University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have You Ever? Oh, When?

Activate: Games for Learning American English Game 9: Have You Ever…? Oh, When? Have You Ever…? Oh, When? gives students practice with common conversational moves by asking and telling about past experiences. The teacher may want to explain the use of the present perfect and the meaning of “ever” in “have you ever.” Instructions 1. Have students (the players) sit in groups of 3–4. 2. Determine who goes first and progress clockwise or counter-clockwise. 3. Each player rolls the dice in turn. 4. On their turns, the players move their game pieces along the path according to the number of spaces indicated by the dice. 5. On the space where they land, the players read the question aloud. 6. The players respond to their question. If the answer is “yes,” players should say the last time they did the activity. If the answer is “no,” players should tell something that they have done that is related. 7. The game continues until one or all players reach the ‘Finish’ space. “Player Talk” in Have You Ever…? Oh, When? Cue “Player Talk” Have you ever No I haven’t, but I have swum in an ocean. (Simple swum in a river? response) Have you ever Yes, I have. The last time was when I visited my aunt. I watched a baseball saw a game on TV. (Complex response) game? 27 Activate: Games for Learning American English Game Squares START: WE’RE SO READY! 1. Have you ever swum in a river? 2. Have you ever watched a baseball game? 3. -

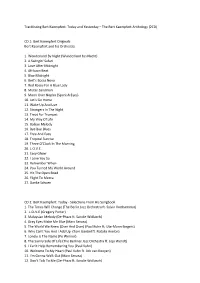

Tracklisting Bert Kaempfert: Today and Yesterday – the Bert Kaempfert Anthology (2CD)

Tracklisting Bert Kaempfert: Today and Yesterday – The Bert Kaempfert Anthology (2CD) CD 1: Bert Kaempfert Originals Bert Kaempfert and his Orchestra 1. Wonderland By Night (Wunderland bei Nacht) 2. A Swingin' Safari 3. Love After Midnight 4. Afrikaan Beat 5. Blue Midnight 6. Bert's Bossa Nova 7. Red Roses For A Blue Lady 8. Mister Sandman 9. Moon Over Naples (Spanish Eyes) 10. Let's Go Home 11. Wake Up And Live 12. Strangers In The Night 13. Treat For Trumpet 14. My Way Of Life 15. Balkan Melody 16. Bye Bye Blues 17. Free And Easy 18. Tropical Sunrise 19. Three O'Clock In The Morning 20. L.O.V.E. 21. Easy Glider 22. I Love You So 23. Remember When 24. You Turned My World Around 25. Hit The Open Road 26. Flight To Mecca 27. Danke Schoen CD 2: Bert Kaempfert: Today - Selections From His Songbook 1. The Times Will Change (The Berlin Jazz Orchestra ft. Sylvia Vrethammar) 2. L-O-V-E (Gregory Porter) 3. Malaysian Melody (De-Phazz ft. Sandie Wollasch) 4. Gray Eyes Make Me Blue (Marc Secara) 5. The World We Knew (Over And Over) (Paul Kuhn ft. Ute-Mann-Singers) 6. Why Can't You And I Add Up (Tom Gaebel ft. Natalia Avelon) 7. Lonely Is The Name (Pe Werner) 8. The Sunny Side Of Life (The Berliner Jazz Orchestra ft. Joja Wendt) 9. I Can't Help Remembering You (Paul Kuhn) 10. Welcome To My Heart (Paul Kuhn ft. Ack van Rooyen) 11. I'm Gonna Walk Out (Marc Secara) 12. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

The Music Industry and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture

The Music Industry: Demarcating Rhyme from Reason and the Fleecing of Consumer Culture I. Introduction The recording industry has a long history rooted deep in technological achievement and social undercurrents. In place to support such an infrastructure, is a lengthy list of technological advancements, political connections, lobbying efforts, marketing campaigns, and lawsuits. Ever since the early 20th century, record labels have embarked on a perpetual campaign to strengthen their control over recording artists and those technologies and distribution channels that fuel the success of such artists. As evident through the current draconian recording contracts currently foisted on artists, this campaign has often resulted in success. However, the rise of MTV, peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and even radio itself also proves that the labels have suffered numerous defeats. Unfortunately, most music listeners in the world have remained oblivious to the business practices employed by the recording industry. As long as the appearance of artistic freedom exists, as reinforced through the media, most consumers have typically been content to let sleeping dogs lie. Such a relaxed viewpoint, however, has resulted in numerous policies that have boosted industry profits at the expense of consumer dollars. Only when blatant coercion has occurred, as evidenced through the payola scandals of the 1950s, does the general public react in opposition to such practices. Ironically though, such outbursts of conscience have only served to drive payola practices further underground—hidden behind co-operative advertising agreements and outside promotion consultants. The advent of the Internet in the last decade, however, has thrown the dynamics of the recording industry into a state of disarray. -

Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021 a Blended Approach #Breconconf2021

Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021 A Blended Approach #BreconConf2021 Friday 8th to Friday 15th October 2021 For all teachers of Physics… join the Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021, this year between 8th – 15th October 2021. A fabulous free week of presentations and workshops for teachers, technicians and PGCE students with opportunities to network with colleagues. We will offer workshops shows and presentations between 1.30pm and 3pm each afternoon and 4pm until 8pm each evening Monday – Friday, as well as a quiz, a trek and workshops at an Alpaca Farm in the Brecon Beacons on Saturday morning (10:30am – 3.30pm), an opportunity to discuss the relationship between Physics and faith, networking opportunities with colleagues from Ireland and New Zealand – and a virtual tour of Penderyn Whisky Distillery in the heart of the Brecon Beacons. Please join us for a full week of workshops and inspiring lectures, which include: ‘Materials in Action’ (Dr Diane Aston, IOM3); ‘The Digital Century’ (Professor Neil Stansfield, National Physical Laboratory); ‘From cat skin to submarines – soft materials that are a bit of a stretch’ (Professor Helen F Gleeson, Leeds University) and ‘From Deep Space to Deep Impact: bringing the solar system down to Earth’ (Professor Paul Roche, Cardiff University). Workshops will include: ‘Keeping up the Momentum’; ’Physics, weather and forecasting’; ‘Tones, Tines and Tings’ and ‘What alpacas and other animals can teach us about Physics’. Technicians are welcome to attend all the events and we will also be hosting a technicians event: ‘The Physics Prep Room’ on Thursday 14th October. FREE registration via Eventbrite is at welshphysicsteachersconference2021.eventbrite.co.uk Please encourage colleagues from other schools and organisations to attend. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Exhibit O-137-DP

Contents 03 Chairman’s statement 06 Operating and Financial Review 32 Social responsibility 36 Board of Directors 38 Directors’ report 40 Corporate governance 44 Remuneration report Group financial statements 57 Group auditor’s report 58 Group consolidated income statement 60 Group consolidated balance sheet 61 Group consolidated statement of recognised income and expense 62 Group consolidated cash flow statement and note 63 Group accounting policies 66 Notes to the Group financial statements Company financial statements 91 Company auditor’s report 92 Company accounting policies 93 Company balance sheet and Notes to the Company financial statements Additional information 99 Group five year summary 100 Investor information The cover of this report features some of the year’s most successful artists and songwriters from EMI Music and EMI Music Publishing. EMI Music EMI Music is the recorded music division of EMI, and has a diverse roster of artists from across the world as well as an outstanding catalogue of recordings covering all music genres. Below are EMI Music’s top-selling artists and albums of the year.* Coldplay Robbie Williams Gorillaz KT Tunstall Keith Urban X&Y Intensive Care Demon Days Eye To The Telescope Be Here 9.9m 6.2m 5.9m 2.6m 2.5m The Rolling Korn Depeche Mode Trace Adkins RBD Stones SeeYou On The Playing The Angel Songs About Me Rebelde A Bigger Bang Other Side 1.6m 1.5m 1.5m 2.4m 1.8m Paul McCartney Dierks Bentley Radja Raphael Kate Bush Chaos And Creation Modern Day Drifter Langkah Baru Caravane Aerial In The Backyard 1.3m 1.2m 1.1m 1.1m 1.3m * All sales figures shown are for the 12 months ended 31 March 2006. -

Sandbox MUSIC MARKETING for the DIGITAL ERA Issue 98 | 4Th December 2013

Sandbox MUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA Issue 98 | 4th December 2013 Nordic lights: digital marketing in the streaming age INSIDE… Campaign Focus Sweden and Norway are bucking PAGE 5 : the trend by dramatically Interactive video special >> growing their recorded music Campaigns incomes and by doing so PAGE 6 : through streaming. In countries The latest projects from the where downloading is now a digital marketing arena >> digital niche, this has enormous implications for how music Tools will be marketed. It is no longer PAGE 7: about focusing eff orts for a few RebelMouse >> weeks either side of a release but Behind the Campaign rather playing the long game and PAGES 8 - 10: seeing promotion as something Primal Scream >> that must remain constant rather Charts than lurch in peaks and troughs. The Nordics are showing not just PAGE 11: where digital marketing has had Digital charts >> to change but also why other countries need to be paying very close attention. Issue 98 | 4th December 2013 | Page 2 continued… In 2013, alongside ABBA, black metal and OK; they still get gold- and platinum-certiied CEO of Sweden’s X5 Music latpack furniture, Sweden is now also singles and albums based on streaming Group, explains. “The known internationally for music streaming. revenues [adjusted].” marketing is substantially It’s not just that Spotify is headquartered di erent as you get paid in Stockholm; streaming has also famously Streaming is changing entirely the when people listen, not when turned around the fortunes of the Swedish marketing narrative they buy. You get as much recorded music industry. -

Declan Mckenna Brings “Protest Songs”

June 1, 2018 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT 17 Declan McKenna brings “protest songs” to MN Cari Spencer all loved this artist who isn’t very well- moving along as they sung the Editor in Chief known,” junior Alexis Mullen said. “We anthem back to him. were taking pictures at the wall and every- Outside of an unassuming beige build- one was cheering us on saying ‘Yes! Slay!’ For reasons beside the name itself, ing, a line of teenagers dawning Fresh It was just a great kind of community.” “The Kids Don’t Wanna Come Prince of Bel-Air-esque windbreakers and Home” was the perfect start to the mom jeans stretched all the way out to the Declan McKenna was the main event of concert; in an interview with New street, waiting to pour into the Burnsville the night. Before he took the stage, he was Musical Express, McKenna said Civic Center on March 13. Two hours opened by Chappel Roan, a female singer that the song is about young peo- later, they would see a 19-year-old indie from Missouri who made many new fans, ple being a movement of change artist from London dance around the Ga- judging from the various “your voice is despite the darkness in the world. rage stage in a sparkly bowler hat and gold iconic!” screams that sprung out from the The rest of the concert seemed to crowd. She played a few songs from her live out that meaning. From “Beth- tights. But for now, they waited, buzzing Photo/ Cari Spencer from excitement, or perhaps the cold. -

Doing Sound Slaten Dissertation Deposit

Doing Sound: An Ethnography of Fidelity, Temporality and Labor Among Live Sound Engineers Whitney Slaten Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Whitney Slaten All rights reserved ABSTRACT Doing Sound: An Ethnography of Fidelity, Temporality and Labor Among Live Sound Engineers Whitney Slaten This dissertation ethnographically represents the work of three live sound engineers and the profession of live sound reinforcement engineering in the New York City metropolitan area. In addition to amplifying music to intelligible sound levels, these engineers also amplify music in ways that engage the sonic norms associated with the pertinent musical genres of jazz, rock and music theater. These sonic norms often overdetermine audience members' expectations for sound quality at concerts. In particular, these engineers also work to sonically and visually mask themselves and their equipment. Engineers use the term “transparency” to describe this mode of labor and the relative success of sound reproduction technologies. As a concept within the realm of sound reproduction technologies, transparency describes methods of reproducing sounds without coloring or obscuring the original quality. Transparency closely relates to “fidelity,” a concept that became prominent throughout the late nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries to describe the success of sound reproduction equipment in making the quality of reproduced sound faithful to its original. The ethnography opens by framing the creative labor of live sound engineering through a process of “fidelity.” I argue that fidelity dynamically oscillates as struggle and satisfaction in live sound engineers’ theory of labor and resonates with their phenomenological encounters with sounds and social positions as laborers at concerts. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

Lost in Vagueness

LOST IN VAGUENESS THE ULTIMATE UNTOLD GLASTONBURY FESTIVAL STORY www.lostinvagueness.com A debut music feature documentary by Sofia Olins Presented by Dartmouth Films The cultural crucible for the UK’s alternative arts scene Featuring Fatboy Slim, Suggs (Madness), Keith Allen and Kate Tempest SYNOPSIS // Short The film of Roy Gurvitz, creator of Lost Vagueness at Glastonbury and who, as Michael Eavis says, reinvigorated the festival. Exploring the dark, self-destructive side of creative talent. Medium Lost In Vagueness: The Ultimate Untold Glastonbury Festival Story The film of Roy Gurvitz, who created Lost Vagueness, at Glastonbury and who, as Michael Eavis says, reinvigorated the festival. With the decadence of 1920’s Berlin, but all in a muddy field. A story of the dark, self-destructive side of creativity and the personal trauma behind it. Long Lost In Vagueness: Lost In Vagueness: The Ultimate Untold Glastonbury Festival Story The film of Roy Gurvitz, who invented the Lost Vagueness area at Glastonbury and who, as Michael Eavis says, reinvigorated the festival. It’s a story of the dark, self-destructive side of creative talent and the personal trauma behind it. Anti-hero, Roy, and Glastonbury founder, Michael, became friends in the early 1990’s. Through their story, we retrace Britain’s sub-culture history, to see how a band of troublesome new age travellers came together to create Lost Vagueness. It was a place of opulence and decadence, and reminiscent of a permissive 1920’s Berlin, but all in a muddy field. As an anarchic, punk traveller, Roy scoured Europe searching for a community where he could escape his oppressive upbringing.