Building Urban Safety Through Slum Upgrading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kibera: the Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin

Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin To cite this version: Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin. Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa?. Les Cahiers de l’Afrique de l’Est, 2011, 44, pp.23-34. halshs-00751833 HAL Id: halshs-00751833 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00751833 Submitted on 14 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes and Sophie Taupin Abstract This article presents the findings of the estimated population of Kibera, often said to be the “biggest slum in Africa”. This estimation was done in 2009 by the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA) Nairobi and Keyobs, a Belgian company, using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) methodology and a ground survey. The results showed that there are 200,000 residents, instead of the 700,000 to 1 million figures which are often quoted. The 2009 census and statistics on Kibera’s population also confirmed that the IFRA findings were accurate. Introduction Kibera, the infamous slum in Nairobi – Kenya’s capital, is viewed as “the biggest, largest and poorest slum in Africa”. -

Slum Toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya a Case Study Analysis of Kibera

Urban and Regional Planning Review Vol. 4, 2017 | 21 Slum toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya A case study analysis of Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru Melissa Wangui WANJIRU*, Kosuke MATSUBARA** Abstract Urban informality is a reality in cities of the Global South, including Sub-Saharan Africa, which has over half the urban population living in informal settlements (slums). Taking the case of three informal settlements in Nairobi (Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru) this study aimed to show how names play an important role as urban landscape symbols. The study analyses names of sub-settlements (villages) within the slums, their meanings and the socio-political processes behind them based on critical toponymic analysis. Data was collected from archival sources, focus group discussion and interviews, newspaper articles and online geographical sources. A qualitative analysis was applied on the village names and the results presented through tabulations, excerpts and maps. Categorisation of village names was done based on the themes derived from the data. The results revealed that village names represent the issues that slum residents go through including: social injustices of evictions and demolitions, poverty, poor environmental conditions, ethnic groupings among others. Each of the three cases investigated revealed a unique toponymic theme. Kibera’s names reflected a resilient Nubian heritage as well as a diverse ethnic composition. Mathare settlements reflected political struggles with a dominance of political pioneers in the village toponymy. Mukuru on the other hand, being the newest settlement, reflected a more global toponymy-with five large villages in the settlement having foreign names. Ultimately, the study revealed that ethnic heritage and politics, socio-economic inequalities and land injustices as well as globalization are the main factors that influence the toponymy of slums in Nairobi. -

'Pushing the Week' an Ethnography on The

‘PUSHING THE WEEK’ AN ETHNOGRAPHY ON THE DYNAMICS OF IMPROVING LIFE IN KIBERA: THE INTERPLAY OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES THESIS MSC DEVELOPMENT AND RURAL INNOVATION WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY AND RESEARCH CENTRE THE NETHERLANDS KEYWORDS SLUM, NGO’S, UPGRADING, GRASSROOTS, UPWARD MOBILITY, IMPROVEMENT, AGENCY, INFORMALITY, TRIBALISM, SPATIALITY, ETHNOGRAPHY STUDENT EVA VAN IWAARDEN STUDENT NUMBER 870712-383060 [email protected] SUPERVISOR DR. B.J. JANSEN SOCIOLOGY OF DEVELOPMENT AND CHANGE [email protected] ABSTRACT The title of this research starts with ‘pushing the week’. This is the translation of the most eaten vegetable in Kenya and Kibera, a kale by the name of ‘sukuma wiki’ in Swahili. As this research progressed and life in Kibera was examined more closely, it seems that language around life and living in Kibera can be seen closely related to the name of this vegetable that is eaten almost every day. ‘We are just pushing ahead in life, another week, lets see where it takes us’. No matter what is written down about life in Kibera, another week starts, and another one, and another one… This research examines how women living in Kibera perceive improvement of life in Kibera. This topic is very dynamic, broad and has many ways in which it can be approached. It is impossible to merely ask some questions and draw conclusions about a space so dynamic and a population in all its diversity. As most slums worldwide, Kibera is a popular place for organisations to lend a helping hand, where community initiatives are plenty and where slum upgrading programs are implemented. -

El Documentalismo Contemporáneo Brasileño 8

Página 1 de 168 PERSPECTIVA ANALÍTICA TERCERA PARTE: EL DOCUMENTALISMO CONTEMPORÁNEO BRASILEÑO 8. LA REALIDAD A TRAVÉS DE LA IMAGEN: FOTOGRAFÍA Y SOCIEDAD Las determinantes del documentalismo brasileño (Los fotógrafos extranjeros – La influencia de la formación étnica – La gran extensión territorial) – El desarrollo del documentalismo contemporáneo brasileño (La reflexión documental: años setenta – Los acontecimientos políticos: años ochenta – La expansión documental: años noventa) - Documentalismo contemporáneo brasileño: reflexiones formales (Hacia una tipología del documentalismo contemporáneo brasileño – Hacia una clasificación de los documentalistas contemporáneos brasileños) – Análisis de los documentalistas contemporáneos brasileños Orlando Brito, Ceará, década de 1980 "La visión es la función natural del fotógrafo, lo que parece obvio. En su forma menos pretenciosa de abordar el sujeto, busca describirlo visualmente. Muchos dan a eso el calificativo de documentación. Pero una fotografía no puede estar disociada de su autor, e incluso siendo descriptiva se trata de la descripción hecha por un determinado autor. Toda fotografía es una interpretación". Zé de Boni, fotógrafo file://D:\panalitica.htm 25/02/2003 Página 2 de 168 8. La realidad a través de la imagen: fotografía y sociedad 8.1. Las determinantes del documentalismo brasileño 8.1.1. Los fotógrafos extranjeros Desde la década de 1930 podemos encontrar buenos ejemplares de la fotografía documental en Brasil, aunque este estilo empezó a consolidarse en los años cincuenta y -

The Asylum Photographs of Claudio Edinger

Revista Digital do e-ISSN 1984-4301 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da PUCRS http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/letronica/ Porto Alegre, v. 12, n. 3, jul.-set. 2019: e35337 https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2019.3.35337 Unhiding hidden urban madness: the asylum photographs of Claudio Edinger 1 Regent Professor of Spanish and women and Desvendando a loucura escondida da cidade: as fotografias do hospício de Claudio Edinger gender studies at Arizona State University. He has written extensively on Argentine narrative and theater, Des-cubrindo la locura mental urbana: la fotografía de asilo de Claudio Edinger and he has held Fulbright teaching appointments in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. He has also served as an Inter-American Development Bank professor 1 in Chile. Foster has held visiting appointments at David William Foster Fresno State College, Vanderbilt University, University Arizona State University, School of International Letters and Cultures, Tempe, Arizona, The United States of America. of California-Los Angeles, University of California- Riverside, and Florida International University. He has conducted six seminars for teachers under the auspices of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the ABSTRACT: most recent in São Paulo in summer 2013. Mental illness is an inescapable component of urban life. The Brazilain photographer Claudio Edinger devotes one of his major photobooks to a study http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8807-4957 E-mail: [email protected]. of the São Paulo mental asylum, Jaqueri. This essay analyses the strategies of his analytical scrutiny of mental patients, with reference to associated ethical issues. Of particular interest is, necessarily, his emphasis on the body and its valid photographic representation. -

Download Malicious Software That Sends out Sensitive Data

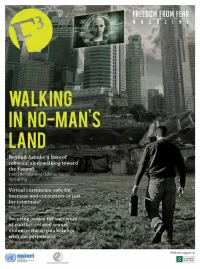

Freedom From Fear Magazine Special Edition including a limited selection of articles from this year’s issues Walking in no-man’s land freedomfromfearmagazine.org [email protected] unicri.it With the support of Nobody’s going to fix the world for us, but working together, making use of technological innovations and human communities alike, we might just be able to fix it ourselves Jamais Cascio Editorial Board UNICRI Jonathan Lucas Marina Mazzini Max-Planck Institute Hans-Jörg Albrecht Ulrike Auerbach Michael Kilchling Editorial Team Fabrizio De Rosa Marina Mazzini Maina Skarner Valentina Vitali Graphic and layout Beniamino Garrone Website designer Davide Dal Farra Disclaimer The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and positions of the United Nations. Authors are not responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. Contents of the publication may be quoted or reproduced, provided that the source of information is ack- nowledged. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations and UNICRI, concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific institutions, companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the Secretariat of the United Nations or UNICRI in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

LAA131010V7:Latin America Advisor.Qxd

www.thedialogue.org Thursday, October 10, 2013 FEATURED Q&A BOARD OF ADVISORS Has the Government Shutdown Eroded U.S. Credibility? Diego Arria James R. Jones Director, Co-chair, Approximately 450,000 U.S. gov- impossible to understand. This could not Columbus Group Manatt Jones ernment employees remain fur- come at a worse time, amid the Brazil spy- Global Strategies LLC loughed as the U.S. government ing scandal, the embattled new government Genaro Arriagada shutdown enters its tenth day in Venezuela and the historic opportunity Nonresident Senior Craig A. Kelly Q amid Congress' failure to reach agreement we have to build a stronger relationship Fellow, Director, Americas Inter-American International Gov't on a spending bill. How might the shut- with the new president of Mexico, Enrique Dialogue Relations, down affect trade and other cross-border Peña Nieto. As a Republican and former Joyce Chang Exxon Mobil transactions between the United States business leader before serving as secretary and Latin American countries? What types of commerce, I am alarmed by the lack of a Global Head of John Maisto Emerging Markets Director, of U.S. negotiations, forums, visits or meet- coherent strategy by my party. No institu- Research, JPMorgan U.S. Education Finance ings with counterparts in Latin America tion can be managed by emotion and tac- Chase & Co. Group will be disrupted? Has Washington's polit- tics, let alone a $4 trillion federal govern- W. Bowman Cutter Nicolás Mariscal ical paralysis eroded U.S. credibility ment. However, this is precisely what is Former Partner, Chairman, among the Latin Americans who have E.M. -

6. Panorama Histórico-Geográfico

SEGUNDA PARTE: LA FOTOGRAFÍA DOCUMENTAL EN BRASIL (Capítulos 6 y 7) 6. PANORAMA HISTÓRICO-GEOGRÁFICO Brasil: historia y geografía (Reseña histórica - Datos socioeconómicos, políticos y culturales - Distribución y características de las cinco regiones) - La fotografía brasileña del siglo XIX (Hércules Florence: un descubridor aislado - Las demostraciones del abad Louis Compte - Don Pedro II: un aficionado y mecenas de la fotografía - Los fotógrafos pioneros) - La fotografía pictorialista en Brasil - La ruptura de las artes con el pasado - La fotografía moderna en Brasil Hermínia Nogueira Borges, Instrução Divulgada, 1926. Gelatina de plata. Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Río de Janeiro. "Sin el hábito y la memoria de la experiencia pasada, ninguna visión o sonido significarían alguna cosa; podemos percibir solamente aquello a lo que estamos acostumbrados". Lowenthal, 1985, 39 6. Panorama histórico-geográfico 6.1. Brasil: historia y geografía Mientras realizaba este trabajo sentí la necesidad de acercar la realidad brasileña al lector y a la mirada europea. Para esto hice una breve aproximación, intentando dar una visión general de un país tan complejo. Intento buscar la neutralidad, haciendo hincapié en aclarar viejos mitos. Ofrecer una reseña histórica, mostrar la distribución geográfica de las regiones brasileñas y sus principales características es esencial para la comprensión de muchos hechos ocurridos en la fotografía del país. La influencia regional y cultural en la visión fotográfica de muchos autores es destacable. Tampoco está de más recordar la historia, la geografía y los datos socioculturales a los lectores nativos. Muy al contrario, la conciencia histórico-cultural del país necesita ser reforzada. Brasil está caracterizado por su gran extensión de tierras, su clima tropical y sus contrastes económicos. -

Affordable Housing Provision in Informal Settlements Through Land

sustainability Article Affordable Housing Provision in Informal Settlements through Land Value Capture and Inclusionary Housing Bernard Nzau * and Claudia Trillo School of Science, Engineering and Environment, University of Salford, Manchester M5 4WT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 18 July 2020; Published: 24 July 2020 Abstract: Public-driven attempts to provide decent housing to slum residents in developing countries have either failed or achieved minimal output when compared to the growing slum population. This has been attributed mainly to shortage of public funds. However, some urban areas in these countries exhibit vibrant real estate markets that may hold the potential to bear the costs of regenerating slums. This paper sheds light on an innovative hypothesis to achieve slum regeneration by harnessing the real estate market. The study seeks to answer the question “How can urban public policy facilitate slum regeneration, increase affordable housing, and enhance social inclusion in cities of developing countries?” The study approaches slum regeneration from an integrated land economics and spatial planning perspective and demonstrates that slum regeneration can successfully be managed by applying land value capture (LVC) and inclusionary housing (IH) instruments. The research methodology adopted is based on a hypothetical master plan and related housing policy and strategy, aimed at addressing housing needs in Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi, Kenya. This simulated master plan is complemented with economic and residual land value analyses that demonstrate that by availing land to private developers for inclusionary housing development, it is possible to meet slum residents’ housing needs by including at least 27.9% affordable housing in new developments, entirely borne by the private sector. -

The Julia Dean Photo Workshops Expanding Photography in Southern California

The Julia Dean Photo Workshops Expanding Photography in Southern California Now Offering One-Week Intensives Winter/Spring 2010 B:9.25” T:7.75” S:7” B S T : : : 1 9 1 0 . 1 7 . 5 5 5 ” ” ” With 21.1 megapixels and Full HD video, it·s time to think bigger. The Canon EOS 5D Mark II. The world·s only camera to combine a 21.1 megapixel full-frame CMOS sensor with Full HD 1080p video. Giving you the power to combine breathtaking stills with revolutionary video. The industry has changed forever. Inspired. By Canon. To see more HD videos, visit usa.canon.com/dlc ©2009 Canon U.S.A., Inc. Canon and EOS are registered trademarks of Canon Inc. in the United States. IMAGEANYWARE is a trademark of Canon. LCD image simulated. All rights reserved. ©2008 Vincent Laforet, Canon Explorer of Light. 777 THIRD AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10017 THIS ADVERTISEMENT PREPARED BY GREY WORLDWIDE JOB #: 062-CM-118_Rev1 PROOF: 12 CLIENT: Canon USA Inc. SIZE, SPACE: 7.75” x 10.5”, 4CB CLIENT: Canon USA Inc. OP: WB, KW, ED, KW, JS, KW, WB PRODUCT: Camera Division-Lens/Shutter PUBS: Magazine SPACE/SIZE: B: 9.25” x 11.5” T: 7.75” x 10.5” S: 7” x 9.75” JOB#: 062-CM-118_Rev1 ISSUE: 2009 LEGAL RELEASE STATUS AD APPROVAL ART DIRECTOR: E. King COPYWRITER: None DATE: Release has been obtained Legal Coord: Acct Mgmt: Print Prod: Art Director: Proofreader: Copywriter: Studio: TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Staff Information . .1 Index by Topic . .2 NEW WORKSHOPS IN Index by Month . -

Toponymy and the Spatial Politics of Power on the Urban Landscape of Nairobi, Kenya

Toponymy and the Spatial Politics of Power on the Urban Landscape of Nairobi, Kenya March 2018 WANJIRU Melissa Wangui i Toponymy and the Spatial Politics of Power on the Urban Landscape of Nairobi, Kenya Graduate School of Systems and Information Engineering University of Tsukuba March 2018 WANJIRU Melissa Wangui ii ABSTRACT Names of places, otherwise known as toponyms, have in the past been viewed as passive signifiers on the urban space. However, in the last two decades, scholarly attention has focused on reading toponyms within the broader socio-political context — a concept referred to as critical toponymy. Critical toponymy refutes the notion that place names are simple, predictable and naturally occurring features which give descriptions of locations of places. In Nairobi, no critical research has been done to find out the motivations behind place naming and the implications of certain naming patterns, especially in showing the linkage between the power struggles and the toponymic inscriptions on the urban landscape. The main objective of this study is to investigate the meaning and processes behind the inscription of place names and their role in the spatial politics of power on the urban landscape of Nairobi, Kenya. To analyse toponymy and the spatial politics that influenced the city over time, Nairobi’s toponymic history was analysed chronologically based on three political epochs: the colonial period 1899–1963; the post-independence period 1964–1990; and the contemporary period 1990–2017. The third period was further sub-divided into two phases, with its latter phase starting in 2008, the year when the debate surrounding privatisation of naming rights began. -

A Cost of the Diet Assessment for Kibera

A Cost of the Diet analysis in the informal settlement of Kibera, Nairobi Location: Kibera Date collected: 15th – 19th July, 2013 HEA data: June 2013 1 Acknowledgments The Cost of the Diet analysis was led by Assumpta Ndumi from Save the Children UK, with support from Catherine Syombua and Peter Kagwemi of Umande Trust who provided administrative and logistical support. The Cost of the Diet assessment was undertaken by: Teresiah Wairimu, Sherry Hadondi, David Githinji, Susan Mumbua, Stella Nabwire, Elizabeth Muthikwa, Irene Abuto, Dorothy Ambogo and Victor Otieno. The analysis and this report were written by Assumpta Ndumi with contributions from Amy Deptford. The analysis was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. Thanks to due to Save the Children staffs from the Kenya country office, EA regional office and London for their support and for making the practical arrangements for the analysis to take place. This analysis would not have been possible without the willing help of the market traders of Laini Saba, Soweto East, Gatwekera, Makina, Kisumu Ndogo, Mashimoni, Kianda and Silanga and of the women who participated in the focus group discussions. Their time, hospitality and insights are greatly appreciated. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 3 List of tables and figures ................................................................................................