Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Design and Printing: Lynx DPM Limited Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2015 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] The editor would like to thank Rachel Pearson, Julian Reid, Sara Watson and David Wilson. Front cover: The Library, by former artist-in-residence Ceri Allen. By kind permission of Nick Thorn Back cover: Stone pelican in Durham Castle, carved during Richard Fox’s tenure as Bishop of Durham. Photograph by Peter Rhodes ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report ................................................................................... 3 President’s Seminar: Casting the Audience Peter Nichols ............................................................................................ 11 Bishop Foxe’s Humanistic Library and the Alchemical Pelican Alexandra Marraccini ................................................................................ 17 Remembrance Day Sermon A sermon delivered by the President on 9 November 2014 ....................... 22 Corpuscle Casualties from the Second World War Harriet Fisher ............................................................................................. 27 A Postgraduate at Corpus Michael Baker ............................................................................................. 34 Law at Corpus Lucia Zedner and Liz Fisher .................................................................... -

The Kremlin Trojan Horses | the Atlantic Council

Atlantic Council DINU PATRICIU EURASIA CENTER THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister, and Neil Barnett Foreword by Radosław Sikorski THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister, and Neil Barnett Foreword by Radosław Sikorski ISBN: 978-1-61977-518-3. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. November 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword Introduction: The Kremlin’s Toolkit of Influence 3 in Europe 7 France: Mainstreaming Russian Influence 13 Germany: Interdependence as Vulnerability 20 United Kingdom: Vulnerable but Resistant Policy recommendations: Resisting Russia’s 27 Efforts to Influence, Infiltrate, and Inculcate 29 About the Authors THE KREMLIN’S TROJAN HORSES FOREWORD In 2014, Russia seized Crimea through military force. With this act, the Kremlin redrew the political map of Europe and upended the rules of the acknowledged international order. Despite the threat Russia’s revanchist policies pose to European stability and established international law, some European politicians, experts, and civic groups have expressed support for—or sympathy with—the Kremlin’s actions. These allies represent a diverse network of political influence reaching deep into Europe’s core. The Kremlin uses these Trojan horses to destabilize European politics so efficiently, that even Russia’s limited might could become a decisive factor in matters of European and international security. -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Ethnic Diversity in Politics and Public Life

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 01156, 22 October 2020 By Elise Uberoi and Ethnic diversity in politics Rebecca Lees and public life Contents: 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 2. Parliament 3. The Government and Cabinet 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 5. Public sector organisations www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Ethnic diversity in politics and public life Contents Summary 3 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 6 1.1 Categorising ethnicity 6 1.2 The population of the United Kingdom 7 2. Parliament 8 2.1 The House of Commons 8 Since the 1980s 9 Ethnic minority women in the House of Commons 13 2.2 The House of Lords 14 2.3 International comparisons 16 3. The Government and Cabinet 17 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 19 4.1 Devolved legislatures 19 4.2 Local government and the Greater London Authority 19 5. Public sector organisations 21 5.1 Armed forces 21 5.2 Civil Service 23 5.3 National Health Service 24 5.4 Police 26 5.4 Justice 27 5.5 Prison officers 28 5.6 Teachers 29 5.7 Fire and Rescue Service 30 5.8 Social workers 31 5.9 Ministerial and public appointments 33 Annex 1: Standard ethnic classifications used in the UK 34 Cover page image copyright UK Youth Parliament 2015 by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped 3 Commons Library Briefing, 22 October 2020 Summary This report focuses on the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in a range of public positions across the UK. -

Turkey's EU Accession As a Factor in the 2016 Brexit Referendum

James Ker-Lindsay Turkey’s EU accession as a factor in the 2016 Brexit referendum Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Ker-Lindsay James. (2017). Turkey’s EU accession as a factor in the 2016 Brexit referendum. Turkish Studies. ISSN 1468-3849. DOI: 10.1080/14683849.2017.1366860 © 2017 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/83691/ Available in LSE Research Online: October 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Turkey’s EU Accession as a Factor in the 2016 Brexit Referendum James Ker-Lindsay European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Twitter http://www.twitter.com/JamesKerLindsay Biographical note James Ker-Lindsay is Senior Visiting Fellow at the European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science and Research Associate at the Centre for International Studies at the University of Oxford. -

Wh Owat Ches the Wat Chmen

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

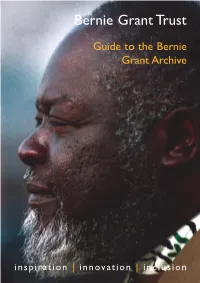

Guide to the Archive

Bernie Grant Trust Guide to the Bernie Grant Archive inspiration | innovation | inclusion Contents Compiled by Dr Lola Young OBE Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion . 4 Edited by Machel Bogues What’s in the Bernie Grant Archive? . 11 How it’s organised . 14 Index entries . 15 Tributes - 2000 . 16 What are Archives? . 17 Looking in the Archives . 17 Why Archives are Important . 18 What is the Value of the Bernie Grant Archive? . 18 How we set up the Bernie Grant Collection . 20 Thank you . 21 Related resources . 22 Useful terms . 24 About The Bernie Grant Trust . 26 Contacting the Bernie Grant Archive . 28 page | 3 Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion Born into a family of educationalists on London. The 4000 and overseas. He was 17 February 1944 in n 18 April 2000 people who attended a committed anti-racist Georgetown, Guyana, thousands of O the service at Alexandra activist who campaigned Bernie Grant was the people lined the streets Palace made this one of against apartheid South second of five children. of Haringey to follow the largest ever public Africa, against the A popular, sociable child the last journey of a tributes at a funeral of a victimisation of black at primary school, he charismatic political black person in Britain. people by the police won a scholarship to leader. Bernie Grant had in Britain and against St Stanislaus College, a been the Labour leader Bernie Grant gained racism in health services Jesuit boys’ secondary of Haringey Council a reputation for being and other public and school. Although he during the politically controversial because private institutions. -

On Parliamentary Representation)

House of Commons Speaker's Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) Session 2008–09 Volume II Written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 21 April 2009 HC 167 -II Published on 27 May 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Speaker’s Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) The Conference secretariat will be able to make individual submissions available in large print or Braille on request. The Conference secretariat can be contacted on 020 7219 0654 or [email protected] On 12 November 2008 the House of Commons agreed to establish a new committee, to be chaired by the Speaker, Rt. Hon. Michael Martin MP and known as the Speaker's Conference. The Conference has been asked to: "Consider, and make recommendations for rectifying, the disparity between the representation of women, ethnic minorities and disabled people in the House of Commons and their representation in the UK population at large". It may also agree to consider other associated matters. The Speaker's Conference has until the end of the Parliament to conduct its inquiries. Current membership Miss Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) (Vice-Chairman) Ms Diane Abbott MP (Labour, Hackney North & Stoke Newington) John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Mr David Blunkett MP (Labour, Sheffield, Brightside) Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton & Honiton) Mr Ronnie Campbell MP (Labour, Blyth Valley) Mrs Ann Cryer MP (Labour, Keighley) Mr Parmjit Dhanda MP (Labour, Gloucester) Andrew George MP (Liberal Democrat, St Ives) Miss Julie Kirkbride MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove) Dr William McCrea MP (Democratic Unionist, South Antrim) David Maclean MP (Conservative, Penrith & The Border) Fiona Mactaggart MP (Labour, Slough) Mr Khalid Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham Perry Barr) Anne Main MP (Conservative, St Albans) Jo Swinson MP (Liberal Democrat, East Dunbartonshire) Mrs Betty Williams MP (Labour, Conwy) Publications The Reports and evidence of the Conference are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

FILE 1 – Body Shaming Document 2 Document 3 - "Love Is Blind" Highlights Reality TV's Fatphobia Problem Teen Vogue, March 5, 2020, by Mathew Rodriguez

FILE 1 – Body shaming Document 2 Document 3 - "Love Is Blind" Highlights Reality TV's Fatphobia Problem Teen Vogue, March 5, 2020, by Mathew Rodriguez Not having any plus-size people as part of the experiment undercuts any thesis the show purports to test. In this op-ed, writer Mathew Rodriguez unpacks how Netflix’s dating reality show "Love Is Blind" purports to test whether sparks can fly between people who have never seen each other before — yet doesn’t include fat people. Within the first few minutes of Love Is Blind on Netflix, host Vanessa Lachey, standing next to her husband, 98 Degrees frontman Nick Lachey, delivers the show’s premise. She says to the participating women, “Everyone wants to be loved for who they are. Not for their looks, their race, their background or their income.” To counteract the world of Tinder, Grindr, and other dating apps, which give users the chance to reject or accept a person based solely on a photo, Blind challenges people to fall in love without ever having seen their potential partners. Couples will date and forge connections in furnished pods from opposite sides of a wall. The show does make good on at least three of those promises: It does have couples that are from different economic backgrounds, different upbringings, and across races. But, for all the differences the show derives drama from, it leaves one notable exception to its experiment: weight. Love Is Blind features all average-bodied people. And while it does want to test how people find love regardless of race and class, it never even nods to people’s size. -

A Study of Identity, Ethics and Power in the Relationship Between Britain and the United Kingdom Overseas Territories

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2013 Distant Relations: A Study of Identity, Ethics and Power in the Relationship Between Britain and the United Kingdom Overseas Territories Harmer, Nichola http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1575 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. DISTANT RELATIONS: A STUDY OF IDENTITY, ETHICS AND POWER IN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BRITAIN AND THE UNITED KINGDOM OVERSEAS TERRITORIES By NICHOLA HARMER A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science December 2012 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. ABSTRACT Nichola Harmer DISTANT RELATIONS: A STUDY OF IDENTITY, ETHICS AND POWER IN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BRITAIN AND THE UNITED KINGDOM OVERSEAS TERRITORIES This thesis contributes to new understandings of the contemporary relationship between Britain and the fourteen remaining United Kingdom Overseas Territories. By examining the discourse of social and political elites in Britain and in several Overseas Territories, it identifies the significance of the role of identity in shaping perceptions and relations between these international actors. -

Race and Elections

Runnymede Perspectives Race and Elections Edited by Omar Khan and Kjartan Sveinsson Runnymede: Disclaimer This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives Intelligence for a series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented Multi-ethnic Britain and views expressed in this publication are, however, those of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the Runnymede Trust. Runnymede is the UK’s leading independent thinktank on race equality ISBN: 978-1-909546-08-0 and race relations. Through high-quality research and thought leadership, we: Published by Runnymede in April 2015, this document is copyright © Runnymede 2015. Some rights reserved. • Identify barriers to race equality and good race Open access. Some rights reserved. relations; The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of • Provide evidence to its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. support action for social The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone change; to access its content online without charge. Anyone can • Influence policy at all download, save, perform or distribute this work in any levels. format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. You are welcome to ask Runnymede for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence.