A Single Coordinate Framework for Optic Flow and Binocular Disparity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conjunctive and Disjunctive Eye Movements an Pupillary Response Performance for Objective Metrics in Acute Mtbi

Conjunctive and Disjunctive Eye Movements an Pupillary Response Performance for Objective Metrics in Acute mTBI Carey Balaban, PhD1 Michael Hoffer, MD2 Mikaylo Sczczupak MD2 Alex Kiderman, PhD3 1University of Pittsburgh, 2 University of Miami, 3Neuro Kinetics, Inc. Disclosures • Michael E. Hoffer and Carey D. Balaban have no conflicts of interest or financial interests to report • Alexander Kiderman is an employee and shareholder of Neuro Kinetics, Inc. • The views expressed in this talk are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Pittsburgh, University of Miami, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. 2 Why is mTBI a Topic for Otolaryngology? • Balance disorders often present • Co-morbidities similar to balance-migraine- anxiety • Vestibular, oculomotor and reaction time tests provide objective metrics for acute mTBI Precision Medicine • Current clinical nosology as a clinical descriptive template – Symptoms – Signs – “Biomarkers” • Establish etiologic nosology – Identify acute response processes – Identify longitudinal processes – Plan interventions appropriate to patients’ clinical trajectories ‘Plain Language’ mTBI Definition • Documented traumatic event • ‘Not Quite Right’ (‘NQR’ criterion) • How does one quantify ‘NQR’? 5 Conjunctive Eye Movements as Objective mTBI Metrics: Up to 2 Weeks Post-Injury Conjuctive (Conjugate) Eye Movements for mTBI Diagnosis • High Frequency Horizontal Vestibulo-ocular Reflex – Computer-controlled Head Impulse Test (crHIT) • Saccades – Antisaccade Task – Predictive Saccade Task • Optokinetic Response • Smooth Pursuit Key Measure Changes Across Sessions Key Measure Changes Across Sessions Background • Disconjugate eye movements (convergence and divergence) track objects that vary in depth over the binocular visual field. These eye movements can be measured objectively and are commonly affected following mTBI. -

Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction

OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION Doctors of optometry are independent primary health care providers who examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as diagnose related systemic conditions. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approximately 36,000 full-time-equivalent doctors of optometry currently in practice in the United States. Optometrists practice in more than 6,500 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care providers in more than 3,500 communities. The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH ACCOMMODATIVE AND VERGENCE DYSFUNCTION Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D., Principal Author Carole R. Burns, O.D. Susan A. Cotter, O.D. Kent M. Daum, O.D., Ph.D. John R. Griffin, M.S., O.D. Mitchell M. Scheiman, O.D. Revised by: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D. December 2010 Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. -

Do You Really Need Your Oblique Muscles? Adaptations and Exaptations

SPECIAL ARTICLE Do You Really Need Your Oblique Muscles? Adaptations and Exaptations Michael C. Brodsky, MD Background: Primitive adaptations in lateral-eyed ani- facilitate stereoscopic perception in the pitch plane. It also mals have programmed the oblique muscles to counter- recruits the oblique muscles to generate cycloversional rotate the eyes during pitch and roll. In humans, these saccades that preset torsional eye position immediately torsional movements are rudimentary. preceding volitional head tilt, permitting instantaneous nonstereoscopic tilt perception in the roll plane. Purpose: To determine whether the human oblique muscles are vestigial. Conclusions: The evolution of frontal binocular vision has exapted the human oblique muscles for stereo- Methods: Review of primitive oblique muscle adapta- scopic detection of slant in the pitch plane and nonste- tions and exaptations in human binocular vision. reoscopic detection of tilt in the roll plane. These exap- tations do not erase more primitive adaptations, which Results: Primitive adaptations in human oblique muscle can resurface when congenital strabismus and neuro- function produce rudimentary torsional eye move- logic disease produce evolutionary reversion from exap- ments that can be measured as cycloversion and cyclo- tation to adaptation. vergence under experimental conditions. The human tor- sional regulatory system suppresses these primitive adaptations and exaptively modulates cyclovergence to Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:820-828 HE HUMAN extraocular static counterroll led Jampel9 to con- muscles have evolved to clude that the primary role of the oblique meet the needs of a dy- muscles in humans is to prevent torsion. namic, 3-dimensional vi- So the question is whether the human ob- sual world. -

Convexity Bias and Perspective Cues in the Reverse-Perspective Illusion

Short Report i-Perception Convexity Bias and January-February 2016: 1–7 ! The Author(s) 2016 DOI: 10.1177/2041669516631698 Perspective Cues in the ipe.sagepub.com Reverse-Perspective Illusion Joshua J. Dobias Department of Psychology and Counseling, Marywood University, Scranton, PA, USA Thomas V. Papathomas Department of Biomedical Engineering and Laboratory of Vision Research, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, USA Vanja M. Vlajnic Department of Statistics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA Abstract The present experiment was designed to examine the roles of painted linear perspective cues, and the convexity bias that are known to influence human observers’ perception of three-dimensional (3D) objects and scenes. Reverse-perspective stimuli were used to elicit a depth-inversion illusion, in which far points on the stimulus appear to be closer than near points and vice versa, with a 2 (Type of stimulus) Â 2 (Fixation mark position) design. To study perspective, two types of stimuli were used: a version with painted linear perspective cues and a version with blank (unpainted) surfaces. To examine the role of convexity, two locations were used for the fixation mark: either in a locally convex or a locally concave part of each stimulus (painted and unpainted versions). Results indicated that the reverse-perspective illusion was stronger when the stimulus contained strong perspective cues and when observers fixated a locally concave region within the scene. Keywords Three-dimensional shape, reverse perspective, convexity bias, linear perspective, fixation location, visual context Introduction When viewing reverse-perspective stimuli (Wade & Hughes, 1999), painted linear perspective cues can compete with bottom-up monocular (motion parallax, shading, lens accommodation) and binocular (disparity, vergence angle) depth cues, thus creating a Corresponding author: Joshua J. -

Vergence Eye Movements in Responsetobinoculardisparity

letters to nature black-and-white bars at the neuron’s preferred orientation. The central region movements are elicited at ultrashort latencies1,2. Here we show of the stereogram completely covered the minimum response field. After that the same steps applied to dense anticorrelated patterns, in testing with RDS, neurons were classified as simple or complex on the basis of which each black dot in one eye is matched to a white dot in the the modulation in their firing to drifting gratings17. Of the 72 neurons, 57 were other eye, initiate vergence responses that are very similar, except tested in this way, of which 50 were complex cells and 7 were simple cells. that they are in the opposite direction. This sensitivity to the Analysis. For each neuron, the mean firing rate as a function of disparity (f(d)) disparity of anticorrelated patterns is shared by many disparity- was fitted with a Gabor function: selective neurons in cortical area V1 (ref. 3), despite the fact that human subjects fail to perceive depth in such stimuli4,5. These f ðdÞ¼Aexpð 2 ðd 2 DÞ2=2j2Þ cosð2pqðd 2 DÞþfÞþB data indicate that the vergence eye movements initiated at ultrashort by nonlinear regression, where A, q and f are the amplitude, spatial frequency latencies result solely from locally matched binocular features, and phase, respectively, of the cosine component, j is the standard deviation of and derive their visual input from an early stage of cortical the gaussian, D is a position offset, and B is the baseline firing rate. In our processing before the level at which depth percepts are elaborated. -

Grey Mono Family Overview

Grey Mono Family Overview Styles About the Font LL Grey is a sans serif born of a screen-friendly appearance. As Grey Mono Light French grotesque, with all the with his previous efforts LL Purple rude, cabaret-like stroke endings and LL Brown, Aurèle used a his- of the genre. First called AS Gold, toric predecessor for formal cues, Grey Mono Light Italic the typeface made its debut as but brought his signature surgi- part of Aurèle Sack’s diploma pro- cal precision to its rendering. The Grey Mono Book ject at ECAL in 2004. result is a pleasant widening of the Now distilled and extended into idiosyncratic proportions of 19th Grey Mono Book Mono a playful yet highly readable text century grotesques. font, LL Grey has a contemporary, Scripts Cyrillic кириллица File Formats Opentype CFF, Truetype, WOFF, WOFF2 Greek Ελληνικά Design Aurèle Sack (2020 – 2021) Contact General inquiries: Lineto GmbH Paneuropean abc абв αβγ [email protected] Lutherstrasse 32 CH-8004 Zürich Technical inquiries: Switzerland Separate [email protected] PDF Grey Sales & licensing inquiries: www.lineto.com [email protected] LL Grey Mono – Specimen 2 Lineto Type Foundry Glyph Overview Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q Cyrillic А а Б б В в Г г Ѓ ѓ Ґ ґ Д д Е е Ё R S T U V W X Y Z ё Ж ж З з И и Й й К к Ќ ќ Л л М м Н н О о П п Р р С с Т т У у Ў ў Ф Lowercase a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q ф Х х Ч ч Ц ц Ш ш Щ щ Џ џ Ъ ъ Ы ы r s ß t u v w x y z Ь ь Љ љ Њ њ Ѕ ѕ Є є Э э І і Ї ї Ј Proportional, ј Ћ ћ Ю ю Я я Ђ ђ Ѣ ѣ Ғ ғ Қ қ Ң ң Mono Figures 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ү ү Ұ ұ Ҳ ҳ Һ һ Ә ә Ө ө Ligatures fi fl Greek Α α Β β Γ γ Δ δ Ε ε Ζ ζ Η η Θ θ Ι ι Κ κ Extented Character set À à Á á Â â Ã ã Ä ä Å å Ā ā Ă ă Ą Λ λ Μ μ Ν ν Ξ ξ Ο ο Π π Ρ ρ Σ σ Τ τ ą Ǻ ǻ Ǽ ǽ Æ æ Ç ç Ć ć Ĉ ĉ Ċ ċ Č č Υ υ Φ φ Χ χ Ψ ψ Ω ω Σ ς Α ά Ε έ Η ή Ι ί Ď ď Đ đ È è É é Ê ê Ë ë Ē ē Ĕ ĕ Ė Ο ό Υ ύ Ω ώ Ϊ ϊ Ϋ ϋ Ϊ ΰ ė Ę ę Ě ě Ĝ ĝ Ğ ğ Ġ ġ Ģ ģ Ĥ ĥ Ħ ħ Punctuation ( . -

1 Role of Accommodation in Clinical Measures of Proximal Vergence

Role of Accommodation in Clinical Measures of Proximal Vergence Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Fenton Graduate Program in Vision Science The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee Nicklaus Fogt, O.D., M.S., PhD, Advisor Catherine McDaniel, O.D., M.S. Donald Mutti, O.D., PhD 1 Copyrighted by Rachel Fenton 2019 2 Abstract Proximal vergence is the subtype of vergence that is stimulated by visual cues other than blur and disparity. There are two major clinical methods to assess proximal vergence. In one of these methods, termed the AC/A differencing method, proximal vergence is determined by calculating the difference in vergence change from the far-near AC/A method and the vergence change from the gradient AC/A method (equated for the accommodative demand). In the other method, termed the +2.50D method, the change in vergence posture between distance viewing and near viewing through a +2.50D lens is calculated. In assessing these values, it is typically assumed that response accommodation matched the change in accommodative demand from distance to near, which would be 2.50D for a 40cm near viewing distance. However, individuals often do not alter their accommodation by the amount of the accommodative demand. Therefore, proximal values calculated using accommodative responses might vary from proximal values that are calculated using the accommodative demand. The purpose of the present research is to determine the extent to which response accommodation could influence these methods of assessing proximal vergence, in order to better understand how proximal vergence is measured and therefore to better understand the relationship between proximal vergence and the other vergence subtypes in future studies. -

Effect of Sustained Cyclovergence on Eye Alignment: Rapid Torsional Phoria Adaptation

Effect of Sustained Cyclovergence on Eye Alignment: Rapid Torsional Phoria Adaptation Matthew J. Taylor,1 Dale C. Roberts,1,2 and David S. Zee1,2 PURPOSE. To describe adaptive changes in torsional alignment that follow sustained cyclovergence in healthy humans. METHODS. Eye movements were recorded binocularly from four healthy subjects using dual-coil scleral annuli. Cyclovergence movements were evoked over periods of 30 to 150 seconds using a stereoscopic display, presenting gratings of lines arranged horizontally, vertically, or at 45°, subtending angles of up to 48°. In- and excyclodisparities of 5° were introduced and removed in a single-step fashion. After stimulation, the time course and magnitude of the decay in cyclovergence was compared with the subject either in darkness or viewing a baseline stimulus of zero cyclodis- parity. RESULTS. As reported previously, the cyclovergence response to incyclodisparities was greater than to excyclodisparities. After sustained excyclovergence, however, in all subjects and in response to all orientations of the gratings, the decay in darkness was incomplete, implying an adaptive change in torsional alignment. In response to the horizontal gratings, for incyclovergence there was also an incomplete decay in darkness but to a lesser degree than in response to excyclovergence, and in only three of four subjects. The incyclovergence evoked by the oblique and vertical gratings was of small magnitude, and its decay was unaffected by the presence or absence of a visual stimulus. CONCLUSIONS. After sustained cyclovergence, its decay in the absence of a visual stimulus may be incomplete. The residual component may be interpreted, by analogy with horizontal and vertical vergence, as reflecting so-called phoria adaptation for torsional alignment. -

Vertical Fusional Vergence the Key to Dissociated Vertical Deviation

CLINICAL SCIENCES Vertical Fusional Vergence The Key to Dissociated Vertical Deviation Edward W. Cheeseman, Jr, MD; David L. Guyton, MD Objectives: To test the previous findings of Enright that value of torsional shift was 1.15° ± 0.76° in the expected disparity-induced vertical vergence is mediated primar- direction. ily by the oblique muscles, and to relate this normal eye movement pattern to the eye movement pattern seen in Conclusions: Vertical fusional vergences in this study subjects with dissociated vertical deviation. were produced primarily by the oblique extraocular muscles. The eye movement patterns of these vertical Methods: Sixteen normal volunteers underwent 55 mea- vergences in normal subjects are qualitatively similar to surements of the cycloversion associated with prism- those seen in recordings of patients with dissociated induced vertical vergence using an afterimage appara- vertical deviation. Dissociated vertical deviation thus tus. A Vernier scale measured the direction and magnitude seems to be an exaggeration of a normally occurring eye of the torsional shift that occurred with recovery of fu- movement pattern. The cyclovertical component of dis- sion on removal of a 3– or 4–prism diopter prism. sociated vertical deviation may help stabilize the fixing eye by damping vertical nystagmus, while the accompa- Results: Of the 55 trials, the directions of torsional shift nying hypertropia is an incidental and undesirable side were consistent with the oblique muscles being the pri- effect. mary mediators of vertical fusional vergence in 51 (93%) (P = .03 using a binomial distribution). The mean ± SD Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1188-1191 ISSOCIATED vertical devia- noted vertically divergent eye move- tion (DVD) is an enig- ments that were accompanied by a con- matic motility disorder jugate cycloversion. -

Chapter 6 Visual Perception

Chapter 6 Visual Perception Steven M. LaValle University of Oulu Copyright Steven M. LaValle 2019 Available for downloading at http://vr.cs.uiuc.edu/ 154 S. M. LaValle: Virtual Reality Chapter 6 Visual Perception This chapter continues where Chapter 5 left off by transitioning from the phys- iology of human vision to perception. If we were computers, then this transition might seem like going from low-level hardware to higher-level software and algo- rithms. How do our brains interpret the world around us so effectively in spite of our limited biological hardware? To understand how we may be fooled by visual stimuli presented by a display, you must first understand how our we perceive or interpret the real world under normal circumstances. It is not always clear what we will perceive. We have already seen several optical illusions. VR itself can be Figure 6.1: This painting uses a monocular depth cue called a texture gradient to considered as a grand optical illusion. Under what conditions will it succeed or enhance depth perception: The bricks become smaller and thinner as the depth fail? increases. Other cues arise from perspective projection, including height in the vi- Section 6.1 covers perception of the distance of objects from our eyes, which sual field and retinal image size. (“Paris Street, Rainy Day,” Gustave Caillebotte, is also related to the perception of object scale. Section 6.2 explains how we 1877. Art Institute of Chicago.) perceive motion. An important part of this is the illusion of motion that we perceive from videos, which are merely a sequence of pictures. -

Speed and Accuracy of Saccades, Vergence and Combined Eye Movements in Subjects with Strabismus Before and After Eye Surgery

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Vision Research 49 (2009) 460–469 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vision Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Speed and accuracy of saccades, vergence and combined eye movements in subjects with strabismus before and after eye surgery Maria Pia Bucci a,*, Dominique Brémond-Gignac a,b, Zoï Kapoula a a IRIS FRE 3154, CNRS, Pôle chirurgie ORL-OPH, Hôpital Robert Debré, Paris, France b Hôpital Robert Debré, Service d’Ophtalmologie, 48 Bld Sérurier, 75019 Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The purpose of the study was to examine spatio-temporal characteristics of horizontal eye move- Received 28 August 2008 ments in the natural space (saccade, vergence and combined movements) in young subjects with Received in revised form 4 December 2008 early onset convergent or divergent strabismus. Nine young subjects (8–20 years old) were tested: three with divergent strabismus, six with convergent strabismus. A standard paradigm was used to elicit pure horizontal saccades at far and at close viewing distance, pure vergence along the median Keywords: plane (convergence and divergence) and saccades combined with vergence movements. Horizontal Strabismus eye movements from both eyes were recorded by a photoelectric device. Eye movements were Saccades recorded before surgery, and, for the majority of the subjects, two times after surgery. Before surgery Vergence Combined movements the accuracy of convergence and divergence movements in their pure or combined form was poor Eye surgery with respect to normal values. The mean velocity of convergence was also abnormally slow. -

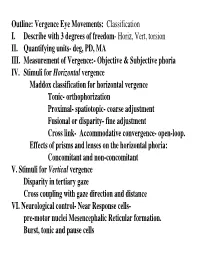

Vergence Eye Movements: Classification I

Outline: Vergence Eye Movements: Classification I. Describe with 3 degrees of freedom - Horiz, Vert, torsion II. Quantifying units- deg, PD, MA III. Measurement of Vergence:- Objective & Subjective phoria IV. Stimuli for Horizontal vergence Maddox classification for horizontal vergence Tonic- orthophorization Proximal- spatiotopic- coarse adjustment Fusional or disparity- fine adjustment Cross link- Accommodative convergence- open-loop. Effects of prisms and lenses on the horizontal phoria: Concomitant and non-concomitant V. Stimuli for Vertical vergence Disparity in tertiary gaze Cross coupling with gaze direction and distance VI. Neurological control- Near Response cells- pre-motor nuclei Mesencephalic Reticular formation. Burst, tonic and pause cells Outline: Vergence Eye Movements I. Describe with 3 degrees of freedom II. Quantifying units III. Measurement Objective Subjective IV. Maddox classification for horizontal vergence V. Neural control Two classes of binocular eye movements: Version movement Vergence movement Same direction Opposite direction Conjugate rotation Disjunctive rotation Vergence has three degrees of freedom Units for quantifying vergence: 1) Degrees 2) Prism Diopters (∆ ) = 100 x tan Degrees 3) Meter Angle (MA) = 1/VDm ∆ = MA x IPD cm e.g. 15 ∆ = 2.5 x 6.0 cm MA units are quantitatively similar to Diopter units of accommodation. MA are independent of the inter-pupillary distance. MA only apply to symmetrical convergence αp VD ∆? = 100 x tan pα tanp=IPD/VDα IPD by substitution ∆? =100XIPDm/VDm; IPDmX100=IPDcm ∆? = IPD cm / VD m Iso-Vergence Circle Iso-Version Lines A B Points A and B have the same Vergence angle. So do Points C and D. They lie on an iso- C vergence circle D Points A and C have the same Version angle.