The Limits of Irony: the Chronillogical World Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Fiction Today

Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. This is an author-produced version of a paper published in British Fiction Today (ISBN 0826487319). This version has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof corrections, published layout or pagination. All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Citation for this version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. London: Birkbeck ePrints. Available at: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/archive/00000437 Citation for the publisher’s version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Contact Birkbeck ePrints at [email protected] The Middle Years of Martin Amis Joseph Brooker Martin Amis (b.1949) was a fancied newcomer in the 1970s and a defining voice in the 1980s. He entered the 1990s as a leading player in British fiction; by his early forties, the young talent had grown into a dominant force. Following his debut The Rachel Papers (1973), he subsidised his fictional output through the 1970s with journalistic work, notably as literary editor at the New Statesman. -

Martin Amis Is Tired. Near the End of a 30 City Tour Promoting His New Book, the Memoir Experience, Amis Exudes and Embodies Exhaustion

Interview | Martin Amis http://www.janmag.com/profiles/amis.html Top Agents Seek Authors Master's in Writing Free list of the top agents to help you get Johns Hopkins University MD & DC School published. Get it now. of Arts & Sciences Nights Martin Amis is tired. Near the end of a 30 city tour promoting his new book, the memoir Experience, Amis exudes and embodies exhaustion. A diminutive man with an appearance that is somehow surprisingly frail in a writer of this stature (as though a writer should somehow be as large as his reputation. Were that the case, Amis would be as big and imposing as a country manor). In fact, his appearance is surprising in all ways. There is more to his mien of aging rock musician than worldclass author. 1 of 13 10/3/2006 10:00 AM Interview | Martin Amis http://www.janmag.com/profiles/amis.html The rock star analogy may have been enhanced by the challenges of not only getting this interview, but of getting to keep it. To arrange the interview, numerous telephone calls and emails to the literary capitals in several countries were necessary. To keep it, the January crew arrived for our 4:45 interview to be met with the smallest view of bedlam. The television interview that preceded us had gone way over time, resulting in a phalanx of journalists and photographers lining the hotel corridor outside the special smoking suite where Amis was trapped with the TV people. The TV cameras were still being packed up when Amis was ushered down the hall to a photo shoot and then back to the suite to talk with me. -

Construing the Elaborate Discourse of Thomas More's Utopia

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2006 Irony, rhetoric, and the portrayal of "no place": Construing the elaborate discourse of Thomas More's Utopia Davina Sun Padgett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Davina Sun, "Irony, rhetoric, and the portrayal of "no place": Construing the elaborate discourse of Thomas More's Utopia" (2006). Theses Digitization Project. 2879. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2879 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONY, RHETORIC, AND THE PORTRAYAL OF "NO PLACE" CONSTRUING THE ELABORATE DISCOURSE OF THOMAS MORE'S UTOPIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Davina Sun Padgett June 2006 IRONY,'RHETORIC, AND THE PORTRAYAL OF "NO PLACE": CONSTRUING THE ELABORATE DISCOURSE OF THOMAS MORE'S UTOPIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Davina Sun Padgett June 2006 Approved by: Copyright 2006 Davina Sun Padgett ABSTRACT Since its publication in 1516, Thomas More's Utopia has provoked considerable discussion and debate. Readers have long grappled with the implications of this text in order to determine the extent to which More's imaginary island-nation is intended to be seen as a description of the ideal commonwealth. -

Political Discourse in Martin Amis's Other People: a Mystery Story

Martin, Karl, and Maggie Too: Political Discourse in Martin Amis’s Other People: A Mystery Story Stephen Jones common thread that runs throughout criticism of Martin Amis’s Awork is a concentration on the formal aspects of his writing. In his earlier work, this concentration often comes at the expense of his novels’ political content. Martin Cropper has written that: Martin Amis has published two novels worth re-reading, his third and fourth: Success (1978) and Other People: A Mystery Story (1981). Each is structurally exquisite—a double helix; a Möbius strip (Cropper, p.6) While I would argue that all of Amis’s work is worth reading regardless, and possibly because, of any ‘aesthetic shortcomings’ that Cropper may identify, his description of Amis’s precise structuring is enlightening. The analogy to the mathematical structures of a double helix and a Möbius strip suggests the precision and rigidity with which Amis has ‘calculated’ his narrative structures, and it is the Möbius strip structure of Other People: A Mystery Story (1981) in particular that appears to have distracted many critics from any political content that the novel may contain. Brian Finney pays close attention to the novel’s metafictional elements, concluding that its cyclical structure entraps ‘the narrator and the reader ... in the web of the fictional construct’ (Finney, p.53). Finney’s suggestion is that the main purpose of the novel’s metafictional devices is to draw attention to the problems of narrative closure. While Finney is correct in noting this, it is also possible to read these devices as drawing attention to social as well as narrative issues. -

The Concept of Irony in Ian Mcewan's Selected Literary Works

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bc. Eva Mádrová Concept of Irony in Ian McEwan’s Selected Literary Works Diplomová práce PhDr. Libor Práger, Ph.D. Olomouc 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci na téma “Concept of Irony in Ian McEwan’s Selected Literary Works” vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne Podpis I would like to thank my supervisor PhDr. Libor Práger, Ph.D. for his assistance during the elaboration of my diploma thesis, especially for his valuable advice and willingness. Table of contents Introduction 6 1. Ian McEwan 7 2. Methodology: Analysing irony 8 2.1 Interpreter, ironist and text 8 2.2 Context and textual markers 10 2.3 Function of irony 11 2.4 Postmodern perspective 12 3. Fiction analyses 13 3.1 Atonement 13 3.1.1 Family reunion ending as a trial of trust 13 3.1.2 The complexity of the narrative: unreliable narrator and metanarrative 14 3.1.3 Growing up towards irony 17 3.1.4 Dramatic encounters and situations in a different light 25 3.2 The Child in Time 27 3.2.1 Loss of a child and life afterwards 27 3.2.2 The world through Stephen Lewis’s eyes 27 3.2.3 Man versus Universe 28 3.2.4 Contemplation of tragedy and tragicomedy 37 3.3 The Innocent 38 3.3.1 The unexpected adventures of the innocent 38 3.3.2 The single point of view 38 3.3.3 The versions of innocence and virginity 40 3.3.4 Innocence in question 48 3.4 Amsterdam 50 3.4.1 The suicidal contract 50 3.4.2 The multitude -

Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond, Edited by Gavin Keulks 102 Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond a Lethal Hostility to Deviation Or Resistance

7 Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow and the Postmodern Sublime Brian Finney California State University, Long Beach Time’s Arrow (1991) confronts a question that has consumed Amis from an early stage in his career: is modernity leading civilization to self-destruction? While his main concern remains the world’s develop- ment of nuclear weapons, he sees the origins of the West’s drive to implode not just in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but in the Holocaust (Time’s Arrow) and the Soviet gulags (Koba the Dread). The Holocaust is, he has said, “the central event of the twentieth century” (Bellante, 16). As Dermot McCarthy observes: Amis’s “generation suffers from an event it did not experience, and will expire from one it seems power- less to prevent” (301). James Diedrick has called Einstein’s Monsters (1987), London Fields (1989), and Time’s Arrow an “informal trilogy” (104). The first two focus on a nuclear holocaust that threatens postwar civilization, whereas Time’s Arrow returns to the Holocaust, which cast its shadow over the rest of the century. London Fields and Time’s Arrow complement one another in particular. In a prefatory note to London Fields Amis mentions that he even considered calling the novel by the latter’s title. Indeed, Hitler remains at the heart of Amis’s belief that we are living in the aftermath of disaster. In London Fields Nicola Six remarks that “it seemed possible to argue that Hitler was still running the century” (395), and in 2002 Amis confessed, “I feel I have unfinished business with Hitler” (Heawood, 18). -

Narrative and Narrated Homicide" : the Vision of Contemporary Civilisation in Martin Amis's Postmodern Detective Fiction

Title: "Narrative and narrated homicide" : the vision of contemporary civilisation in Martin Amis's postmodern detective fiction Author: Joanna Stolarek Citation style: Stolarek Joanna. (2011). "Narrative and narrated homicide" : the vision of contemporary civilisation in Martin Amis's postmodern detective fiction. Praca doktorska. Katowice : Uniwersytet Śląski University of Silesia English Philology Department Institute of English Cultures and Literatures Joanna Stolarek „Narrative and Narrated Homicide”: The Vision of Contemporary Civilisation in Martin Amis’s Postmodern Crime Fiction Supervisor : Prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Białas Katowice 2011 1 Uniwersytet Śląski Wydział Filologiczny Instytut Kultury i Literatury Brytyjskiej i Ameryka ńskiej Joanna Stolarek „Narratorska i narracyjna zbrodnia: Wizja współczesnej cywilizacji w postmodernistycznych powie ściach detektywistycznych Martina Amisa Promotor : Prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Białas Katowice 2011 2 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: Various trends and tendencies in 20 th century detective fiction criticism ............................................................................. 24 1.1. Crime fiction as genre and as popular literature ........................................ 24 1.2. A structural approach to detective fiction .................................................. 27 1.3. Traditional and modern aspects of crime literature in hard-boiled detective fiction ........................................................................................... -

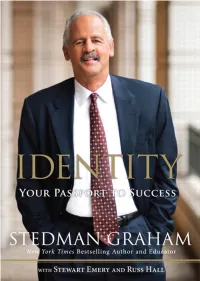

Identity: Your Passport to Success

Praise for Identity: Your Passport to Success “I wish someone like him [Stedman Graham] had been around to enlighten me at an age when finding myself and a career change or decision was within easy reach…all I needed, as he formulated, was a ‘process.’” —Janice Jones, Junior Achievement of Chicago “Stedman Graham learned years ago that the secret to a successful life was to not let other people define him, but rather to define himself. As his thought-provoking book shows, finding your true identity is not as easy as it seems. Filled with inspiring real-life stories and life- changing insights, this page-turner of a book will snap you out of your complacency and make you think: Who are you, deep-down? What do you value, seriously? And what do you really want to do with your life? Don’t miss this outstanding book.” —Ken Blanchard, coauthor of The One Minute Manager® and Leading at a Higher Level “Get clear on who you are and live according to your own definition of success. Stedman Graham’s Identity offers thought-provoking questions, strategies, and stories to expedite your journey to success. This is a must-read!” —Stuart Johnson, Founder & CEO, VideoPlus and SUCCESS Partners “Stedman Graham is a man who stands tall and speaks from the heart. His insights and advice have provided a road map for success, which I have found invaluable.” —Chas Edelstein, Co-CEO, Apollo Group, Inc. (owner of University of Phoenix) “Identity is an inspirational, honest, and clearly written book about how you can understand and make choices in your life where you matter and fit in a world full of personal challenges. -

Gristwold on Platonic Irony

84 Philosophy and Literature Charles L. Griswold, Jr. IRONY IN THE PLATONIC DIALOGUES I nterpreters of Plato have arrived at a general consensus to the Ieffect that there exists a problem of interpretation when we read Plato, and that the solution to the problem must in some way incorporate what has tendentiously been called the “literary” and the “philosophi- cal” sides of Plato’s writing. The problem is created by the fact that Plato wrote in dialogue form, indeed a specific type of dialogue form. The solution must somehow combine into a coherent theory of the “meaning” of the dialogues, the ways in which these texts work (such as the use of imagery, metaphor, myth, allusion, irony, as well as argu- ment). At the same time, there exists enormous disagreement about how one ought to move from these general observations to interpreta- tion of a particular text.1 The problem of interpretation lies not merely in the fact that Plato wrote dialogues. That alone would not necessarily present any herme- neutical issues of unusual difficulty. Plato’s distinctive use of the dialogue form creates the difficulties. The genre that we might call “the Platonic dialogue” is distinguished by several relevant characteristics. First, there is no character called “Plato” who speaks in any of the dialogues; indeed, “Plato” is mentioned twice in the entire corpus, once as being absent (Pho. 59b10), and once as being present (Apol. 38b6). Authorial anonymity is thus an important feature of the dialogues.2 At least ab initio, we are not justified in identifying Plato with any one of his characters. -

Comic Vision and Comic Elements of the 18 Century Novel Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Sayı 25/1,2016, Sayfa 230-238 COMIC VISION AND COMIC ELEMENTS OF THE 18TH CENTURY NOVEL MOLL FLANDERS BY DANIEL DEFOE Gülten SİLİNDİR∗ Abstract “It is hard to think about the art of fiction without thinking about the art of comedy, for the two have always gone together, hand in hand” says Malcolm Bradbury, because the comedy is the mode one cannot avoid in a novel. Bradbury asserts “the birth of the long prose tale was, then the birth of new vision of the human comedy and from that time it seems prose stories and comedy have never been far apart” (Bradbury, 1995: 2). The time when the novel prospers is the time of the development of the comic vision. The comic novelist Iris Murdoch in an interview in 1964 states that “in a play it is possible to limit one’s scope to pure tragedy or pure comedy, but the novel is almost inevitably an inclusive genre and breaks out of such limitations. Can one think of any great novel which is without comedy? I can’t.” According to Murdoch, the novel is the most ideal genre to adapt itself to tragicomedy. Moll Flanders is not a pure tragedy or pure comedy. On the one hand, it conveys a tragic and realistic view of life; on the other hand, tragic situations are recounted in a satirical way. Moll’s struggles to live, her subsequent marriages, her crimes for money are all expressed through parody. The aim of this study is to analyze 18th century social life, the comic scenes and especially the satire in the novel by describing the novel’s techniques of humor. -

The Mocking Mockumentary and the Ethics of Irony

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 8 December 2007 The oM cking Mockumentary and the Ethics of Irony Miranda Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Campbell, M. (2017). The ockM ing Mockumentary and the Ethics of Irony. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.31390/taboo.11.1.08 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterMiranda Campbell 2007 53 The Mocking Mockumentary and the Ethics of Irony Miranda Campbell “Shocking and Provocative.” “Death-defying satire.” “Edgy.” “A New Genre.” A quick survey of film critics’ reviews of Borat reveal language that is drenched in the rhetoric of innovation, avant-gardism, and subversion. The genre that Borat makes use of, the mockumentary, and is indeed generally seen as subversive, in that it undermines the documentary’s claim to objectively tell the truth. It is also a relatively new genre, that was spawned by the proliferation of available archival footage since the 1950s, but that has gained increasing popularity over the last 30 years, with This is Spinal Tap often cited as a key catalyzing film by directors and critics alike. As a genre, the mockumentary mobilizes irony, either in the parody of the form of the documentary or in the satirical treatment or critique of an issue. This mobilization can be relatively gentle and mild, such as parodies of the docu- mentary like The Ruttles that mockumentary theorists Jane Roscoe and Craig Hight identify as the first “level” of irony in the mockumentary. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays.