January 27, 2020 Via Web [

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Crayfishes of the Genus Orconectes Section Limosus (Crustacea: Decopoda)

THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE Vol. 62 MARCH, 1962 No. 2 THE EVOLUTION OF CRAYFISHES OF THE GENUS ORCONECTES SECTION LIMOSUS (CRUSTACEA: DECOPODA) RENDELL RHOADES Department of Zoology and Entomology, The Ohio State University, Columbus 10 The earliest described crayfish species now included in the Section limosus of the Genus Orconectes was described by Samuel Constantine Rafinesque (1817: 42). He reported the species, which he named Astacus limosus, "in the muddy banks of the Delaware, near Philadelphia." How ironical it now seems, that when Rafinesque located at Transylvania three years later and traveled to Henderson, Kentucky, to visit a fellow naturalist, John J. Audubon, he could have collected from the streams of western Kentucky a crayfish that he might have identified as the species he had described from the Delaware. We now know that these streams of the knobstone and pennyroyal uplands are the home of parent stock of this group. Moreover, this parental population on the Cumberland Plateau is now separated from Rafinesque's Orconectes limosus of the Atlantic drainage by more than 500 miles of mountainous terrain. Even Rafinesque, with his flair for accuracy and vivid imagination, would have been taxed to explain this wide separation had he known it. A decade after the death of Rafinesque, Dr. W. T. Craige received a blind crayfish from Mammoth Cave. An announcement of the new crayfish, identi- fied as "Astacus bartonii (?)" appeared in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia (1842: 174-175). Within two years the impact of Dr. Craige's announcement was evidenced by numerous popular articles both here and abroad. -

Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1 Justin Augustine (CA Bar No. 235561) Jaclyn Lopez (CA Bar No. 258589) 2 Center for Biological Diversity 351 California Street, Suite 600 3 San Francisco, CA 94104 Tel: (415) 436-9682 4 Fax: (415) 436-9683 [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Collette L. Adkins Giese (MN Bar No. 035059X)* Center for Biological Diversity 8640 Coral Sea Street Northeast 7 Minneapolis, MN 55449-5600 Tel: (651) 955-3821 8 Fax: (415) 436-9683 [email protected] 9 Michael W. Graf (CA Bar No. 136172) 10 Law Offices 227 Behrens Street 11 El Cerrito, CA 94530 Tel: (510) 525-7222 12 Fax: (510) 525-1208 [email protected] 13 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Center for Biological Diversity and 14 Pesticide Action Network North America *Seeking admission pro hac vice 15 16 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 17 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 18 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 19 20 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL ) 21 DIVERSITY, a non-profit organization; and ) Case No.__________________ PESTICIDE ACTION NETWORK ) 22 NORTH AMERICA, a non-profit ) organization; ) 23 ) Plaintiffs, ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY 24 ) AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF v. ) 25 ) ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ) 26 AGENCY; and LISA JACKSON, ) Administrator, U.S. EPA; ) 27 ) Defendants. ) 28 _____________________________________ ) Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief 1 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1. This action challenges the failure of Defendants Environmental Protection Agency and 3 Lisa Jackson, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, (collectively “EPA”) to consult with the 4 United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”) and National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS”) 5 (collectively “Service”) pursuant to Section 7(a)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. -

Crayfish News Volume 32 Issue 1-2: Page 1

June 2010 Volume 32, Issue 1-2 ISSN: 1023-8174 (print), 2150-9239 (online) The Official Newsletter of the International Association of Astacology Inside this issue: Cover Story 1 Searching for Crayfish in the President’s Corner 2 River Bug, Ukraine Info About IAA18 3 Future Directions 4 Symposium Info Short Articles 6 Male Form 6 Alternation in Spinycheek Crayfish, Orconectes limosus, at Cessy (East-central France): The Discovery of Anomalous Form Males IAA Related News 10 News Items From 11 Around the World Meeting 13 Announcements Literature of 16 Interest to Astacologists Figure 1. Astacus leptodactylus from the River Bug, Ukraine. comparison with other species, information n official opportunity for the author on A. pachypus is very limited (Souty-Grosset A to travel to the Ukraine was the 2nd et al., 2006). Since no specimens were meeting of the signatories to the available to be photographed for the “Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on identification guide of crayfish species in the Conservation and Management of the Europe (Pöckl et al., 2006), only a sketch was middle European population of the Great presented. Bustard (Otis tarda)” under the “Convention Feodosia, located on the Crimean of Migratory Species of Wild Animals” (CMS th Peninsula, is not easily reached by airplane, or Bonn Convention) from November 8-12 with the nearest airport being in Simferopol. 2008. There are no direct flights to this region from The author has always dreamed of most European capitals, with connecting visiting the Ukraine in order to collect flights running through Kiev, Moscow or specimens of the thick-clawed crayfish, Istanbul. -

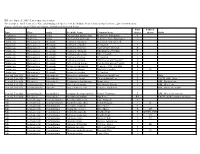

Threatened and Endangered Species List

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

Literature Cited for Nashville Crayfish

LITERATURE CITED FOR NASHVILLE CRAYFISH Acquistapace, P., L. Aquiloni, B.A. Hazlett and F. Gherardi. 2002. Multimodal communication in crayfish: sex recognition during mate search by male Austropotamobius pallipes. Can. J. Zool. 80:2041–2045. 10.1139/z02-171. Barrociere, L.J. 1986. The ecological assessment and distribution status of the Nashville Crayfish, Orconectes shoupi. Masters Thesis, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, TN. 54pp with appendices. Bergey, E.A., S.N. Jones and D.B. Fenolio. 2005. Surveys and Studies of the Oklahoma Crayfish and the Grotto Salamander. Final Report. Oklahoma Biological Survey. The University of Oklahoma. 26 pp, including appendix. Bouchard, R.W. 1976. Investigations on the conservation status of freshwater decapod crustaceans in the United States. Part II: Eastern North American Crayfish. Office of Endangered Species, U.S. Department of the Interior. 26pp. Bouchard, R.W. 1984. Distribution and status of the endangered crayfish Orconectes shoupi (Decapoda: Cambaridae). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tennessee Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Tennessee. 25pp. Boyd Center for Business and Economic Research. 2015. University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN. Accessed 9/6/2017 <http://cber.haslam.utk.edu/popproj.htm> Carpenter 2004. 7 September 2004 email to David Withers (DNH) concerning occurrence of Nashville crayfish (Orconectes shoupi) in Collins Creek, Nashville, Davidson County, TN, 2 pp. Carpenter, J. 2002. Density and Distribution of the Nashville Crayfish in the Mill Creek Drainage Basin. Biology Department, David Lipscomb University, Nashville, TN. Submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Cookeville, Tennessee. 41pp. Cook, S.B. and C.F. Walton. 2008. Habitat characterization of the Nashville crayfish (Orconectes shoupi) in Mill Creek watershed, Tennessee. -

Conservation

CONSERVATION ecapod crustaceans in the families Astacidae, recreational and commercial bait fisheries, and serve as a Cambaridae, and Parastacidae, commonly known profitable and popular food resource. Crayfishes often make as crayfishes or crawfishes, are native inhabitants up a large proportion of the biomass produced in aquatic of freshwater ecosystems on every continent systems (Rabeni 1992; Griffith et al. 1994). In streams, sport except Africa and Antarctica. Although nearly worldwide fishes such as sunfishes and basses (family Centrarchidae) in distribution, crayfishes exhibit the highest diversity in may consume up to two-thirds of the annual production of North America north of Mexico with 338 recognized taxa crayfishes, and as such, crayfishes often comprise critical (308 species and 30 subspecies). Mirroring continental pat- food resources for these fishes (Probst et al. 1984; Roell and terns of freshwater fishes (Warren and Burr 1994) and fresh- Orth 1993). Crayfishes also contribute to the maintenance of water mussels (J. D. Williams et al. 1993), the southeastern food webs by processing vegetation and leaf litter (Huryn United States harbors the highest number of crayfish species. and Wallace 1987; Griffith et al. 1994), which increases avail- Crayfishes are a significant component of aquatic ecosys- ability of nutrients and organic matter to other organisms. tems. They facilitate important ecological processes, sustain In some rivers, bait fisheries for crayfishes constitute an Christopher A. Taylor and Melvin L. Warren, Jr. are cochairs of the Crayfish Subcommittee of the AFS Endangered Species Committee. They can be contacted at the Illinois Natural History Survey, Center for Biodiversity, 607 E. Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820, and U.S. -

TVA JUN 2014 Solar PEA.Pdf

Document Type: EA-Administrative Record Index Field: Environmental Document Transmitted Public/Agencies Project Name: TVA Solar Photovoltaic Projects Project Number: 2013-34 TVA SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAIC PROJECTS DRAFT PROGRAMMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia Prepared by: TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Knoxville, Tennessee June 2014 To request further information, contact: James F. Williamson NEPA Compliance Tennessee Valley Authority 400 West Summit Hill Drive, WT11 D Knoxville, TN 37902 Phone: 865.632.6418 Fax: 865.632.3451 E-mail: [email protected] This page intentionally left blank Contents Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 – PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION ......................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose and Need ................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Background .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Decision to be Made ................................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Related Environmental Reviews and Consultation Requirements .......................................... 4 1.6 Scope of the Programmatic Environmental Assessment ........................................................ -

Tennessee Natural Heritage Program Rare Species Observations for Tennessee Counties 2009

Tennessee Natural Heritage Program Rare Species Observations For Tennessee Counties This document provides lists of rare species known to occur within each of Tennessee's counties. If you are viewing the list in its original digital format and you have an internet connection, you may click the scientific names to search the NatureServe Explorer Encyclopedia of Life for more detailed species information. The following lists were last updated in July 2009 and are based on rare species observations stored in the Tennessee Natural Heritage Biotics Database maintained by the TDEC Natural Heritage Program. For definitions of ranks and protective status, or for instructions on obtaining a site specific project review, please visit our website: http://state.tn.us/environment/na/data.shtml If you need assistance using the lists or interpreting data, feel free to contact us: Natural Heritage Program Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation 7th Floor L&C Annex 401 Church Street Nashville, Tennessee 37243 (615) 532-0431 The lists provided are intended for use as planning tools. Because many areas of the state have not been searched for rare species, the lists should not be used to determine the absence of rare species. The lists are best used in conjunction with field visits to identify the types of rare species habitat that may be present at a given location. For projects that are located near county boundaries or are in areas of the state that have been under-surveyed (particularly in western Tennessee), we recommend that you check rare species lists for adjacent counties or watersheds as well. -

Fisheries Conservation Status of Crayfish Species Paddlefish Conservation Case Study

VOL 32 NO 8 AUGUST 2007 Fish News Legislative Update Journal Highlights FisheriesFisheries Calendar American Fisheries Society • www.fisheries.org Job Center Conservation Status of Crayfish Species Paddlefish Conservation Case Study Fisheries • VOL 32 NO 8 • AUGUST 2007 • WWW.FISHERIES.ORG 365 Northwest Marine Tcchnology, Inc. 366 Fisheries • VOL 32 NO 8 • AUGUST 2007 • WWW.FISHERIES.ORG VOL 32 NO 8 AUGUST 2007 372 AMERIFisheriescan FIshERIES SOCIETY • WWW.FIshERIES.ORG EDitOriaL / SUbsCriPtiON / CirCULatiON OffiCES 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110 • Bethesda, MD 20814-2199 301/897-8616 • fax 301/897-8096 • [email protected] The American Fisheries Society (AFS), founded in 1870, is the oldest and largest professional society representing fisheries scientists. The AFS promotes scientific research and enlightened management of aquatic resources 390 for optimum use and enjoyment by the public. It also XXX encourages comprehensive education of fisheries scientists and continuing on-the-job training. AFS OFFICERS FISHERIES EDITORS Contents STAFF PRESIDENT SENIOR EDITOR SCIENCE Jennifer L. Nielsen Ghassan “Gus” N. EDITORS COLUMN: COLUMN: PRESIDENT ElECT Rassam Madeleine 368 PRESIDENT’S HOOK 398 GUEST DIRECTOR’S LINE Mary C. Fabrizio DIRECTOR OF Hall-Arber New Features for AFS Publications FIRST PUBLICATIONS Ken Ashley Thanks for an Incredible Year VICE PRESIDENT Aaron Lerner Doug Beard As part of an ongoing effort to make AFS William G. Franzin MANAGING Ken Currens Through commitment and hardwork the AFS publications more and more useful for fisheries SECOND EDITOR William E. Kelso volunteer membership has accomplished professionals, several new features have been VICE PRESIDENT Beth Beard Deirdre M. Kimball Donald C. Jackson PRODUCTION Robert T. -

Draft Environmental Assessment for Listing 10 Freshwater Fish and 1 Crayfish As Injurious Wildlife Under the Lacey Act

Draft Environmental Assessment For Listing 10 Freshwater Fish and 1 Crayfish As Injurious Wildlife under the Lacey Act Crucian carp (Carassius carassius), Eurasian minnow (Phoxinus phoxinus), Prussian carp (Carassius gibelio), roach (Rutilus rutilus), stone moroko (Pseudorasbora parva), Nile perch (Lates niloticus), Amur sleeper (Perccottus glenii), European perch (Perca fluviatilis), zander (Sander lucioperca), wels catfish (Silurus glanis), and common yabby (Cherax destructor) Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Branch of Aquatic Invasive Species 5275 Leesburg Pike, MS-FAC Falls Church, VA 22041 September 2015 1 Table of Contents 1) Purpose for the Action .............................................................................................................................. 3 2) Need For Proposed Action ........................................................................................................................ 3 3) Decisions that Need to be Made .............................................................................................................. 4 4) Background ............................................................................................................................................... 4 5) Public Involvement ................................................................................................................................... 8 6) Peer Review ............................................................................................................................................. -

Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Draft Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan for the Nashville Crayfish (Faxonius shoupi) Photo by: Michelle Barbero, Metro Water Services Photo courtesy of Ron Caldwell, Lincoln Memorial University Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Tennessee Ecological Services Field Office Cookeville, Tennessee XX 2019 Draft Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan for the Nashville Crayfish (Faxonius shoupi) XX 2019 Acknowledgements: The Draft Post-delisting Monitoring Plan for the Nashville crayfish was prepared by biologists of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Steve Alexander, Tennessee Ecological Services Field Office). We wish to acknowledge assistance that we received in preparing this plan from the Nashville Zoo and Tennessee Division of Natural Areas. Recommended Citation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Draft Post-delisting Monitoring Plan for the Nashville Crayfish (Faxonius shoupi). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tennessee Ecological Services Field Office, Cookeville, Tennessee. 19 pp. Table of Contents I. Summary of Cooperators Roles in the Post-Delisting Monitoring Planning Effort ............. 3 II. Summary of Species Status at Time of Delisting ................................................................. 3 A. Demographic Parameters ............................................................................................... 3 B. Discussion of Populations .............................................................................................. 4 C. Residual Threats ............................................................................................................ -

A Reassessment of the Conservation Status of Crayfishes of the United States and Canada After 10+ Years of Increased Awareness Christopher A

This article was downloaded by: [Institutional Subscription Access] On: 28 July 2011, At: 08:27 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Fisheries Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufsh20 A Reassessment of the Conservation Status of Crayfishes of the United States and Canada after 10+ Years of Increased Awareness Christopher A. Taylor, Guenter A. Schuster, John E. Cooper, Robert J. DiStefano, Arnold G. Eversole, Premek Hamr, Horton H. Hobbs III, Henry W. Robison, Christopher E. Skelton & Roger F. Thoma Available online: 09 Jan 2011 To cite this article: Christopher A. Taylor, Guenter A. Schuster, John E. Cooper, Robert J. DiStefano, Arnold G. Eversole, Premek Hamr, Horton H. Hobbs III, Henry W. Robison, Christopher E. Skelton & Roger F. Thoma (2007): A Reassessment of the Conservation Status of Crayfishes of the United States and Canada after 10+ Years of Increased Awareness, Fisheries, 32:8, 372-389 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446(2007)32[372:AROTCS]2.0.CO;2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date.