Summer Low Flow Events in the Mackenzie River System Ming-Ko Woo1,2 and Robin Thorne1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Tłı̨chǫ All-Season Road Executive Summary March 2016

Proposed Tłı̨chǫ All-season Road Executive Summary March 2016 Proposed Tłı̨ chǫ All-season Road Project Description Report March 2016 Department of Transportation i Proposed Tłı̨chǫ All-season Road Executive Summary March 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project description report (PDR) has been written to accompany the Type A Land Use Permit and Type B Water Licence applications to the Wekʼèezhìı Land and Water Board (WLWB) for development of the proposed T ł ı̨ c h ǫ All-season Road (TASR). These applications are being submitted by the Department of Transportation of the Government of the Northwest Territories (DOT – GNWT). The T ł ı̨ c h ǫ Government supports these applications. This project has been identified as a GNWT commitment under the Proposed Mandate of the Government of the Northwest Territories 2016-2019 (GNWT 2016). Over the years, DOT and T ł ı̨ c h ǫ Government have contemplated the possibility of improved transportation to the Wekʼèezhìı area. In 2011, both governments became reengaged under the T ł ı̨ c h ǫ Roads Steering Committee (TRSC) in order to assess the feasibility, desirability and implications of realigning the T ł ı̨ c h ǫ Winter Road System to provide improved community access. As of May 2013, the vision of the TRSC has been to pursue development of an all-season road. The route would end at the boundary of the community government of Whatì and predominantly follow ‘Old Airport Road,’ an existing overland alignment that was utilized up until the late 1980s as an overland winter road. The proposed TASR is defined as an all-season road approximately 94 km in length and 60 m in width with a cleared driving surface of approximately 8.5 m in width in order to accommodate a two lane gravel road with culverts and/or double lane bridges over water crossings as necessary. -

Mackenzie Highway Extension, for Structuring EIA Related Field Investigations and for Comparative Assessment of Alternate Routes

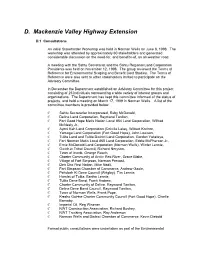

D. Mackenzie Valley Highway Extension D.1 Consultations An initial Stakeholder Workshop was held in Norman Wells on June 8, 1998. The workshop was attended by approximately 60 stakeholders and generated considerable discussion on the need-for, and benefits-of, an all-weather road. A meeting with the Sahtu Secretariat and the Sahtu Regional Land Corporation Presidents was held on November 12, 1998. The group reviewed the Terms of Reference for Environmental Scoping and Benefit Cost Studies. The Terms of Reference were also sent to other stakeholders invited to participate on the Advisory Committee. In December the Department established an Advisory Committee for this project consisting of 25 individuals representing a wide variety of interest groups and organizations. The Department has kept this committee informed of the status of projects, and held a meeting on March 17, 1999 in Norman Wells. A list of the committee members is provided below. C Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated, Ruby McDonald, C Deline Land Corporation, Raymond Taniton, C Fort Good Hope Metis Nation Local #54 Land Corporation, Wilfred McNeely Jr., C Ayoni Keh Land Corporation (Colville Lake), Wilbert Kochon, C Yamoga Land Corporation (Fort Good Hope), John Louison, C Tulita Land and Tulita District Land Corporation, Gordon Yakeleya, C Fort Norman Metis Local #60 Land Corporation, Eddie McPherson Jr., C Ernie McDonald Land Corporation (Norman Wells), Winter Lennie, C Gwich=in Tribal Council, Richard Nerysoo, C Town of Inuvik, George Roach, C Charter Community of Arctic Red -

Dease Liard Sustainable Resource Management Plan

Dease Liard Sustainable Resource Management Plan Background Document January, 2004 Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................. i List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... ii List of Maps ........................................................................................................................ ii List of Acronyms ...............................................................................................................iii Glossary .............................................................................................................................. v 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Plan Objectives ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background.............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 MSRM Mandate, Principals and Organizational Values......................................... 2 1.4 SRM Planning and Plans Defined............................................................................ 3 1.5 Scope of Dease-Liard SRM Plan ............................................................................. 5 1.6 The Process ............................................................................................................. -

Ancient Knowledge of Ancient Sites: Tracing Dene Identity from the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Christopher C

11 Ancient Knowledge of Ancient Sites: Tracing Dene Identity from the Late Pleistocene and Holocene Christopher C. Hanks The oral traditions of the Dene of the Mackenzie Valley contain some intriguing clues to cul tural identity associated with natural events that appear to have occurred at the end of the Pleisto cene and during the early Holocene. The Yamoria cycle describes beaver ponds that filled the ancient basins of postglacial lakes, while other narratives appear to describe the White River ash fall of 1250 B.P. This paper examines Dene views of the past and begins the task of relating them to the archaeological and geomorphological literature in an attempt to understand the cultural per spectives contained in these two different views of “history.” STORIES, NOT STONE TOOLS, UNITE US The Chipewyan, Sahtu Dene, Slavey, Hare, Mountain Dene, Dogrib, and Gwich’in are the Athapaskan-speaking people of the Northwest Territories. Collectively they refer to themselves as the Dene. Their shared cultural identity spans four distinct languages and four major dialects, and is spread from Hudson's Bay to the northern Yukon. Based on archaeological culture histories, there are relatively few strands of evidence that suggest a close relationship between these groups (Clark 1991; Hanks 1994). However, by using oral traditions, the archaeological record, linguistic theories, and the geological record, it can be argued that in the distant past the ancestors of the Dene lived as one group in the mountains along the Yukon-Alaskan border (Abel 1993: 9). For some archaeologists, the Athapaskan arrival east of the Cordilleran is implied by the appearance of a microlithic technology 6000-5000 B.P. -

August 8, 2013

August 8, 2013 The Sahtu Land Use Plan and supporting documents can be downloaded at: www.sahtulanduseplan.org Sahtu Land Use Planning Board PO Box 235 Fort Good Hope, NT X0E 0H0 Phone: 867-598-2055 Fax: 867-598-2545 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sahtulanduseplan.org i Cover Art: “The New Landscape” by Bern Will Brown From the Sahtu Land Use Planning Board April 29, 2013 The Sahtu Land Use Planning Board is pleased to present the final Sahtu Land Use Plan. This document represents the culmination of 15 years of land use planning with the purpose of protecting and promoting the existing and future well-being of the residents and communities of the Sahtu Settlement Area, having regard for the interests of all Canadians. From its beginnings in 1998, the Board’s early years focused on research, mapping, and public consultations to develop the goals and vision that are the foundation of the plan. From this a succession of 3 Draft Plans were written. Each Plan was submitted to a rigorous review process and refined through public meetings and written comments. This open and inclusive process was based on a balanced approach that considered how land use impacts the economic, cultural, social, and environmental values of the Sahtu Settlement Area. The current board would like to acknowledge the contributions of former board members and staff that helped us arrive at this significant milestone. Also, we would like to extend our gratitude to the numerous individuals and organizations who offered their time, energy, ideas, opinions, and suggestions that shaped the final Sahtu Land Use Plan. -

Movements and Distribution of the Bathurst and Ahiak Barren-Ground

Movements and distribution of the Bathurst and Ahiak barren-ground caribou herds 2005 Annual Report Submitted to West Kitikmeot Slave Study Society Submitted By Project Leader Anne Gunn Project Team Adrian D’Hont, Judy Williams Organisation Wildlife Division, Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife. 2 Summary: Objectives for 2005 included deploying 10 collars on cows from the Bathurst caribou herd and 10 collars on cows from the Ahiak caribou herd. A reconnaissance survey over the winter range of the Bathurst herd found heavy concentrations of caribou at Lac Grandin southeast to Rae Lakes and then low densities of caribou until east of Yellowknife. Of the 10 collars put on the Bathurst range, three died between April and June and the remaining seven calved on the Bathurst calving ground. Flights over the Ahiak winter range resulted in no caribou seen east of Contwoyto, low concentrations on the Back River and high concentrations east of Artillery Lake and in the Nonacho Lake area. Five collars were deployed east of Artillery Lake and five in the Nonacho Lake area. Of the five collars deployed in the Nonacho Lake area, two caribou migrated to the Bathurst calving ground. The remaining eight collars calved on the Ahiak calving ground. In 2005, in addition to addressing the objectives of the movement and distribution study for individual herds we successfully collared 12 cows from the Bathurst herd and 8 from the Ahiak herd. We also documented overlap in the winter distribution of Ahiak and Bathurst caribou at Nonacho Lake. Acknowledgements: West Kitikmeot Slave Study Society funded the study and we thank the Board for their continued support. -

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area's Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area’s Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community by Gwynneth Jones Research and & Aboriginal Law and Statistics Division Strategic Policy Group The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice Canada. i Table of Contents Abstract ii Author’s Biography iii I. Executive Summary iv II. Methodology/Introduction vi III. Narrative A. First Contact at Great Slave Lake, 1715 - 1800 1 B. Mixed-Ancestry Families in the Great Slave Lake Region to 1800 12 C. Fur Trade Post Life at 1800 19 D. Development of the Fur Trade and the First Mixed-Ancestry Generation, 1800 - 1820 25 E. Merger of the Fur Trade Companies and Changes in the Great Slave Lake Population, 1820 - 1830 37 F. Fur Trade Monopoly and the Arrival of the Missionaries, 1830 - 1890 62 G. Treaty, Traders and Gold, 1890 - 1900 88 H. Increased Presence and Regulations by Persons not of Indian/ Inuit/Mixed-Ancestry Descent, 1905 - 1950 102 IV. Discussion/Summary 119 V. Suggestions for Future Research 129 VI. References VII. Appendices Appendix A: Extracts of Selected Entries in Oblate Birth, Marriage and Death Registers Appendix B: Métis Scrip -- ArchiviaNet (Summaries of Genealogical Information on Métis Scrip Applications) VIII. Key Documents and Document Index (bound separately) Abstract With the Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Powley [2003] 2 S.C.R., Métis were recognized as having an Aboriginal right to hunt for food as recognized under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

PARTNERSHIPS 2019-2020 WATER STEWARDSHIP in the NORTHWEST TERRITORIES “I Had an Amazing Time at Little Doctor with My Family and Friends

NWT WATER STEWARDSHIP PARTNERSHIPS 2019-2020 WATER STEWARDSHIP IN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES “I had an amazing time at Little Doctor with my family and friends. It was an amazing experience that I hope to enjoy again soon.” Residents of the Northwest Territories (NWT) have a strong relationship with water. Clean and Kynidi Robillard, Age 13, Hay River 2018 Water Stewardship Youth Photo Contest Winner abundant water is essential to ecosystem health and the social, cultural and economic well-being of people living in the territory. Many people draw spiritual and cultural strength from the land and water. We drink water to stay healthy – both groundwater and surface water. We eat and use We depend on water for our economy, including plants, fish, and other animals that rely on water. of energy that can be used to generate electrical fur harvesting and fishing. Rivers are a source power. We use water to travel and transport goods during both the summer and winter. We all have a responsibility to care for the land and water. Our use of the water and land must not harm the water and aquatic ecosystems on which people, plants and animals depend. This responsibility is called water stewardship. The Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) supports and promotes the implementation of the Northern Voices, Northern Waters: NWT Water Stewardship Strategy (Water Strategy). The Water Strategy was released in 2010 with a vision that states: “The waters of the Northwest Territories will remain clean, abundant and productive for all time.” The GNWT is committed to working with water partners to achieve this vision. -

Table of Contents Waters of Opportunity

Table of Contents Waters of Opportunity .................... 1 Barrenlands and Great Respect and Responsibility ............ 2 Bear Lake .......................................11 Licence to Thrill .............................. 3 Mackenzie River and the Delta ...... 12 Epic Waters .................................... 4 Beaufort Sea and Arctic Ocean ..... 13 By Land, Water or Air ..................... 5 Our Specialties .............................. 14 Seasoned Operators ...................... 7 Getting Here .................................. 20 What to Bring ................................. 8 Map ............................................... 21 NWT Geographic ........................... 9 Operator Listings ........................... 23 14 Our Specialties BRUGGEN VAN JASON Great Slave Lake ............................10 Cover Photo Credit: Jason Van Bruggen The metric system is used for all measurements in this guide. Following are conversions of the more common uses: 1 kilometre (km) = .62 miles 1 metre (m) = 39 inches 1 kilogram (kg) = 2.2 pounds Indicates a member of Northwest Territories Tourism at the time of publication. The 2015 Sportfishing Guide is published by Northwest Territories DISCLAIMER – The information on services and licences Tourism, P.O. Box 610 Yellowknife NT X1A 2N5 Canada. contained in this book is intended for non-residents of the Toll free in North America 1-800-661-0788 Northwest Territories and non-resident aliens visiting Canada. Telephone (867) 873-5007 Fax (867) 873-4059 It is offered to you as a matter of interest and is believed Email: [email protected] Web: spectacularnwt.com to be correct and accurate at the time of printing. If you Production by Kellett Communications Inc., Yellowknife, would like to check the current licence status of a Northwest Northwest Territories. Printed in Canada for free distribution. Territories operator or to get an official copy of the NWT Fishing Regulations, please contact the Government of the Northwest Territories at (867) 873-7903. -

Northern Athapaskan Conference, V2

NATIONAL MUSEUM MUSÉE NATIONAL OF MAN DE L’HOMME MERCURY SERIES COLLECTION MERCURE CANADIAN ETHNOLOGY SERVICE LE SERVICE CANADIEN D’ETHNOLOGIE PAPER No.27 DOSSIER No. 27 PROCEEDINGS: NORTHERN ATHAPASKAN CONFERENCE, 1971 VOLUME TWO EDITED BY A.McFADYEN CLARK NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF CANADA MUSÉES NATIONAUX DU CANADA OTTAWA 1975 BOARD OF TRUSTEES MUSEES NATIONAUX DU CANADA NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF CANADA CONSEIL D'ADMINISTRATION Mr. George Ignatieff Chairman M. André Bachand Vice-Président Dr. W.E. Beckel Member M. Jean des Gagniers Membre Mr. William Dodge Member M. André Fortier Membre Mr. R.H. Kroft Member Mme Marie-Paule LaBrëque Membre Mr. J.R. Longstaffe Member Dr. B. Margaret Meagher Member Dr. William Schneider Member M. Léon Simard Membre Mme Marie Tellier Membre Dr. Sally Weaver Member SECRETARY GENERAL SECRETAIRE GENERAL Mr. Bernard Ostry DIRECTOR DIRECTEUR NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MAN MUSEE NATIONAL DE L ’HOMME Dr. William E. Taylor, Jr. CHIEF CHEF CANADIAN ETHNOLOGY SERVICE SERVICE CANADIEN D'ETHNOLOGIE Dr. Barrie Reynolds Crown Copyright Reserved Droits réservés au nom de la Couronne NATIONAL MUSEUM MUSÉE NATIONAL OF MAN DE L’HOMME MERCURY SERIES COLLECTION MERCURE ISSN 0316-1854 CANADIAN ETHNOLOGY SERVICE LE SERVICE CANADIEN D'ETHNOLOGIE PAPER NO.27 DOSSIER NO. 27 ISSN 0316-1862 PROCEEDINGS: NORTHERN ATHAPASKAN CONFERENCE, 1971 VOLUME TWO EDITED BY A. McFADYEN CLARK Cover Illustration: Contact traditional Kutchin camp based on a drawing from: "Journal du Yukon 1847-48" by Alexander Hunter Murray, Ottawa 1910, p. 86. NATIONAL MUSEUMS OF CANADA MUSÉES NATIONAUX DU CANADA OTTAWA 1975 OBJECT OF THE MERCURY SERIES The Mercury Series is a publication of the National Museum of Man, National Museums of Canada, designed to permit the rapid dissemination of information pertaining to those disciplines for which the National Museum of Man is responsible. -

Mackenzie River Basin Transboundary Waters Master Agreement

MACKENZIE RIVER BASIN TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS MASTER AGREEMENT BETWEEN: THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA as represented by the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (hereinafter referred to as "Canada") AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA as represented by the Minister of Environment, Lands and Parks (hereinafter referred to as "British Columbia") AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA as represented by the Minister of Environmental Protection (hereinafter referred to as "Alberta") AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF SASKATCHEWAN as represented by the Minister responsible for the Saskatchewan Water Corporation (hereinafter referred to as "Saskatchewan") AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES as represented by the Minister of Renewable Resources and the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories (hereinafter referred to as the "Northwest Territories") AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE YUKON as represented by the Minister of Renewable Resources (hereinafter referred to as the "Yukon") Hereinafter referred to collectively as "the Parties". WHEREAS the waters of the Mackenzie River Basin arise in or flow through British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon and are a precious resource; AND WHEREAS the waters of the Mackenzie River Basin should be managed to preserve the Ecological Integrity of the Aquatic Ecosystem; and to facilitate reasonable, equitable and sustainable use of this resource for present and future generations; AND WHEREAS -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. “Creating a Framework for the Wisdom of the Community”: Review of Victim Services in Nunavut, Northwest and Yukon Territories “Creating a Framework for the Wisdom of the Community:” Review of Victim Services in Nunavut, Northwest and Yukon Territories RR03VIC-3e Mary Beth Levan Kalemi Consultants Policy Centre for Research and Victim issues Statistics Division September 2003 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice Canada.