Pbs' "To the Contrary"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

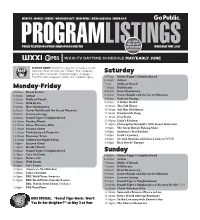

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

November At-A-Glance *Join Us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27

Original Concert Film Screening Fall Mystery Marathon— Series—page 9 Invitation—page 16 pages 17 & 18 Please visit wycc.org/schedule for the most current programming schedule. November at-a-glance *Join us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27. Please check the listings for a full schedule. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY* FRIDAY* SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00 AM Classical Stretch Curious George Curious George The Cat in the Hat The Cat in the Hat 6:30 Body Electric Knows a Lot Knows a Lot About About That! That! (except 11/1) Wai Lana Yoga Ribert & Robert’s Mister Rogers’ 7:00 WonderWorld Neighborhood Sit and Be Fit Angelina Ballerina: Bob the Builder 7:30 The Next Steps Barney & Friends Sid the Science Kid 8:00 Odd Squad 8:30 Wild Kratts Arthur Zula Patrol 9:00 Sesame Street Sesame Street Sesame Street Wunderkind Cyberchase 9:30 Peg + Cat (starting 11/16) Little Amadeus 10:00 Dinosaur Train DragonflyTV Biz Kid$ Mid-American In the Americas with 10:30 Curious George Gardener David Yetman Bob the Builder Garden Smart Pritzker Military 11:00 Presents Victory Garden’s 11:30 Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood (starting 11/16) EdibleFEAST PM P. Allen Smith’s Charlie Rose: 12:00 Super Why! Garden Home The Week Thomas & Friends This Old House Justice and Law 12:30 Weekly The Best of the Sewing with Nancy Well Read Quilting Arts The Beauty of The American Religion & Ethics 1:00 Joy of Painting Oil Painting Woodshop Newsweekly Wyland’s Art Studio Sew It All Between the Lines Fons & Porter’s Beads, Baubles, Hometime Closer to Truth 1:30 with Barry Kibrick Love of Quilting and Jewels Frank Clarke Simply Fit 2 Stitch Joseph Rosendo’s Knitting Daily The Donna The Woodwright’s Second Opinion 2:00 Painting Around the Travelscope Dewberry Show Shop World: China P. -

Wpsu.Org PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016

PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016 VOL. 46 NO. 2 PBS Best of Pledge Weekend... Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, February 5–7 Tune in for an entire of weekend of your favorites on WPSU, including these best-loved programs: TICKET OPPORTUNITY! Brit Floyd: Space and Time, Aging Backwards The Carpenters: Close to You Live in Amsterdam with Miranda Esmonde-White (My Music Presents) Brit Floyd pays special tribute to Pink Receive valuable insights on how to Trace the band's career, through the eyes Floyd and the era defining classic rock, combat the physical signs and of bandmates and friends, and favorites during their 2015 Space and Time tour. consequences of aging. such as "Top of the World". Friday, February 5, at 9:30 p.m. Saturday, February 6, at 3:00 p.m. Sunday, February 7, at 6:30 p.m. Make your pledge of support by calling 1-800-245-9779, or go online to wpsu.org. Democratic Presidential Ready Jet Go! Debate 2016: Advance Screening Event Saturday, February 13, at 1:00 p.m. A PBS NewsHour Special Report WPSU Studios, State College Thursday, February 11, at 9:00 p.m. The countdown has begun! Bring your little ones to WPSU for the Broadcast live from Milwaukee, Wisconsin launch of PBS Kids’ newest children’s series, Ready Jet Go! Join us just days after votes are cast in the New for an afternoon of out-of-this-world science activities, followed by Hampshire Primary and the Iowa Caucuses, interplanetary snacks and a preview screening of the first episode this will be the first time the candidates will in our television studio. -

Kuana Torres Kahele

PROGRAM GUIDE | SEPTEMBER 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 9 Kuana Torres Kahele The multi Nā Hōkū Hanohano-award winner brings his band to the PBS Hawai‘i studio STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chair Jason Haruki Vice Chair Ryan Kaipo Nobriga Secretary Have you ever been so late to a the introduction of portable digital Joy Miura Koerte party it feels like the carriages have audio playback devices in 2004 that Treasurer turned back into pumpkins, the podcasting really caught on. Kent Tsukamoto horses back to mice and the dresses back to rags? I’m not comparing On Friday, May 14, 2021, I asked our Muriel Anderson Jodi Endo Chai myself to Cinderella, especially since team, “How do we start a podcast?” James E. Duffy Jr. my size 11-wide feet would never Fast forward to August 11, 2021, when Matthew Emerson fit in any glass slipper, but that’s less than three months later PBS AJ Halagao how I felt when I first asked the Hawai‘i entered the podcast world Wilbert Holck PBS Hawai‘i Communications team with the first episode ofWhat Siana Hunt about podcasts. School You Went? This new weekly Noelani Kalipi Cheryl Ka‘uhane Lupenui podcast explores the traditions and Ian Kitajima Thankfully, no one laughed, stories that make up the modern-day Ashley Takitani Leahey although I did hear someone snort. culture of Hawai‘i. A special guest Kevin Matsunaga Instead, they welcomed me to the joins us each week to lend insight Theresia McMurdo podcast party and encouraged me and share personal stories about Bettina Mehnert Jeff Mikulina to stay awhile. -

Jaxpbs 7.4 JULY 2021 SCHEDULE

1 REV JUN 10 JaxPBS 7.4 JULY 2021 SCHEDULE 27-Jun-21 28-Jun-21 29-Jun-21 30-Jun-21 1-Jul-21 2-Jul-21 3-Jul-21 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 MISTER ROGERS I I I I I MISTER ROGERS 6:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 6:30 ARTHUR I I I I I ARTHUR 6:30 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 7:00 MOLLY OF DENALI I I I I I MOLLY OF DENALI 7:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 7:30 WILD KRATTS I I I I I WILD KRATTS 7:30 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 8:00 HERO ELEMENTARY I I I I I HERO ELEMENTARY 8:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 8:30 XAVIER RIDDLE AND I I I I I XAVIER RIDDLE AND 8:30 AM THE SECRET MUSEUM I I I I I THE SECRET MUSEUM NET I I I I I NET 9:00 CURIOUS GEORGE I I I I I CURIOUS GEORGE 9:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 9:30 DANIEL TIGER'S NEIGHBORHOOD I I I I I DANIEL TIGER'S NEIGHBORHOOD 9:30 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 10:00 DONKEY HODIE I I I I I DONKEY HODIE 10:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 10:30 ELINOR WONDERS WHY I I I I I ELINOR WONDERS WHY 10:30 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 11:00 SESAME STREET I I I I I SESAME STREET 11:00 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 11:30 PINKALICIOUS & PETERIFFIC I I I I I PINKALICIOUS & PETERIFFIC 11:30 AM I I I I I NET I I I I I NET 12:00 SPLASH AND BUBBLES NATURE PLANTS BEHAVING OZONE HOLE: HOW FOOD - DELICIOUS BIG PACIFIC SPLASH AND BUBBLES 12:00 PM 3602 BADLY WE SAVED THE PLANET SCIENCE 101 NET SUPER CATS: CATS 101 103 MYSTERIOUS NET 12:30 CYBERCHASE IN EVERY CORNER WE ARE WHAT WE EAT PT. -

September 2016 Program Guide

WTVPSeptember 2016 Program Guide Your WTVP Program Guide is a benefit of membership— thank you! Also visit wtvp.org 2 2 WTVP—More Choices Spotlight on Education Monday, September 12—Thursday, September 15 This special week of primetime programming features reports from today’s classrooms, examining how creativity and dedication to teaching all children, even the most challenging or at-risk students, makes a real For more difference in communities. It also underscores public media’s information, dedication to learning and the critical importance of convening please visit a dialogue around education. POV: All the Difference wtvp. org Monday, September 12, 9 p.m. W Accompany two African-Amer- ican teens from the South Side of Chicago on their journey to achieve their dream of graduat- ing from college. PBS explores the unseen elements that structure our FRONTLINE: A Subprime Education / The Education world in FORCES OF NATURE of Omarina A four-part PBS & BBC co-production premieres September 14 Tuesday, September 13, 8 p.m. at 7:00 p.m. FRONTLINE presents two films that build on its education reporting:“A The forces that have kept the Earth on the move since it was formed billions Subprime Education,” a fresh look at the troubled for-profit college industry, of years ago are explored in FORCES OF NATURE. In each of the four examines reports of predatory behavior and fraud and the implosion of the episodes, the series illustrates how we experience Earth’s natural forces, in- education chain, Corinthian Colleges. “The Education of Omarina” shows how cluding shape, elements, color and motion. -

Gamutjune2015 Greg

CATCH THE LATEST Let’s Polka! ePISODE The Piatkowski Brothers Part 2, June 13th at 6:30 pm on WSKG TV! WSKG/WSQX PROGRAM GUIDE JUNE 2015 MASTERPIECE’s Poldark Returns! Almost 40 years ago Captain Ross Poldark galloped across the TV screens of millions of PBS viewers in one of MATERPIECE’s earliest hit series, Poldark. The new Poldark, starring Aidan Turner (The Hobbit) airs in eight exciting episodes starting June 21st at 9:00 pm on WSKG TV. Aidan Turner as Ross Poldark WSKG TV Special Summer Programs Aging Backwards Country Pop Legends June 6th at 2:00 pm June 6th at 8:00 pm Join Miranda Esmond- Join host Roy Clark White as she shares her for a trip down three insights on combating decades of memory the physical signs of lane with country pop aging with exercise and legends. other lifestyle choices. Benise: Strings of Passion Last Tango in Halifax June 7th at 5:30 pm June 7th at 8:00 pm Enjoy the third season of this award-winning series that celebrates life and love. Virtuoso guitarist Benise takes you on an international journey of musical genres, including salsa, flamenco, tango, waltz, samba and more. WSKG HD Daytime WEEKDAYS SATURDAYS SUNDAYS 6:00am CAILLOU WORKPLACE ESSENTIAL SKILLS MISTER ROGERS’ NEIGHBORHOOD 6:30am ARTHUR KNITTING DAILY DANIEL TIGER’S NEIGHBORHOOD 7:00am ODD SQUAD QUILTING ARTS CURIOUS GEORGE 7:30am WILD KRATTS FIT 2 STITCH CURIOUS GEORGE 8:00am CURIOUS GEORGE SEWING WITH NANCY PEG + CAT 8:30am CURIOUS GEORGE SEW IT ALL SID THE SCIENCE KID 9:00am DANIEL TIGER’S NEIGHBORHOOD SESAME STREET (SHORTS) THIS OLD HOUSE -

Daytime Programs Sunday, April 1

Daytime Programs Sunday, April 1 Monday-Friday Line-Up 6:00 AM Mister Rogers 5:00 AM Wai Lana 6:30 Sid The Science Kid 5:30 Sit and Be Fit 7:00 Ready Jet Go! 6:00 Odd Squad 7:30 Wild Kratts 6:30 The Cat In The Hat 8:00 NatureCat 7:00 Nature Cat 8:30 Odd Squad 7:30 Curious George 9:00 Arthur 8:00 Pinkalicious & Peterrific 9:30 Cyberchase 8:30 Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 10:00 Latina Voices: Smart Talk 9:00 Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 10:30 To The Contrary 9:30 Splash and Bubbles 11:00 Motorweek 10:00 Sesame Street 11:30 This Old House 10:30 Super Why! 12:00 Ask This Old House 11:00 Dinosaur Train 12:30 Scitech Now 11:30 Peg + Cat 1:00 PM Search For The Last Supper NOON Sesame Street 2:00 Rick Steves Special 12:30 Ready Jet Go! European Easter 1:00 Curious George 1:30 Nature Cat 2:00 Nature Cat 2:30 Wild Kratts 3:00 Wild Kratts 3:30 Odd Squad 4:00 Odd Squad 4:30 Arthur 5:00 BBC World News America 5:30 Nightly Business Report 6:00PM PBS Newshour 3:00 1916 The Irish Rebellion: Awakening HOUSTON PUBLIC MEDIA TV 8 PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE — April 2018 PAGE 1 Narrated by actor Liam Neeson, the series 1916 The Monday, April 2 Irish Rebellion tells the dramatic story of the events 7:00 PM Antiques Roadshow: Portland that took place in Dublin during Easter of 1916, 8:00 Antiques Roadshow: Little Rock when a small group of poorly-armed Irish rebels took on the might of the British Empire. -

Wpsu.Org PROGRAM GUIDE JULY 2016

PROGRAM GUIDE JULY 2016 VOL. 46 NO. 7 WPSU-FM and Monthly, beginning Palmer Museum of Art present... Thursday, July 28 For each concert, doors will open to the Palmer Lipcon Auditorium at 7:00 p.m., and performances will begin at 7:30 p.m. Attendance is FREE and limited to four 2016 Concert Dates seats per address. July 28 Eddie Severn Quartet Reservations for each concert will open at 8:00 a.m. on the first day of the month August 25 Rick Hirsch 3 of the concert. September 22 Ryan Kauffman Trio October 27 Penn State Student Ensemble wpsu.org/jazzatthepalmer Our Town Marathon Featuring: Port Allegany, Somerset, PBS Convention Coverage – Brockway, Johnsonburg, and Geistown A NewsHour Special Report Monday, July 4, 12:00 p.m.–4:30 p.m. Republican National Convention: Experience for yourself what makes each of these small July 18–21, 8:00–11:00 p.m. nightly towns such a great place to live, through stories of history, Democratic National Convention: culture, and community ties as told by their residents. July 25–28, 8:00–11:00 p.m. nightly Veteran journalists Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff anchor complete live coverage of both national Children and Youth Day political conventions, from opening gavel to official at the Arts Festival close, including interviews from newsmakers, Wednesday, July 13, 10:00 a.m.–3:00 p.m. analysis and perspective, plus insights from presidential historians and others. Visit the WPSU tent on Old Main Lawn during the Central Pennsylvania Festival of the Arts for a craft activity, and a meet and greet with Jet Propulsion from PBS Kids’ Ready Jet Go! We hope to see you there! wpsu.org follow us online NEW THIS MONTH ON WPSU-TV The Great British Baking Show MONDAY–FRIDAY Fridays, July 1–29, at 9:00 p.m. -

Highlights November 2020

Highlights November 2020 Inside Balmoral Rick Steves Egypt: Freedom Summer: Sunday, November 1 from 8 p.m. to 11 p.m. Yesterday and Today American Experience Discover the dramatic moments and histor- Friday, November 6 at 9 p.m. Monday, November 30 at 9 p.m. ical events that occurred within the walls Join Rick Steves as he explores the wonders Revisit the hot and deadly summer of 1964, of Scotland’s Balmoral Castle as Queen of Egypt: cruising on the Nile; the cultural when student volunteers and local Black Elizabeth and her family lived there. treasures of Cairo, Luxor, and Abu Simbel; citizens faced racial violence in Mississippi and the back lanes of Alexandria. while registering voters in an attempt to break the hold of segregation. SATURDAYS 11/7 11/14 11/21 11/28 •AM• •AM• •AM• •AM• 12:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 12:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 12:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 12:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 2:30 TO THE CONTRARY 1:30 BEYOND THE CANVAS 2:30 TO THE CONTRARY 1:30 BEYOND THE CANVAS 3:30 WASHINGTON WEEK 2:00 TO THE CONTRARY 3:30 WASHINGTON WEEK 2:00 TO THE CONTRARY 4:00 FIRING LINE 3:00 WASHINGTON WEEK 4:00 FIRING LINE 3:00 WASHINGTON WEEK 4:30 FUTURE OF AMERICA’S PAST 3:30 FIRING LINE 4:30 RICK STEVES SPECIAL 3:30 FIRING LINE 5:00 FUTURE OF AMERICA’S PAST 4:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 5:30 UNTAMED 4:00 GREAT PERFORMANCES 5:30 FUTURE OF AMERICA’S PAST 5:30 BEYOND THE CANVAS 6:00 CHILDREN’S PROGRAMMING 5:30 VIRGINIA CURRENTS 6:00 CHILDREN’S PROGRAMMING 6:00 CHILDREN’S PROGRAMMING 6:00 CHILDREN’S PROGRAMMING •PM• •PM• •PM• 4:00 THIS OLD HOUSE •PM• 4:00 -

September 2016

MAGAZINE September 2016 “Masterpiece: Poldark Season 2” Premieres Sunday, Sept. 25, at 7 p.m. Against the breathtaking back- drop of 18th century Cornwall, Aidan Turner (Poldark), Eleanor Tomlinson (Demelza) and Heida Reed (Elizabeth) return as the complicated love triangle in a new season of the popular romantic saga, based on the novels by Winston Graham. A Magazine for the Supporters of the AETN Foundation From the Director AETN Productions Dear Friend, students learn and thrive. In its 10-year existence, ArkansasIDEAS has grown into arguably the larg- Many people think est free (to educators) service in the country. “Exploring Arkansas” of AETN as “just” a Lake Greeson in Southwest Arkansas has long been known for its great crappie fishing. Catching “slab” TV station. While we AETN PBS LearningMedia, a free service for all crappie in the 17-inch category is not out of the norm. Along North Sylamore Creek near Mountain View, are justifiably proud teachers, students and home-schooling families, is near the North Sylamore Creek Trailhead, is a secluded swimmin’ hole complete with a rope swing that is of our wonderful another example of service beyond a terrific pro- quite popular with the locals. Jacksonville Museum of Military History sits and diverse program gram schedule. This service includes classroom- on the old Arkansas Ordnance Plant site, which manufactured bomb parts schedule, education ready, curriculum-based, digital resources, includ- during WWII. She’s known to many as the pie queen of the South – meet is at the heart of our mission at AETN and PBS. ing videos and interactives, audio, documents and Charlotte Bowls of Keo who creates her 10-inch high meringue pies in a AETN was created to use the power of media to in-depth lesson plans. -

From the Fields to the Streets to the Stage: Chicana Agency

FROM THE FIELDS TO THE STREETS TO THE STAGE: CHICANA AGENCY AND IDENTITY WITHIN THE MOVIMIENTO by ERIN CAROL ANASTASIA MOBERG A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Romance Languages and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Erin Carol Anastasia Moberg Title: From the Fields to the Streets to the Stage: Chicana Agency and Identity Within the Movimiento This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Romance Languages by: Analisa Taylor Chairperson Amalia Gladhart Core Member Evlyn Gould Core Member Theresa May Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2015. ii © 2015 Erin Carol Anastasia Moberg iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Erin Carol Anastasia Moberg Doctor of Philosophy Department of Romance Languages December 2015 Title: From the Fields to the Streets to the Stage: Chicana Agency and Identity Within the Movimiento The unionization of the United Farm Workers in 1962 precipitated the longest labor movement in US history, which in turn inspired all sectors of Chicana/o activism and artistic production. As the Movimiento gained support and recognition throughout the 1960s, grassroots and activist theater and performance played fundamental roles in representing its causes and goals. By the 1980s, however, the Movimiento was frequently represented and understood as a reclaiming of Chicano identity through an assertion of Chicano masculinity, a reality which rendered the participation and cultural production of Chicanas even less visible within an already marginalized cultural and historical legacy.