Johnston County Natural Resource Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5635/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0009-ff09e21000-fxes11190900000-167-75635.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-21478, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Domestic and Foreign Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notification of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of review. SUMMARY: In this candidate notice of review (CNOR), we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), present an updated list of plant and animal species that we regard as candidates for or have proposed for addition to the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. Identification of candidate species can assist environmental planning efforts by providing advance notice of potential listings, and by allowing landowners and resource managers to alleviate threats and thereby possibly remove the need to list species as endangered or threatened. Even if we subsequently list a candidate species, the early notice provided here could result in more options for species management and recovery by prompting earlier candidate conservation measures to alleviate threats to the species. This document also includes our findings on resubmitted petitions and describes our 1 progress in revising the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (Lists) during the period October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2018. -

Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 0028 Autor(en)/Author(s): Yefremova Zoya A., Ebrahimi Ebrahim, Yegorenkova Ekaterina Artikel/Article: The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 25: 321-356 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) Zoya YEFREMOVA, Ebrahim EBRAHIMI & Ekaterina YEGORENKOVA Abstract This paper reflects the current degree of research of Eulophidae and their hosts in Iran. A list of the species from Iran belonging to the subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae is presented. In the present work 47 species from 22 genera are recorded from Iran. Two species (Cirrospilus scapus sp. nov. and Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) are described as new. A list of 45 host-parasitoid associations in Iran and keys to Iranian species of three genera (Cirrospilus, Diglyphus and Aprostocetus) are included. Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel zeigt den derzeitigen Untersuchungsstand an eulophiden Wespen und ihrer Wirte im Iran. Eine Liste der für den Iran festgestellten Arten der Unterfamilien Eu- lophinae, Entedoninae und Tetrastichinae wird präsentiert. Mit vorliegender Arbeit werden 47 Arten in 22 Gattungen aus dem Iran nachgewiesen. Zwei neue Arten (Cirrospilus sca- pus sp. nov. und Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) werden beschrieben. Eine Liste von 45 Wirts- und Parasitoid-Beziehungen im Iran und ein Schlüssel für 3 Gattungen (Cirro- spilus, Diglyphus und Aprostocetus) sind in der Arbeit enthalten. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 1992 Band/Volume: Supp_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Baixeras Joaquin, Dominguez Martin Artikel/Article: Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) 97-102 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Proc. VIL Congr. Eur. Lepid., Lunz 3-8.IX.1990 Nota lepid. Supplement No. 4 : 97-102 ; 30.XI.1992 ISSN 0342-7536 Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) Joaquin Baixeras & Martin Dominguez, Dpt. Biologia Animal, Bio- logia Cellular i Parasitologia, Universität de Valencia, C/Dr. Moliner, 50. E-46100 Burjassot (Valencia), Spain. Summary Some remarks are given on two species of the family Tortricidae in Spain with particular reference to the fauna of the Iberian Mountains : Selania resedana Obr. and Rhyacionia piniana H.-S. are recorded for the first time from the Iberian Peninsula. Information about their distribution, taxonomy and variability is given. Selania resedana (Obraztsov, 1959) Laspeyresia resedana Obraztsov, 1959, Tijdschr. Ent., 102 : 186, 196-197, figs. 44, 45. Locus typicus : Savona (Liguria, Italia). Selania resedana : Danilevsky & Kuznetsov, 1969, Fauna USSR, Lepidop- tera, 5 (1) : 448-449, fig. 322. Kuznetsov, in Medvedev, 1978, Opredelitel Nasek. 4 (1) : 647, 680, figs. 557 (3), 585 (3). Diakonoff, 1983, Fauna of Saudi Arabia 5 : 256-258, figs. 27-32. 1984- Material examined : Calles, 1984-85, 203 <$<$, 55 ÇÇ Porta-Coeli, 85, 48 33, 33 99. Titaguas, 3 33, 1 9. All the localities in the province of Valencia (Spain). -

Southern Forest Experiment Station Notes on the Life

w ~ r--.~·-OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 45 APRIL 2, 1935 ~ (Reissue, Feb. 19, 1941) ~ I SOUTHERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION ~ ~ E. L. Demmon, Director l\c,, New Orleans, La. NOTES ON THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE NANTUCKET TIP MO'l'H RHYAOIONIA FRUSTRANA COMST. IN SOUTHEASTERN LOUISlANA By Philip C. Wakeley, Associate Silviculturist Southern Forest Experiment Station ...• I The Occasional Papers of the Southern Forest Experiment Station present information on current southern forestry prob lems under investigation at the station. In some cases, these •contributions were first presented as addresses to a limited i group of people, and as "occasional papers 11 they can reach a " much wider audience, In other cases, they are summaries of investigations prepared especially t o give a report of the progress made in a particular field of research. In any case, the statements herein contained should be considered subject to correction or modification as f urther data are obtained. Note: Assistance in the duplication of this paper was furnished by the personnel of Work Projects Administration official project 165-2-64-102. NOTES ON THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE NANTUCKET TIP MOTH RHYACIONIA FRUSTRANA COMST. IN SOUTHEASTERN LOUISIANAY By Philip C. Wakeley, Associate Silviculturist Southern Forest Experiment Station The Nantucket tip moth (RhYacionia frustrana Comst.) is a small tor tricid moth occurring generally throughout the pine forests of North America. The larvae are responsible for an immense amount of dam~ge to small pines, both in natural reproduction and in planted stands OJ .9 In 1915, W.R. Mattoon, of the United States Forest Service, described the conspicuous damage of the Nantucket tip moth on shortleaf pine (Pinus e'china.ta) in the South (2), but somewhat underrated the potentialities of the insect for mischief. -

Pheromone-Based Disruption of Eucosma Sonomana and Rhyacionia Zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Using Aerially Applied Microencapsulated Pheromone1

361 Pheromone-based disruption of Eucosma sonomana and Rhyacionia zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) using aerially applied microencapsulated pheromone1 Nancy E. Gillette, John D. Stein, Donald R. Owen, Jeffrey N. Webster, and Sylvia R. Mori Abstract: Two aerial applications of microencapsulated pheromone were conducted on five 20.2 ha plots to disrupt western pine shoot borer (Eucosma sonomana Kearfott) and ponderosa pine tip moth (Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott); Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) orientation to pheromones and oviposition in ponderosa pine plantations in 2002 and 2004. The first application was made at 29.6 g active ingredient (AI)/ha, and the second at 59.3 g AI/ha. Baited sentinel traps were used to assess disruption of orientation by both moth species toward pheromones, and E. sonomana infes- tation levels were tallied from 2001 to 2004. Treatments disrupted orientation by both species for several weeks, with the first lasting 35 days and the second for 75 days. Both applications reduced infestation by E. sonomana,but the lower application rate provided greater absolute reduction, perhaps because prior infestation levels were higher in 2002 than in 2004. Infestations in treated plots were reduced by two-thirds in both years, suggesting that while increas- ing the application rate may prolong disruption, it may not provide greater proportional efficacy in terms of tree pro- tection. The incidence of infestations even in plots with complete disruption suggests that treatments missed some early emerging females or that mated females immigrated into treated plots; thus operational testing should be timed earlier in the season and should comprise much larger plots. In both years, moths emerged earlier than reported pre- viously, indicating that disruption programs should account for warmer climates in timing of applications. -

Alabama Forestry Invitational State Manual & Study Guide

Alabama Forestry Invitational State Manual & Study Guide The Alabama Cooperative Extension System (Alabama A&M University and Auburn University) is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Everyone is welcome! Please let us know if you have accessibility needs. © 2020 by the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. All rights reserved. www.aces.edu 4HYD-2426 Alabama Cooperative Extension System Mission Statement The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, the primary outreach organization for the land grant mission of Alabama A&M University and Auburn University, delivers research-based educational programs that enable people to improve their quality of life and economic well-being. ALABAMA 4-H VISION Alabama 4-H is an innovative, responsive leader in developing youth to be productive citizens and leaders in a complex and dynamic society. Our vision is supported through the collaborative, committed efforts of Extension professionals, youth, and volunteers. ALABAMA 4-H MISSION 4-H is the youth development component of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. 4-H helps young people from rural and urban areas explore their interests and expand their awareness of our world while providing opportunities to develop a greater sense of who they are and who they can become–as contributing citizens of our communities, our state, our nation, and our world. This mission is achieved through research-based educational programs of Alabama A&M and Auburn Universities and an ongoing tradition of applied, hands-on/minds-on experiences, which develop the heads, hearts, hands, and health of Alabama youth. 4-H is a community of young people across Alabama who are learning leadership, citizenship, and life skills. -

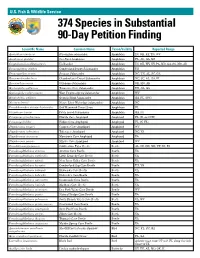

374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding Scientific Name Common Name Taxon/Validity Reported Range Ambystoma barbouri Streamside salamander Amphibian IN, OH, KY, TN, WV Amphiuma pholeter One-Toed Amphiuma Amphibian FL, AL, GA, MS Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Hellbender Amphibian IN, OH, WV, NY, PA, MD, GA, SC, MO, AR Desmognathus abditus Cumberland Dusky Salamander Amphibian TN Desmognathus aeneus Seepage Salamander Amphibian NC, TN, AL, SC, GA Eurycea chamberlaini Chamberlain's Dwarf Salamander Amphibian NC, SC, AL, GA, FL Eurycea tynerensis Oklahoma Salamander Amphibian OK, MO, AR Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander Amphibian TN, AL, GA Gyrinophilus subterraneus West Virginia Spring Salamander Amphibian WV Haideotriton wallacei Georgia Blind Salamander Amphibian GA, FL (NW) Necturus lewisi Neuse River Waterdog (salamander) Amphibian NC Pseudobranchus striatus lustricolus Gulf Hammock Dwarf Siren Amphibian FL Urspelerpes brucei Patch-nosed Salamander Amphibian GA, SC Crangonyx grandimanus Florida Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. and NW) Crangonyx hobbsi Hobb's Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. FL) Stygobromus cooperi Cooper's Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Stygobromus indentatus Tidewater Amphipod Amphipod NC, VA Stygobromus morrisoni Morrison's Cave Amphipod Amphipod VA Stygobromus parvus Minute Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Cicindela marginipennis Cobblestone Tiger Beetle Beetle AL, IN, OH, NH, VT, NJ, PA Pseudanophthalmus avernus Avernus Cave Beetle Beetle VA Pseudanophthalmus cordicollis Little -

Nantucket Pine Tip Moth, Rhyacionia Frustrana, Lures and Traps: What Is the Optimum Combination?

NANTUCKET PINE TIP MOTH, RHYACIONIA FRUSTRANA, LURES AND TRAPS: WHAT IS THE OPTIMUM COMBINATION? Gary L. DeBarr, J. Wayne Brewer, R. Scott Cameron and C. Wayne Berisford' Abstract--Pheromone traps are used to monitor flight activity of male Nantucket pine tip moths, Rhyacionia frustrana (Comstock), to initialize spray timing models, determine activity periods, or detect population trends. However, a standard- ized trapping procedure has not been developed. The relative efficacies of six types of lures and eight commercial phero- mone traps were compared in field tests in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia. Additional factors, including trap color, lure longevity and loading rates and ratios were also tested. These tests demonstrate that lures and1 or traps have a pronounced effect on male moth catches. The Pherocon 1Cwing trap was the most effective. White traps were slightly better than colored traps. Pherocon 1C@wing traps baited with commercial Scent@, EcogenQor Tr6ckQ lures caught the greatest numbers of moths. INTRODUCTION also lower during later tip moth generations even though populations are high (Asaro and Berisford 2001 a). Female NPTM Sex Pheromones and Male Response The Pheromones Larvae of the Nantucket pine tip moth (NPTM), Rhyacionia NPTM females produce a two-component sex pheromone frustrana (Comstock), bore into and kill the shoots of loblolly (Berisford and Brady 1973) and their pheromone glands pine, Pinus taeda L.(Yates 1960). NPTM mate shortly after contain only about 20 nanograms (ng) of attractive they emerge from infested shoots. Female moths produce components. Hill and others (1981) identified a straight- small quantities of sex pheromones that attract conspecific chain 12 carbon monoene acetate, (E)- 9-dodecen-I-yl males for mating (Manley and Farrier 1969). -

The Parasites of the V Nantucket Pine Tip Moth

I I '/' ,. l TECHNICAL BULLETIN 1017 ;\ ~· ., f ,,.-;...__.,I • I V I J r·1,- •..-! . /1 I • • .f '' t : ..... I THE PARASITES OF THE V ;'.,.~ /~ ', ' ( NANTUCKET PINE TIP MOTH J • IN SOUTH CAROLINA ,//1 f~ ) ' R. D. EIKENBARY and RICHARD C. FOX SOUTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION ' CLEMSON UNIVERSITY CLEMSON, SOUTH CAROLINA W. H. WILEY 0, B. GARRISON Dean of Agriculture and Director of Agric ultural Experiment Station Biologi ca l Sciences and Agricultural Research TECHNICAL BULLETIN 1017 JULY 1965 THE PARASITES OF THE NANTUCKET PINE TIP MOTH IN SOUTH CAROLINA R. D. EIKENBARY and RICHARD C. FOX SOUTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION CLEMSON UNIVERSITY CLEMSON, SOUTH CAROLINA W. H. WILEY 0. B. GARRISON Dean of Agriculture and Director of Agricultural Experiment Station Biological Sciences and Agricultural Research SUMMARY A statewide survey of the parasites of the Nantucket pine tip moth, Rhyacionia frustrana ( Comstock), was made by collecting infested pine tips from 23 locations in South Carolina over a 2-year period. Parasites were allowed to emerge in specially designed cages, were identified, and recorded. A total of 37 species of para sites was recovered, all hymenopterous except one dipterous species. Of these, the iclmeumonid, Campoplex frustranac Cushman, was the most abundant with the tachinid, Lixophaga mcdiocris Aldrich, following closely in numbers. Parasitism by locations was shown and comparative parasitism by the two main parasites was listed. It was shown that Campoplex frustrmwc was the most abundant parasite in the Piedmont region and that Lixophaga mcdiocris was the most prevalent in the Coastal Plain region. No definite pattern of dominance could be shown in the Sandhills. -

![El Género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] En La Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9296/el-g%C3%A9nero-rhyacionia-h%C3%BCbner-1825-en-la-pen%C3%ADnsula-ib%C3%A9rica-lepid%C3%B3ptera-tortricidae-1569296.webp)

El Género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] En La Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae)

Bol. San. Veg. Plagas, 22: 711-730, 1996 El género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] en la Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae) J. BAIXERAS, M. DOMÍNGUEZ y S. MARTÍNEZ El género Rhyacionia se encuentra representado en la Península Ibérica por seis especies. Cuatro de ellas constituyen uno de los conjuntos más importantes de especies plaga desde el punto de vista forestal, debido a los daños que causan a especies de Pinus L.. Se trata de R. buoliana, R. pinicolana, R. pinivorana y R. duplana. Estas cuatro especies llegan a ser muy comunes en nuestro territorio. Las otras dos especies del género son menos conocidas. R. maritimana, estrechamente emparentada con R. pini- vorana, es una especie común en las zonas más bajas del Sistema Ibérico pero la infor- mación existente sobre ella es todavía escasa. La última especie que se trata, R. pinia- na U.S., es la de menor tamaño y su biología es completamente desconocida, su geni- talia es drásticamente diferente de las del resto del género y su presencia en la Península se ha detectado muy recientemente. A pesar de su importancia económica, continúa existiendo cierta confusión en la dis- tinción de las especies del género. En este artículo se muestran conjuntamente por pri- mera vez las diferencias taxonómicas entre los adultos de estas seis especies, haciendo especial referencia a la diferenciación genital. J. BAIXERAS; M. DOMÍNGUEZ; S. MARTÍNEZ. Departamento de Biología Animal. Universidad de Valencia. Calle Dr. Moliner 50.46100 Burjassot (Valencia) Palabras clave: Tortricidae, Olethreutinae, Eucosmini, Rhyacionia, Península Ibérica. INTRODUCCIÓN La larva de primer estadio mina una acícula y penetra en un brote joven actuando como El género Rhyacionia Hübner, [1825] barrenadora. -

Redalyc.Catalogue of Eucosmini from China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Zhang, A. H.; Li, H. H. Catalogue of Eucosmini from China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 33, núm. 131, septiembre, 2005, pp. 265-298 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45513105 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 265 Catalogue of Eucosmini from 9/9/77 12:40 Página 265 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 33 (131), 2005: 265-298 SRLPEF ISSN:0300-5267 Catalogue of Eucosmini from China1 (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) A. H. Zhang & H. H. Li Abstract A total of 231 valid species in 34 genera of Eucosmini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) are included in this catalo- gue. One new synonym, Zeiraphera hohuanshana Kawabe, 1986 syn. n. = Zeiraphera thymelopa (Meyrick, 1936) is established. 28 species are firstly recorded for China. KEY WORDS: Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Eucosmini, Catalogue, new synonym, China. Catálogo de los Eucosmini de China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Resumen Se incluyen en este Catálogo un total de 233 especies válidas en 34 géneros de Eucosmini (Lepidoptera: Tor- tricidae). Se establece una nueva sinonimia Zeiraphera hohuanshana Kawabe, 1986 syn. n. = Zeiraphera thymelopa (Meyrick, 1938). 28 especies se citan por primera vez para China. PALABRAS CLAVE: Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Eucosmini, catálogo, nueva sinonimia, China. Introduction Eucosmini is the second largest tribe of Olethreutinae in Tortricidae, with about 1000 named spe- cies in the world (HORAK, 1999). -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999 United States Renewable Rocky Department of Resources Mountain Agriculture Forest Health Region Management 2 FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION 1997-1999 by The Forest Health Management Staff Edited by Jeri Lyn Harris, Michelle Frank, and Susan Johnson December 2001 USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region Renewable Resources, Forest Health Management P.O. Box 25127 Lakewood, Colorado 80225-5127 Cover: Aerial photograph taken by Robert D. Averill on October 29, 1997, just days after a blowdown event occurred on the Routt National Forest. The picture was taken looking east toward a blowdown area that straddles both the Mt. Zirkel Wilderness and the Routt National Forest. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity employer.” Maps in this product are reproduced from geospatial information prepared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. GIS data and product accuracy may vary.