A Road Map for 21St Century Geography Education Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touring Exhibitions Programme 2020 – 22

touring exhibitions programme 2020 – 22 designmuseum.org Design Museum Touring Programme Contents The programme was set up in 2002 with the aim of bringing Exhibitions design exhibitions to audiences around the UK and internationally. 4 Material Tales Since then, the museum has organised more than 130 tours to 6 Sneakers Unboxed 104 venues in 31 countries worldwide. 8 Waste Age 10 Football The Design Museum’s touring exhibitions range in size from 12 Got to Keep On 150 to 1000 square metres and encompass all areas of design – 14 Moving to Mars architecture, fashion, graphics, product, digital and more. 16 Breathing Colour by Hella Jongerius 18 Exhibition Catalogues About the Design Museum 24 Terms and Conditions 25 Contacts The Design Museum is the world’s leading museum devoted to architecture and design. Its work encompasses all elements of design, including fashion, product and graphic design. Since it opened its doors in 1989, the museum has displayed everything from an AK-47 to high heels designed by Christian Louboutin. It has staged over 100 exhibitions, welcomed over five million visitors and showcased the work of some of the world’s most celebrated designers and architects including Paul Smith, Zaha Hadid, Jonathan Ive, Miuccia Prada, Frank Gehry, Eileen Gray and Dieter Rams. On 24 November 2016, the Design Museum relocated to Kensington, West London. Architect John Pawson converted the interior of a 1960s modernist building to create a new home for the Design Museum, giving it three times more space in which to show a wider range of exhibitions and significantly extend its learning programme. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Analysing the Characteristics of Major

TR ƯỜNG ĐẠ I H ỌC S Ư PH ẠM TP H Ồ CHÍ MINH HO CHI MINH CITY UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION TẠP CHÍ KHOA H ỌC JOURNAL OF SCIENCE ISSN: KHOA H ỌC GIÁO D ỤC EDUCATION SCIENCE 1859-3100 Tập 15, S ố 1 (2018): 182-191 Vol. 15, No. 1 (2018): 182-191 Email: [email protected]; Website: http://tckh.hcmue.edu.vn ANALYSING THE CHARACTERISTICS OF MAJOR BRANCHES OF MODERN GEOGRAPHY Tran The Dinh *, Nguyen Thi Thanh Nhan Department of Geography, An Giang University Received: 29/9/2017; Revised: 09/10/2017; Accepted: 22/01/2018 ABSTRACT Geography can be described as a field of science which is the study of the Earth’s physical features, people, as well as the relationships between people and their environment. Based on collecting and analyzing materials from various sources, the paper analyze the characteristics of major branches in the new trend of geography. In addition, as a basis for the above analysis, we also outline the history of geography and present the traditional and modern methods in geographical research. Keywords: branches of geography, history of geography, methods in geographical research, geography. TÓM T ẮT Phân tích đặc điểm các nhánh nghiên c ứu chính c ủa địa lí học hi ện đại Địa lí học được miêu t ả là m ột ngành khoa h ọc, nghiên c ứu v ề đặc điểm t ự nhiên trên b ề mặt Trái Đất, nghiên c ứu v ề con ng ười c ũng nh ư m ối quan h ệ gi ữa con ng ười v ới môi tr ường sinh s ống của h ọ. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

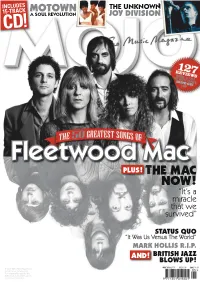

Mojoearlier Results Are Tremendous

INCLUDES MOTOWN THE UNKNOWN 15-TRACK A SOUL REVOLUTION JOY DIVISION CD! Y PLUS! HE MAC NOW! “It’s a miracle that we survived” STATUS QUO MARK HOLLIS R.I.P. AND! BRITISH JAZZ BLOWS UP! MAY 2019 £5.75 US$11.99 CAN$14.99 If your CD is missing please inform your newsagent. For copyright reasons the CD is not available in some overseas territories. Lias Saoudi, torch-carrying FILTER ALBUMS provocateur. These New hypnosis rule, though, remains town (the New York strut of duet of self-destruction. After to be seen. Enlightening 2017’s City Music). With Oh My all of it, JPW is left at the sink, Puritans nevertheless. God, Morby launches a more repeating, “Your love’s the ★★ Charles Waring overtly spiritual quest, hurting kind,” unable or investigating the tensions unwilling to give it up. Inside The Rose between the sacred and Chris Nelson INFECTIOUS MUSIC. CD/DL/LP profane – or “horns on my Underwhelming fourth Our Native head, wings from my album from Southend Daughters shoulder,” as he puts it on The Cranberries erstwhile avant-garde ★★★★ O Behold. A blast of Mary world-beaters Lattimore’s harp on Piss River #### SongsOfOur or Savannah’s glassy Dirty Slimmed down In The End Native Daughters Projectors-style choir hint at to the core the celestial, but if Morby BMG. CD/DL/LP fraternal duo SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS. CD/DL Edwyn Collins speaks in tongues, they are still Final album, with Step of Jack and New history from onet very much those of Bob Dylan #### Street back producing George Barnett leader of the Carolina and Leonard Cohen – earthly, after the 2016 Chocolate Drops. -

Fifty Years of Historical Geography in Canada 5

Fifty Years of Historical Geography in Canada 5 ‘Tracing One Warm Line Through a Land so Wide and Savage’. Fifty Years of Historical Geography in Canada Graeme Wynn Department of Geography University of British Columbia ABSTRACT: In this essay I enlist Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers to provide a title and a structure for inevitably personal reflections on the scholarly contributions of Canadian historical geographers and the changing fortunes of historical geography in their country since the 1960s. From the “Northwest Passage” (“one warm line…”) to “Make and Break Harbour” (where “the boats are so few”) this is a tale of considerable achievement, but one that, may lack a particularly happy or optimistic ending unless we attend to “The Field Behind the Plow” (and “Put another season’s promise in the ground”). Because this story, however told, bears the marks of influence from the United Kingdom, the United States and elsewhere, this essay speaks to developments beyond the territory of Canada and the geographical interests of those who live within its borders. Like several of Rogers’ songs, it might also be considered something of a parable. hen Robert Wilson invited me to give the fourth HGSG distinguished lecture he observed: “You may speak on whatever topic you like. It could be about some aspect Wof your current research or about the state of historical geography (or both).” In the end I decided to do both – and more. To structure the inevitable jumble spilling from this great portmanteau I make two moves. First I focus my comments on historical geography in Canada since the late 1960s. -

Album of the Year Record of the Year

Album of the Year I, I Bon Iver NORMAN F—ING ROCKWELL! Lana del Rey WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO? Billie Eilish THANK U, NEXT Ariana Grande I USED TO KNOW HER H.E.R. 7 Lil Nas X CUZ I LOVE YOU Lizzo FATHER OF THE BRIDE Vampire Weekend Record of the Year HEY MA Bon Iver BAD GUY Billie Eilish 7 RINGS Ariana Grande HARD PLACE H.E.R. TALK Khalid OLD TOWN ROAD Lil Nas X ft. Billy Ray Cyrus TRUTH HURTS Lizzo SUNFLOWER Post Malone Song of the Year ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY Natalie Hemby, Lady Gaga, Hillary Lindsey and Lori McKenna, songwriters (Lady Gaga) BAD GUY Billie Eilish O’Connell & Finneas O’Connell, songwriters (Billie Eilish) BRING MY FLOWERS NOW Brandi Carlile, Phil Hanseroth, Tim Hanseroth and Tanya Tucker, songwriters (Tanya Tucker) HARD PLACE Ruby Amanfu, Sam Ashworth, D. Arcelious Harris, H.E.R. & Rodney Jerkins, songwriters (H.E.R.) LOVER Taylor Swift NORMAN F***ING ROCKWELL Jack Antonoff and Lana del Ray, songwriters (Lana del Rey) SOMEONE YOU LOVED Tom Barnes, Lewis Capaldi, Pete Kelleher, Benjamin Kohn and Sam Roman, songwriters (Lewis Capaldi) TRUTH HURTS Steven Cheung, Eric Frederic, Melissa Jefferson and Jesse Saint John, songwriters (Lizzo) Best New Artist BLACK PUMAS BILLIE EILISH LIL NAS X LIZZO MAGGIE ROGERS ROSALíA TANK AND THE BANGAS YOLA Best Pop Solo Performance SPIRIT Beyoncé BAD GUY Billie Eilish 7 RINGS Ariana Grande TRUTH HURTS Lizzo YOU NEED TO CALM DOWN Taylor Swift Best Pop Duo/Group Performance BOYFRIEND Ariana Grande & Social House SUCKER Jonas Brothers OLD TOWN ROAD Lil Nas X Featuring Billy -

Impact of a Geography-Literature Collaborative on Secondary School Pedagogy John Matthew Cm Cormick Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Impact of a Geography-Literature Collaborative on Secondary School Pedagogy John Matthew cM Cormick Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Education Commons, and the Geography Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Education This is to certify that the doctoral study by John Matthew McCormick has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Heather Caldwell, Committee Chairperson, Education Faculty Dr. Jesse Richter, Committee Member, Education Faculty Dr. Barbara Schirmer, University Reviewer, Education Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2019 Abstract Impact of a Geography-Literature Collaborative on Secondary School Pedagogy by John Matthew McCormick MLS, West Virginia University, 2012 M.Ed., Concord University, 2010 BA, Concord University, 2005 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Walden University April 2019 Abstract Geography education has been relegated to a subset of social studies standards in most of the United States and has been overshadowed by a history-centered curriculum. Student achievement in geography has not improved for several decades due to the focus on history content in the social studies curriculum. -

Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Edited by Peter Ludlow

Ludlow cover 7/7/01 2:08 PM Page 1 Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Crypto Anarchy, Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias edited by Peter Ludlow In Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, Peter Ludlow extends the approach he used so successfully in High Noon on the Electronic Frontier, offering a collection of writings that reflect the eclectic nature of the online world, as well as its tremendous energy and creativity. This time the subject is the emergence of governance structures within online communities and the visions of political sovereignty shaping some of those communities. Ludlow views virtual communities as laboratories for conducting experiments in the Peter Ludlow construction of new societies and governance structures. While many online experiments will fail, Ludlow argues that given the synergy of the online world, new and superior governance structures may emerge. Indeed, utopian visions are not out of place, provided that we understand the new utopias to edited by be fleeting localized “islands in the Net” and not permanent institutions. The book is organized in five sections. The first section considers the sovereignty of the Internet. The second section asks how widespread access to resources such as Pretty Good Privacy and anonymous remailers allows the possibility of “Crypto Anarchy”—essentially carving out space for activities that lie outside the purview of nation-states and other traditional powers. The Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, third section shows how the growth of e-commerce is raising questions of legal jurisdiction and taxation for which the geographic boundaries of nation- states are obsolete. The fourth section looks at specific experimental governance and Pirate Utopias structures evolved by online communities. -

University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor. Michigan

72-4425 BLOOMER, Francis Eldon, 1925- SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHERS* PERCEPTION OF TOPICS IN GEOGRAPHY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, general U n iv e rs ity M ic ro film s . A XEROXCompany , Ann Arbor. Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHERS' PERCEPTION OF TOPICS IN GEOGRAPHY DISSERTATION Presented In tartlal Fulfi I Intent of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Phllosphy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University BY Francis Eldon Bloomer, A.B., M.Ed. The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have Indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer has accrued both an Intellectual debt and a debt of gratitude to many people while at The Ohio State University. A debt which can never be fully repaid. The writer Is especially grateful to Professor S. Earl Brown whose kindness and encouragement were of inesttmatlble value. Special thanks are due to Professor Paul Klohr, the most knowledgable and humble of men, who was never to busy to help and also to Professor M. Eugene G. 611 Horn for his aid and suggestions. To my major advisor, Professor Robert E. Jewett whose bottom less reservlor of patience and understanding helped bring this disser tation to fruitatIon, the writer will be forever indebted. To my wife DeanIe and to my sons Jeffrey and Scott who suffered in silence during my more trying of times, thanks for understanding. Finally, to Albert Ogren and Joseph Clrrinclone Is extended gratitude for their unwavering friendship. ii VITA February 14, 1925............. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 14, 2005 No. 44 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, rights of individual Senators who feel called to order by the Honorable JOHN PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, they absolutely must address specific E. SUNUNU, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, April 14, 2005. issues, but I continue to encourage New Hampshire. To the Senate: those who want to address immigration Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby in a comprehensive way to do so at a PRAYER appoint the Honorable JOHN E. SUNUNU, a more appropriate time. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of New Hampshire, I know we can work out a process to fered the following prayer: to perform the duties of the Chair. keep moving forward on the emergency Let us pray. TED STEVENS, supplemental bill, but we have to ad- O God, who can test our thoughts and President pro tempore. dress specifically the range of immi- examine our hearts, look within our Mr. SUNUNU thereupon assumed the gration issues that have been brought leaders today and remove anything Chair as Acting President pro tempore. forth to the managers. The managers will continue to con- that will hinder Your Providence. Re- f sider the amendments that are brought place destructive criticism with kind- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY forward. -

PDF Download Eco-Service Development 1St Edition Ebook Free

ECO-SERVICE DEVELOPMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Siegfried Behrendt | 9781351282154 | | | | | Eco-service Development 1st edition PDF Book PSS may foster socioethical benefits? The New York Times. Environment and Planning A. Agroecology Anthrozoology Behavioral geography Community studies Demography Design ecological environmental Ecological humanities Economics energy thermo Environmental education ethics law science studies Ethnobiology botany ecology zoology Forestry Industrial ecology Integrated geography Permaculture Rural sociology Science, technology and society science studies Sustainability science studies Systems ecology Urban ecology geography metabolism studies. A signed book may command a somewhat higher price ; how much, if any, will depend upon whether or not the signature is in demand. Reviews 0. See also: Planetary boundaries and Triple bottom line. Otherwise, please bear all the consequences by yourself. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. Kahle, Eda Gurel-Atay, Eds Informed by extensive research on how people read, think, and learn, Revel is an interactive learning environment that enables students to read, practice, and study in one continuous experience — for less than the cost of a traditional textbook. It has been argued that since the s, the concept of sustainable development has changed from "conservation management" to "economic development", whereby the original meaning of the concept has been stretched somewhat. Whereas, it can be assumed that most corporate impacts on the environment are negative apart from rare exceptions such as the planting of trees this is not true for social impacts. PSS eco-efficient? Download chapter PDF. Unfortunately, this item is not available in your country. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. August As a teen enters puberty, his or her body begins to change in preparation for possible parenthood.