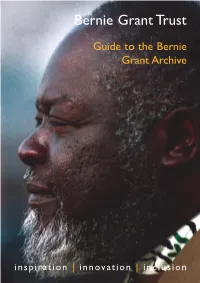

Guide to the Archive

Bernie Grant Trust Guide to the Bernie Grant Archive inspiration | innovation | inclusion Contents Compiled by Dr Lola Young OBE Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion . 4 Edited by Machel Bogues What’s in the Bernie Grant Archive? . 11 How it’s organised . 14 Index entries . 15 Tributes - 2000 . 16 What are Archives? . 17 Looking in the Archives . 17 Why Archives are Important . 18 What is the Value of the Bernie Grant Archive? . 18 How we set up the Bernie Grant Collection . 20 Thank you . 21 Related resources . 22 Useful terms . 24 About The Bernie Grant Trust . 26 Contacting the Bernie Grant Archive . 28 page | 3 Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion Born into a family of educationalists on London. The 4000 and overseas. He was 17 February 1944 in n 18 April 2000 people who attended a committed anti-racist Georgetown, Guyana, thousands of O the service at Alexandra activist who campaigned Bernie Grant was the people lined the streets Palace made this one of against apartheid South second of five children. of Haringey to follow the largest ever public Africa, against the A popular, sociable child the last journey of a tributes at a funeral of a victimisation of black at primary school, he charismatic political black person in Britain. people by the police won a scholarship to leader. Bernie Grant had in Britain and against St Stanislaus College, a been the Labour leader Bernie Grant gained racism in health services Jesuit boys’ secondary of Haringey Council a reputation for being and other public and school. Although he during the politically controversial because private institutions. -

The Negritude Movements in Colombia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses October 2018 THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA Carlos Valderrama University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Folklore Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Valderrama, Carlos, "THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1408. https://doi.org/10.7275/11944316.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1408 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2018 Sociology © Copyright by Carlos Alberto Valderrama Rentería 2018 All Rights Reserved THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Approved as to style and content by __________________________________________ Agustin Laó-Móntes, Chair __________________________________________ Enobong Hannah Branch, Member __________________________________________ Millie Thayer, Member _________________________________ John Bracey Jr., outside Member ______________________________ Anthony Paik, Department Head Department of Sociology DEDICATION To my wife, son (R.I.P), mother and siblings ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have finished this dissertation without the guidance and help of so many people. My mentor and friend Agustin Lao Montes. My beloved committee members, Millie Thayer, Enobong Hannah Branch and John Bracey. -

Afro-Colombians from Slavery to Displacement

A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AND EXCLUSION: AFRO-COLOMBIANS FROM SLAVERY TO DISPLACEMENT A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Sascha Carolina Herrera, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. October 31, 2012 A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AND EXCLUSION: AFRO-COLOMBIANS FROM SLAVERY TO DISPLACEMENT Sascha Carolina Herrera, B.A. MALS Mentor: Kevin Healy, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In Colombia, the Afro-Colombian population has been historically excluded and marginalized primarily due to the legacy of slavery deeply embedded within contemporary social and economic structures. These structures have been perpetuated over many generations of Afro-Colombians, who as a result have been caught in a recurring cycle of poverty throughout their history in Colombia. In contemporary Colombia, this socio-economic situation has been exacerbated by the devastating effects of various other economic and social factors that have affected the Colombian society over half century and a prolonged conflict with extensive violence involving the Colombian state, Paramilitaries, and Guerrillas and resulting from the dynamics of the war on drugs and drug-trafficking in Colombian society. In addition to the above mentioned factors, Afro-Colombians face other types of violence, and further socio-economic exclusion and marginalization resulting from the prevailing official development strategies and U.S. backed counter-insurgency and counter-narcotics strategies and programs of the Colombian state. ii Colombia’s neo-liberal economic policies promoting a “free” open market approach involve the rapid expansion of foreign investment for economic development, exploitation of natural resources, and the spread of agro bio-fuel production such as African Palm, have impacted negatively the Afro-Colombian population of the Pacific coastal region. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: an Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques

Part I Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: An Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques Translated from the Portuguese by Richard Wall "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho INTRODUCTION t the beginning of the nineteenth century, Thomas Clarkson por- Atrayed the anti-slavery movement as a river of ideas that had swollen over time until it became an irrepressible torrent. Clarkson had no doubt that it had been the thought and action of all of those who, like Raynal, Benezet, and Wilberforce, had advocated “the cause of the injured Afri- cans” in Europe and in North America, which had ultimately lead to the abolition of the British slave trade, one of the first steps toward abolition of slavery itself.1 In our times, there are several views on what led to abolition and they all differ substantially from the river of ideas imagined by Clarkson. Iron- ically, for one of those views, it is as if Clarkson’s river had reversed its course and started to flow from its mouth to its source. Anyone who, for example, opens the UNESCO web page (the Slave Route project) will have access to an eloquent example of that approach, so radically opposed to Clarkson’s. In effect, one may read there that, “the first fighters for the abolition -

Through the Wire: Black British People and the Riot

Nka THROUGH THE WIRE Black British People and the Riot o one knows why riots occur. Or, perhaps Eddie Chambers more accurately, no one knows when the N precise confluence of factors will occur to spark a riot. After all, almost as a matter of rou- tine, Black people have endured regular, almost mundane, violence and discrimination, both at the hands of society and the police. And yet riots involving Black people protesting against such violence are sporadic, rather than regular, events. Here I explore some of the ways in which press photographs have visualized key episodes of rioting involving Black people in the English cities of Lon- don and Birmingham. These range from the Not- ting Hill riots of 1958 through the riots that took place in Birmingham, Brixton, and Tottenham in 1985. Th s text considers four wire photographs from the Baltimore Sun’s historical photo archive. Wire photos differed from traditional photographic prints insofar as the wire print resulted from breakthrough technology that allowed a photographic image to be scanned, transmitted over “the wire” (telegraph, phone, satellite networks), and printed at the receiv- ing location. Opening here with a press photograph Journal of Contemporary African Art • 36 • May 2015 6 • Nka DOI 10.1215/10757163-2914273 © 2015 by Nka Publications Published by Duke University Press Nka A youth carries a firebomb on the second day of the Handsworth riots in Birmingham. © Press Association Images Chambers Nka • 7 Published by Duke University Press Nka of a group of Black youth overturning a large police of violence and conquest is being played out. -

The Slave Route � La Ruta Del Esclavo

La route de l’esclave G The Slave Route G La Ruta del Esclavo NEWSLETTER No. 1 - September 2000 EDITORIAL S history’s first system of globalization, the transatlantic Aslave trade and the slavery born of that trade constitute the invisible substance of relations between Europe, Africa, the Americas and the West Indies. In view of its human cost (tens of millions of victims), the ideology that subtended it (the intellectual construction of cultural contempt for Africans, and hence the racism that served to justify the buying and selling of human beings as, according to the definition of the French Code Noir, “chattel”), and the sheer scale of the economic, social and cultural destructuring of the African continent, that dramatic episode in the history of humanity demands that we re-examine the reasons for the historical silence in which it has for so long been swathed. In this matter it is vital to respond to the claim voiced by Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel Revolt and rebellion: that “the executioner always kills twice, the second time through the other side of the slave trade and slavery. silence”. Collection UNESCO: The Slave Route Hence, the issues at stake in the Slave Route project are essentially: Historical truth, peace, development, human rights, Contents: memory, intercultural dialogue. Background and objectives The challenge that this project, whose approach is resolutely of the project 2 scientific, has set the international community is to link the Structure 2 historical truth concerning a tragedy that has been wilfully masked Institutional meetings 3 to the concern to illuminate the intercultural dialogue born of the Activities and special events 3 enforced encounter between millions of Africans, Amerindians and Europeans in the Americas and West Indies, as well as in those Financing 6 overlooked areas of slavery, the Mediterranean and the Indian Cooperation with the media 6 Ocean. -

A Resource Book for Managers of Sites and Itineraries of Memory a UNESCO Endeavor the Slave Route: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage

A Resource book for Managers of Sites and Itineraries of Memory A UNESCO Endeavor The Slave Route: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage 2018 At the suggestion of Haiti and the African countries, UNESCO launched the Slave Route Project in September 1994 in Ouida, Benin, to break the silence on the subject of human trafficking from Africa, slavery and its abolition in various regions of the world. The main objective of the project is to contribute to a better understanding of the deep-seated causes of slavery, its forms of operation, its consequences on modern societies, in particular the global transformations and cultural interactions among peoples affected by this tragedy. The Project was implemented through five immediate objectives: research, development of pedagogical tools, preservation of documents and oral traditions, promotion of living cultures and the diverse contributions of African diaspora and promotion of sites and itineraries of memory. The Slave Route Project: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage have contributed to the acknowledgement of the slave trade and slavery as ‘crimes against humanity’ – World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, Durban (South Africa, 2001) – and the proclamation of the International Decade for people of African descent (2015-2024) on the theme of “Recognition, Justice and Development”, by the UN General Assembly. The UNESCO’s Slave Route Project encourages States not only to identify, asses, restore, preserve and promote their memorial sites and itineraries, but also to identify the heritage sites considered to be of Outstanding Universal Value. In recent decades, several needs have emerged that require a broadening of the fields of study, a new dynamic of memory spaces, concrete and precise answers in the fields of historical research and heritage conservation.