Why Not Here? Teaching Geography to a New Standard. INSTITUTION National Council for Geographic Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Road Map for 21St Century Geography Education Assessment

Editors Daniel C. Edelson A ROAD MAP Richard J. Shavelson Jill A. Wertheim FOR 21st CENTURY GEOGRAPHY EDUCATION Assessment Recommendations and Guidelines for Assessment in Geography Education A Report from the Assessment Committee of the Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project Assessment Recommendations and Guidelines for Assessment in Geography Education Editors Daniel C. Edelson, Richard J. Shavelson, Jill A. Wertheim National Geographic Society Washington, DC A Report from the Assessment Committee of the Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project 2 of 75 This report was created by the Road Map for 21st Century The National Geographic Society is one of the world’s largest nonprofit scientific and Geography Education Project. educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to “increase and diffuse geographic knowledge,” the Society’s mission is to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 400 Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; Daniel C. Edelson, Principal Investigator films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; live events; school publishing programs; interactive Virginia M. Pitts, Project Director media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 10,000 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting The Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project is a collaboration between the geographic literacy. National Geographic Society, the Association of American Geographers, the National Council for Geographic Education, and the American Geographical Society. The views expressed in the report The Association of American Geographers (AAG) is a nonprofit scientific, research, and are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations. -

Touring Exhibitions Programme 2020 – 22

touring exhibitions programme 2020 – 22 designmuseum.org Design Museum Touring Programme Contents The programme was set up in 2002 with the aim of bringing Exhibitions design exhibitions to audiences around the UK and internationally. 4 Material Tales Since then, the museum has organised more than 130 tours to 6 Sneakers Unboxed 104 venues in 31 countries worldwide. 8 Waste Age 10 Football The Design Museum’s touring exhibitions range in size from 12 Got to Keep On 150 to 1000 square metres and encompass all areas of design – 14 Moving to Mars architecture, fashion, graphics, product, digital and more. 16 Breathing Colour by Hella Jongerius 18 Exhibition Catalogues About the Design Museum 24 Terms and Conditions 25 Contacts The Design Museum is the world’s leading museum devoted to architecture and design. Its work encompasses all elements of design, including fashion, product and graphic design. Since it opened its doors in 1989, the museum has displayed everything from an AK-47 to high heels designed by Christian Louboutin. It has staged over 100 exhibitions, welcomed over five million visitors and showcased the work of some of the world’s most celebrated designers and architects including Paul Smith, Zaha Hadid, Jonathan Ive, Miuccia Prada, Frank Gehry, Eileen Gray and Dieter Rams. On 24 November 2016, the Design Museum relocated to Kensington, West London. Architect John Pawson converted the interior of a 1960s modernist building to create a new home for the Design Museum, giving it three times more space in which to show a wider range of exhibitions and significantly extend its learning programme. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

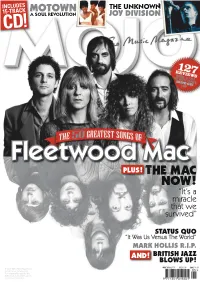

Mojoearlier Results Are Tremendous

INCLUDES MOTOWN THE UNKNOWN 15-TRACK A SOUL REVOLUTION JOY DIVISION CD! Y PLUS! HE MAC NOW! “It’s a miracle that we survived” STATUS QUO MARK HOLLIS R.I.P. AND! BRITISH JAZZ BLOWS UP! MAY 2019 £5.75 US$11.99 CAN$14.99 If your CD is missing please inform your newsagent. For copyright reasons the CD is not available in some overseas territories. Lias Saoudi, torch-carrying FILTER ALBUMS provocateur. These New hypnosis rule, though, remains town (the New York strut of duet of self-destruction. After to be seen. Enlightening 2017’s City Music). With Oh My all of it, JPW is left at the sink, Puritans nevertheless. God, Morby launches a more repeating, “Your love’s the ★★ Charles Waring overtly spiritual quest, hurting kind,” unable or investigating the tensions unwilling to give it up. Inside The Rose between the sacred and Chris Nelson INFECTIOUS MUSIC. CD/DL/LP profane – or “horns on my Underwhelming fourth Our Native head, wings from my album from Southend Daughters shoulder,” as he puts it on The Cranberries erstwhile avant-garde ★★★★ O Behold. A blast of Mary world-beaters Lattimore’s harp on Piss River #### SongsOfOur or Savannah’s glassy Dirty Slimmed down In The End Native Daughters Projectors-style choir hint at to the core the celestial, but if Morby BMG. CD/DL/LP fraternal duo SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS. CD/DL Edwyn Collins speaks in tongues, they are still Final album, with Step of Jack and New history from onet very much those of Bob Dylan #### Street back producing George Barnett leader of the Carolina and Leonard Cohen – earthly, after the 2016 Chocolate Drops. -

Album of the Year Record of the Year

Album of the Year I, I Bon Iver NORMAN F—ING ROCKWELL! Lana del Rey WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO? Billie Eilish THANK U, NEXT Ariana Grande I USED TO KNOW HER H.E.R. 7 Lil Nas X CUZ I LOVE YOU Lizzo FATHER OF THE BRIDE Vampire Weekend Record of the Year HEY MA Bon Iver BAD GUY Billie Eilish 7 RINGS Ariana Grande HARD PLACE H.E.R. TALK Khalid OLD TOWN ROAD Lil Nas X ft. Billy Ray Cyrus TRUTH HURTS Lizzo SUNFLOWER Post Malone Song of the Year ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY Natalie Hemby, Lady Gaga, Hillary Lindsey and Lori McKenna, songwriters (Lady Gaga) BAD GUY Billie Eilish O’Connell & Finneas O’Connell, songwriters (Billie Eilish) BRING MY FLOWERS NOW Brandi Carlile, Phil Hanseroth, Tim Hanseroth and Tanya Tucker, songwriters (Tanya Tucker) HARD PLACE Ruby Amanfu, Sam Ashworth, D. Arcelious Harris, H.E.R. & Rodney Jerkins, songwriters (H.E.R.) LOVER Taylor Swift NORMAN F***ING ROCKWELL Jack Antonoff and Lana del Ray, songwriters (Lana del Rey) SOMEONE YOU LOVED Tom Barnes, Lewis Capaldi, Pete Kelleher, Benjamin Kohn and Sam Roman, songwriters (Lewis Capaldi) TRUTH HURTS Steven Cheung, Eric Frederic, Melissa Jefferson and Jesse Saint John, songwriters (Lizzo) Best New Artist BLACK PUMAS BILLIE EILISH LIL NAS X LIZZO MAGGIE ROGERS ROSALíA TANK AND THE BANGAS YOLA Best Pop Solo Performance SPIRIT Beyoncé BAD GUY Billie Eilish 7 RINGS Ariana Grande TRUTH HURTS Lizzo YOU NEED TO CALM DOWN Taylor Swift Best Pop Duo/Group Performance BOYFRIEND Ariana Grande & Social House SUCKER Jonas Brothers OLD TOWN ROAD Lil Nas X Featuring Billy -

Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Edited by Peter Ludlow

Ludlow cover 7/7/01 2:08 PM Page 1 Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias Crypto Anarchy, Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias edited by Peter Ludlow In Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, Peter Ludlow extends the approach he used so successfully in High Noon on the Electronic Frontier, offering a collection of writings that reflect the eclectic nature of the online world, as well as its tremendous energy and creativity. This time the subject is the emergence of governance structures within online communities and the visions of political sovereignty shaping some of those communities. Ludlow views virtual communities as laboratories for conducting experiments in the Peter Ludlow construction of new societies and governance structures. While many online experiments will fail, Ludlow argues that given the synergy of the online world, new and superior governance structures may emerge. Indeed, utopian visions are not out of place, provided that we understand the new utopias to edited by be fleeting localized “islands in the Net” and not permanent institutions. The book is organized in five sections. The first section considers the sovereignty of the Internet. The second section asks how widespread access to resources such as Pretty Good Privacy and anonymous remailers allows the possibility of “Crypto Anarchy”—essentially carving out space for activities that lie outside the purview of nation-states and other traditional powers. The Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, third section shows how the growth of e-commerce is raising questions of legal jurisdiction and taxation for which the geographic boundaries of nation- states are obsolete. The fourth section looks at specific experimental governance and Pirate Utopias structures evolved by online communities. -

University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor. Michigan

72-4425 BLOOMER, Francis Eldon, 1925- SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHERS* PERCEPTION OF TOPICS IN GEOGRAPHY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, general U n iv e rs ity M ic ro film s . A XEROXCompany , Ann Arbor. Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHERS' PERCEPTION OF TOPICS IN GEOGRAPHY DISSERTATION Presented In tartlal Fulfi I Intent of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Phllosphy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University BY Francis Eldon Bloomer, A.B., M.Ed. The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have Indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer has accrued both an Intellectual debt and a debt of gratitude to many people while at The Ohio State University. A debt which can never be fully repaid. The writer Is especially grateful to Professor S. Earl Brown whose kindness and encouragement were of inesttmatlble value. Special thanks are due to Professor Paul Klohr, the most knowledgable and humble of men, who was never to busy to help and also to Professor M. Eugene G. 611 Horn for his aid and suggestions. To my major advisor, Professor Robert E. Jewett whose bottom less reservlor of patience and understanding helped bring this disser tation to fruitatIon, the writer will be forever indebted. To my wife DeanIe and to my sons Jeffrey and Scott who suffered in silence during my more trying of times, thanks for understanding. Finally, to Albert Ogren and Joseph Clrrinclone Is extended gratitude for their unwavering friendship. ii VITA February 14, 1925............. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 14, 2005 No. 44 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, rights of individual Senators who feel called to order by the Honorable JOHN PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, they absolutely must address specific E. SUNUNU, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, April 14, 2005. issues, but I continue to encourage New Hampshire. To the Senate: those who want to address immigration Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby in a comprehensive way to do so at a PRAYER appoint the Honorable JOHN E. SUNUNU, a more appropriate time. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of New Hampshire, I know we can work out a process to fered the following prayer: to perform the duties of the Chair. keep moving forward on the emergency Let us pray. TED STEVENS, supplemental bill, but we have to ad- O God, who can test our thoughts and President pro tempore. dress specifically the range of immi- examine our hearts, look within our Mr. SUNUNU thereupon assumed the gration issues that have been brought leaders today and remove anything Chair as Acting President pro tempore. forth to the managers. The managers will continue to con- that will hinder Your Providence. Re- f sider the amendments that are brought place destructive criticism with kind- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY forward. -

Ed 132 647 Title Institution Report No Pub Date

DOCUMERT RESUME ED 132 647 EA 008 921 TITLE Principles and Standards for Accrediting Elementary and Secondary Schools: and List of Approved Courses--Grades 7-12. Revised. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. REPORT NO TEA-Bull-560 PUB DATE Oct 74 NOTE 85p.; Not available in hard copy due to small print size of original AVAILABLE FROM Texas Education Agency, 201 East 11th Street, Austin, Texas 78701 ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDES. DESCRIPTORS *Accreditation (Institutions); Courses; Educational Legislation; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; *State Boards of Education; State Curriculum Guides; State Departments of Education; *State Legislation; *State Standards IDENTIFIERS *Texas ABSTRACT This booklet presents _fficial school accreditation principles and standards for elementary and secondary schools and lists of approved courses for grades 7-12, as revised by the Texas State Board of Education in October 1974. The booklet is organized in four sections that present principles and standards for elementary and secondary schools, procedures for accreditation of elementary and secondary schools, lists of approved courses for grades 7-12, and selectetliegal provisions from the Texas. Education Code. Most of the booklet is devoted to the revised accreditation principles and standards. A total of 11 general principles are presented, each followed by a number of more specific standards. (JG) * Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

In This Iss Lectures, Videos and Address

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 2-8-1988 University News, February 8 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. 'fllelJniversityNews Volume VIIJ, Issue 17 ' , Boise State University February 8, 1988 Purchase of campus school may offer space by Mack Sermon location," Wecker said, adding that The, University News "We feel we've been able to compen- sate and provide a quality BSU may solve crowding problems playground." In order to build the for itself and Campus Elementary dishes where they are, the university School by purchasing the school, if made use of space that formerly had, the legislature provides the funding, been used as part of the playground. according to John Franden, executive Wecker said the heavy, traffic assistant to the BSU president. around the school and the lack of The school has been warned two parking were more direct problems years in a row that its playground is resulting from the lack, of space. too small and that next yearIt may "Some parents won't even attend face sanctions, according to Principal 'our parent-teacher conferences Robert, Wecker. because they can't find a parking However, Franden said, "If we can space," Weckcr said.