The Narrative Persona of Martin Amis: a Transitional Stylistic Bridge Between Postmodernism and New Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesis and Development of Stylistic Devices Classifications

Philology Matters Volume 2020 Issue 3 Article 6 9-20-2020 GENESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF STYLISTIC DEVICES CLASSIFICATIONS Feruza Khajieva Associate professor (PhD), Department of English Literature Bukhara State University, Bukhara, Uzbekistan Follow this and additional works at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/philolm Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, Linguistics Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Khajieva, Feruza Associate professor (PhD), Department of English Literature (2020) "GENESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF STYLISTIC DEVICES CLASSIFICATIONS," Philology Matters: Vol. 2020 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. DOI: 10. 36078/987654447 Available at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/philolm/vol2020/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philology Matters by an authorized editor of 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Khajieva: GENESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF STYLISTIC DEVICES CLASSIFICATIONS Philology Matters / ISSN: 1994-4233 2020 Vol. 33 No. 3 LINGUISTICS ФМ Uzbek State World Languages University DOI: 10. 36078/987654447 Feruza Khajieva Феруза Ҳожиева Associate professor (PhD), Department of English Бухоро давлат университети, Инглиз адабиёти Literature, Bukhara State University кафедраси доценти, филология фанлари бўйича фалсафа доктори GENESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF STYLISTIC DEVICES СТИЛИСТИК ВОСИТАЛАР ТАСНИФ- CLASSIFICATIONS ЛАРИ ГЕНЕЗИСИ ВА ТАДРИЖИ ANNOTATION АННОТАЦИЯ Тhe article discusses the problem of a stylistic Мақолада стилистик воситалар муаммо- device, its innate features and the literary, си, жумладан, уларнинг табиати ҳамда ва ба- aesthetic, imagery functions, the example to диий-эстетик, образлилик вазифалари таҳлил stylistic convergence is also given. -

The Limits of Irony: the Chronillogical World Of

THELIMITS OF IRONY The Chronillogical World of Martin Arnis' Time's Arrow s a work of Holocaust fiction, Martin Arnis' Time'sArrm is as A, oving and disturbing as it is ingenious; indeed, it is Amis' narrative ingenuity that is responsible for the work's moral and emotional impact. What moves and disturbs the reader is the multitude of ironies that result from the reversal of time- the "narrative conceitn (Diedrick 164) that structures and drives the novel.' In Time'sArrow the normal present-to-future progression becomes the movement from present to past and the normative convention of realistic fiction-the inability to foresee the future- becomes the inability to recall the past. A narrator in Amis' Einstein's Monsters describes the 20th-century as "the age when irony really came into its own" (37) and Time'sAwow is an ironic tour-de-force if ever there was one. The minor and major ironies generated by the time- reversal all follow from the most important effect of the trope- the reversal of all normal cause-effect relations. (The minor become major as the reverse becomes increasinglypmerse.) The irony is structural-formal when the reader recognizes that the novel is an inverted Bihhngsromn- detailing the devolution of the protagonist- and an autobiography told by an amnesiac; but as might be expected, the trope results in an array of more locally comic, and then, grimly dark ironies. Indeed, the work's most disturbing effects are the epistemological and, ultimately, onto- logical uncertainties which are the cumulative impact of the narrative method. -

Cover Boys Books Entertainment Smh.Com.Au

Cover boys Books Entertainment smh.com.au http://www.smh.com.au/news/books/coverboys/2005/12/29/113573267... Cover boys Stephen King and Martin Amis. Photo: John Shakespeare December 29, 2005 Never write sex scenes. A weird story is best kept a short story. Martin Amis and Stephen King slug it out onstage. Madeleine Murray takes notes. No writers could be more different than Martin Amis and Stephen King. Amis, enfant terrible of the British literati, inherited his famous father's flair for lacerating, bilious prose. King never knew his father, who left his Maine home to get cigarettes one evening in 1949 and disappeared forever. His mother supported her two young sons by working in a home for the mentally ill. Amis's first novel concerned an Oxfordbound adolescent determined to sleep with an older woman. King's first published story, I was a Teenage Grave Robber, about a scientist who bred giant maggots, appeared in Comics Review in 1967. Amis has been shortlisted for the Booker prize, but only a couple of his novels have ever been filmed, quite forgettably. Intellectuals poohpooh King, yet more than 90 of his stories have been adapted for TV and films. Yet on this Saturday morning at The New Yorker festival, the prince and the showman were meeting three other writers to discuss fantasy and invention in fiction. King, rangy and relaxed, seemed to have recovered from his gruesome accident on a deserted Maine road six years ago. While trying to stop one of his Rottweilers rummaging in a beer cooler, Bryan 1 of 5 11/25/2006 11:26 AM Cover boys Books Entertainment smh.com.au http://www.smh.com.au/news/books/coverboys/2005/12/29/113573267.. -

Post Nuclear Apocalyptic Vision in Martin Amis's Einstein's Monsters

Post Nuclear Apocalyptic Vision in Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters The research paper aims to analyze the study of Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters in order to exhibit the philosophical concept of dystopia or anti-utopia. With the abundant evidences from stories and an essay which are collected in Einstein’s Monsters, the researcher comes to find out that utopia cannot be maintained by Europeans due to several reasons, for instance, proliferation of nuclear nukes, unchecked flourishments of industrialization, sense of egotism, escalation of science and technology and many more. In doing so, the researcher has brought the concept of Krishan Kumar and M. Keith Booker. The theoretical concept of ‘anti-utopia’ is proposed by Krishan Kumar’s Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times. Simultaneously, concept of ‘cacotopia’ is proposed by M. Keith Booker in The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature which does not celebrate the end of the world rather it warns the mankind for their massive destructive activities which create artificial apocalypse. These philosophical concepts can be applied and vividly found in Martin Amis’s Einstein’s Monsters. Basically, this research paper focuses on the five stories namely “Bujak and the Strong Force,” “Insight at Flame Lake,” “The Time Disease,” “The Little Puppy That Could” and “The Immortals” where these stories portray the post nuclear apocalyptic vision which, obviously, demonstrates the philosophical concept of dystopia. It further explores the Bernard Brodie’s concept of nuclear deterrence which discourages in the launching of nuclear wars. The research paper also illustrates the ruin of European world of utopia by showing the destruction created by nuclear nukes. -

Lexical Stylistic Devices and Literary Terms of Figurative Language

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8, Issue-3S, October 2019 Lexical Stylistic Devices and Literary Terms of Figurative Language Saidova Mukhayyo Umedilloevna Abstract: The degree of study and significance of lexical II. MATERIALS AND METHODS literary devices are carried out in the given article. The essential aspects of lexical devices and information about numerous The scientific and practical studies about linguistic terms methods of investigating and studying them are discussed. are based on ideas of Akhmanova (1966, 1990), Vasileva Terms belonged to the lexical level of the language and the (1998), Gwishiani (1986, 1990), Golovin (1976), Kulikova analyses of lexical devices given by several dictionaries of (2002), Petrosyants (2004), Podolskaya (1988), Slyusarova literary terms and sources are explained in the article. In this (1983, 2000), Shelov (1998) and others. In recent years, article we would like to refer to different approaches on study of studies on linguistic terms have been published and we can literary terms of figurative language, more preciously on lexical see these studies on Roman language terminology in works of stylistic devices. There are many types of figurative language, including literary devices such Nikulina (1990), Utkina (2001), Emelyanova (2000), as simile, metaphor, personification and many others. The Vermeer (1971), Zakharenkova (1999), German (1990), definition of figurative language is opposite to that of literal Golovkina (1996) [6, 11-41]. language, which involves only the “proper” or dictionary If we pay close attention to the aforesaid studies, we can definitions of words. Figurative language usually requires the see that literary terms which is the object of our research reader or listener to understand some extra nuances, context and project has been studied relatively rarely in Slovenian, allusions in order to understand the second meaning. -

DOI: 10.1515/Genst-2017-0012 CLASS and GENDER

DOI: 10.1515/genst-2017-0012 CLASS AND GENDER – THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN KINGSLEY AMIS’S LUCKY JIM MILICA RAĐENOVIĆ “Dr Lazar Vrkatić” Faculty of Law and Business Studies 76, Oslobodenjia Blvd 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia [email protected] Abstract: Lucky Jim is one of the novels that mark the beginning of a small subgenre of contemporary fiction called the campus novel. It was written and published in the 1950s, a period when more women and working-class people started attending universities. This paper analyses the representation of women in terms of their gender and class. Keywords: campus novel, class, gender. 1. Introduction After six years of war, Great Britain was hungry for change and craved a more egalitarian society. After the Labour Party came to power in July 1945 with a huge parliamentary majority, the new government started paving the way for a Welfare State, which involved the expansion of the system of social security, providing pensions, sickness and unemployment benefits, a free National Health Service, the funding and expansion of the 183 secondary school system, and giving poor children greater opportunity to attend universities. The Conservative Party returned to power in 1951 but did not make any changes to the measures that brought about the creation of the Welfare State (Davies 2000:51). Once a great world power turned to reshaping its society, in which the class system would become a thing of the past, its people believed that they were living in a country that was going through great changes (Brannigan 2002:3). The Education Act of 1944 was intended to open universities to everyone and thus expand the trend of educational opportunities to the less privileged in the society. -

Political Discourse in Martin Amis's Other People: a Mystery Story

Martin, Karl, and Maggie Too: Political Discourse in Martin Amis’s Other People: A Mystery Story Stephen Jones common thread that runs throughout criticism of Martin Amis’s Awork is a concentration on the formal aspects of his writing. In his earlier work, this concentration often comes at the expense of his novels’ political content. Martin Cropper has written that: Martin Amis has published two novels worth re-reading, his third and fourth: Success (1978) and Other People: A Mystery Story (1981). Each is structurally exquisite—a double helix; a Möbius strip (Cropper, p.6) While I would argue that all of Amis’s work is worth reading regardless, and possibly because, of any ‘aesthetic shortcomings’ that Cropper may identify, his description of Amis’s precise structuring is enlightening. The analogy to the mathematical structures of a double helix and a Möbius strip suggests the precision and rigidity with which Amis has ‘calculated’ his narrative structures, and it is the Möbius strip structure of Other People: A Mystery Story (1981) in particular that appears to have distracted many critics from any political content that the novel may contain. Brian Finney pays close attention to the novel’s metafictional elements, concluding that its cyclical structure entraps ‘the narrator and the reader ... in the web of the fictional construct’ (Finney, p.53). Finney’s suggestion is that the main purpose of the novel’s metafictional devices is to draw attention to the problems of narrative closure. While Finney is correct in noting this, it is also possible to read these devices as drawing attention to social as well as narrative issues. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 447 Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Philosophy of Education, Law and Science in the Era of Globalization (PELSEG 2020) Stylistic Devices of Creating a Portrait of the Character Artistic Image (Based on the Work of Thomas Mayne Reid) V. Vishnevetskaya 1Novorossiysk Polytechnic Institute (branch) of Kuban State Technological University 20, ul. Karl Marx, Novorossiysk, 353900, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract —The article considers the stylistic devices used for II. MATERIALS AND METHODS the portrait description of the character of the artwork. It is necessary to emphasize that stylistic devices play quite an In our work, we use the methods of comparing and important role in creating the artistic image of the character. At contrasting which help the author to create special portrait of a the same time, stylistic devices mainly emphasize not only the character. Stylistic devices are important line elements of the specific features of the exterior, but also various aspects of the portrait description. The process of creating a character visual impression, while bringing to the forefront the features of portrait image uses all the existing stylistic devices that are the drawing image that seem important to the author for one used in the English language system. The most used stylistic reason or another. And, here, the emotional characteristic of the devices are metaphor, epithet, comparison, metonymy and portrait described is becoming significant, and the impression others. that the image formed by the author can make. Stylistic devices are an important line element of the portrait description. -

Translation of Stylistic Devices in Contemporary Young Adult Fiction

ISSN 1648-8776 JAUNŲJŲ MOKSLININKŲ DARBAI. Nr. 2 (46). 2016 Doi: 10.21277/jmd.v2i46.60 TRANSLATION OF STYLISTIC DEVICES IN CONTEMPORARY YOUNG ADULT FICTION Roberta Strikauskaitė Šiauliai University Introduction Translation of fiction Due to the increasing teenage interest in Translation as such first and foremost is an books, scripture becomes a source of language, in activity for social purposes the aim of which is a sense that youngsters learn new words, phrases, communication. As a process it consists of a number of allusions or metaphors and incorporate them in their stages, each of them being equally important in order everyday language. K. Urba (2013) describes the to convey the idea of the source text in the highest situation of teen literature in Lithuania as relatively quality. Navickienė (2005, p. 30) has determined four bad compared to that in other countries. Therefore, steps and defined them as: 1) analysis of the original demand for popular reads requires a quick reaction text; 2) search for equivalents; 3) synthesis of the when translating such books. However, translating original features and equivalents; 4) analysis of the young adult fiction is a challenging task due to the use translated text. of slang and other colloquial vocabulary or stylistic Analysis of the original helps to determine the devices. type of the text and thus distinguishes the purpose of The stylistic side of translation (and writing translation. Search for equivalents results in choosing to some extent) plays one of the biggest roles in a translation technique, scanning for culture-specific providing readership with a proper equivalent of terms and their counterparts relevant to the speakers fiction. -

Nabokovilia: References to Vladimir Nabokov in British and American Literature and Culture, 1960-2009

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2011 Nabokovilia: References to Vladimir Nabokov in British and American Literature and Culture, 1960-2009 Juan Martinez University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, American Material Culture Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Martinez, Juan, "Nabokovilia: References to Vladimir Nabokov in British and American Literature and Culture, 1960-2009" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1459. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/3476293 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NABOKOVILIA: REFERENCES TO VLADIMIR NABOKOV IN BRITISH AND AMERICAN LITERATURE AND CULTURE, 1960-2009 by Juan Martinez Bachelor of -

Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond, Edited by Gavin Keulks 102 Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond a Lethal Hostility to Deviation Or Resistance

7 Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow and the Postmodern Sublime Brian Finney California State University, Long Beach Time’s Arrow (1991) confronts a question that has consumed Amis from an early stage in his career: is modernity leading civilization to self-destruction? While his main concern remains the world’s develop- ment of nuclear weapons, he sees the origins of the West’s drive to implode not just in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but in the Holocaust (Time’s Arrow) and the Soviet gulags (Koba the Dread). The Holocaust is, he has said, “the central event of the twentieth century” (Bellante, 16). As Dermot McCarthy observes: Amis’s “generation suffers from an event it did not experience, and will expire from one it seems power- less to prevent” (301). James Diedrick has called Einstein’s Monsters (1987), London Fields (1989), and Time’s Arrow an “informal trilogy” (104). The first two focus on a nuclear holocaust that threatens postwar civilization, whereas Time’s Arrow returns to the Holocaust, which cast its shadow over the rest of the century. London Fields and Time’s Arrow complement one another in particular. In a prefatory note to London Fields Amis mentions that he even considered calling the novel by the latter’s title. Indeed, Hitler remains at the heart of Amis’s belief that we are living in the aftermath of disaster. In London Fields Nicola Six remarks that “it seemed possible to argue that Hitler was still running the century” (395), and in 2002 Amis confessed, “I feel I have unfinished business with Hitler” (Heawood, 18). -

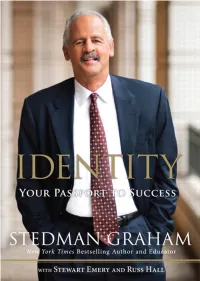

Identity: Your Passport to Success

Praise for Identity: Your Passport to Success “I wish someone like him [Stedman Graham] had been around to enlighten me at an age when finding myself and a career change or decision was within easy reach…all I needed, as he formulated, was a ‘process.’” —Janice Jones, Junior Achievement of Chicago “Stedman Graham learned years ago that the secret to a successful life was to not let other people define him, but rather to define himself. As his thought-provoking book shows, finding your true identity is not as easy as it seems. Filled with inspiring real-life stories and life- changing insights, this page-turner of a book will snap you out of your complacency and make you think: Who are you, deep-down? What do you value, seriously? And what do you really want to do with your life? Don’t miss this outstanding book.” —Ken Blanchard, coauthor of The One Minute Manager® and Leading at a Higher Level “Get clear on who you are and live according to your own definition of success. Stedman Graham’s Identity offers thought-provoking questions, strategies, and stories to expedite your journey to success. This is a must-read!” —Stuart Johnson, Founder & CEO, VideoPlus and SUCCESS Partners “Stedman Graham is a man who stands tall and speaks from the heart. His insights and advice have provided a road map for success, which I have found invaluable.” —Chas Edelstein, Co-CEO, Apollo Group, Inc. (owner of University of Phoenix) “Identity is an inspirational, honest, and clearly written book about how you can understand and make choices in your life where you matter and fit in a world full of personal challenges.