Southeastern Coastal Plains-Caribbean Region Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44)

W&M ScholarWorks CCB Technical Reports Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) 1999 Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44) B. D. Watts The Center for Conservation Biology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccb_reports Recommended Citation Watts, B. D., "Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44)" (1999). CCB Technical Reports. 454. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccb_reports/454 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CCB Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44) April 1999 Center for Conservation Biology College of William and Mary & Virginia Commonwealth University Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44) April 1999 Bryan D. Watts, PhD Center for Conservation Biology College of William and Mary & Virginia Commonwealth University Address comments to: Bryan D. Watts Center for Conservation Biology College of William and Mary Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 (757) 221-2247 [email protected] Recommended Citation: Watts, B. D. 1999. Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44). Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-99-08. College of William and Mary & Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA. 84 pp. The Center for Conservation Biology is an organization dedicated to discovering innovative solutions to environmental problems that are both scientifically sound and practical within today’s social context. -

Structural and Stratigraphic Framework, and Spatial Distribution of Permeability of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, North Carolina to New York

Structural and Stratigraphic Framework, and Spatial Distribution of Permeability of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, North Carolina to New York GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 796 Structural and Stratigraphic Framework, and Spatial Distribution of Permeability of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, North Carolina to New York By PHILIP M. BROWN, JAMES A. MILLER, and FREDERICK M. SWAIN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 796 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600285 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 2401-00243 CONTENTS Page Abstract.___________________________________________ 1 Stratigraphic framework Continued Introduction. __ _____________________---____----_-____ 2 Lithostratigraphic description and biostratigraphic Location of area.____________________________________ 3 discussion Continued Acknowledgments. __________________________________ 3 Cenozoic Era__ ____________-_-___--__-------_ 45 Previous work_______________________________________ 5 Tertiary System. _______.-_______----__-_ 45 Purpose of this report. ________________________________ 6 Paleocene Series _ ___________________ 45 Structural architecture._______________________________ 6 Midway Stage Rocks of Midway Introduction, __ ________________________________ 6 Age_ ___----__-____--_------__ 45 General discussion________________________ -

Delaware Pennsylvania

Comparing and Contrasting Delaware and Pennsylvania Name: _________________________ Delaware Delaware, one of America’s original 13 colonies, became America’s first state on December 7, 1787. Hence, its nickname is simply the First State. It became the first state when it ratified, or accepted, the United States Constitution. Delaware is located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, entirely within the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Its capital is Dover and its largest city is Wilmington. Delaware’s land is mostly flat. Its east coast has many wetlands and popular beaches. Delaware is the second smallest state in America in terms of area, and fifth smallest in terms of population. There are less than a million people who live in Delaware. It borders three states: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Delaware and New Jersey are separated by the wide Delaware River. Pennsylvania Pennsylvania, one of the original 13 colonies, became America’s second state on December 12, 1787. At the time, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was the capital of the United States. Millions of people flock to Philadelphia every year to see Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. Independence Hall was the site of the drafting of both the Declaration of independence and the United States Constitution, two of the most important documents in American history. Gettysburg National Park, located in southern Pennsylvania, was the site of the largest battle ever fought on American soil. The majority of Pennsylvania is covered by the Appalachian Mountains and foothills. Pennsylvania is the only state in the Mid-Atlantic region without beaches. It borders five states: New York, New Jersey, Maryland, West Virginia, and Ohio. -

The Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 44)

Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 44) Partners in Flight: Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Bird Conservation Plan (Physiographic Area #44) VERSION 1.0 April 1999 Address comments to: Bryan D. Watts Center for Conservation Biology College of William and Mary Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 (757) 221-2247 [email protected] *********************************************** Front cover illustration from ‘All the Birds of North America’ by Jack Griggs, courtesy of HarperCollins publishers. PIF Bird Conservation Plan -- Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This draft plan was produced with funds provided by the Northern Neck Audubon Society, the Tennessee Conservation League, and the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary. I thank Bob Ford and Ken Rosenberg for guidance throughout the planning process. Dana Bradshaw, Mike Wilson, and Marian Watts provided assistance with information and literature. PIF Bird Conservation Plan -- Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain 3 MID-ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN BIRD CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain was the site of the first successful European settlement in North America and its landscape has been subject to influence by European culture for nearly four centuries. Currently, the urban crescent from Baltimore south to Richmond and east to Norfolk is experiencing one of the fastest human growth rates in North America. Managing this population growth while maintaining functional natural ecosystems is the greatest conservation challenge faced by land managers within the region. Despite these important management challenges, the potential for successful conservation of priority bird populations remains optimistic. This optimism stems from 1) the fact that a large number of lands critical to priority bird populations are currently protected or held by PIF partners, and 2) many priority species remain relatively abundant and widespread within the region. -

Geologic Framework and Petroleum Potential of the Atlantic Coastal Plain and Continental Shelf

GEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK AND PETROLEUM POTENTIAL OF THE ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN AND CONTINENTAL SHELF ^^^*mmm ^iTlfi".^- -"^ -|"CtS. V is-^K-i- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 659 cV^i-i'^S^;-^, - >->"!*- -' *-'-__ ' ""^W^T^^'^rSV-t^^feijS GEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK AND PETROLEUM POTENTLY L OF THE ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN AND CONTINENTAL SHELF By JOHN C. MAHBR ABSTRACT less alined with a string of seamounts extending down the continental rise to the abyssal plain. The trends parallel to The Atlantic Coastal Plain and Continental Shelf of North the Appalachians terminate in Florida against a southeasterly America is represented by a belt of Mesozoic and Cenozoic magnetic trend thought by some to represent an extension of rocks, 150 'to 285 miles wide and 2,400 miles long, extending the Ouachita Mountain System. One large anomaly, known as from southern Florida to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. the slope anomaly, parallels the edge of the .continental shelf This belt of Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks encompasses an area north of Cape Fear and seemingly represents th** basement of about 400,000 to 450,000 square miles, more than three- ridge located previously by seismic methods. fourths of which is covered by the Atlantic Ocean. The volume Structural contours on the basement rocks, as drawn from of Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks beneath the Atlantic Coastal outcrops, wells, and seismic data, parallel the Appalachian Plain and Continental Shelf exceeds 450,000 cubic miles, per Mountains except in North and South Carolina, where they haps by a considerable amount. More than one-half of this is bulge seaward around the Cape Fear arch, and in Florida, far enough seaward to contain marine source rocks in sufficient where the deeper contours follow the peninsula. -

Federal Register/Vol. 72, No. 27/Friday, February 9, 2007/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 72, No. 27 / Friday, February 9, 2007 / Rules and Regulations 6165 all provisions in §§ 1.181–1T through SUMMARY: This Treasury decision purchase. Establishment of a viticultural 1.181–5T to the productions. establishes the Outer Coastal Plain area is neither an approval nor an (c) Special rules for returns filed for viticultural area in southeastern New endorsement by TTB of the wine prior taxable years. If before March 12, Jersey. The viticultural area consists of produced in that area. 2007, an owner of a film or television approximately 2,255,400 acres and Requirements production began principal photography includes all of Cumberland, Cape May, (or ‘‘in-between’’ animation) for the Atlantic, and Ocean Counties and Section 4.25(e)(2) of the TTB production after October 22, 2004, and portions of Salem, Gloucester, Camden, regulations outlines the procedure for filed its original Federal income tax Burlington, and Monmouth Counties. proposing an American viticultural area return for the year such costs were first We designate viticultural areas to allow and provides that any interested party paid or incurred without making an bottlers to better describe the origin of may petition TTB to establish a grape- election under section 181 for the costs their wines and to allow consumers to growing region as a viticultural area. of the production, and if the taxpayer better identify the wines they may Section 9.3(b) of the TTB regulations wants to make an election under section purchase. requires the petition to include— • 181 for such taxable year, see § 1.181– DATES: Effective Date: March 12, 2007. -

Mid-Atlantic Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment and Synthesis: a Report from the Mid-Atlantic Climate Change Response Framework Project

United States Department of Agriculture Mid-Atlantic Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment and Synthesis: A Report from the Mid-Atlantic Climate Change Response Framework Project Forest Northern General Technical Service Research Station Report NRS-181 October 2018 ABSTRACT Forest ecosystems will be affected directly and indirectly by a changing climate over the 21st century. This assessment evaluates the vulnerability of 11 forest ecosystems in the Mid-Atlantic region (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, eastern Maryland, and southern New York) under a range of future climates. We synthesized and summarized information on the contemporary landscape, provided information on past climate trends, and described a range of projected future climates. This information was used to parameterize and run multiple forest impact models, which provided a range of potential tree responses to climate. Finally, we brought these results before two multidisciplinary panels of scientists and land managers familiar with the forests of this region to assess ecosystem vulnerability through a formal consensus-based expert elicitation process. Each chapter of this assessment builds on the previous chapter. The description of the contemporary landscape presents major forest trends and stressors currently threatening forests in the Mid-Atlantic region and defines the forest communities being assessed. The background information in Chapter 2 summarizes climate data analysis and climate models. Analysis of climate records in Chapter 3 indicates that average temperatures and total precipitation in the region have increased. Downscaled climate models in Chapter 4 project potential increases in temperature in every season, but projections for precipitation indicate slight increases in winter and spring, and high variability in summer and fall projections, depending on the scenario. -

New England – Middle Atlantic Region I

New England – Middle Atlantic Region I. States of the New England – Middle Atlantic Region: • Maine - Delaware • New Hampshire - New York • Vermont - New Jersey • Massachusetts - Pennsylvania • Connecticut - Maryland • Rhode Island II. Physical Feature of the New England – Middle Atlantic Region: • The Hudson River - which is located in New York • The Atlantic Ocean – which is on the eastern coast • St. Lawrence River • Great Lakes – ▪ Lake Erie ▪ Lake Huron ▪ Lake Michigan ▪ Lake Superior ▪ Lake Ontario • Appalachian Mountains • Cape Cod • Chesapeake Bay III. Climate of the New England – Middle Atlantic Region • The climate of most of the New England-Middle Atlantic States consist of extreme weather conditions, such as 100+ degrees during the summer, and under freezing temperatures during the winter. • Some southern states in this region had long, hot summers with a long growing season and short winters. IV. Other Features • If you lived in the northern part of this region, you probably made money by becoming a merchant, or a ship builder, or a manufacturer, or a whaler or fisherman. • If you lived in the southern part of the region, you made money by trade or by ship building. • You might raise livestock and staple crops which include: wheat, barley, and oats. • These foods, as well as furs, pickled beef, and beef are important products to this region. These products are vital to the trade process. Southeast Region I. The southeast region consist of the following states: • West Virginia • Virginia • North Carolina • South Carolina • Georgia • Florida • Kentucky • Tennessee • Alabama • Mississippi • Arkansas • Louisiana II. Physical features of the southeast region: • The Atlantic Ocean – on the east coast • The Appalachian Mountains – which run through the eastern states in this region • Ohio River – which runs along West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi • Gulf of Mexico • Gulf Coastal Plain • Atlantic Coastal Plain • Mississippi River III. -

The South Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 03)

Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The South Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 03) Partners in Flight SOUTH ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN PARTNERS IN FLIGHT BIRD CONSERVATION PLAN (Physiographic Area #03) Version 1.0 May 2001 Written by: William C. Hunter, Lori Peoples, and Jaime Collazo William C. Hunter* Lori H. Peoples and Jaime A. Collazo U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service North Carolina Cooperative Research Unit 1875 Century Boulevard, Suite 420 North Carolina State University Atlanta, GA 30345 Raleigh, NC 27695 404/679-7130 (FAX 7285) [email protected] *Send reviews, questions, or comments to this address Front cover illustration from ‘All the Birds of North America’ by Jack Griggs, courtesy of HarperCollins publishers. SOUTH ATLANTIC COASTAL PLAIN BIRD CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The South Atlantic Coastal Plain, one of four coastal plain divisions recognized by Partners in Flight, is an extensive area with a high diversity of habitat types and associated bird species. Although broadly similar to other coastal plain divisions, several key habitat features distinguish the South Atlantic Coastal Plain and provide unique opportunities for conservation measures. The South Atlantic Coastal Plain is home to the largest forested floodplains outside of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and includes unique non-alluvial wetlands such as the Great Dismal Swamp, pocosins, and Carolina bays. In addition, the largest remnants of former longleaf pine ecosystems and the best remaining examples of "natural" barrier and sea islands and maritime forests and woodlands are found in the South Atlantic Coastal Plain. Due to the diversity of habitat within the physiographic area, several habitat- planning units have been utilized in order to aid in conservation and management planning. -

Atlantic Coast and Inner Shelf

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Books and Book Chapters Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2016 Atlantic Coast and Inner Shelf David E. Krantz Carl H. Hobbs III Virginia Institute of Marine Science Geoffrey L. Wikel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Krantz, David E.; Hobbs, Carl H. III; and Wikel, Geoffrey L., "Atlantic Coast and Inner Shelf" (2016). VIMS Books and Book Chapters. 117. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks/117 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATLANTIC COAST AND INNER SHELF David E. Krantz Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606, [email protected] Carl H. Hobbs, III Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William & Mary, Gloucester Point, VA 23062, [email protected] Geoffrey L. Wikel Office of Environmental Programs, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Herndon, VA 20170, [email protected] INTRODUCTION alternating deep channels and shallow shoals between the Virginia Capes–Cape Charles on the southern tip of the Eastern The continental margin of Virginia, and of North America Shore and Cape Henry on the northern edge of Virginia Beach. more broadly, is the physical transition from the high elevation The Virginia coast shares its evolutionary history with of the continent to the low of the ocean basin. -

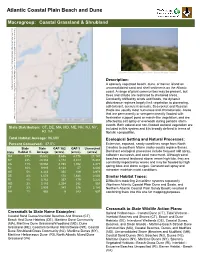

Atlantic Coastal Plain Beach and Dune

Atlantic Coastal Plain Beach and Dune Macrogroup: Coastal Grassland & Shrubland yourStateNatural Heritage Ecologist for more information about this habitat. This is modeledmap a distributiononbased current and is data nota substitute for field inventory. based Contact © Kathleen Strakosch Walz (New Jersey Natural Heritage Program) Description: A sparsely vegetated beach, dune, or barrier island on unconsolidated sand and shell sediments on the Atlantic coast. A range of plant communities may be present, but trees and shrubs are restricted to sheltered areas. Constantly shifted by winds and floods, the dynamic disturbance regimes largely limit vegetation to pioneering, salt-tolerant, succulent annuals. Sea-rocket and Russian thistle are usually most numerous and characteristic. Areas that are permanently or semipermanently flooded with freshwater support pond or marsh-like vegetation, and are affected by salt spray or overwash during periodic storm events. Both upland and non-flooded wetland vegetation are State Distribution: CT, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, included in this system and it is broadly defined in terms of RI, VA floristic composition. Total Habitat Acreage: 96,690 Ecological Setting and Natural Processes: Percent Conserved: 37.5% Extensive, exposed, sandy coastlines range from North State State GAP 1&2 GAP 3 Unsecured Carolina to southern Maine (rocky coasts replace these). State Habitat % Acreage (acres) (acres) (acres) Dominant ecological processes include frequent salt spray, MA 37% 35,602 9,686 4,776 21,140 saltwater overwash, and sand movement. Although sand NY 22% 20,888 2,172 3,313 15,403 beaches extend landward above mean high tide, they are constantly impacted by waves and may be flooded by high VA 11% 10,964 4,785 1,702 4,477 spring tides and storm surges.