Landforms of the Louisiana Coastal Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great's Tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, Eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geomorphology 100 (2008) 377–400 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N. Marriner a, , J.P. Goiran b, C. Morhange a a CNRS CEREGE UMR 6635, Université Aix-Marseille, Europôle de l'Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 04, France b CNRS MOM Archéorient UMR 5133, 5/7 rue Raulin, 69365 Lyon cedex 07, France Received 25 July 2007; received in revised form 10 January 2008; accepted 11 January 2008 Available online 2 February 2008 Abstract Tyre and Alexandria's coastlines are today characterised by wave-dominated tombolos, peculiar sand isthmuses that link former islands to the adjacent continent. Paradoxically, despite a long history of inquiry into spit and barrier formation, understanding of the dynamics and sedimentary history of tombolos over the Holocene timescale is poor. At Tyre and Alexandria we demonstrate that these rare coastal features are the heritage of a long history of natural morphodynamic forcing and human impacts. In 332 BC, following a protracted seven-month siege of the city, Alexander the Great's engineers cleverly exploited a shallow sublittoral sand bank to seize the island fortress; Tyre's causeway served as a prototype for Alexandria's Heptastadium built a few months later. We report stratigraphic and geomorphological data from the two sand spits, proposing a chronostratigraphic model of tombolo evolution. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tombolo; Spit; Tyre; Alexandria; Mediterranean; Holocene 1. Introduction Courtaud, 2000; Browder and McNinch, 2006); (2) establishing a typology of shoreline salients and tombolos (Zenkovich, 1967; The term tombolo is used to define a spit of sand or shingle Sanderson and Eliot, 1996); and (3) modelling the geometrical linking an island to the adjacent coast. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Missouri River Floodplain from River Mile (RM) 670 South of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St

Hydrogeomorphic Evaluation of Ecosystem Restoration Options For The Missouri River Floodplain From River Mile (RM) 670 South of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St. Louis, Missouri Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 Minneapolis, Minnesota Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 15-02 Mickey E. Heitmeyer Joseph L. Bartletti Josh D. Eash December 2015 HYDROGEOMORPHIC EVALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION OPTIONS FOR THE MISSOURI RIVER FLOODPLAIN FROM RIVER MILE (RM) 670 SOUTH OF DECATUR, NEBRASKA TO RM 0 AT ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 Refuges and Wildlife Minneapolis, Minnesota By: Mickey E. Heitmeyer Greenbrier Wetland Services Advance, MO 63730 Joseph L. Bartletti Prairie Engineers of Illinois, P.C. Springfield, IL 62703 And Josh D. Eash U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3 Water Resources Branch Bloomington, MN 55437 Greenbrier Wetland Services Report No. 15-02 December 2015 Mickey E. Heitmeyer, PhD Greenbrier Wetland Services Route 2, Box 2735 Advance, MO 63730 www.GreenbrierWetland.com Publication No. 15-02 Suggested citation: Heitmeyer, M. E., J. L. Bartletti, and J. D. Eash. 2015. Hydrogeomorphic evaluation of ecosystem restoration options for the Missouri River Flood- plain from River Mile (RM) 670 south of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St. Louis, Missouri. Prepared for U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3, Min- neapolis, MN. Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 15-02, Blue Heron Conservation Design and Print- ing LLC, Bloomfield, MO. Photo credits: USACE; http://statehistoricalsocietyofmissouri.org/; Karen Kyle; USFWS http://digitalmedia.fws.gov/cdm/; Cary Aloia This publication printed on recycled paper by ii Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... -

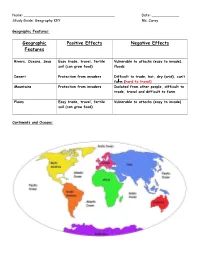

Geographic Features Positive Effects Negative Effects

Name: ________________________________________ Date: ____________ Study Guide: Geography KEY Ms. Carey Geographic Features: Geographic Positive Effects Negative Effects Features Rivers, Oceans, Seas Easy trade, travel, fertile Vulnerable to attacks (easy to invade), soil (can grow food) floods Desert Protection from invaders Difficult to trade, hot, dry (arid), can’t farm (hard to travel) Mountains Protection from invaders Isolated from other people, difficult to trade, travel and difficult to farm Plains Easy trade, travel, fertile Vulnerable to attacks (easy to invade) soil (can grow food) Continents and Oceans: Vocabulary: River Archipelago Ocean Island Continent Pangaea Desert Plains Peninsula Mountain 1. Island: An area of land completely surrounded by water. 2. Peninsula: An area of land completely surrounded by water on three (3) sides and connected to the mainland by an isthmus. 3. Archipelago: A chain of islands, such as Japan and Greece. 4. Continent: A large body of LAND. (hint: there are seven) 5. Ocean: A large body of salt water. (hint: there are four main ones) 6. Desert: A large, arid (dry) area of land which receives less than 10 inches of rain annually. 7. River: A freshwater body of water which flows from a higher elevation to a lower one. 8. Mountain: An area that rises steeply at least 2,000 feet above sea level; usually wide at the bottom and rising to a narrow peak or ridge. 9. Plains: A large area of flat or gently rolling land which is fertile and good for farming. 10. Pangaea: The name of a huge super continent that scientists believe split apart about 200 million years ago, forming different continents. -

Geomorphometric Delineation of Floodplains and Terraces From

Earth Surf. Dynam., 5, 369–385, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-5-369-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Geomorphometric delineation of floodplains and terraces from objectively defined topographic thresholds Fiona J. Clubb1, Simon M. Mudd1, David T. Milodowski2, Declan A. Valters3, Louise J. Slater4, Martin D. Hurst5, and Ajay B. Limaye6 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Drummond Street, Edinburgh, EH8 9XP, UK 2School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Crew Building, King’s Buildings, Edinburgh, EH9 3JN, UK 3School of Earth, Atmospheric, and Environmental Science, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK 4Department of Geography, Loughborough University, Loughborough, LE11 3TU, UK 5School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, UK 6Department of Earth Sciences and St. Anthony Falls Laboratory, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA Correspondence to: Fiona J. Clubb ([email protected]) Received: 31 March 2017 – Discussion started: 12 April 2017 Revised: 26 May 2017 – Accepted: 9 June 2017 – Published: 10 July 2017 Abstract. Floodplain and terrace features can provide information about current and past fluvial processes, including channel response to varying discharge and sediment flux, sediment storage, and the climatic or tectonic history of a catchment. Previous methods of identifying floodplain and terraces from digital elevation models (DEMs) tend to be semi-automated, requiring the input of independent datasets or manual editing by the user. In this study we present a new method of identifying floodplain and terrace features based on two thresholds: local gradient, and elevation compared to the nearest channel. -

Tectonic Control on 10Be-Derived Erosion Rates in the Garhwal Himalaya, India Dirk Scherler,1,2 Bodo Bookhagen,3 and Manfred R

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH: EARTH SURFACE, VOL. 119, 1–23, doi:10.1002/2013JF002955, 2014 Tectonic control on 10Be-derived erosion rates in the Garhwal Himalaya, India Dirk Scherler,1,2 Bodo Bookhagen,3 and Manfred R. Strecker 1 Received 28 August 2013; revised 13 November 2013; accepted 26 November 2013. [1] Erosion in the Himalaya is responsible for one of the greatest mass redistributions on Earth and has fueled models of feedback loops between climate and tectonics. Although the general trends of erosion across the Himalaya are reasonably well known, the relative importance of factors controlling erosion is less well constrained. Here we present 25 10Be-derived catchment-averaged erosion rates from the Yamuna catchment in the Garhwal Himalaya, 1 northern India. Tributary erosion rates range between ~0.1 and 0.5 mm yrÀ in the Lesser 1 Himalaya and ~1 and 2 mm yrÀ in the High Himalaya, despite uniform hillslope angles. The erosion-rate data correlate with catchment-averaged values of 5 km radius relief, channel steepness indices, and specific stream power but to varying degrees of nonlinearity. Similar nonlinear relationships and coefficients of determination suggest that topographic steepness is the major control on the spatial variability of erosion and that twofold to threefold differences in annual runoff are of minor importance in this area. Instead, the spatial distribution of erosion in the study area is consistent with a tectonic model in which the rock uplift pattern is largely controlled by the shortening rate and the geometry of the Main Himalayan Thrust fault (MHT). Our data support a shallow dip of the MHT underneath the Lesser Himalaya, followed by a midcrustal ramp underneath the High Himalaya, as indicated by geophysical data. -

Chapter 5 Groundwater Quality and Hydrodynamics of an Acid Sulfate Soil Backswamp

Chapter 5 Groundwater Quality and Hydrodynamics of an Acid Sulfate Soil Backswamp 5.1 Introduction Intensive drainage of coastal floodplains has been the main factor contributing to the oxidation of acid sulfate soils (ASS) (Indraratna, Blunden & Nethery 1999; Sammut, White & Melville 1996). Drainage of backswamps removes surface water, thereby increasing the effect of evapotranspiration on watertable drawdown (Blunden & Indraratna 2000) and transportation of acidic salts to the soil surface through capillary action (Lin, Melville & Hafer 1995; Rosicky et al. 2006). During high rainfall events the oxidation products (i.e. metals and acid) are mobilised into the groundwater, and acid salts at the sediment surface are dissolved directly into the surface water (Green et al. 2006). The high efficiency of drains readily transports the acidic groundwater and surface water into the estuary and can have a detrimental impact on downstream habitats (Cook et al. 2000). The quality of water discharged from a degraded ASS wetland is controlled by the water balance, which over a given time period is: P + I + Li = E + Lo + D + S (Equation 5.1) where P is precipitation, I is irrigation, Li is the lateral inflow of water, E is evapotranspiration, Lo is surface and subsurface lateral outflow of water, D is the drainage to the watertable and S is the change in soil moisture storage above the watertable (Indraratna, Tularam & Blunden 2001; Sammut, White & Melville 1996; White et al. 1997). While this equation may give a general overview of sulfidic floodplain hydrology, an understanding of site-specific details is required for effective remediation and management of degraded ASS wetlands. -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

Southeastern Coastal Plains-Caribbean Region Report

Southeastern Coastal Plains-Caribbean Region Report U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan April 10, 2000 (Revised September 30, 2002) Written by: William C. (Chuck) Hunter U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1875 Century Boulevard Atlanta, Georgia 30345 404/679-7130 (FAX 7285) [email protected] along with Jaime Collazo, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC Bob Noffsinger, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Manteo, NC Brad Winn, Georgia DNR Wildlife Resources Division, Brunswick, GA David Allen, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, Trenton, NC Brian Harrington, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, Manomet, MA Marc Epstein, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Merritt Island NWR, FL Jorge Saliva, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Boqueron, PR Executive Summary This report articulates what is needed in the Southeastern Coastal Plains and Caribbean Region to advance shorebird conservation. A separate Caribbean Shorebird Plan is under development and will be based in part on principles outlined in this plan. We identify priority species, outline potential and present threats to shorebirds and their habitats, report gaps in knowledge relevant to shorebird conservation, and make recommendations for addressing identified problems. This document should serve as a template for a regional strategic management plan, with step-down objectives, local allocations and priority needs outlined. The Southeastern Coastal Plains and Caribbean region is important for breeding shorebirds as well as for supporting transient species during both northbound -

The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 8-8-2007 The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands Lon Boudreaux Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Boudreaux, Lon Jr., "The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 564. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/564 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies By Lon J. Boudreaux Jr. B.S. Our Lady of Holy Cross College, 1992 M.S. University of New Orleans, 2007 August, 2007 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................. -

5Site Assessment

Site Assessment 55.1 Collecting Site Data 5.2 Analyzing and Interpreting Site Data 5.3 Project Site Risk Assessment 5.4 Document Key Design Considerations and Recommendations 5.5 Reference Reach: The Pattern for Stream- Simulation Design Stream Simulation Steps and Considerations in Site Assessment Sketch a planview map Topographic survey l Site and road topography. l Channel longitudinal profile. l Channel and flood-plain cross sections. Measure size and observe arrangement of bed materials l Pebble count or bulk sample. l Bed mobility and armoring. l Bed structure type and stability (steps, bars, key features). Describe bank characteristics and stability Conduct preliminary geotechnical investigation l Bedrock. l Soils. l Engineering properties. l Mass wasting. l Ground water. Analyze and interpret site data l Bed material size and mobility. l Cross section analysis. Flood-plain conveyance. Bank stability. Lateral adjustment potential. l Longitudinal profile analysis. Vertical adjustment potential. l General channel stability. Document key design considerations and recommendations. RESULTS Geomorphic characterization of reach. Engineering site plan map for design. Understanding of site risk factors and potential channel changes over structure lifetime. Detailed project objectives, including extent and objectives of any channel restoration. Design template for simulated streambed (reference reach). Figure 5.1—Steps and considerations in site assessment. Chapter 5—Site Assessment After verifying that the site is suitable for a crossing and will probably be suitable for stream simulation, the next step is to conduct a thorough site assessment. In this phase, you will collect the topographic and other data necessary for designing both the stream-simulation channel and the crossing structure and road approaches. -

Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Report

Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Report ## by Legend Paul R. Knox, P.G. State Line Shelf Edge Yegua-Jackson outcrop Van A. Kelley, P.G. County Boundaries Well Locations Astrid Vreugdenhil Sediment Input Axis (Size Relative to Sed. Vol.) Facies Neil Deeds, P.E. Deltaic/Delta Front/Strandplain Wave-Dominated Delta Steven Seni, Ph.D., P.G. Delta Margin < 100' Fluvial Floodplain Slope 020406010 Miles Shelf-Edge Delta Shelf/Slope Sand > 100' Texas Water Development Board P.O. Box 13231, Capitol Station Austin, Texas 7871-3231 September 2007 TWDB Report ##: Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Texas Water Development Board Report ## Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain by Van A. Kelley, P.G. Astrid Vreugdenhil Neil Deeds, P.E. INTERA Incorporated Paul R. Knox, P.G. Baer Engineering and Environmental Consulting, Incorporated Steven Seni, Ph.D., P.G. Consulting Geologist September 2007 This page is intentionally blank. ii This page is intentionally blank. iv TWDB Report ##: Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................................E-i 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1-1 2. Study Area and Geologic Setting.......................................................................................