Possible Tool Use in a Mountain Gorilla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS February 10, 2010

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology NEWS February 10, 2010 Mountain Gorilla Census to Provide Current Status of Highly Endangered Species The current status of the critically endangered mountain gorilla will soon be revealed through a census to determine its population size in the Virunga Volcanoes area that straddles the borders of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Uganda in Eastern and Central Africa. The Virunga Volcanoes is one of only two locations where mountain gorillas live, whose total numbers are currently estimated at 680 individuals. Though the area is now relatively calm, recent conflict in the Mikeno sector of Virunga National Park in the DRC has left the gorillas there vulnerable. The last Virunga Volcanoes census in 2003 resulted in an estimate of 380 individuals, with the remaining individuals living in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park Uganda. The Wildlife and National Park Authorities of Uganda, Rwanda and the DRC will collaborate on the census, which is planned for March and April 2010. The census is an opportunity to make an accurate count of the total gorilla population in the Virunga Volcanoes. Fecal samples will also be collected for genetic analysis to confirm the population size and for better understanding the genetic variability and health status of the population. Such monitoring is vitally important in understanding the long-term viability and measuring the effects of recent history in the region on such a small population of critically endangered animals. Launching on March 1st, it will involve 80 team members. Team members, which will be drawn from the staff of the various protected area authorities and their partners, will traverse the entire Virunga gorilla habitat range over a period of approximately eight weeks. -

Energetic Responses to Variation in Food Availability in the Two Mountain Gorilla Populations (Gorilla Beringei Beringei)

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 158:487–500 (2015) Energetic Responses to Variation in Food Availability in the Two Mountain Gorilla Populations (Gorilla beringei beringei) Edward Wright,1* Cyril C. Grueter,2 Nicole Seiler,1 Didier Abavandimwe,3 Tara S. Stoinski,4 Sylvia Ortmann,5 and Martha M. Robbins1 1Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig 04103, Germany 2School of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology, The University of Western Australia,Crawley, Perth, WA 6009, Australia 3Karisoke Research Center, The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, Musanze, North Province, Rwanda 4The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, Atlanta, GA 30315, USA 5Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Berlin, Germany KEY WORDS food availability; energy intake rate; daily travel distance ABSTRACT Objective: Here, we compare food availability and relate this to differences in energy intake rates, time spent feeding, and daily travel distance of gorillas in the two populations. Comparative intraspecific studies investigating spatiotemporal variation in food availability can help us under- stand the complex relationships between ecology, behavior, and life history in primates and are relevant to under- standing hominin evolution. Differences in several variables have been documented between the two mountain gorilla populations in the Virunga Massif and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, but few direct comparisons that link ecological conditions to feeding behavior have been made. Materials and Methods: Using similar data collection protocols we conducted vegetation sampling and nutri- tional analysis on important foods to estimate food availability. Detailed observations of feeding behavior were used to compute energy intake rates and daily travel distance was estimated through GPS readings. Results: Food availability was overall lower and had greater temporal variability in Bwindi than in the Virungas. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Netzin G. Steklis “Nenetzin”, shortened to “Netzin”, is an Aztec name in the Nahuatl language (Nene=doll and ~tzin= of royalty, reverential) and is pronounced ‘net-scene’. Her name was given by her father, Dr. Rex E. Gerald, who was a MesoAmerican and Southwestern archaeologist. Maiden and publication names: C. Netzin Gerald, Netzin Gerald-Steklis, Netzin Gerald Steklis Personal information: Born 27 August 1967, in El Paso, TX ; Married with 2 children Contact information: [email protected] or [email protected] (520) 490-0595 Education 1971-78 Colegio Casa Montessori (K-5th, skipped 6th) Juarez, MEXICO 1978-80 Zach White & Lincoln Schools (7th-8th) El Paso, TX 1980-84 Coronado High School (9th-12th) El Paso, TX 1984-89 University of Chicago Chicago, IL B.A. in Anthropology (Biology concentration) 1995 Princeton University Princeton, NJ M.A. in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology Specialty Certification & Continued Education 1982-84 University of Texas El Paso, TX (computer programming and archaeology courses taken during high school) 1991 Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ Center for Remote Sensing & Spatial Analysis Environmental Resources (non-matriculating/audit courses) 1995 Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ Certificate, ArcView2 1996 Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc Philadelphia, PA ESRI Certificate, ARC/INFO 1996 Smithsonian Conservation Research Center Front Royal VA Conservation Applications of GIS 2005-06 University of Arizona Tucson, AZ Environmental Ethics Logic & Critical Thinking (non-matriculating/audit -

Download The

Habitat and Dietary Differences between Gorilla gorilla gorilla and Gorilla gorilla beringei: Implication for Social Variability by Jacklyn C. Bate B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 1985 B.A. Malaspina University College 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPLOGY And SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 2004 © Jacklyn C. Bate, 2004 Habitat and Dietary Differences between Gorilla gorilla gorilla and Gorilla gorilla beringei: Implication for Social Variability by Jacklyn C. Bate B.G.S., Simon Fraser University, 1985 B.A. Malaspina University College 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPLOGY And SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 2004 © Jacklyn C. Bate, 2004 Library Authorization In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Jacklyn C. Bate 15/04/04 Name of Author (please print) Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Title of Thesis: Habitat and Dietary Differences between Gorilla gorilla gorilla and Gorilla gorilla beringei: Implications for Social Variability Degree: M.A. -

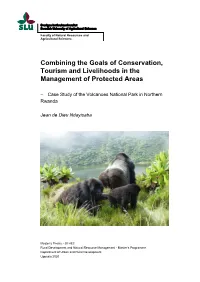

Combining the Goals of Conservation, Tourism and Livelihoods in the Management of Protected Areas

Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Combining the Goals of Conservation, Tourism and Livelihoods in the Management of Protected Areas – Case Study of the Volcanoes National Park in Northern Rwanda Jean de Dieu Ndayisaba Master’s Thesis • 30 HEC Rural Development and Natural Resource Management - Master’s Programme Department of Urban and Rural Development Uppsala 2020 Combining the Goals of Conservation, Tourism and Livelihoods in the Management of Protected Areas - Case Study of the Volcanoes National Park in Northern Rwanda. Jean de Dieu Ndayisaba Supervisor: Malin Beckman, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Urban and Rural Development. Examiner: Marien González Hidalgo, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Urban and Rural Development Assistant examiner: Harry Fischer, Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Department of Urban and Rural Development Credits: 30 HEC Level: Second cycle, A2E Course title: Master thesis in Rural Development Course code: EX0889 Course coordinating department: Department of Urban and Rural Development Programme/education: Rural Development and Natural Resource Management – Master’s Programme Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Picture showing the Mountain Gorillas in the Volcanoes National Park, as they were relaxing on the Bisoke Crater Lake inside the park. Some of them were standing and looking the scenery. Source: Jean Pierre Mucyo Samedi/DFGFI. Copyright: all featured images are used with permission -

Pattern of Cranial Ontogeny in Populations of Gorilla and Pan

PATTERN OF CRANIAL ONTOGENY IN POPULATIONS OF GORILLA AND PAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY JASON S. MASSEY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY KIERAN P. MCNULTY June 2018 © Jason S. Massey, 2018 Acknowledgments I am so deeply indebted to my advisor Dr. Kieran McNulty. I have known Kieran for many years, and in that time, he has provided me with every opportunity to succeed. My first field experience was at his site in Kenya, and since then he has guided me through stimulating areas of study, introduced me to colleagues that have expanded my research interests, and challenged me to be a better and focused researcher. I am an anthropologist because of him. Likewise, I could not have accomplished this without a strong and dedicated committee. I am so grateful for Drs. Martha Tappen, Michael Wilson, David Fox, and Anthony Weinhaus. The interesting discussions, challenging questions, access to data, and support over the many years have been integral to my success. I am also indebted to Drs. Bernard Wood and Shannon McFarlin. This dissertation would not exist without their dedicated support, funding, and patience. They have given me access to needed specimens and many summers of exciting fieldwork. I thank the Department of Anthropology and the community therein for so many years of emotional and academic support. In particular, I would like to thank Kara Kersteter, Nora Last, Megan Whaley, and Barbara London. Additionally, many summers of data collection and fieldwork were funded by numerous block grants and the Graduate Research Partnership Program. -

Unga Virunga Mountain Gorilla Project

VIRUNGAUNGA MOUNTAIN GORILLA Improving living conditions and habits in Rwanda through PROJECT efficient cooking stoves A LIKANO GmbH project in cooperation with IGCP and FAPDR CONTENTS 5— AT A GLANCE: VIRUNGA. MOUNTAIN. GORILLA. 7— IN BRIEF: GORILLAS. WOOD. PEOPLE. THE PROJECT: ENERGY. FIREWOOD. COOKING. 9— THE RAW MATERIAL WOOD 11— ENERGY & TECHNOLOGY 13— PRODUCTION 15— DELIVERY AND DISTRIBUTION 17— TESTIMONIALS THE CONTEXT: ECOSYSTEM. RAINFORESTS. BIODIVERSITY. 19— THE COUNTRY OF RWANDA 21— THE RWANDAN FORESTS 22 – 27— THE VOLCANOES & THEIR ECOSYSTEM 29— ALTERNATIVE ECONOMIES 31— THE MEETING WITH NATURE THE CONNECTION: LOCAL AND REGIONAL COOPERATION. 33— THE ROLE OF SUSTAINABILITY 35— THE NGOS: IGCP & FAPDR 37— THE OBJECTIVES OF THE UN AND THE CERTIFICATION LONG TERM: MOUNTAIN GORILLAS. RWANDA. FAMILIES. 39— MAKE A DIFFERENCE! 41— FURTHER READING Imprint Content by: LIKANO Project Development GmbH Wienerbergstrasse 11/12a, 1100 Vienna, Austria. Tel.: +43 1 934 67 49, [email protected], www.likano.eu Images, unless otherwise stated by LIKANO; page 4 (top left panel) and page 18: IGCP; page 20 (SDGs icons): www.un.org; page 25: copyright of Copernicus / processed by GeoVille on behalf of LIKANO. Illustrations, graphics and layout: Nathalie Aubourg (graphics.naau.at) Print production: Gradwohl Printproduktionen e.U. (www.mwgprint.at) 2nd extended edition. 300 copies. June 2017. 2 CONTENTS 3 VIRUNGA DR KONGO UGANDA MOUNTAINGORILLA Cyanika Rugamara Gahunga Kinigi Nyange Shingiro Volcanoes National Park Bugeshi Gataraga RWANDA Kabatwa Jenda Mukamira Bigogwe 0 5 10 km The VIRUNGA MOUNTAIN GORILLA PROJECT is a Gold Standard, micro-scale project been carried out in the bordering municipalities around the Volcanoes National Park The VIRUNGA MOUNTAIN GORILLA PROJECT UGANDA TANSANIA (Rwanda National Park). -

Rwanda 2021 Touring

RWANDA 2021 TOURING Kigali Tours 2 Volcanoes National Park Tours 5 Kigali City Tour 2 Dian Fossey Grave Trek 5 Agahazo Shalom Youth Village 2 Golden Monkey Trekking 5 Azizi Life Experience 3 Karisoke Research Center Visit 6 Dining Ideas in Kigali 3 Lake Kivu Tour 7 Musanze Tours 4 Imbabazi Center 7 Iby'Iwacu Cultural Village 4 Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project 4 Nyungwe Forest 8 Nyungwe Forest Canopy Walk 8 1 KIGALI TOURS Kigali City Tour A morning or an afternoon optional tour is available in Kigali. The city tour may include a visit to the Genocide Museum, a local market and artisan co-operatives like the Women for Women Organization (www.womenforwomen.org) and Indego Africa (https://indegoafrica.org/). Kigali has been the capital of Rwanda since 1965. An attractive city, it spreads over a number of hills and although it saw some difficult times through the genocide in 1994 and as power changed hands subsequently, it now has a pleasant, buoyant air. The main shopping and commercial area is centered around the Hotel Mille Collines, with the government district on the neighboring Kaciyiru hill. The markets, the handicrafts, the Muslim quarter and the genocide memorial in Gisozi are some of the main places of interest. Cost: Included in AAC’s Rwanda programs Agahazo Shalom Youth Village Rwanda has the highest proportion of orphans to the total population of under 18 year old children in the world. Agahzo Shalom is a residential and educational community and farm located outside of Kigali for orphaned children and vulnerable youth. It is home to 500 young people ages 14-21 from each of the 30 Rwandan districts. -

Reaching New Heights in 2019 Gorillas, Science, Sign Up! Free Monthly Community, and Gorilla Enews Education Gorillafund

THE Inside DIAN Our favorite events of the year 2 FOSSEY Young researchers becoming experts 5 Adopt a gorilla and help save a species 6 Gorılla Donor spotlight: Mikael Doktar 8 ournal November 2019 J Daily Protection | Scientific Research | Educating Conservationists | Helping Communities Reaching new heights in 2019 Gorillas, science, Sign up! Free monthly community, and Gorilla eNews education gorillafund. org/enews By Tara Stoinski, Ph.D. President and CEO/ Chief Scientific Officer I’m so pleased to report that this year — our 52nd since Dian Fossey founded the Karisoke Research Center — continued the upward trajectory we have seen in recent years. The mountain gorilla groups we protect had many infants, our teams in Congo continued to inspire us with We watched as little Uhirwe got her name in this year’s Kwita Izina Helping people. Saving gorillas. their protection of Grauer’s gorilla-naming ceremony, organized by the Rwandan government. The Gorilla Journal is a publicationgorillafund.org gorillas, and our people-centered programs mourning their dead or a long-term look at of the Dian Fossey in education and communities where we the shifting ranges of birds in gorilla habitat, Gorilla Fund® work continued to grow, innovate and make each one of these studies informs both our International, significant strides toward increasing sustain- basic knowledge and our ability to develop 800 Cherokee able conservation. effective conservation strategies (see story on Ave., SE, Atlanta, There were many highlights this year, two of our incredible young researchers on page 5). GA 30315-1440, 1-800-851-0203. some of which are detailed in this issue (see And, of course, we couldn’t be more pages 2–4 for a small sampling of our favorite about the progress being made on ©2019 Dian Fossey excited ® events of the year). -

Quadratic Relationships Between Group Size and Foraging Efficiency in a Herbivorous Primate

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Quadratic relationships between group size and foraging efciency in a herbivorous primate Received: 30 May 2018 Cyril C. Grueter 1,2,3,4, Andrew M. Robbins1, Didier Abavandimwe2, Veronica Vecellio2, Accepted: 18 October 2018 Felix Ndagijimana2, Tara S. Stoinski2,5 & Martha M. Robbins1 Published: xx xx xxxx The efect of feeding competition on foraging efciency is an important link between ecological factors and the social organization of gregarious species. We examined the efects of group size on daily travel distances, activity budgets, and energy intake of mountain gorillas in Rwanda. We measured daily travel distances of fve groups, activity budgets of 79 gorillas in nine groups, and energy intake data for 23 adult females in three groups over a 16-month period. Travel distances and the proportion of time spent traveling increased with size for most groups, which would be expected if their foraging efciency is limited by intragroup feeding competition. However, travel distances and times decreased for the largest group, which also had higher energy intake rates than intermediate sized groups. The improved foraging efciency of the largest group may be explained by advantages in intergroup contest competition. The largest group had much lower home range overlap than the other study groups which may be due to groups avoiding one another as a result of male mating competition. Collectively, our results indicate that intermediate sized groups had the lowest foraging efciency and provide a new twist on the growing evidence of non-linear relationships between group size and foraging efciency in primates. Feeding competition has been considered one of the most important links between ecological factors and the social organization of gregarious species1,2. -

Mountain Gorilla Exhibit Highlights Libraries’ Wildlife Conservation Manuscripts

Faculty rePortS MoUntaIn goRIlla exHIbIt HIgHlIgHts lIbRaRIes’ wIlDlIfe conseRvatIon ManUscRIPts Daniel reboussin dr. heather Campbell donated the Mist premiered in 171 countries and 45 the bob Campbell Papers to the languages on December 6, 2017. george A. Smathers libraries in Also on December 6th, Smathers 2015. Campbell’s best-known images Libraries with UF co-sponsors the brought international recognition to Dian Biodiversity Institute, Wildlife Ecology Fossey and her mountain gorilla research & Conservation, Department of at Rwanda’s Karisoke Research Center in Anthropology, Florida Museum of a January, 1970 National Geographic cover Natural History, Tropical Conservation story. To commemorate Karisoke’s 50th & Development program, Land Use and anniversary in September 2017, co-curators Environmental Change Institute, Center for Dan Reboussin and Richard Freeman, with African Studies, and International Center graduate student Riley Ravary, teamed up hosted Dr. Tara Stoinski, current President, to exhibit “Bob Campbell’s Photographs of CEO and Chief Scientific Officer for the Dian Fossey’s Karisoke Research Center, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, and David 1968-1972.” The exhibit is also available Watts, Professor of Anthropology at Yale online. University to present on conservation While bringing awareness to Campbell’s efforts at Karisoke since Fossey’s death in beautiful and historic photographs, the 1985. Watts was Karisoke Research Center exhibit also highlights one of the largest director 1986-1987. collections of primary resources on 20th These preeminent primatologists’ century African wildlife conservation in perspectives on mountain gorilla the US. These primary resources include conservation since the early days of gifts from Brian Child (Geography), a Sunbird from the audio, explaining “I Fossey’s research highlighted innovative Larry D. -

Evaluation of Craniofacial Superimposition As a Technique for Measuring Mountain Gorilla Facial Soft Tissue Depth and Implications for Hominid Facial Approximation

Evaluation of Craniofacial Superimposition as a Technique for Measuring Mountain Gorilla Facial Soft Tissue Depth and Implications for Hominid Facial Approximation by Marli Richmond B.A. in Anthropology, May 2015, East Carolina University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 20, 2018 Thesis directed by Shannon McFarlin Associate Professor of Anthropology Acknowledgments I express my sincerest appreciation for my advisor, Shannon McFarlin, for her guidance, patience, and encouragement of my research and development as a graduate student and anthropologist. My gratitude goes to the Mountain Gorilla Skeletal project, for curating the research sample used in this study, and Jason Massey for his tremendous effort in making the skeletal material used in this research available for study. The MGSP collection is supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (BCS-0852866, BCS- 0964944, BCS-1520221), National Geographic Society’s Committee for Research and Exploration (8486-08), and The Leakey Foundation as well as the Rwanda Development Board’s Department of Tourism and Conservation, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, Gorilla Doctors, The George Washington University, New York University College of Dentistry, Institute of National Museums of Rwanda, and other universities in Rwanda and the U.S.A. I am extremely grateful to Jordi Galbany for his time and work collecting gorilla tissue thickness measurements in the field, and to the Gorilla Doctors for making these data available. I am indebted to the staff of Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International’s Karisoke Research center, who work tirelessly toward the observation and protection of mountain gorillas, and the preservation of their skeletal remains.