Effects of Vergence and Accommodative Responses on Viewer’S Comfort in Viewing 3D Stimuli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accommodation in the Holmes-Adie Syndrome by G

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.21.4.290 on 1 November 1958. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1958, 21, 290. ACCOMMODATION IN THE HOLMES-ADIE SYNDROME BY G. F. M. RUSSELL From the Neurological Research Unit, the National Hospital, Queen Square, London In 1936, Bramwell suggested that the title response to near and far vision respectively. But it "Holmes-Adie syndrome" be given to the clinical has also been noted that the reaction to convergence complex of a slowly reacting pupil and absent tendon may be remarkably wide in its range, considering reflexes in recognition of the descriptions by Holmes that it often follows a stage of complete paralysis (1931) and Adie (1932). Both authors had empha- (Strasburger, 1902). Not only is the reaction to sized the chief clinical features-dilatation of the convergence well preserved when compared to the pupil, apparent loss of the reaction to light, slow reaction to light, but it may in fact be excessive constriction and relaxation in response to near and (Alajouanine and Morax, 1938; Heersema and distant vision, and partial loss of the tendon reflexes. Moersch, 1939). In assessing the degree of tonicity Although the syndrome had been recognized wholly there are, therefore, two criteria: slowness ofguest. Protected by copyright. or in part many years previously (Strasburger, 1902; pupillary movement and preservation of the range Saenger, 1902; Nonne, 1902; Markus, 1906; Weill of movement. and Reys, 1926), credit must go to Adie for stressing Adler and Scheie (1940) showed that the tonic the benign nature of the disorder and distinguishing pupil constricts after the conjunctival instillation it clearly from neurosyphilis. -

Conjunctive and Disjunctive Eye Movements an Pupillary Response Performance for Objective Metrics in Acute Mtbi

Conjunctive and Disjunctive Eye Movements an Pupillary Response Performance for Objective Metrics in Acute mTBI Carey Balaban, PhD1 Michael Hoffer, MD2 Mikaylo Sczczupak MD2 Alex Kiderman, PhD3 1University of Pittsburgh, 2 University of Miami, 3Neuro Kinetics, Inc. Disclosures • Michael E. Hoffer and Carey D. Balaban have no conflicts of interest or financial interests to report • Alexander Kiderman is an employee and shareholder of Neuro Kinetics, Inc. • The views expressed in this talk are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Pittsburgh, University of Miami, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. 2 Why is mTBI a Topic for Otolaryngology? • Balance disorders often present • Co-morbidities similar to balance-migraine- anxiety • Vestibular, oculomotor and reaction time tests provide objective metrics for acute mTBI Precision Medicine • Current clinical nosology as a clinical descriptive template – Symptoms – Signs – “Biomarkers” • Establish etiologic nosology – Identify acute response processes – Identify longitudinal processes – Plan interventions appropriate to patients’ clinical trajectories ‘Plain Language’ mTBI Definition • Documented traumatic event • ‘Not Quite Right’ (‘NQR’ criterion) • How does one quantify ‘NQR’? 5 Conjunctive Eye Movements as Objective mTBI Metrics: Up to 2 Weeks Post-Injury Conjuctive (Conjugate) Eye Movements for mTBI Diagnosis • High Frequency Horizontal Vestibulo-ocular Reflex – Computer-controlled Head Impulse Test (crHIT) • Saccades – Antisaccade Task – Predictive Saccade Task • Optokinetic Response • Smooth Pursuit Key Measure Changes Across Sessions Key Measure Changes Across Sessions Background • Disconjugate eye movements (convergence and divergence) track objects that vary in depth over the binocular visual field. These eye movements can be measured objectively and are commonly affected following mTBI. -

Asymmetries of Dark and Bright Negative Afterimages Are Paralleled by Subcortical on and OFF Poststimulus Responses

1984 • The Journal of Neuroscience, February 22, 2017 • 37(8):1984–1996 Systems/Circuits Asymmetries of Dark and Bright Negative Afterimages Are Paralleled by Subcortical ON and OFF Poststimulus Responses X Hui Li,1,2 X Xu Liu,1,2 X Ian M. Andolina,1 Xiaohong Li,1 Yiliang Lu,1 Lothar Spillmann,3 and Wei Wang1 1Institute of Neuroscience, State Key Laboratory of Neuroscience, Key Laboratory of Primate Neurobiology, Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200031, China, 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200031, China, and 3Department of Neurology, University of Freiburg, 79085 Freiburg, Germany Humans are more sensitive to luminance decrements than increments, as evidenced by lower thresholds and shorter latencies for dark stimuli. This asymmetry is consistent with results of neurophysiological recordings in dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and primary visual cortex (V1) of cat and monkey. Specifically, V1 population responses demonstrate that darks elicit higher levels of activation than brights, and the latency of OFF responses in dLGN and V1 is shorter than that of ON responses. The removal of a dark or bright disc often generates the perception of a negative afterimage, and here we ask whether there also exist asymmetries for negative afterimages elicited by dark and bright discs. If so, do the poststimulus responses of subcortical ON and OFF cells parallel such afterimage asymmetries? To test these hypotheses, we performed psychophysical experiments in humans and single-cell/S-potential recordings in cat dLGN. Psychophysically, we found that bright afterimages elicited by luminance decrements are stronger and last longer than dark afterimages elicited by luminance increments of equal sizes. -

Cone Contributions to Signals for Accommodation and the Relationship to Refractive Error

Vision Research 46 (2006) 3079–3089 www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Cone contributions to signals for accommodation and the relationship to refractive error Frances J. Rucker ¤, Philip B. Kruger Schnurmacher Institute for Vision Research, State University of New York, State College of Optometry, 33 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036, USA Received 18 February 2005; received in revised form 7 April 2006 Abstract The accommodation response is sensitive to the chromatic properties of the stimulus, a sensitivity presumed to be related to making use of the longitudinal chromatic aberration of the eye to decode the sign of the defocus. Thus, the relative sensitivity to the long- (L) and middle-wavelength (M) cones may inXuence accommodation and may also be related to an individual’s refractive error. Accommodation was measured continuously while subjects viewed a sine wave grating (2.2 c/d) that had diVerent cone contrast ratios. Seven conditions tested loci that form a circle with equal vector length (0.27) at 0, 22.5, 45, 67.5, 90, 120, 145 deg. An eighth condition produced an empty Weld stimulus (CIE (x,y) co-ordinates (0.4554, 0.3835)). Each of the gratings moved at 0.2 Hz sinusoidally between 1.00 D and 3.00 D for 40 s, while the eVects of longitudinal chromatic aberration were neutralized with an achromatizing lens. Both the mean level of accommo- dation and the gain of the accommodative response, to sinusoidal movements of the stimulus, depended on the relative L and M cone sen- sitivity: Individuals more sensitive to L-cone stimulation showed a higher level of accommodation (p D 0.01; F D 12.05; ANOVA) and dynamic gain was higher for gratings with relatively more L-cone contrast. -

Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction

OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION Doctors of optometry are independent primary health care providers who examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as diagnose related systemic conditions. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approximately 36,000 full-time-equivalent doctors of optometry currently in practice in the United States. Optometrists practice in more than 6,500 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care providers in more than 3,500 communities. The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH ACCOMMODATIVE AND VERGENCE DYSFUNCTION Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D., Principal Author Carole R. Burns, O.D. Susan A. Cotter, O.D. Kent M. Daum, O.D., Ph.D. John R. Griffin, M.S., O.D. Mitchell M. Scheiman, O.D. Revised by: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D. December 2010 Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. -

A Single Coordinate Framework for Optic Flow and Binocular Disparity

A coordinate framework for optic flow and disparity Glennerster and Read A single coordinate framework for optic flow and binocular disparity 1¶* 2¶ Andrew Glennerster and Jenny C.A. Read 1 School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, University of Reading, Reading RG6 6AL 2 Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, NE2 4HH ¶ These authors contributed equally to this work. * Corresponding author. Email [email protected] (AG) A coordinate framework for optic flow and disparity Glennerster and Read Abstract Optic flow is two dimensional, but no special qualities are attached to one or other of these dimensions. For binocular disparity, on the other hand, the terms 'horizontal' and 'vertical' disparities are commonly used. This is odd, since binocular disparity and optic flow describe essentially the same thing. The difference is that, generally, people tend to fixate relatively close to the direction of heading as they move, meaning that fixation is close to the optic flow epipole, whereas, for binocular vision, fixation is close to the head-centric midline, i.e. approximately 90 degrees from the binocular epipole. For fixating animals, some separations of flow may lead to simple algorithms for the judgement of surface structure and the control of action. We consider the following canonical flow patterns that sum to produce overall flow: (i) ‘towards’ flow, the component of translational flow produced by approaching (or retreating from) the fixated object, which produces pure radial flow on the retina; (ii) ‘sideways’ flow, the remaining component of translational flow, which is produced by translation of the optic centre orthogonal to the cyclopean line of sight and (iii) ‘vergence’ flow, rotational flow produced by a counter-rotation of the eye in order to maintain fixation. -

Do You Really Need Your Oblique Muscles? Adaptations and Exaptations

SPECIAL ARTICLE Do You Really Need Your Oblique Muscles? Adaptations and Exaptations Michael C. Brodsky, MD Background: Primitive adaptations in lateral-eyed ani- facilitate stereoscopic perception in the pitch plane. It also mals have programmed the oblique muscles to counter- recruits the oblique muscles to generate cycloversional rotate the eyes during pitch and roll. In humans, these saccades that preset torsional eye position immediately torsional movements are rudimentary. preceding volitional head tilt, permitting instantaneous nonstereoscopic tilt perception in the roll plane. Purpose: To determine whether the human oblique muscles are vestigial. Conclusions: The evolution of frontal binocular vision has exapted the human oblique muscles for stereo- Methods: Review of primitive oblique muscle adapta- scopic detection of slant in the pitch plane and nonste- tions and exaptations in human binocular vision. reoscopic detection of tilt in the roll plane. These exap- tations do not erase more primitive adaptations, which Results: Primitive adaptations in human oblique muscle can resurface when congenital strabismus and neuro- function produce rudimentary torsional eye move- logic disease produce evolutionary reversion from exap- ments that can be measured as cycloversion and cyclo- tation to adaptation. vergence under experimental conditions. The human tor- sional regulatory system suppresses these primitive adaptations and exaptively modulates cyclovergence to Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:820-828 HE HUMAN extraocular static counterroll led Jampel9 to con- muscles have evolved to clude that the primary role of the oblique meet the needs of a dy- muscles in humans is to prevent torsion. namic, 3-dimensional vi- So the question is whether the human ob- sual world. -

Pupils and Near Vision

PUPILS AND NEAR VISION Akilesh Gokul PhD Research Fellow Department of Ophthalmology Iris Anatomy Two muscles: • Radially oriented dilator (actually a myo-epithelium) - like the spokes of a wagon wheel • Sphincter/constrictor Pupillary Reflex • Size of pupil determined by balance between parasympathetic and sympathetic input • Parasympathetic constricts the pupil via sphincter muscle • Sympathetic dilates the pupil via dilator muscle • Response to light mediated by parasympathetic; • Increased innervation = pupil constriction • Decreased innervation = pupil dilation Parasympathetic Pathway 1. Three major divisions of neurons: • Afferent division 2. • Interneuron division • Efferent division Near response: • Convergence 3. • Accommodation • Pupillary constriction Pupil Light Parasympathetic – Afferent Pathway 1. • Retinal ganglion cells travel via the optic nerve leaving the optic tracts 2. before the LGB, and synapse in the pre-tectal nucleus. 3. Pupil Light Parasympathetic – Efferent Pathway 1. • Pre-tectal nucleus nerve fibres partially decussate to innervate both Edinger- 2. Westphal (EW) nuclei. • E-W nucleus to ipsilateral ciliary ganglion. Fibres travel via inferior division of III cranial nerve to ciliary ganglion via nerve to inferior oblique muscle. 3. • Ciliary ganglion via short ciliary nerves to innervate sphincter pupillae muscle. Near response: 1. Increased accommodation Pupil 2. Convergence 3. Pupillary constriction Sympathetic pathway • From hypothalamus uncrossed fibres 1. down brainstem to terminate in ciliospinal centre -

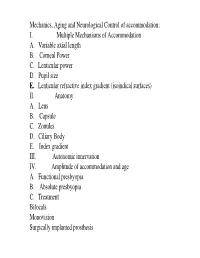

I. Multiple Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable Axial Length B

Mechanics, Aging and Neurological Control of accommodation: I. Multiple Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable axial length B. Corneal Power C. Lenticular power D. Pupil size E. Lenticular refractive index gradient (isoindical surfaces) II. Anatomy A. Lens B. Capsule C. Zonules D. Ciliary Body E. Index gradient III. Autonomic innervation IV. Amplitude of accommodation and age A. Functional presbyopia B. Absolute presbyopia C. Treatment Bifocals Monovision Surgically implanted prosthesis Course title - (VS217) Oculomotor functions and neurology Instructor - Clifton Schor GSI: James O’Shea, Michael Oliver & Aleks Polosukhina Schedule of lectures, exams and laboratories : Lecture hours 10-11:30 Tu Th; 5 min break at 11:00 Labs Friday the first 3 weeks Examination Schedule : Quizes: January 29; February 28 Midterm: February 14: Final March 13 Power point lecture slides are available on a CD Resources: text books, reader , website, handouts Class Website: Reader. Website http://schorlab.berkeley.edu Click courses 117 class page name VS117 password Hering,1 First Week: read chapters 16-18 See lecture outline in syllabus Labs begin this Friday, January 25 Course Goals Near Response - Current developments in optometry Myopia control – environmental, surgical, pharmaceutical and genetic Presbyopia treatment – amelioration and prosthetic treatment Developmental disorders (amblyopia and strabismus) Reading disorders Ergonomics- computers and sports vision Virtual reality and personal computer eye-ware Neurology screening- Primary care gate keeper neurology, systemic, endocrines, metabolic, muscular skeletal systems. Mechanics, Aging and Neurological Control of accommodation : I. Five Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable axial length B. Corneal Power and astigmatism C. Lenticular power D. Pupil size & Aberrations E. Lenticular refractive index gradient (isoindical surfaces) II. -

Convexity Bias and Perspective Cues in the Reverse-Perspective Illusion

Short Report i-Perception Convexity Bias and January-February 2016: 1–7 ! The Author(s) 2016 DOI: 10.1177/2041669516631698 Perspective Cues in the ipe.sagepub.com Reverse-Perspective Illusion Joshua J. Dobias Department of Psychology and Counseling, Marywood University, Scranton, PA, USA Thomas V. Papathomas Department of Biomedical Engineering and Laboratory of Vision Research, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, USA Vanja M. Vlajnic Department of Statistics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA Abstract The present experiment was designed to examine the roles of painted linear perspective cues, and the convexity bias that are known to influence human observers’ perception of three-dimensional (3D) objects and scenes. Reverse-perspective stimuli were used to elicit a depth-inversion illusion, in which far points on the stimulus appear to be closer than near points and vice versa, with a 2 (Type of stimulus) Â 2 (Fixation mark position) design. To study perspective, two types of stimuli were used: a version with painted linear perspective cues and a version with blank (unpainted) surfaces. To examine the role of convexity, two locations were used for the fixation mark: either in a locally convex or a locally concave part of each stimulus (painted and unpainted versions). Results indicated that the reverse-perspective illusion was stronger when the stimulus contained strong perspective cues and when observers fixated a locally concave region within the scene. Keywords Three-dimensional shape, reverse perspective, convexity bias, linear perspective, fixation location, visual context Introduction When viewing reverse-perspective stimuli (Wade & Hughes, 1999), painted linear perspective cues can compete with bottom-up monocular (motion parallax, shading, lens accommodation) and binocular (disparity, vergence angle) depth cues, thus creating a Corresponding author: Joshua J. -

Vergence Eye Movements in Responsetobinoculardisparity

letters to nature black-and-white bars at the neuron’s preferred orientation. The central region movements are elicited at ultrashort latencies1,2. Here we show of the stereogram completely covered the minimum response field. After that the same steps applied to dense anticorrelated patterns, in testing with RDS, neurons were classified as simple or complex on the basis of which each black dot in one eye is matched to a white dot in the the modulation in their firing to drifting gratings17. Of the 72 neurons, 57 were other eye, initiate vergence responses that are very similar, except tested in this way, of which 50 were complex cells and 7 were simple cells. that they are in the opposite direction. This sensitivity to the Analysis. For each neuron, the mean firing rate as a function of disparity (f(d)) disparity of anticorrelated patterns is shared by many disparity- was fitted with a Gabor function: selective neurons in cortical area V1 (ref. 3), despite the fact that human subjects fail to perceive depth in such stimuli4,5. These f ðdÞ¼Aexpð 2 ðd 2 DÞ2=2j2Þ cosð2pqðd 2 DÞþfÞþB data indicate that the vergence eye movements initiated at ultrashort by nonlinear regression, where A, q and f are the amplitude, spatial frequency latencies result solely from locally matched binocular features, and phase, respectively, of the cosine component, j is the standard deviation of and derive their visual input from an early stage of cortical the gaussian, D is a position offset, and B is the baseline firing rate. In our processing before the level at which depth percepts are elaborated. -

Restoration of Accommodation: New Perspectives Restauração Da Acomodação: Novas Perspectivas

Editorial Restoration of accommodation: new perspectives Restauração da acomodação: novas perspectivas TRACY SCHROEDER SWARTZ1, KAROLINNE MAIA ROCHA2, MITCH JACKSON3, DAVID HK MA4, DANIEL GOLDBERG5, ANNMARIE HIPSLEY6 Presbyopia is the loss of accommodative ability that occurs with age. Current accommodative theory postu- lates that the lens is primarily responsible for the refractive change that allows us to read. Our understanding of this process has grown substantially with the advent of new technologies, including ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), endoscopy, optical coherence tomography (OCT), ray-tracing and wavefront analysis. Goldberg’s Postu- late incorporates all elements of the zonular apparatus into the phenomenon of accommodation(1). The ciliary body contracts during accommodation. Biometry has shown that the lens thickness increases and the anterior chamber depth decreases(2). It has also demonstrated the lens capsule steepens, as the posterior-lens surface moves backwards(2). In addition, there is a decrease in the distance from scleral spur to the ora serrata. UBM identified an attach- ment zone of the posterior zonules adjacent to the ora, and contraction of these zonules is thought to be the etiology of the decrease in distance found with accommodation. This complex action of the zonules is suspec- ted to be reciprocal. As the same time the anterior zonules relax, reducing their tension on the lens such that the lens changes shape anteriorly, the posterior zonules contract, moving the posterior capsule backward. This vitreal-zonular complex stiffens with age, losing its elasticity(1-3). The age-related changes in these structures and their biomechanical interactions with the ciliary-lens complex may contribute to presbyopia(3).