Contesting Sacred Architecture: Politics of ‘Nation-State’ in the Battles of Mosques in Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics of Indonesian Intercultural Sensitivity in Multicultural and International Work Groups Hana Panggabean Atma Jaya Indonesia Catholic University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2004 Characteristics of Indonesian Intercultural Sensitivity in Multicultural and International Work Groups Hana Panggabean Atma Jaya Indonesia Catholic University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Panggabean, H. (2004). Characteristics of Indonesian intercultural sensitivity in multicultural and international work groups. In B. N. Setiadi, A. Supratiknya, W. J. Lonner, & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), Ongoing themes in psychology and culture: Proceedings from the 16th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/239 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology Conferences by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 565 CHARACTERISTICS OF INDONESIAN INTERCULTURAL SENSITIVITY IN MULTICULTURAL AND INTERNATIONAL WORKGROUPS Hana Panggabean Atma Jaya Indonesia Catholic University Jakarta, Indonesia Intercultural Sensitivity (JCS) is an important socio-cultural variable in dealing with intercultural contexts such as multicultural societies and over seas assignments. The variable covers skills to manage and make -

Gus Dur, As the President Is Usually Called

Indonesia Briefing Jakarta/Brussels, 21 February 2001 INDONESIA'S PRESIDENTIAL CRISIS The Abdurrahman Wahid presidency was dealt a devastating blow by the Indonesian parliament (DPR) on 1 February 2001 when it voted 393 to 4 to begin proceedings that could end with the impeachment of the president.1 This followed the walk-out of 48 members of Abdurrahman's own National Awakening Party (PKB). Under Indonesia's presidential system, a parliamentary 'no-confidence' motion cannot bring down the government but the recent vote has begun a drawn-out process that could lead to the convening of a Special Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) - the body that has the constitutional authority both to elect the president and withdraw the presidential mandate. The most fundamental source of the president's political vulnerability arises from the fact that his party, PKB, won only 13 per cent of the votes in the 1999 national election and holds only 51 seats in the 500-member DPR and 58 in the 695-member MPR. The PKB is based on the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a traditionalist Muslim organisation that had previously been led by Gus Dur, as the president is usually called. Although the NU's membership is estimated at more than 30 million, the PKB's support is drawn mainly from the rural parts of Java, especially East Java, where it was the leading party in the general election. Gus Dur's election as president occurred in somewhat fortuitous circumstances. The front-runner in the presidential race was Megawati Soekarnoputri, whose secular- nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) won 34 per cent of the votes in the general election. -

The Protection of Indonesian Batik Products in Economic Globalization

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 192 1st International Conference on Indonesian Legal Studies (ICILS 2018) The Protection of Indonesian Batik Products in Economic Globalization Dewi Sulistianingsih1a, Pujiono1b 1Department of Private and Commercial Law , Faculty of Law, Universitas Negeri Semarang (UNNES), Indonesia a [email protected], b [email protected] Abstract— Batik is one of Indonesia’s cultural heritage whose existence has been recognized by UNESCO since 2009. It has become the identity and characteristic of Indonesia that needs to be preserved and developed. Indonesian people can preserve it by recognizing its products’ existence and conducting development efforts by improving the quality of its products. In Indonesia, batik has been passed down from generations by wearing, producing and marketing its products. The article is the result of a study using a socio-legal method. The data collection was conducted through interview and observation techniques. The research subjects are batik business owners in Indonesia. This paper reveals the challenges and obstacles faced by the local batik product business people in Indonesia in the face of economic globalization. There have been legal efforts to provide protection for the Indonesian batik products. The problems are how the protection is applied and how the country and the community perform the protection. The other objective of this paper is to analyze the readiness of the local batik businesspeople in Indonesia in the face of economic globalization especially from the legal perspective. The article exposes the batik business owners’ weaknesses and seeks to give sound solutions which is hoped to be applied by the batik business owners in Indonesia in order to survive in the globalization era. -

Kearifan Lokal Tahlilan-Yasinan Dalam Dua Perspektif Menurut Muhammadiyah

KEARIFAN LOKAL TAHLILAN-YASINAN DALAM DUA PERSPEKTIF MENURUT MUHAMMADIYAH Khairani Faizah Jurusan Pekerjaan Sosial Program Pascasarjana Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan kalijaga Yogyakarta [email protected] Abstract. Tahlilan or selamatan have been rooted and become a custom in the Javanese society. Beginning of the selamatan or tahlilan is derived from the ceremony of ancestors worship of the Nusantara who are Hindus and Buddhists. Indeed tahlilan-yasinan is a form of local wisdom from the worship ceremony. The ceremony as a form of respect for people who have released a world that is set at a time like the name of tahlilan-yasinan. In the perspective of Muhammadiyah, the innocent tahlilan-yasinan with the premise that human beings have reached the points that will only get the reward for their own practice. In addition, Muhammadiyah people as well as many who do tahlilan-yasinan ritual are received tahlian-yasinan as a form of cultural expression. Therefore, this paper conveys how Muhammadiyah deal with it in two perspectives and this paper is using qualitative method. Both views are based on the interpretation of the journey of the human spirit. The human spirit, writing apart from the body, will return to God. Whether the soul can accept the submissions or not, the fact that know the provisions of a spirit other than Allah swt. All human charity can not save itself from the punishment of hell and can not put it into heaven other than by the grace of Allah swt. Keywords: Tahlilan, Bid’ah, Muhammadiyah Abstrak. Ritual tahlilan atau selamatan kematian ini sudah mengakar dan menjadi budaya pada masyarakat Jawa yang sangat berpegang teguh pada adat istiadatnya. -

The Influence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Chinese Culture on the Shapes of Gebyog of the Javenese Traditional Houses

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.79, 2019 The Influence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Chinese Culture on the Shapes of Gebyog of the Javenese Traditional Houses Joko Budiwiyanto 1 Dharsono 2 Sri Hastanto 2 Titis S. Pitana 3 Abstract Gebyog is a traditional Javanese house wall made of wood with a particular pattern. The shape of Javanese houses and gebyog develop over periods of culture and government until today. The shapes of gebyog are greatly influenced by various culture, such as Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, and Chinese. The Hindu and Buddhist influences of are evident in the shapes of the ornaments and their meanings. The Chinese influence through Islamic culture developing in the archipelago is strong, mainly in terms of the gebyog patterns, wood construction techniques, ornaments, and coloring techniques. The nuance has been felt in the era of Majapahit, Demak, Mataram and at present. The use of ganja mayangkara in Javanese houses of the Majapahit era, the use of Chinese-style gunungan ornaments at the entrance to the Sunan Giri tomb, the saka guru construction technique of Demak mosque, the Kudusnese and Jeparanese gebyog motifs, and the shape of the gebyog patangaring of the house. Keywords: Hindu-Buddhist influence, Chinese influence, the shape of gebyog , Javanese house. DOI : 10.7176/ADS/79-09 Publication date: December 31st 2019 I. INTRODUCTION Gebyog , according to the Javanese-Indonesian Dictionary, is generally construed as a wooden wall. In the context of this study, gebyog is a wooden wall in a Javanese house with a particular pattern. -

Estetika Barang Kagunan Interior Dalem Ageng Di Rumah Kapangéranan Keraton Surakarta

ESTETIKA BARANG KAGUNAN INTERIOR DALEM AGENG DI RUMAH KAPANGÉRANAN KERATON SURAKARTA DISERTASI Untuk memenuhi sebagian persyaratan guna memperoleh gelar Doktor Program Studi Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Jalur Pengkajian Seni - Minat Seni Rupa dan Desain Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI) Surakarta diajukan oleh: Rahmanu Widayat NIM: 11312110 Kepada PROGRAM PASCASARJANA INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA (ISI) SURAKARTA 2016 ii DISERTASI ESTETIKA BARANG KAGUNAN INTERIOR DALEM AGENG DI RUMAH KAPANGERANAN KERATON SURAKARTA Dipersiapkan dan disusun oleh : Rahmanu Widayat NIM : 11312110 Telah dipertahankan didipan Dewan Penguji Pada tanggal 28 Januari 2016 iii iv HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Persembahan khusus untuk Prof. Ir. Eko Budihardjo, M.Sc. – almarhum– selaku Co-Promotor, sebuah puisi dari penulis atas permintaan beliau sebelum meninggal dunia. Sms Prof Eko: “Bila berkenan n ada waktu dimohon mas Rahmanu menulis puisi seenaknya menyangkut Kehidupan dan Kematian, sbg kado Ultah ke 70 saya, akan dibukukan n diluncurkan di Undip Smg tgl 9 Juni 2014. Tenggat waktu –deadline– tg 11 April 2014”., Ini puisi penulis –yang tidak pernah bikin puisi– untuk Prof. Eko tentang Kehidupan dan Kematian: Sangkan Paraning Dumadi Dari mana asal Apa itu hidup Kemana setelah mati Lahir disambut bahagia Mati diantar duka Hidup di antara bahagia dan duka Bahagia syukur Duka sabar Dengan begitu tahu rumah Tahu jalan pulang Sms Prof. Eko: Beribu tks atas kiriman puisinya. Tolong kirim biodata, singkat saja. Oh ya, tolong kirim nama n no hp promotor dan Ketua ISI Solo. Salam hangat. Eko. Sms Prof. Dhar –promotor penulis– ke penulis, info dari Merdeka.Com: Prof. Eko Budihardjo wafat selasa 22/7 pukul 21.30. Sms Penulis ke hp almarhum: Innalillahi wa ina ilaihi ro jiun, selamat jalan Prof. -

Hans Harmakaputra, Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia

Key Issues in Religion and World Affairs Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia: Challenges and Progress Hans Abdiel Harmakaputra PhD Student in Comparative Theology, Boston College I. Introduction In February 2014 Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) published a report concerning the rise of religious intolerance across Indonesia. Entitled Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,1 this study portrays the problems plaguing interfaith relations in Indonesia, where many religious minorities suffer from persecution and injustice. The report lists five main factors contributing to the rise of religious intolerance: (1) the spread of extremist ideology through media channels, such as the internet, religious pamphlets, DVDs, and other means, funded from inside and outside the country; (2) the attitude of local, provincial, and national authorities; (3) the implementation of discriminatory laws and regulations; (4) weakness of law enforcement on the part of police and the judiciary in cases where religious minorities are victimized; and (5) the unwillingness of a “silent majority” to speak out against intolerance.2 This list of factors shows that the government bears considerable responsibility. Nevertheless, the hope for a better way to manage Indonesia’s diversity was one reason why Joko Widodo was elected president of the Republic of Indonesia in October 2014. Joko Widodo (popularly known as “Jokowi”) is a popular leader with a relatively positive governing record. He was the mayor of Surakarta (Solo) from 2005 to 2012, and then the governor of Jakarta from 2012 to 2014. People had great expectations for Jokowi’s administration, and there have been positive improvements during his term. However, Human Rights Watch (HRW) World Report 2016 presents negative data regarding his record on human rights in the year 2015, including those pertaining to interfaith relations.3 The document 1 The pdf version of the report can be downloaded freely from Christian Solidarity Worldwide, “Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,” February 14, 2014. -

Karakteristik Sistem Struktur Ruang Utama Masjid Agung Demak

TEMU ILMIAH IPLBI 2016 Karakteristik Sistem Struktur Ruang Utama Masjid Agung Demak Mohhamad Kusyanto(1), Debagus Nandang(1), Erlin Timor Tiningsih(2), Bambang Supriyadi(3), Gagoek Hardiman(3) (1)Program Studi Teknik Arsitektur, Fakultas Teknik, Universitas Sultan Fatah Demak. (2)Program Studi Teknik Informatika, Fakultas Teknik, Universitas Sultan Fatah Demak. (3)Program Studi Teknik Arsitektur, Fakultas Teknik, Universitas Diponegoro Semarang. Abstrak Masjid Agung Demak merupakan salah satu masjid tertua di Pulau Jawa. Masjid ini memiliki ruang utama yang besar sehingga untuk menaungi ruang ini diperlukan struktur atap yang besar dan kokoh. Struktur Masjid Agung Demak memiliki karakteristik yang berbeda dengan masjid yang lain. Artikel ini bertujuan untuk mendapatkan gambaran/pemahaman struktur Masjid Agung Demak yang memiliki bentang yang besar. Metode yang digunakan adalah penelitian kualitatif dengan kategori sifat penelitian deskriptif eksploratif. Pengumpulan data dengan survei dan observasi langsung ke Masjid Agung Demak, penelusuran bahan pustaka, wawancara, pengukuran dan penggambaran serta dokumentasi. Analisis yang digunakan adalah deskriptif-analitis melalui gambar-gambar atau foto-foto dan sketsa. Dalam penelitian ini ditemukan karakteristik sistem struktur bentang lebar Masjid Agung Demak yang memiliki keunikan dalam mempertahankan sistem struktur sejak awal pendiriannya, penggunaan kayu dalam menyelesaikan bentang lebar masjid dan membagi sistem struktur dalam tiga susun tajug. Kata-kunci : Demak, karakteristik, masjid, sistem, struktur Pendahuluan Masjid Agung Demak termasuk masjid yang besar dikarenakan memiliki ruang utama sholat Masjid Agung Demak yang diduga didirikan pada berbentuk bujur sangkar berukuran 24 x 24 tahun 1479 (Sumalyo, 2000) dan telah berdiri meter dengan penutup atap tajug susun tiga, kokoh sampai saat ini. Masjid Agung Demak sehingga membutuhkan struktur ruang utama adalah salah satu masjid tertua di Pulau Jawa yang kuat. -

NEW INTERPRETATION on PROHIBITION to SLAUGHTER COW for KUDUS SOCIETY (Paul Ricoeur‟S Social Hermeneutic Perspective)

1 NEW INTERPRETATION ON PROHIBITION TO SLAUGHTER COW FOR KUDUS SOCIETY (Paul Ricoeur‟s Social Hermeneutic Perspective) THESIS Submitted to Ushuluddin and Humanity Faculty in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of S-1 on Theology and Philosophy Departement Written by: Yulinar Aini Rahmah NIM: 124111038 SPECIAL PROGRAM OF USHULUDDIN AND HUMANITY FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY (UIN) WALISONGO SEMARANG 2016 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is definitely my own work. I am completely responsible for content of this thesis. Other writer‟s opinions or findings included in the thesis are quoted or cited in accordance with ethical standards. Semarang, May 18, 2016 The Writer, Yulinar Aini Rahmah NIM. 124111038 3 4 5 MOTTO O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of a male and a female, and made you into nations and tribes, that you may know each other (not that you may despise (each other). Verily the most honoured of you in the sight of Allah is (he who is) the most righteous of you. And Allah has full knowledge and is well acquinted (with all things). -Al-Hujuraat 13- 6 DEDICATION This Thesis is dedicated to: My beloved Mom and Dad, My Brother and My Sister, My Teachers , And everyone who loves the wisdom 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . All praises and thanks are always delivered unto Allah for his mercy and blessing. Furthemore, may peace and respect are always given to Muhammad peace unto him who has taught wisdom for all mankind. By saying Alhamdulillah, the writer presents this thesis entittled: NEW INTERPRETATION ON PROHIBITION TO SLAUGHTER COW FOR KUDUS SOCIETY (Paul Ricoeur‟s Social Hermeneutic Perspective) to be submitted on Ushuluddin and Humanity Faculty in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of S-1 on Theology and Philosophy Departement. -

6D5n Lake Toba – Bohorok Tour

Warmest Greetings from Universal Tour & Travel has been established since 1966 and is one of the leading Travel Company in Indonesia. Along with our experienced and professional managers and tour- guides in the year 2016, we are ready to serve you for the coming 50 years. We appreciate very much for your trust and cooperation to us in the past and are looking forward to your continued support in the future. We wish 2016 will bring luck and prosperity to all of us. Jakarta, 01 January 2016 The Management of Universal Tour & Travel Table of Contents - Introduction 3 - Company Profile 4 - Our Beautiful Indonesia 5 - Sumatera 6 - Java 16 - Bali 40 - Lombok 48 - Kalimantan 56 - Sulawesi 62 - Irian Jaya 71 3 Company Profile Registered Name : PT. Chandra Universal Travel (Universal Tour & Travel) Established on : August 26, 1966 License No. : 100/D.2/BPU/IV/79 Member of : IATA, ASITA, ASTINDO, EKONID Management - Chairman : Dipl Ing. W.K. Chang - Executive Director : Hanien Chang - Business Development Director : Hadi Saputra Kurniawan - Tour Manager : I Wayan Subrata - Asst. Tour Manager : Ika Setiawaty - Travel Consultant Manager : Nuni - Account Manager : Sandhyana Company Activities - Ticketing (Domestic and International) - Inbound Tours - Travel Documents - Domestic Tours - Car & Bus Rental - Outbound Tours - Travel Insurance - Hotel Reservation Universal Tour & Travel was founded by Mr. Chang Chean Cheng (Chandra Kusuma) on 26 August 1966 and member of IATA in 1968 respectively. In the year between 1966 -1970, there were around 200 travel agents with or without travel agent licence and around 35 IATA agents. Our company started from 8-12 staffs in charged for Ticketing, Inbound Tour and Administration. -

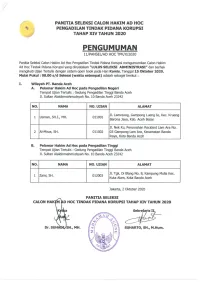

PENGUMUMAN Ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020

PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : I. Wilayah PT. Banda Aceh A. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Negeri Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Lamreung, Gampong Lueng Ie, Kec. Krueng 1 Usman, SH.I., MH. 011001 Barona Jaya, Kab. Aceh Besar Jl. Nek Ku, Perumahan Recident Lam Ara No. 2 Al-Mirza, SH. 011002 03 Gampong Lam Ara, Kecamatan Banda Raya, Kota Banda Aceh B. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Tinggi Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Tgk. Di Blang No. 8, Kampung Mulia Kec. 1 Zaini, SH. 012003 Kuta Alam, Kota Banda Aceh Jakarta, 2 Oktober 2020 PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 Dr. SUHA SUHARTO, SH., M.Hum. PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : II. -

Translating Modern Ideas Into Postcolonial Mosque Architecture in Indonesia

International Journal of Built Environment and Scientific Research Volume 02 Number 01 | June 2018 p-issn: 2581-1347 | e-issn: 2580-2607 | Pg. 39-46 Translating Modern Ideas into Postcolonial Mosque Architecture in Indonesia Mushab Abdu Asy Syahid1 1 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper tries to narrate the story of translation practices on the ideas and forms of modernity in the history of mosque architecture design development in Indonesia. The allow interactions to produce various approaches wider beyond religious context. The translation theory in postcolonialism field offers an alternate history on how postcolonial subjects define and take a significant role for their own culture in compromising the overcoming globalism and modernities. This attitude will question our historical narratives socio-political postcolonial subjects engage through such essential elements. In that way, a previous common image of mosque design thus ought to be reinvestigated, as well as a notion of “modern” in Indonesia history would be redeveloped while layering mosque architecture periodization. The mosque architecture types which were inspired from both Western—Eastern styles inevitably involved colonial-postcolonial contextuality in how dynamism of interchanges since Independence period interlinked to Dutch-Indies colonial times, Old and New Order regimes, to the Post-reform era interwoven present. Understanding this modernity translation transformation on each period following the spirit of the age may conclude that modern mosque architecture in Indonesia is not in a stagnant or linear but rather a complex flow periodization of its development. This also indicates the notion of “modern” has multiple intentions to culture and socio-political factors that always never solidify to any single universal definition.