Underneath Her Pantsuit: a Reflection on Hanna Rosin’S the End of Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fromcelebration Tocelebration

FromCelebration toCelebration Dress Code for Academic Events This guide introduces the dress code for academic events and festivities at Lappeenranta University of Technology. These festivities include the public defence of a dissertation, the post-doctoral karonkka banquet, and the conferment. Lappeenranta University of Technology was established in 1969 and, compared to many other universities, does not have long-standing traditions in academic festivities and especially doctoral conferment ceremonies. The following dress code should be observed at academic events at Lappeenranta University of Technology to establish in-house traditions. The instructions may, in some respects, differ from those of other universities. For instance with regard to colours worn by women, these instructions do not follow strict academic etiquette. 2 Contents Public Defence of a Dissertation 4 Conferment Ceremony 5 Dark Suit 6 Dark Suit, Accessories 8 Womens Semi-Formal Daytime Attire 10 White Tie 12 White Tie, Accessories 14 Womens Dark Suit, Doctoral Candidate 16 Womens Formal Daytime Attire, Doctor 18 Formal Evening Gown 20 Men's Informal Suit 22 Womens Informal Suit 24 Decorations 26 Doctoral Hat 28 Marshals 30 3 Public Defence of a Dissertation, Karonkka Banquet PUBLIC DEFENCE KARONKKA DOCTORAL CANDIDATE, White tie and tails, black vest White tie and tails, white vest if MALE (dark suit). ladies present (dark suit). Doctors: OPPONENT, doctoral hat. MALE CUSTOS, MALE p.12 p.12 DOCTORAL CANDIDATE, Womens dark suit, Formal evening gown, black. FEMALE high neckline, long sleeves, Doctors: doctoral hat. OPPONENT, suit with short skirt or trousers. FEMALE Opponent and custos: with CUSTOS, decorations. FEMALE p.16 p.20 CANDIDATES COMPANION, Semi-formal daytime attire, Formal evening gown, black. -

2016 Annual Meeting Dress Guidelines Western USA Lieutenancy

2016 Annual Meeting Dress Guidelines Western USA Lieutenancy DRESS CODE INFORMATION Gentlemen Gentlemen Clergy Knights Ladies Lady Investees Lady Guests Clergy THURSDAY Investees Guests Investees Hotel Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Church Church Church Church Appropriate Year of Mercy Pilgrimage Clericals Appropriate attire Appropriate attire Appropriate attire attire Gentlemen Gentlemen Clergy Knights Ladies Lady Investees Lady Guests Clergy FRIDAY Investees Guests Investees Hotel Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Church Church Church Church Appropriate Vigil Retreats Clericals Appropriate attire Appropriate attire Appropriate attire attire Gentlemen Gentlemen Clergy Knights Ladies Lady Investees Lady Guests Clergy SATURDAY Investees Guests Investees Hotel Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Resort Casual1 Dark Suit, White Dark Dress Dark Dress Dark Dress Shirt, Tie Dark Suit Dark Suit Alb Alb (NO jacket or Suit or Suit or Suit under Cape) Promotions & Cape Cape Stole of the Stole Memorial Mass (No Decorations) (No Decorations) Order Beret (Badge worn Mantilla to the right) White Gloves Black Gloves Black Shoes Black Shoes Black Shoes Black Shoes DRESS CODE INFORMATION Gentlemen Gentlemen Clergy Knights Ladies Lady Investees Lady Guests Clergy SUNDAY Investees Guests Investees Hotel Resort Casual1 -

CPE at the Races

2014 CPE at the Races! Speaker! Registration Form! ! Eric Crumbaugh, Pharm.D.! ! Director of Clinical Programs! Name:____________________________! Arkansas Pharmacists Association! Friday, February 28, 2014! Address:__________________________! Little Rock! ! Oaklawn Park - Hot Springs! City:_____________State:___Zip:______! The program will qualify for 2 hours of live CPE, provided E-mail:____________________________! by the Arkansas State Board of Pharmacy.! ! ! CPE at the Races Home Phone:_______________________! Work Phone:_______________________! Directions to Oaklawn - Take Arkansas Hwy 70/270 to the Cell Phone:________________________! Central Avenue exit. Go north on Central Avenue until you reach Oaklawn Park. Parking is on your own. The North ! Parking Lot is available for $2.00.! Registration Fees:! ! Enter Oaklawn Park through the North Entrance at the Group _____APA Member ($65)! Sales turnstile. Take the Club Level elevators and proceed to _____APA Non-Member ($165)! the “Arkansas Room.” Gates open at 9:00 a.m.! _____Guest of APA Member ($50)! ! Dress Code - Men must wear sports coat. _____Guest of APA Non-Member ($85)! Ladies must wear pantsuit or dress. Jeans, ! sportswear, and other leisure attire is not ! permitted. Card Type:_________________________! Credit Card#:_______________________! Expiration Date:_____________________! Total Amount:_______________________! Signature:_________________________! ! Register online at:! www.arrx.org! ! Mail or fax completed registration form to:! APA! 417 S. Victory ! Little Rock, AR 72201! (501) 372-0546 fax! Join pharmacists from Program all over Arkansas for supported continuing education by: and fun at the races! 9:30 - 11:30 a.m.! 11:45 a.m. - 1:30 p.m.! 1:30 p.m.! Improving Patient Outcomes Race Preview &! First Race Post Time! with Medication Therapy Lunch Buffet! Oaklawn Racetrack! Management (MTM)" Oaklawn Jockey Club" ! ! Eric Crumbaugh, Pharm.D." ! Never start the races on an An exciting day of racing Learning Objectives:! empty stomach. -

Reno High School Graduation Wednesday, June 12, 2019, 10:30 A.M

Reno High School Graduation Wednesday, June 12, 2019, 10:30 a.m. Lawlor Events Center MANDATORY Practice: June 3rd – 1:40 - 2:30 Large Gym (for students who do not have 7th period) To: Senior Class of 2019 Parents/Guardians of Graduating Senior Class Members From: Linda Feroah, Assistant Principal This information will be of use in planning and making the graduation ceremony successful: 1. After receiving your caps and gowns, PRESS THE GOWN. When worn, the gown should hang approximately 8 inches from the floor for all students. GOWNS ARE ALL BLUE THIS YEAR –NO RED GOWNS. 2. Prior to the graduation practice, return all textbooks and library books; pay all fines. These obligations must be met before 2:30 p.m. on Friday, May 31st. 3. GRAD REHEARSAL - There will be no rehearsal time at Lawlor so we are holding a mandatory rehearsal during 7th period Monday, June 3rd. Only students who have a 7th period will be excused from this rehearsal. Caps and gowns will also be distributed at this time. 4. On the day of the actual ceremony, please have your cap and gown on a hanger as this will be your ticket for entry into Lawlor. Please arrive no later than 9:30 am on Wednesday, June 12th. Grad speakers should arrive by 9:15 am so they have time to practice on stage. 5. All graduates are expected to dress appropriately for the ceremonies. The following guidelines are advised: A dress shirt with a collar and necktie, dress slacks, dress shoes and socks or wear a dress, a skirt and blouse, a pantsuit, dress slacks and blouse, dress shoes or low heels. -

Hudson High School 2021 Prom Guidelines Non Hudson Guest Guidelines

Hudson High School 2021 Prom Guidelines Non Hudson Guest Guidelines: Non-Hudson students attending prom as the guest of a junior or senior Hudson student must follow the same dress and behavior guidelines as Hudson High School student attendees. Students who wish to bring an out-of-town/out-of-school guest must provide the individual’s name, school attending or city of residence, graduation year to the principal/designee for approval at least ONE WEEK prior to prom. Out of-town students/guests must be under the age of 21. Students will not be able to purchase a ticket for an out-of-town or out-of district guest without prior principal approval. ALCOHOL AND OTHER INTOXICATING SUBSTANCES: Any student in possession of or under the influence of alcohol or other intoxicating substances will be asked to leave the premises, and law enforcement officers WILL be called to intervene. Any student or guest who arrives under the influence of intoxicating substances will not be allowed to enter the Prom and will be required to leave the premises. Any student who is reprimanded for infractions related to intoxicating substances WILL be subject to all Handbook penalties governing said infractions. GENERAL BEHAVIOR: Students and their guests will be expected to conduct themselves according to the Student Code of Conduct at all times. Any disrespectful, defiant, obscene, or obnoxious behavior by a student or his/her guest at the Prom will subject the student to all Handbook regulations governing inappropriate behavior. No refunds will be given for students who are asked to leave the Prom for Dress Code or Disciplinary violations. -

Georgia FCCLA Dress Code 2018 State Leadership Conference

Georgia FCCLA Dress Code 2018 State Leadership Conference FCCLA members are expected to display a professional image at all functions. Members should always be respectful to administrators, exhibitors, parents, advisers and other members. Advisers will ensure that students look professional and in appropriate attire at all times. Students in inappropriate clothes will be asked to change clothes before returning to the meeting. Activity Male Attire Female Attire Opening Session (Friday)* Black pants, black dress shoes, Black pants, black skirts (at least knee STAR Events Orientation white professional shirt (white length), black sheath dress, black dress (Friday)* FCCLA polo given at conference shoes, white professional shirt (white Closing Session (Sunday)* registration) FCCLA polo given at conference registration) Recognition Session (Saturday) Gala Black pants, black dress shoes, Black pants, black skirts (at least knee (Saturday) white professional shirt (white length), black sheath dress, black dress FCCLA polo given at conference shoes, white professional shirt (white registration) -or- FCCLA polo given at conference Dress shirt, neck tie, blazer or registration) suits, slacks, dress shoes and -or- socks; tuxedo is optional Dressy dress (must be fingertip length) or pantsuit, dress shoes. No cleavage, bare midriffs or bare backs extending below the waist Competitions (Saturday) Black pants, black dress shoes, Black pants, black skirts (at least knee white professional shirt (white length), black sheath dress, black dress FCCLA polo -

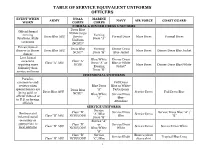

Table of Service Equivalent Uniforms Officers

TABLE OF SERVICE EQUIVALENT UNIFORMS OFFICERS EVENT WHEN NOAA MARINE ARMY NAVY AIR FORCE COAST GUARD WORN CORPS CORPS FORMAL & DINNER DRESS UNIFORMS Dress Blue Official formal NOAA Corps evening Evening Dress Blue ASU Service Formal Dress Mess Dress Formal Dress functions, State Dress “A” Uniform occasions (NCSU)* Private formal Dress Blue Evening Dinner Dress dinners or dinner Dress Blue ASU Mess Dress Dinner Dress Blue Jacket NCSU* Dress “B” Blue Jacket dances Less formal Blue/White Dinner Dress occasions Class “A” Class “A” ASU Dress “A” or Blue or White requiring more NCSU Mess Dress Dinner Dress Blue/White Evening Jacket* formality than Dress “B” service uniforms CEREMONIAL UNIFORMS Parades, ceremonies and Full Dress reviews when Blue Dress Blue or White- special honors are Dress Blue “A” Participants Dress Blue ASU Service Dress Full Dress Blue being paid, or NCSU* Blue/White Service Dress official visits of or “A” Blue- to U.S. or foreign Attendees officials SERVICE UNIFORMS Service Class “B” Service Dress Service Dress Blue “A” / Business and “A”/Blue Service Dress Class “B” ASU NCSU/ODU Blue “B” informal social Dress “B” occasions as Service “A” appropriate to Class “B” or Service Dress Class “B” ASU Service Dress Service Dress White local customs NCSU/ODU Blue/White White “B” Class “B” Service Blues w/short Service Khaki Tropical Blue Long Class “B” ASU NCSU/ODU “C”/Blue sleeve shirt 1 Dress “D” (w/or w/out Business and tie/tab) informal social Blues w/short occasions as Blue Dress Class “B” Summer sleeve shirt appropriate to -

Women in Pants: a Study of Female College Students Adoption Of

WOMEN IN PANTS: A STUDY OF FEMALE COLLEGE STUDENTS ADOPTION OF BIFURCATED GARMENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA FROM 1960 TO 1974 by CANDICE NICHOLE LURKER SAULS Under the direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst ABSTRACT This research presented new information regarding the adoption of bifurcated garments by female students at the University of Georgia from1960 to 1974. The primary objectives were to examine photographs of female students at the University of Georgia in The Pandora yearbooks as well as to review written references alluding to university female dress codes as well as regulations and guidelines. The photographs revealed that prior to 1968 women at UGA wore bifurcated garments for private activities taking place in dorms or at sorority houses away from UGA property. The study also showed an increase in frequency from 1968 to 1974 due to the abolishment of the dress code regulations. In reference to the specific bifurcated garments worn by female students, the findings indicated the dominance of long pants. This study offers a sample of the changes in women’s dress during the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s, which then showed more specifically how college women dressed in their daily lives across America. INDEX WORDS: Dress Codes, Mid Twentieth Century, University of Georgia, Women’s Dress WOMEN IN PANTS: A STUDY OF FEMALE COLLEGE STUDENTS ADOPTION OF BIFURCATED GARMENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA FROM 1960 TO 1974 by CANDICE NICHOLE LURKER SAULS B.S.F.C.S., The University of Georgia, 2005 B.S.F.C.S., The University of Georgia, 2007 -

Professional Dress

Professional Dress Purpose As you are on the hunt for an internship or job, remember that presentation counts! You want to be seen as a candidate that would represent the company well. For some companies a suit and tie may be daily attire, for others, business casual or even jeans may be acceptable. Learn what to wear and what not to wear below. Business Professional Women: Women have a little bit of room when it comes to professional dress. A matching pantsuit, skirt suit or even a professional dress and blazer can work. You will need to dress in business professional for career fairs, most interviews, and sometimes every day on the job. Remember, your pockets will likely be sewn shut when you purchase a new suit. Remove the thread using a seam ripper or small manicure scissors before wearing it out. In addition, there is often an “X” stitched on the back of your suit jacket at the vent(s), make sure to remove it before wearing. Remember the tips below to dress appropriately: • Skirts and dresses should be knee length • Blouses should not be too tight or low cut • Limited jewelry • Appropriate makeup • Polished shoes (flats or heels less than 2”, no open toe) Men: Men should expect to wear a tailored and dark colored suit (black, gray, navy etc.) when dressing in business professional attire. You will need to dress in business professional for career fairs, most interviews and sometimes every day on the job. Remember, your pockets will likely be sewn shut when you purchase a new suit. -

2015-State-Fashion-Show-Rules

2015 Texas 4-H Fashion Show Buying and Construction General Rules and Guidelines OVERVIEW The 4-H Fashion Show is designed to recognize 4-H members who have completed a Clothing and Textiles project. The following objectives are taught in the Clothing and Textiles project: knowledge of fibers and fabrics, wardrobe selection, clothing construction, comparison shopping, fashion interpretation, understanding of style, good grooming, poise in front of others, and personal presentation skills. PURPOSE The Fashion Show provides an opportunity for 4-H members to exhibit the skills learned in their project work. It also provides members an opportunity to increase their personal presentation skills. FASHION SHOW BUYING AND CONSTRUCTION 4-H Fashion Show at the county level is an optional activity that is open to all 4-H members who have completed a clothing project. Senior 4-H members who have completed and won at the district Fashion Show competition can compete at the Fashion Show during Texas 4-H Roundup. Each district may send one contestant from each of the four construction categories (Everyday Living, ReFashion, Semi-formal to Formal, and Theatre/Costume) and one contestant from each of the four buying categories (Business/Interview, Fantastic Fashion under $25, Semi-formal to Formal, and Special Interest). ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS The following requirements provide as fair an opportunity as possible for participation by as many outstanding 4-H members as possible. The requirements given below apply to senior members who plan to participate in the state contest. Failure to comply with the requirements will result in disqualification or penalty deductions from the final score. -

Maclay Upper School Does Not Have a Required Uniform Dress

Maclay Upper School does not have a required uniform dress; however, by his/her attendance at Maclay, a student and their parent/guardian agree to abide by the guidelines established by the school. The student in violation of the dress code will be subject to consequences defined below. Repeat violations may be subject to suspensions. The following specific guidelines must be observed. General Appearance No part of undergarments may be visible at any time. This includes, but is not limited to boxer shorts, briefs, bra straps and bralettes. No body piercing is allowed except for girls’ earrings. Hairstyle must not be extreme or distracting. Hair color must be a color that falls within the natural spectrum of hair color. A sense of modesty about one’s appearance when sitting in a classroom is expected of all. Clothing must fit appropriately Items not Permitted All forms of head coverings inside of buildings, except for religious reasons approved by the administration. Clothing with ragged edges or holes manufactured commercially or not. Clothing with large sections cut out manufactured commercially or not. Clothing that is sheer and/or tight as to reveal underwear or body parts. Clothing that is sexually suggestive or contains vulgar lettering, printing, or drawings. Depictions of or references to drugs, tobacco, or alcoholic beverages. Clothing with symbols that are considered offensive. *Fridays are Spirit Days at Maclay. Students will be encouraged to demonstrate school spirit by wearing a Maclay shirt, such as a team or club shirt. Rules for Specific Articles of Clothing: Pants Pants must fit at the waist. -

State Leadership Workshop Dress Code

2014 PA PENNSYLVANIA FBLA STATE LEADERSHIP WORKSHOP DRESS CODE The dress code approved by the PA FBLA Board of Directors for all FBLA functions, including the 2014 PA FBLA State Leadership Workshop is: The purpose of the dress code is to uphold the professional image of the Association and its members and to prepare students for the business world. Appropriate business attire is required for all attendees--advisers, members, and guests--for all general sessions, competitive events, caucusing, workshops, meal functions, and receptions. Attire for social functions shall be listed in the conference program. Delegates shall abide by the dress code established by the PA FBLA Board of Directors for all state functions. Delegates not adhering to the dress code shall not be admitted to the functions listed above. The specific dress code for all delegates shall be: Permitted for Gentlemen Business suit with collar dress shirt, and necktie or Sport coat, dress slacks, collared shirt, and necktie or Dress slacks, collared shirt, and necktie. Banded collar shirt may be worn only if sport coat or business suit is worn. Dress shoes and socks. Permitted for Ladies Business suit with blouse or Business pantsuit with blouse or Skirt or dress slacks with blouse or sweater or Business dress or Dress capris (below the knee) or dress gaucho (below the knee) with a coordinating jacket. Dress shoes. The length of ladies’ dresses, skirts, etc., shall be no shorter than 1 inch above the top of the ladies’ knees. Not Permitted for Ladies and Gentlemen Jewelry in visible body piercing, other than ears.