Jewish Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

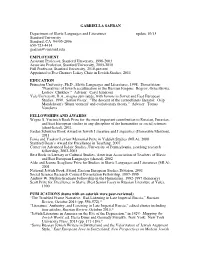

Safran CV for Profile November 2019

GABRIELLA SAFRAN Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures update 11/19 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2006 650-723-4414 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Stanford University, 1998-2003 Associate Professor, Stanford University, 2003-2010 Full Professor, Stanford University, 2010-present Appointed to Eva Chernov Lokey Chair in Jewish Studies, 2011 EDUCATION Princeton University, Ph.D., Slavic Languages and Literatures, 1998. Dissertation: "Narratives of Jewish acculturation in the Russian Empire: Bogrov, Orzeszkowa, Leskov, Chekhov." Adviser: Caryl Emerson Yale University, B.A., magna cum laude, with honors in Soviet and East European Studies, 1990. Senior Essay: "The descent of the raznochinets literator: Osip Mandelstam's 'Shum vremeni' and evolutionary theory." Adviser: Tomas Venclova FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Stanford Humanities Center, Ellen Andrews Wright Fellowship, 2015-2016 Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences (short-listed), 2011 Jordan Schnitzer Book Award in Jewish Literature and Linguistics (Honorable Mention), 2011 Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies (MLA), 2008 Stanford Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007 Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania, yearlong research fellowship, 2002-2003 Best Book in Literary or Cultural Studies, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (shared), 2002 -

2000.03.07. Ceu 1

2000.03.07. CEU 1 SPLIT IN TWO OR DOUBLED? Zsuzsa Hetényi The title is taken from an article by Iosif Bikerman published in 1910.1 There it is presented as a statement (‘not split in two but doubled’), but I shall consider it as a question because the history of Russian Jewish literature is not only a thing of the past: Russian Jewish authors began to ask questions that we continue to ask even today and that we cannot yet answer. My purpose in this paper is threefold: to discuss some theoretical questions, to give a short survey of the 80 years of Russian Jewish literature, and finally to analyse a short story by Lev Lunz. First, I would like to say something about how I arrived at this topic. In 1991 I published a book on Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry,2 a collection of 35 stories based on the writer’s experiences with Budenny’s Cavalry in 1920. The main issue for me was what problems led Babel to this unusual form of self-expression. The most important layer of this cycle of stories is Babel’s duality, which is expressed in various ways. ‘I am an outsider, in long trousers, I don’t belong, I’m all alone’, he writes in his diary of 1920.3 Babel is ambivalent about his Jewishness – he belongs organically to his people and at the same time he finds them repellent. Sometimes he lies to his fellow Jews, hiding his Jewishness. When going to the synagogue, he is moved by the service but unable to follow it in his prayer book. -

Fulfillmenttheep008764mbp.Pdf

FULFILLMENT ^^^Mi^^if" 41" THhODOR HERZL FULFILLMENT: THE EPIC STORY OF ZIONISM BY RUFUS LEARSI The World Publishing Company CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK Published by The World Publishing Company FIRST EDITION HC 1051 Copyright 1951 by Rufus Learsi All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a newspaper or magazine. Manufactured in the United States of America. Design and Typography by Jos. Trautwein. TO ALBENA my wife, who had no small part in the making of this book be'a-havah rabbah FOREWORD MODERN or political Zionism began in 1897 when Theodor Herzl con- vened the First Zionist Congress and reached its culmination in 1948 when the State of Israel was born. In the half century of its career it rose from a parochial enterprise to a conspicuous place on the inter- national arena. History will be explored in vain for a national effort with roots imbedded in a remoter past or charged with more drama and world significance. Something of its uniqueness and grandeur will, the author hopes, flow out to the reader from the pages of this narrative. As a repository of events this book is not as inclusive as the author would have wished, nor does it make mention of all those who labored gallantly for the Zionist cause across the world and in Pal- estine. Within the compass allotted for this work, only the more significant events could be included, and the author can only crave forgiveness from the actors living and dead whose names have been omitted or whose roles have perhaps been understated. -

Safran CV October 2013(1)

GABRIELLA SAFRAN Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures update 10/13 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2006 650-723-4414 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Stanford University, 1998-2003 Associate Professor, Stanford University, 2003-2010 Full Professor, Stanford University, 2010-present Appointed to Eva Chernov Lokey Chair in Jewish Studies, 2011 EDUCATION Princeton University, Ph.D., Slavic Languages and Literatures, 1998. Dissertation: "Narratives of Jewish acculturation in the Russian Empire: Bogrov, Orzeszkowa, Leskov, Chekhov." Adviser: Caryl Emerson Yale University, B.A., magna cum laude, with honors in Soviet and East European Studies, 1990. Senior Essay: "The descent of the raznochinets literator: Osip Mandelstam's 'Shum vremeni' and evolutionary theory." Adviser: Tomas Venclova FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences (short-listed), 2011 Jordan Schnitzer Book Award in Jewish Literature and Linguistics (Honorable Mention), 2011 Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies (MLA), 2008 Stanford Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007 Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania, yearlong research fellowship, 2002-2003 Best Book in Literary or Cultural Studies, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (shared), 2002 Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures (MLA), 2001 National Jewish Book Award, Eastern European Studies Division, 2001 Social Science Research Council Dissertation Fellowship, 1997-1998 Andrew W. Mellon Graduate Fellowship in the Humanities, 1992-1997 (honorary) Scott Prize for Excellence in Slavic (Best Senior Essay in Russian Literature at Yale), 1990 PUBLICATIONS (items with an asterisk were peer-reviewed) “The Troubled Frame Narrative: Bad Listening in Late Imperial Russia,” Russian Review, October 2013 (pp. -

Curriculum Vitae

7/102021 CURRICULUM VITAE Maxim D. Shrayer Professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies Author and literary translator Department of Eastern, Slavic, and German Studies 210 Lyons Hall Boston College Chestnut Hill, MA 02467-3804 USA tel. (617) 552-3911 fax. (617) 552-3913 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.shrayer.com https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/mcas/departments/slavic-eastern/people/faculty- directory/maxim-d--shrayer.html @MaximDShrayer ================================================================== EDUCATION Yale University Ph.D., Russian Literature; minor in Film Studies 1992-1995 Yale University M.A., M.Phil., Russian Literature 1990-1992 Rutgers University M.A., Comparative Literature 1989-1990 Brown University B.A., Comparative Literature 1987-1989 Honors in Literary Translation Moscow University Transferred to Brown University upon 1984-1989 immigrating to the U.S.A. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Boston College Professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies Department of Eastern, courtesy appointment in the English Department since Slavic, and German Studies 2002 Faculty in the Jewish Studies Program since 2005 2003-present teaching Russian, Jewish, and Anglo-American literature, comparative literature, translation studies, and Holocaust studies, at the graduate and undergraduate levels Boston College Associate Professor (with tenure) Department of Slavic and Eastern Languages and Literatures 2000-2003 Boston College Assistant Professor Department of Slavic and Eastern Languages and Literatures 1996-2000 Connecticut College -

Safran CV December 2016

GABRIELLA SAFRAN Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures update 12/16 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2006 650-723-4414 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Stanford University, 1998-2003 Associate Professor, Stanford University, 2003-2010 Full Professor, Stanford University, 2010-present Appointed to Eva Chernov Lokey Chair in Jewish Studies, 2011 EDUCATION Princeton University, Ph.D., Slavic Languages and Literatures, 1998. Dissertation: "Narratives of Jewish acculturation in the Russian Empire: Bogrov, Orzeszkowa, Leskov, Chekhov." Adviser: Caryl Emerson Yale University, B.A., magna cum laude, with honors in Soviet and East European Studies, 1990. Senior Essay: "The descent of the raznochinets literator: Osip Mandelstam's 'Shum vremeni' and evolutionary theory." Adviser: Tomas Venclova FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Stanford Humanities Center, Ellen Andrews Wright Fellowship, 2015-2016 Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences (short-listed), 2011 Jordan Schnitzer Book Award in Jewish Literature and Linguistics (Honorable Mention), 2011 Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies (MLA), 2008 Stanford Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007 Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania, yearlong research fellowship, 2002-2003 Best Book in Literary or Cultural Studies, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (shared), 2002 -

{PDF} a Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus: Probing The

A MARGINAL JEW: RETHINKING THE HISTORICAL JESUS: PROBING THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE PARABLES VOLUME V PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John P. Meier | 464 pages | 02 Feb 2016 | Yale University Press | 9780300211900 | English | New Haven, United States Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume V | Yale University Press Please ensure you're using that browser before attempting to purchase. Description Reviews. Since the late nineteenth century, New Testament scholars have operated on the belief that most, if not all, of the narrative parables in the Synoptic Gospels can be attributed to the historical Jesus. This book challenges that consensus and argues instead that only four parables—those of the Mustard Seed, the Evil Tenants, the Talents, and the Great Supper—can be attributed to the historical Jesus with fair certitude. In this eagerly anticipated fifth volume of A Marginal Jew, John Meier approaches this controversial subject with the same rigor and insight that garnered his earlier volumes praise from such publications as the New York Times and Christianity Today. This seminal volume pushes forward his masterful body of work in his ongoing quest for the historical Jesus. John P. Meier is William K. He has also written six other books and over seventy articles. His remarkable erudition both in the primary sources and in the extensive secondary literature is palpable throughout. He is the very model of a sober and learned contrarian! Yet, with his characteristic wisdom and wit, John Meier guides us through the many parables that are attached to Jesus' name. Freely conceding that in many cases utter certainty will escape us, Meier shows us which parables are most likely from the lips of Jesus and why. -

Shimon Markish

SHIMON MARKISH Russian Jewish Literature after the Second World War and before Perestroika Russian Jewish literature—I use the word literature broadly to cover the whole spectrum from journalism and historiography to poetry and fiction—began in the middle of the nineteenth century. It is unanimously agreed that its ‘founding father’ was Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869), editor and publisher of the first Russian Jewish periodical, the weekly Rassvet [Dawn], published in 1860–61. Let me emphasize that the first Jewish periodical published in Russia appeared neither in Hebrew nor in Yiddish, but in Russian. Rabinovich was the first Jewish prose writer to attract the attention of both the Jewish and the Russian reading public. He used themes and devices which anticipated those found in the classical Yiddish literature of Sholem Aleichem. The appearance and development of Jewish literature written in Russian is closely related to the ideas of the Haskalah. It paralleled the appearance and development of Jewish literature in German in Prussia, the homeland of the Haskalah, and also in Austria. Like the latter, it, too, aimed at the amalgamation of Jews with the majority indigenous population in all things except religion. But at the beginning of the 1880s, Russian Jewish literature had taken the first steps on its own particular path, a path which was later adopted by Jewish literature in other European languages. The great pogroms in the Russian Empire in 1881–82 made most, if not all, of the Maskilim who believed in assimilation rethink their position and become nationalistic, advocating a homeland in Palestine. In the cultural context, this meant a repudiation of their previous hostility to traditional forms of Jewish life and Jewish thought and a new interest in these matters. -

The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature

General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature By Maxim D. Shrayer DUAL LITERARY IDENTITIES What are cultures measured by? Cultural contributions are difficult to quantify and even harder to qualify without a critical judgment in hand. In the case of verbal arts, and of literature specifically, various criteria of formal perfection and originality, significance in literary history, and aspects of time, place, and milieu all contribute to the ways in which one regards a writer’s contribution. In the case of Jewish culture in Diaspora, and specifically of Jewish writing created in non-Jewish languages adopted by Jews, the reckoning of a writer’s status is riddled with a set of powerful contrapositions. Above all else, there is the duality, or multiplicity, of a writer’s own iden- tity—both Jewish and German (Heinrich Heine) or French (Marcel Proust) or Russian (Isaac Babel) or Polish (Julian Tuwim) or Hungarian (Imre Kertész) or Brazilian (Clarice Lispector) or Canadian (Mordechai Richler) or American (Bernard Malamud). Then there is the dividedly redoubled perspec- tive of a Diasporic Jew: both an in-looking outsider and an out-looking insider. And there is the language of writing itself, not always one of the writer’s native setting, not necessarily one in which a writer spoke to his or her own parents or non-Jewish childhood friends, but in some cases a second or third or forth language—acquired, mastered, and made one’s own in a flight from home.1 Evgeny Shklyar (1894–1942), a Jewish-Russian poet and a Lithuanian patriot who translated into Russian the text of the Lithuanian national anthem 1 In the context of Jewish-Russian history and culture, the juxtaposition between a “divided” and a “redoubled” identity goes back to the writings of the critic and polemicist Iosif Bikerman (1867–1941? 1942?), who stated in 1910, on the pages of the St. -

Judaïsme(S) : Genre Et Religion

Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire 44 | 2016 Judaïsme(s) : genre et religion Leora Auslander et Sylvie Steinberg (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/clio/13187 DOI : 10.4000/clio.13187 ISSN : 1777-5299 Éditeur Belin Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2016 ISBN : 9782701198538 ISSN : 1252-7017 Référence électronique Leora Auslander et Sylvie Steinberg (dir.), Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, 44 | 2016, « Judaïsme(s) : genre et religion » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2021, consulté le 07 janvier 2021. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/clio/13187 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/clio.13187 Tous droits réservés CLIO. Femmes, Genre, Histoire 44/2016 Judaïsme(s) : genre et religion Responsables du numéro : Leora AUSLANDER & Sylvie STEINBERG Leora AUSLANDER & Sylvie STEINBERG Éditorial 7 Dossier Christophe BATSCH La mère profanée : retour sur une innovation juridique dans la Judée antique 21 Elisheva BAUMGARTEN Prier à part ? Le genre dans les synagogues ashkénazes médiévales (XIIIe-XIVe siècle) 43 Cristina CIUCU Un messie au féminin ? Mystique juive et messianisme aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles 63 Isabelle LACOUE-LABARTHE L’émergence d’une « conscience féministe » juive. Europe, États-Unis, Palestine (1880-1930) 95 Béatrice de GASQUET « Dépasser l’interdit ». Le châle de prière des femmes en France au XXIe siècle 123 Regards complémentaires Ron NAIWELD Le sacrement du langage et la domination masculine. Le neder dans le judaïsme ancien 147 Lisa ANTEBY-YEMINI De l’Éthiopie à Israël : migration et rôles rituels des femmes Beta Israel 157 4 Leora Auslander & Sylvie Steinberg État de la recherche Sylvie Anne GOLDBERG Lien de sang – lien social. -

Lesson41.Pdf

L e s s o n 41 The Origins of Zionism Outline: 1. Historical background and influences: Emancipation, Enlightenment, nationalism and persecution. 2. Proto Zionists: Rabbi Judah Alklai, Rabbi Tzvi Kalischer, Moshe Hess 3. The first Zionists: Pinsker & Herzl. Introduction: Zionism has changed the face of Judaism and the course of Jewish history. Was the development of Zionism a revolution – a break with all Jewish ideology that went before it, the birth of a new Jew as master of his own destiny? Or, was it a realization of the unbroken loyalty the Jewish people held for their ancestral land? Was it a Jewish manifestation of nineteenth century state nationalism or a yearning for socialist utopia? Or maybe it was just another way to survive? Its origins, like Zionism itself, are complex and varied. In this lesson we will study the different ingredients and personalities that gave rise to modern Zionism and ask ourselves: did Zionism/the State of Israel provide the solutions to the problems its originators envisioned. Goals: 1. Study of Jewish history in the 19th century and the various Jewish responses to the upheavals felt by a changing world. 2. Familiarity with proto-Zionists and some of their writings. 3. Examination of the beginnings of modern Zionism. 4. Discussion of Zionism as a revolution or a culmination and the repercussions of each perception. Expanded Outline: 1: Historical Background and Influences 1. Jews of Western Europe: From the end of the 18th century on more and more countries in Western Europe repealed laws that discriminated against Jews allowing them to enter the general society as equal citizens of their respective countries.