Shimon Markish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

The Anti-Imperial Choice This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Anti-Imperial Choice the Making of the Ukrainian Jew

the anti-imperial choice This page intentionally left blank The Anti-Imperial Choice The Making of the Ukrainian Jew Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern Yale University Press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Ehrhardt type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. The anti-imperial choice : the making of the Ukrainian Jew / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-13731-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Jewish literature—Ukraine— History and criticism. 2. Jews in literature. 3. Ukraine—In literature. 4. Jewish authors—Ukraine. 5. Jews— Ukraine—History— 19th century. 6. Ukraine—Ethnic relations. I. Title. PG2988.J4P48 2009 947.7Ј004924—dc22 2008035520 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent postconsumer waste (PCW) and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). 10987654321 To my wife, Oxana Hanna Petrovsky This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Politics of Names and Places: A Note on Transliteration xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 chapter 1. -

Jewish-Related Scholarship in the Soviet Union, 1953–1967

Gennady Estraikh Sholem Aleichem and Qumran: Jewish-Related Scholarship in the Soviet Union, 1953–1967 The Jewishacademic centers established in the earlySoviet state functionedal- most exclusively in Yiddish and had eclipsed or subdued the remnants of Jewish studies pursued at academic and independent organizations of the pre-1917pe- riod. In Kiev,the most vigorous of the new centers developedultimatelyinto the Institute of JewishProletarian Culture(IJPC), astructural unit of the Ukrainian AcademyofSciences.By1934, the IJPC had on its payroll over seventy people in academic and administrative roles.Two years later,however,the Stalinist purgesofthe time had consumed the IJPC and sent manyofits employees to prison to be later sentenced to death or gulag.¹ In Minsk, the authorities similarly destroyed the academic Institute of National Minorities, which mainlydealt with Jewish-related research.² By this time, all Jewish(in fact,Yiddish-language) ed- ucational institutions,includinguniversity departments, ceased to exist.Some scholars moved to otherfields of research or left academia entirely. Soviet school instruction and culturalactivity in Yiddish emergedinthe territories of Poland, Romania, and the Baltic states,forciblyacquiredin1939and 1940,but after June 22, 1941, all these disappearedinthe smoke of World WarII. However,the IJPC had an afterlife: in the fall of 1936,the authorities permit- ted the formation of asmall academic unit named the Bureau(kabinet)for Re- search on Jewish Literature, Language, and Folklore. The Bureauendured until 1949,when it fell victim to acampaign that targeted the remainingJewish insti- tutions. In the same year,the authorities closed the Lithuanian Jewish Museum, Note: The research for thisarticle wasconductedaspart of the Shvidler Projectfor the History of the Jews in the Soviet Union at New York University. -

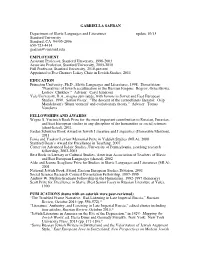

Safran CV for Profile November 2019

GABRIELLA SAFRAN Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures update 11/19 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2006 650-723-4414 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Stanford University, 1998-2003 Associate Professor, Stanford University, 2003-2010 Full Professor, Stanford University, 2010-present Appointed to Eva Chernov Lokey Chair in Jewish Studies, 2011 EDUCATION Princeton University, Ph.D., Slavic Languages and Literatures, 1998. Dissertation: "Narratives of Jewish acculturation in the Russian Empire: Bogrov, Orzeszkowa, Leskov, Chekhov." Adviser: Caryl Emerson Yale University, B.A., magna cum laude, with honors in Soviet and East European Studies, 1990. Senior Essay: "The descent of the raznochinets literator: Osip Mandelstam's 'Shum vremeni' and evolutionary theory." Adviser: Tomas Venclova FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Stanford Humanities Center, Ellen Andrews Wright Fellowship, 2015-2016 Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences (short-listed), 2011 Jordan Schnitzer Book Award in Jewish Literature and Linguistics (Honorable Mention), 2011 Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies (MLA), 2008 Stanford Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007 Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania, yearlong research fellowship, 2002-2003 Best Book in Literary or Cultural Studies, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (shared), 2002 -

2000.03.07. Ceu 1

2000.03.07. CEU 1 SPLIT IN TWO OR DOUBLED? Zsuzsa Hetényi The title is taken from an article by Iosif Bikerman published in 1910.1 There it is presented as a statement (‘not split in two but doubled’), but I shall consider it as a question because the history of Russian Jewish literature is not only a thing of the past: Russian Jewish authors began to ask questions that we continue to ask even today and that we cannot yet answer. My purpose in this paper is threefold: to discuss some theoretical questions, to give a short survey of the 80 years of Russian Jewish literature, and finally to analyse a short story by Lev Lunz. First, I would like to say something about how I arrived at this topic. In 1991 I published a book on Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry,2 a collection of 35 stories based on the writer’s experiences with Budenny’s Cavalry in 1920. The main issue for me was what problems led Babel to this unusual form of self-expression. The most important layer of this cycle of stories is Babel’s duality, which is expressed in various ways. ‘I am an outsider, in long trousers, I don’t belong, I’m all alone’, he writes in his diary of 1920.3 Babel is ambivalent about his Jewishness – he belongs organically to his people and at the same time he finds them repellent. Sometimes he lies to his fellow Jews, hiding his Jewishness. When going to the synagogue, he is moved by the service but unable to follow it in his prayer book. -

Russie-Europe La Fin Du Schisme

Georges Nivat (1993) Russie-Europe La fin du schisme Études littéraires et politiques Parties nos 10 à 20 Un document produit en version numérique par Mme Marcelle Bergeron, bénévole Professeure à la retraite de l’École Dominique-Racine de Chicoutimi, Québec et collaboratrice bénévole Courriel : mailto:[email protected] Dans le cadre de la collection : "Les classiques des sciences sociales" dirigée et fondée par Jean-Marie Tremblay, professeur de sociologie au Cégep de Chicoutimi Site web : http://classiques.uqac.ca/ Une collection développée en collaboration avec la Bibliothèque Paul-Émile-Boulet de l'Université du Québec à Chicoutimi Site web: http://bibliotheque.uqac.uquebec.ca/index.htm Georges Nivat, Russie-Europe, la fin du schisme : parties 10 à 20 (1993) 344 Un document produit en version numérique par Mme Marcelle Bergeron, bénévole, professeure à la retraite de l’École Dominique-Racine de Chicoutimi, Québec. Courriel : mailto:[email protected] À partir de : Georges Nivat. Russie-Europe – La fin du schisme ; Études littéraires et politiques : Lausanne, Suisse : Édition L’Âge d’Homme, 1993, 810 pp. Parties 10 à 20 du livre. M Georges Nivat, historien des idées et slavisant, professeur honoraire, Université de Genève, nous a accordé le 27 mars 2006 son autorisation de diffuser ce livre sur le portail Les Classiques des sciences sociales. Courriel : [email protected] Polices de caractères utilisés : Pour le texte: Times New Roman, 12 points. Pour les citations : Times New Roman, 12 points. Pour les notes de bas de page : Times New Roman, 12 points. Édition électronique réalisée avec le traitement de textes Microsoft Word 2004 pour Macintosh. -

„Idegen Költők” – „Örök Barátaink” Világirodalom a Magyar Kulturális Emlékezetben a Kötet Megjelenését Az OTKA (NK 71770) Támogatta

„idegen költők” – „örök barátaink” Világirodalom a magyar kulturális emlékezetben a kötet megjelenését az OTKA (NK 71770) támogatta. © Szerkesztők, szerzők, 2010 © l’Harmattan kiadó, 2010 l’Harmattan France 7 rue de l’ecole Polytechnique 75005 Paris t.: 33.1.40.46.79.20 l’Harmattan italia SRL Via bava, 3710124 torino-italia t./F.: 011.817.13.88 iSBN a kiadásért felel gyenes ádám. a kiadó kötetei megrendelhetõk, illetve kedvezménnyel megvásárolhatók: l’Harmattan könyvesbolt 1053 budapest, kossuth l. u. 14–16. tel.: 267-5979 [email protected] www.harmattan.hu a borító Ujváry Jenő, a nyomdai előkészítés kállai Zsanett munkája. a nyomdai munkákat a robinco kft. végezte, felelõs vezetõ kecskeméthy Péter. „idegen költők” – „örök barátaink” s Világirodalom a magyar kulturális emlékezetben Szerkesztette gárdos bálint – Péter ágnes – ruttkay – Veronikatimár – andrea budapest, 2010 Tartalom előszó . 7 Pikli natália: Feleselő szavak és asszonyok: a shrew az angol és magyar kulturális emlékezetben . 11 Madarász imre: alfieri Magyarországon . 29 Maráczi géza: „a legkitünőbb genre-író”: dickens hatása az életkép műfajára és a magyar irodalmi újságírás kezdetei . 35 Mácsok Márta: a walesi bárdok értelmezéséhez . 53 Péteri Éva: a viktoriánus kulturális örökség Gulácsy lajos művészetében . 67 isztrayné teplán ágnes: „egy ilyen jó európai és kultúrmisszionárius” Magyarországon . 77 Farkas ákos: Fehérek között egy másik európai . 93 Péter ágnes: Milton a XX. század első felének magyar kulturális emlékezetében . 105 tóth réka: bontakozó titkok: babits Mihály és az angol-amerikai detektívregény . 131 Frank tibor: Thomas Mann: egy európai Magyarországon és az egyesült államokban . 151 gombár Zsófia: brit irodalom Magyarországon és Portugáliában 1949 és 1974 között . 171 Hetényi Zsuzsa: „Csonka” Oroszország? . 191 Paraizs Júlia: „Sándor ezért még hálás lesz nekem a túlvilágon.” . -

Fulfillmenttheep008764mbp.Pdf

FULFILLMENT ^^^Mi^^if" 41" THhODOR HERZL FULFILLMENT: THE EPIC STORY OF ZIONISM BY RUFUS LEARSI The World Publishing Company CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK Published by The World Publishing Company FIRST EDITION HC 1051 Copyright 1951 by Rufus Learsi All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a newspaper or magazine. Manufactured in the United States of America. Design and Typography by Jos. Trautwein. TO ALBENA my wife, who had no small part in the making of this book be'a-havah rabbah FOREWORD MODERN or political Zionism began in 1897 when Theodor Herzl con- vened the First Zionist Congress and reached its culmination in 1948 when the State of Israel was born. In the half century of its career it rose from a parochial enterprise to a conspicuous place on the inter- national arena. History will be explored in vain for a national effort with roots imbedded in a remoter past or charged with more drama and world significance. Something of its uniqueness and grandeur will, the author hopes, flow out to the reader from the pages of this narrative. As a repository of events this book is not as inclusive as the author would have wished, nor does it make mention of all those who labored gallantly for the Zionist cause across the world and in Pal- estine. Within the compass allotted for this work, only the more significant events could be included, and the author can only crave forgiveness from the actors living and dead whose names have been omitted or whose roles have perhaps been understated. -

Safran CV October 2013(1)

GABRIELLA SAFRAN Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures update 10/13 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2006 650-723-4414 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT Assistant Professor, Stanford University, 1998-2003 Associate Professor, Stanford University, 2003-2010 Full Professor, Stanford University, 2010-present Appointed to Eva Chernov Lokey Chair in Jewish Studies, 2011 EDUCATION Princeton University, Ph.D., Slavic Languages and Literatures, 1998. Dissertation: "Narratives of Jewish acculturation in the Russian Empire: Bogrov, Orzeszkowa, Leskov, Chekhov." Adviser: Caryl Emerson Yale University, B.A., magna cum laude, with honors in Soviet and East European Studies, 1990. Senior Essay: "The descent of the raznochinets literator: Osip Mandelstam's 'Shum vremeni' and evolutionary theory." Adviser: Tomas Venclova FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Wayne S. Vucinich Book Prize for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies in any discipline of the humanities or social sciences (short-listed), 2011 Jordan Schnitzer Book Award in Jewish Literature and Linguistics (Honorable Mention), 2011 Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies (MLA), 2008 Stanford Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007 Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania, yearlong research fellowship, 2002-2003 Best Book in Literary or Cultural Studies, American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (shared), 2002 Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures (MLA), 2001 National Jewish Book Award, Eastern European Studies Division, 2001 Social Science Research Council Dissertation Fellowship, 1997-1998 Andrew W. Mellon Graduate Fellowship in the Humanities, 1992-1997 (honorary) Scott Prize for Excellence in Slavic (Best Senior Essay in Russian Literature at Yale), 1990 PUBLICATIONS (items with an asterisk were peer-reviewed) “The Troubled Frame Narrative: Bad Listening in Late Imperial Russia,” Russian Review, October 2013 (pp. -

Il'ja Erenburg: Ein Sowjetischer Schriftsteller Jüdischer Herkunft

FORSCHUNGSSTELLE OSTEUROPA -Bremen- Nr.2 Sowjetunion September 1992 I1'ja Erenburg. Ein sowjetischer Schriftsteller jüdischer Herkunft von Verena Dohrn Auszüge aus zwei Beiträgen zur Geschichte der Juden in der Sowjetunion 1. Shimon Markish: Ilja Erenburg, in: VEK (Vestnik evrejskoj kul'tury), Riga, Nr. 6/1990; 7/1991 2. Boris Paramonov: Portret Evreja: Erenburg, in: Zvezda (Stern), Leningrad, Nr. 1/1991 ~Tt:lLf 0STfv'A()Pb, I Ir 011I ..JM'~1i1'~. to'ef"'" '--1'- -T- C~ Aö"J - ;2; Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen Universitätsallee GW 1, Postfach 33 04 40,2800 Bremen 33 Tel. 0421/218-3687, Fax: 0421/218-3269 1 IL'.JA ERENBURG EIN SOWJETISCHER SCHRIFTSTELLER JÜDISCHER HERKUNFT Es existierten zwei Erenburgs, selten lebten sie in Frieden, oft bedrängte, ja, erdrückte der eine den anderen; es war keine Heuchelei, sondern das schwere Schicksal eines Menschen, der sich ziemlich oft irrte, aber die Idee des Verrätertums füchterlich haßte. Il'ja Erenburg 1964 Zwei Beiträge über Il'ja Erenburg seien in Auszügen vorgestellt, die neben anderen den (damals noch) sowjetischen, russischsprachigen Lesern im vergangenen Jahr, dem einhundertsten Geburtsjahr Erenburgs, dem letzten Lebensjahr der Sowjetunion, zur Lektüre empfohlen wurden. Beide Beiträge setzen sich mit dem jüdischen Erenburg auseinander, einem Aspekt, der in der offiziellen Auseinandersetzung mit dem Schriftsteller, Journalisten und Übersetzer in der Sowjetunion, sei es in der Forschung, sei es im Feuilleton, bis dahin tabu gewesen war. Die Autoren dieser Beiträge sind der russisch-jüdische Altphilologe, Übersetzer und Publizist Shimon Markish (VEK), Genf, und der russische Philosoph und Kulturhistoriker Boris Paramonov (Zvezda), New York. Markish wie Paramonov kommen aus der Sowjetunion, haben dieses Land jedoch bereits seit geraumer Zeit - Markish (*Baku 1931) 1970, Paramonov (*Leningrad 1937) 1977 - verlassen. -

Archives of the Center for Studies in History and Culture of East European Jewry

Archives of the Center for Studies in History and Culture of East European Jewry LIST OF CONTENTS Foreword. Leonid Finberg ......................................................................................................5 І. Archives of the Writers .....................................................................................................13 1. Matvii Talalaievsky .............................................................................................16 2. Natan Zabara ...................................................................................................... 24 3. Oleksandr Lizen ..................................................................................................29 4. Borys Khandros .................................................................................................. 35 5. Ikhil Falikman .................................................................................................... 38 6. Dora Khaikina..................................................................................................... 42 7. Ryva Baliasna ......................................................................................................46 8. Isaak Kipnis .........................................................................................................49 9. Mykhailo Pinchevsky ......................................................................................... 53 10. Yosyp Bukhbinder............................................................................................. 58 -

Ñîäåðæàíèå Contents

Ab Imperio, 1/2005 òåìà ãîäà 2005 annual theme: ßÇÛÊÈ ÑÀÌÎÎÏÈÑÀÍÈß ÈÌÏÅÐÈÈ È ÌÍÎÃÎÍÀÖÈÎÍÀËÜÍÎÃÎ ÃÎÑÓÄÀÐÑÒÂÀ LANGUAGES OF SELF-DESCRIPTION IN EMPIRE AND MULTINATIONAL STATE Ñîäåðæàíèå Contents ÈÌÏÅÐÈß: ËÅÊÑÈÊÀ ÏÐÀÊÒÈÊÈ È ÃÐÀÌÌÀÒÈÊÀ ÀÍÀËÈÇÀ EMPIRE: THE LEXICON OF PRAXIS AND THE GRAMMAR OF ANALYSIS ÌÅÒÎÄÎËÎÃÈß È ÒÅÎÐÈß I. METHODOLOGY AND THEORY 10 Îò ðåäàêöèè ßçûêè ñàìîîïèñàíèÿ èìïåðèè è íàöèè êàê èññëåäî- âàòåëüñêàÿ ïðîáëåìà è ïîëèòè÷åñêàÿ äèëåììà 11 From the Editors Languages of Self-Description of Empire and Nation as a Research Problem and a Political Dilemma 23 I. Gerasimov, S. Glebov, A. Kaplunovski, M. Mogilner, A. Semyonov In Search of New Imperial History 33 È. Ãåðàñèìîâ, Ñ. Ãëåáîâ, À. Êàïëóíîâñêèé, Ì. Ìîãèëüíåð, À. Ñåì¸íîâ  ïîèñêàõ íîâîé èìïåðñêîé èñòîðèè Àëåêñàíäð Êàìåíñêèé Íåêîòîðûå êîììåíòàðèè ê ðåäàêöèîííîìó ïðåäèñëîâèþ  ïîèñêàõ íîâîé èìïåðñêîé èñòîðèè 57 Alexander Kamenskii Some Comments on the Foreword to New Imperial History Alan Sked Empire: A Few Thoughts 65 Àëàí Ñêåä Èìïåðèÿ: íåêîòîðûå ðàçìûøëåíèÿ Richard T. Chu The New Imperial History and U.S. Imperialism 69 Ðè÷àðä ×ó Íîâàÿ èìïåðñêàÿ èñòîðèÿ è èìïåðèàëèçì ÑØÀ 3 Ñîäåðæàíèå/Contents Äîìèíèê Ëèâåí Èìïåðèÿ, èñòîðèÿ è ñîâðåìåííûé ìèðîâîé ïîðÿäîê 75 Dominic Lieven Empire, History, and the Contemporary Global Order Interview with Anthony Pagden There Is a Real Problem with the Semantic Field of Empire 117 Èíòåðâüþ ñ Ýíòîíè Ïàãäåíîì Ñ ñåìàíòè÷åñêèì ïîëåì èìïåðèè ñóùåñòâóåò ðåàëüíàÿ ïðîáëåìà ÈÑÒÎÐÈß II. HISTORY 136 Marina Mogilner On Cabbages, Kings, and Jews (Yuri Slezkine. The Jewish Century. Princeton, 2004; Yu. Selzkine. Era Merkuriia: evrei v sovre- mennom mire. Moskva, 2005) 137 Ìàðèíà Ìîãèëüíåð Î êîðîëÿõ, êàïóñòå è åâðåÿõ (Yuri Slezkine.