Mapping of Race and Poverty in Birmingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

33 Birmingham

33 Birmingham - Pheasey via Perry Barr Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Carrs Lane (Stop BS16) 0500 0540 0600 0617 0633 0650 0700 0710 0720 0730 0740 0750 0800 0810 0820 0830 Newtown, Six Ways Aston (near) 0510 0550 0610 0627 0644 0701 0711 0721 0731 0742 0752 0802 0812 0822 0832 0842 Aldridge Road (Stop T2) 0434 0514 0529 0554 0614 0631 0648 0706 0716 0726 0736 0747 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 Birmingham City University, Wellhead Lane 0436 0516 0531 0556 0616 0633 0650 0708 0718 0728 0738 0749 0759 0809 0819 0829 0839 0849 Warren Farm, Chingford Road (before) 0442 0522 0537 0602 0622 0639 0656 0715 0725 0735 0746 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 0857 Kingstanding, Kingstanding Police Station 0448 0528 0543 0608 0628 0645 0702 0722 0732 0742 0754 0805 0815 0825 0835 0845 0855 0905 (before) Collingwood Centre (adjacent) 0453 0533 0548 0613 0633 0650 0707 0727 0737 0747 0800 0811 0821 0831 0841 0851 0901 0911 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Carrs Lane (Stop BS16) 0840 0850 0900 0910 0920 0930 0940 0950 1000 1010 1020 1030 1040 1050 1100 1110 1120 1130 Newtown, Six Ways Aston (near) 0852 0902 0912 0922 0932 0942 0952 1002 1012 1022 1032 1042 1052 1102 1112 1122 1132 1142 Aldridge Road (Stop T2) 0858 0908 0918 0928 0938 0948 0958 1008 1018 1028 1038 1048 1058 1108 1118 1128 1138 1148 Birmingham City University, Wellhead Lane 0900 0910 0920 0930 0940 0950 1000 1010 1020 1030 1040 1050 1100 1110 1120 1130 1140 -

Land for Sale

LAND FOR SALE Land to the rear of 359 Lickey Road, Rednal, B45 8UR • Located in a popular residential area • Close to many amenities • Site area: 2.55 acres (1.034 hectares) LOCATION The site is situated just on the outskirts of Rednal, being easily accessed from Longbridge, Rubery and Barnt Green. The site is 0.6 miles south of Rednal town centre, 1.7 miles south west of Longbridge and 9.2 miles south of Birmingham City Centre. The site is located to the rear if the residential properties on Lickey Road, this road joins the A38, one of the major A roads in England. The site is positioned 1.4 miles from Longbridge Station, 1.9 miles from Morrisons and 0.3 miles from The Oak Tree Public House. The nearest bus stop is on Lickey Road opposite Leach Green Lane and the site is 0.1 miles from the nearest post box. The nearest schools are Rednal Hill Infant School (0.5 miles), St Columbas Catholic Primary School (0.9 miles) and Colmers School and Sixth Form College (1.4 miles). SITE DESCRIPTION The Property comprises a triangular green field. The total site extends to 2.55 acres (1.034 hectares) and comprises vacant land. The site has a single access from Lickey Road. The site falls within a 40 mph zone. The site gently slopes down to the edge of Cofton Park. PLANNING The site is located within Birmingham City Council for planning purposes and the most up to date policy is the Pre-Submission Birmingham Development Plan 2031 defining this former nursery as Open Space. -

Things to Do and Places to Go Sept 2020

Things To Do And Places to Go! September 2020 Table of Contents Parks and Nature Reserves ............................................................................................... 3 Arrow Valley Country Park ....................................................................................................... 3 Clent Hills ................................................................................................................................ 3 Cofton Park .............................................................................................................................. 3 Cannon Hill Park ...................................................................................................................... 3 Highbury Park .......................................................................................................................... 3 King’s Heath Park ..................................................................................................................... 4 Lickey Hills ............................................................................................................................... 4 Manor Farm ............................................................................................................................. 4 Martineau Gardens .................................................................................................................. 4 Morton Stanley Park ............................................................................................................... -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

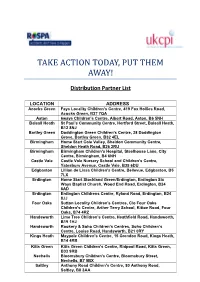

Take Action Today, Put Them Away!

TAKE ACTION TODAY, PUT THEM AWAY! Distribution Partner List LOCATION ADDRESS Acocks Green Fays Locality Children’s Centre, 419 Fox Hollies Road, Acocks Green, B27 7QA Aston 6ways Children’s Centre, Albert Road, Aston, B6 5NH Balsall Heath St Paul’s Community Centre, Hertford Street, Balsall Heath, B12 8NJ Bartley Green Doddington Green Children's Centre, 28 Doddington Grove, Bartley Green, B32 4EL Birmingham Home Start Cole Valley, Sheldon Community Centre, Sheldon Heath Road, B26 2RU Birmingham Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Steelhouse Lane, City Centre, Birmingham, B4 6NH Castle Vale Castle Vale Nursery School and Children’s Centre, Yatesbury Avenue, Castle Vale, B35 6DU Edgbaston Lillian de Lissa Children's Centre, Bellevue, Edgbaston, B5 7LX Erdington Home Start Stockland Green/Erdington, Erdington Six Ways Baptist Church, Wood End Road, Erdington, B24 8AD Erdington Erdington Childrens Centre, Ryland Road, Erdington, B24 8JJ Four Oaks Sutton Locality Children's Centres, C/o Four Oaks Children’s Centre, Arther Terry School, Kittoe Road, Four Oaks, B74 4RZ Handsworth Lime Tree Children’s Centre, Heathfield Road, Handsworth, B19 1HJ Handsworth Rookery & Soho Children’s Centres, Soho Children’s Centre, Louise Road, Handsworth, B21 0RY Kings Heath Maypole Children’s Centre, 15 Grendon Road, Kings Heath, B14 4RB Kitts Green Kitts Green Children’s Centre, Ridpool Road, Kitts Green, B33 9RB Nechells Bloomsbury Children's Centre, Bloomsbury Street, Nechells, B7 5BX Saltley Anthony Road Children’s Centre, 80 Anthony Road, Saltley, B8 3AA Small Heath Waverley Children’s Centre, 311 Yardley Green Road, Small Heath, B9 5QA Solihull Solihull A&E, 1st Floor, 3 The Green, Stratford road, Shirley B90 4LA Stechford Bordesley Green East Nursery & Children's Centre, 358 Bordesley Green East, Stechford, B33 8QB Sutton Home-Start Sutton Coldfield, United Reformed Church, B27 Coldfield 36A West Heath Longbridge Locality Children's Centres, 49 Merrishaw Road, West Heath, B31 3SL Wolverhampton Bushbury Triangle Children's Centre, Stanley Road, Bushbury, Wolverhampton, WV10 9EL . -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

Prevention Newsletter Issue 5: 2021 Focus on Edgbaston

Prevention Newsletter Issue 5: 2021 Focus on Edgbaston Bartley Green Reservoir INTRODUCTION Welcome to our fifth newsletter! This month we are focusing on Edgbaston Constituency. The Prevention and Communities (P&C) Commissioning Team are promoting the fantastic, and wide ranging, work happening all over Birmingham. This month it is Edgbaston’s turn to showcase some of what has been achieved with our voluntary and community sector partners. This newsletter will share Edgbaston stories from the different services this team manages and supports including: The Neighbourhood Network Scheme The Prevention and Communities Grants Programme Vulnerable Adults Grants What do we mean by Prevention? Adult Social Care’s Prevention First Vision is about supporting people to lead, “happy, independent lives in their own homes and communities.” Adult Social Care has been changing how we work, taking more time to listen and understand what a good life looks like for people. We are connecting them to the support they need in their community before looking at traditional forms of care. This is known as the Three Conversations approach. To ensure there is community-based support people need and want, our commissioning team have been investing in organisations that can deliver or develop this. Our focus is on support that can improve wellbeing and independence by: reducing isolation, increasing opportunities to be active, maximising income, helping to maintain homes and supporting carers. Please tell us what you think of the newsletter We would love feedback on the newsletter to help us make these really beneficial for social work teams and others who would find these updates useful. -

Lidl Food Store, 579 Moseley Road, Sparkbrook, Birmingham, B12 9BS

Committee Date: 06/03/2014 Application Number: 2013/09221/PA Accepted: 20/12/2013 Application Type: Full Planning Target Date: 21/03/2014 Ward: Sparkbrook Lidl Food Store, 579 Moseley Road, Sparkbrook, Birmingham, B12 9BS Demolition of existing Lidl food store and industrial units on Homer Street and erection of a new enlarged food store together with car parking and landscaping works Applicant: Lidl UK GmbH Wellington Parkway, Lutterworth, Leicestershire, LE17 4XW Agent: Recommendation Approve Subject To A Section 106 Legal Agreement 1. Proposal 1.1. Consent is sought to demolish the existing Lidl food store (1100sq.m) and adjoining industrial units (400sq.m) on Homer Street and to erect a new enlarged food store (2179sq.m), together with car parking and landscaping works (site area – 6526sq.m). 1.2. The existing store has a predominantly blank frontage to Moseley Road. The majority of the car parking (88 spaces) is located behind the store. It is single storey and located close to the boundary with premises fronting Cromer Road. 1.3. The proposed new store would front Moseley Road. The proposed store would be around 3m from the rear of properties fronting Cromer Road. The proposed service yard / deliver area would be located at the rear of the store. The store would comprise; entrance area, sales area (1391sq.m), bakery preparation room, bakery freezer room, warehouse areas, delivery store, office, staff room, cloak rooms and w/c’s. 1.4. The proposed new store would be single storey, with an aluminium raised seam clad pitched roof. The Moseley Road frontage, and a portion of the return elevation to the car park, would comprise predominantly full-height glazing. -

Birmingham City Council Shard End Ward Meeting

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL SHARD END WARD MEETING MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 7PM AYLESFORD HALL 116 BRADLEY ROAD B34 6HE MEETING NOTES Present: Councillors Marje Bridle and Ian Ward Officers: Beverly Edmead – Community Governance Team Sgt Dan Turnbull – West Midlands Police Pat Whyte – Community Development & Support Unit There were approx. 70 residents present. Cllr M Bridle in the Chair 1. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS Following introductions, Cllr Bridle, Ward Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2. NOTICE OF RECORDING The Chair advised that members of the press/public may record and/or take photographs except where there were confidential or exempt items. 3. APOLOGIES An apology for absence was submitted on behalf of Cllr Cotton who was unable to attend the meeting due to illness. 4. LOCAL NEWS/INFORMATION UPDATES (i) West Midlands Police Sgt Dan Turnbull advised of the following:- - Off Road Bikes/Pedal Bikes Nuisance 30 warrants were executed at the pre-planned Halloween Ride Out event; 53 arrests were made, 7 of which were charged with serious offences. In addition, 14 bikes were seized, with several of these being from the Shard End ward. The intelligence gathered from local residents had been crucial in the success of the operation. Several young people, all of whom lived locally had been identified as the main perpetrators of pedal bikes nuisance as well as some from neighbouring Chelmsley Wood and Yorkswood. A number of partner agencies were involved with the families of the young people, and a number of conditions had been put in place to manage/change their behaviour. However, two young people were 1 still persistent in their offending and resistant to changing their behaviour. -

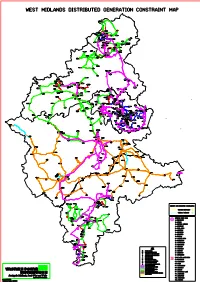

West Midlands Constraint Map-Default

WEST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP CONGLETON LEEK KNYPERSLEY PDX/ GOLDENHILL PKZ BANK WHITFIELD TALKE KIDSGROVE B.R. 132/25KV POP S/STN CHEDDLETON ENDON 15 YS BURSLEM CAULDON 13 CEMENT STAUNCH CELLARHEAD STANDBY F11 CAULDON NEWCASTLE FROGHALL TQ TR SCOT HAY STAGEFIELDS 132/ STAGEFIELDS MONEYSTONE QUARRY 33KV PV FARM PAE/ PPX/ PZE PXW KINGSLEY BRITISH INDUSTRIAL HEYWOOD SAND GRANGE HOLT POZ FARM BOOTHEN PDY/ PKY 14 9+10 STOKE CHEADLE C H P FORSBROOK PMZ PUW LONGTON SIMPLEX HILL PPW TEAN CHORLTON BEARSTONE P.S LOWER PTX NEWTON SOLAR FARM MEAFORD PCY 33KV C 132/ PPZ PDW PIW BARLASTON HOOKGATE PSX POY PEX PSX COTES HEATH PNZ MARKET DRAYTON PEZ ECCLESHALL PRIMARY HINSTOCK HIGH OFFLEY STAFFORD STAFFORD B.R. XT XT/ PFZ STAFFORD SOUTH GNOSALL PH NEWPORT BATTLEFIELD ERF GEN RUGELEY RUGELEY TOWN RUGELEY SWITCHING SITE HARLESCOTT SUNDORNE SOLAR FARM SPRING HORTONWOOD PDZ/ GARDENS PLX 1 TA DONNINGTON TB XBA SHERIFFHALES XU SHREWSBURY DOTHILL SANKEY SOLAR FARM ROWTON ROUSHILL TN TM 6 WEIR HILL LEATON TX WROCKWARDINE TV SOLAR LICHFIELD FARM SNEDSHILL HAYFORD KETLEY 5 SOLAR FARM CANNOCK BAYSTON PCD HILL BURNTWOOD FOUR ASHES PYD PAW FOUR ASHES E F W SHIFNAL BERRINGTON CONDOVER TU TS SOLAR FARM MADELEY MALEHURST ALBRIGHTON BUSHBURY D HALESFIELD BUSHBURY F1 IRONBRIDGE 11 PBX+PGW B-C 132/ PKE PITCHFORD SOLAR FARM I54 PUX/ YYD BUSINESS PARK PAN PBA BROSELEY LICHFIELD RD 18 GOODYEARS 132kV CABLE SEALING END COMPOUND 132kV/11kV WALSALL 9 S/STN RUSHALL PATTINGHAM WEDNESFIELD WILLENHALL PMX/ BR PKE PRY PRIESTWESTON LEEBOTWOOD WOLVERHAMPTON XW -

Birmingham a Powerful City of Spirit

Curriculum Vitae Birmingham A powerful city of spirit Bio Timeline of Experience Property investment – As the second largest city in the UK, I have a lot to offer. I have great Birmingham, UK connections thanks to being so centrally located, as over 90% of the UK market is only a four hour drive away. The proposed HS2 railway is poised I’ve made a range to improve this further – residents will be able to commute to London in of investments over less than an hour. I thrive in fast-paced environments, as well as calmer the years. The overall waters – my vast canal route covers more miles than the waterways average house price is of Venice. £199,781, up 6% up 2018 - 2019 - 2019 2018 on the previous year. Truly a national treasure, my famed Jewellery Quarter contains over 800 businesses specialising in handcrafted or vintage jewellery and produces 40% of the UK’s jewellery. Edgbaston is home to the famed cricket ground Job application surge – and sees regular county matches, alongside the England cricket team for Birmingham, UK international or test matches. My creative and digital district, the Custard I’ve continued to refine Factory, is buzzing with artists, innovators, developers, retailers, chefs and my Sales and Customer connoisseurs of music. Other key trades include manufacturing (largely Service skills, seeing a cars, motorcycles and bicycles), alongside engineering and services. rise in job applications of 34% and 29% between May 2018 2018 - 2019 2018 Education Skills and January 2019. 4 I have an international Launch of Birmingham Festivals – universities including the perspective, with Brummies Birmingham, UK University of Birmingham, Aston, hailing from around the world Newman and Birmingham City.