Young Fairy Place-Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

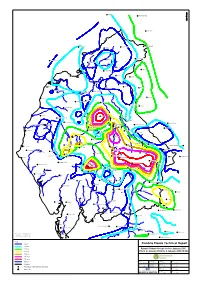

Cumbria Floods Technical Report

Braidlie Kielder Ridge End Kielder Dam Coalburn Whitehill Solwaybank Crewe Fell F.H. Catlowdy Wiley Sike Gland Shankbridge Kinmount House C.A.D.Longtown Walton Haltwhistle Fordsyke Farm Drumburgh Brampton Tindale Carlisle Castle Carrock Silloth Geltsdale Cumwhinton Knarsdale Abbeytown Kingside Blackhall Wood Thursby WWTW Alston STW Mawbray Calder Hall Westward Park Farm Broadfield House Haresceugh Castle Hartside Quarry Hill Farm Dearham Caldbeck Hall Skelton Nunwick Hall Sunderland WWTW Penrith Langwathby Bassenthwaite Mosedale Greenhills Farm Penrith Cemetery Riggside Blencarn Cockermouth SWKS Cockermouth Newton Rigg Penrith Mungrisdale Low Beckside Cow Green Mungrisdale Workington Oasis Penrith Green Close Farm Kirkby Thore Keswick Askham Hall Cornhow High Row Appleby Appleby Mill Hill St John's Beck Sleagill Brackenber High Snab Farm Balderhead Embankment Whitehaven Moorahall Farm Dale Head North Stainmore Summergrove Burnbanks Tel Starling Gill Brough Ennerdale TWks Scale Beck Brothers Water Honister Black Sail Ennerdale Swindale Head Farm Seathwaite Farm Barras Old Spital Farm St Bees Wet Sleddale Crosby Garrett Wastwater Hotel Orton Shallowford Prior Scales Farm Grasmere Tannercroft Kirkby Stephen Rydal Hall Kentmere Hallow Bank Peagill Elterwater Longsleddale Tebay Brathay Hall Seascale White Heath Boot Seathwaite Coniston Windermere Black Moss Watchgate Ravenstonedale Aisgill Ferry House Ulpha Duddon Grizedale Fisher Tarn Reservoir Kendal Moorland Cottage Sedburgh Tower Wood S.Wks Sedbusk Oxen Park Tow Hill Levens Bridge End Lanthwaite Grizebeck High Newton Reservoir Meathop Far Gearstones Beckermonds Beetham Hall Arnside Ulverston P.F. Leck Hall Grange Palace Nook Carnforth Crag Bank Pedder Potts No 2 Barrow in Furness Wennington Clint Bentham Summerhill Stainforth Malham Tarn This map is reproduced from the OS map by the Environment Agency with Clapham Turnerford the permission of the controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office, Crown Copyright. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Revision of Coniston Parish Plan 2017

REVISION OF CONISTON PARISH PLAN 2017 1 CONTENTS Background & Reason for Revision of Current Parish Plan 3 Update on Existing Parish Plan (2011/12) 4 - 8 Issues Identified from Survey Results with Action Plans:- Place 9 Walking 10 - 11 Transport 12 Car Parking 13 - 14 Highways 15 Housing 16 - 18 Living in Coniston 19 - 21 Future 22 – 23 Conclusion 24 Appendix – Contact details for local organisations 25 Useful Information 26 Occupancy restrictions in Coniston & Torver 27 - 28 2 BACKGROUND Location Coniston is a village in the county of Cumbria within the southern part of the Lake District National Park beside Coniston Water, the third longest lake in the Lake District. Coniston grew as a farming village and to serve local copper and slate mines. During the Victorian era it developed as a tourist location partially through the construction of a branch of the Furness Railway which closed in the late 1950’s / early 1960’s. Today, Coniston is a popular tourist resort with a thriving village community. The nearest large villages are Hawkshead 4 miles away and Ambleside 8 miles away. Local knowledge suggests that nearly 60% of the housing stock in Coniston is owned as a second home or let as holiday housing. There is a good range of local services and social amenities with a primary and secondary school, fire station, post office and shops with basic supplies. The main employment locally is based around agricultural and tourism with many other local businesses. Coniston has wide range of social and recreational opportunities. The population of the Parish is 928 (Census 2011). -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Kirkandrews on Esk: Introduction1

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an incomplete, interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/] Parish/township: KIRKANDREWS ON ESK Author: Fay V. Winkworth Date of draft: January 2013 KIRKANDREWS ON ESK: INTRODUCTION1 1. Description and location Kirkandrews on Esk is a large rural, sparsely populated parish in the north west of Cumbria bordering on Scotland. It extends nearly 10 miles in a north-east direction from the Solway Firth, with an average breadth of 3 miles. It comprised 10,891 acres (4,407 ha) in 1864 2 and 11,124 acres (4,502 ha) in 1938. 3 Originally part of the barony of Liddel, its history is closely linked with the neighbouring parish of Arthuret. The nearest town is Longtown (just across the River Esk in Arthuret parish). Kirkandrews on Esk, named after the church of St. Andrews 4, lies about 11 miles north of Carlisle. This parish is separated from Scotland by the rivers Sark and Liddel as well as the Scotsdike, a mound of earth erected in 1552 to divide the English Debatable lands from the Scottish. It is bounded on the south and east by Arthuret and Rockcliffe parishes and on the north east by Nicholforest, formerly a chapelry within Kirkandrews which became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1744. The border with Arthuret is marked by the River Esk and the Carwinley burn. 1 The author thanks the following for their assistance during the preparation of this article: Ian Winkworth, Richard Brockington, William Bundred, Chairman of Kirkandrews Parish Council, Gillian Massiah, publicity officer Kirkandrews on Esk church, Ivor Gray and local residents of Kirkandrews on Esk, David Grisenthwaite for his detailed information on buses in this parish; David Bowcock, Tom Robson and the staff of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle; Stephen White at Carlisle Central Library. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Index to Gallery Geograph

INDEX TO GALLERY GEOGRAPH IMAGES These images are taken from the Geograph website under the Creative Commons Licence. They have all been incorporated into the appropriate township entry in the Images of (this township) entry on the Right-hand side. [1343 images as at 1st March 2019] IMAGES FROM HISTORIC PUBLICATIONS From W G Collingwood, The Lake Counties 1932; paintings by A Reginald Smith, Titles 01 Windermere above Skelwith 03 The Langdales from Loughrigg 02 Grasmere Church Bridge Tarn 04 Snow-capped Wetherlam 05 Winter, near Skelwith Bridge 06 Showery Weather, Coniston 07 In the Duddon Valley 08 The Honister Pass 09 Buttermere 10 Crummock-water 11 Derwentwater 12 Borrowdale 13 Old Cottage, Stonethwaite 14 Thirlmere, 15 Ullswater, 16 Mardale (Evening), Engravings Thomas Pennant Alston Moor 1801 Appleby Castle Naworth castle Pendragon castle Margaret Countess of Kirkby Lonsdale bridge Lanercost Priory Cumberland Anne Clifford's Column Images from Hutchinson's History of Cumberland 1794 Vol 1 Title page Lanercost Priory Lanercost Priory Bewcastle Cross Walton House, Walton Naworth Castle Warwick Hall Wetheral Cells Wetheral Priory Wetheral Church Giant's Cave Brougham Giant's Cave Interior Brougham Hall Penrith Castle Blencow Hall, Greystoke Dacre Castle Millom Castle Vol 2 Carlisle Castle Whitehaven Whitehaven St Nicholas Whitehaven St James Whitehaven Castle Cockermouth Bridge Keswick Pocklington's Island Castlerigg Stone Circle Grange in Borrowdale Bowder Stone Bassenthwaite lake Roman Altars, Maryport Aqua-tints and engravings from -

SOUTH LAKELAND DISTRICT COUNCIL Valuation Bands

Appendix A SOUTH LAKELAND DISTRICT COUNCIL Valuation Bands BAND A BAND B BAND C BAND D BAND E BAND F BAND G BAND H £117.09 £136.60 £156.12 £175.63 £214.66 £253.69 £292.72 £351.26 CUMBRIA COUNTY COUNCIL Valuation Bands BAND A BAND B BAND C BAND D BAND E BAND F BAND G BAND H £774.33 £903.39 £1032.44 £1161.50 £1419.61 £1677.72 £1935.83 £2323.00 POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER Valuation Bands BAND A BAND B BAND C BAND D BAND E BAND F BAND G BAND H £136.44 £159.18 £181.92 £204.66 £250.14 £295.62 £341.10 £409.32 COUNCIL TAX FOR EACH PART OF THE DISTRICT Valuation Bands PARISH BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND A B C D E F G H £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ ALDINGHAM 1041.54 1215.14 1388.72 1562.32 1909.50 2256.68 2603.86 3124.64 ALLITHWAITE UPPER 1054.39 1230.13 1405.85 1581.59 1933.05 2284.52 2635.98 3163.18 ANGERTON 1043.32 1217.21 1391.09 1564.98 1912.75 2260.52 2608.30 3129.96 ARNSIDE 1051.10 1226.28 1401.46 1576.65 1927.02 2277.38 2627.75 3153.30 BARBON 1035.96 1208.63 1381.28 1553.95 1899.27 2244.59 2589.91 3107.90 BEETHAM 1041.47 1215.05 1388.63 1562.21 1909.37 2256.52 2603.68 3124.42 PARISH BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND BAND A B C D E F G H £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ BLAWITH & 1037.18 1210.04 1382.90 1555.77 1901.50 2247.22 2592.95 3111.54 SUBBERTHWAITE BROUGHTON EAST 1044.56 1218.66 1392.75 1566.85 1915.04 2263.23 2611.41 3133.70 BROUGHTON WEST 1043.32 1217.21 1391.09 1564.98 1912.75 2260.52 2608.30 3129.96 BURTON IN KENDAL 1042.22 1215.93 1389.63 1563.34 1910.75 2258.16 2605.56 3126.68 CARTMEL FELL 1043.74 1217.71 1391.66 1565.62 1913.53 2261.45 2609.36 -

Solway Country

Solway Country Solway Country Land, Life and Livelihood in the Western Border Region of England and Scotland By Allen J. Scott Solway Country: Land, Life and Livelihood in the Western Border Region of England and Scotland By Allen J. Scott This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Allen J. Scott All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6813-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6813-6 In memory of my parents William Rule Scott and Nella Maria Pieri A native son and an adopted daughter of the Solway Country TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Tables .............................................................................................. xi Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 In Search of the Solway Country Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

LOW BECKSIDE FARM Mungrisdale, Cumbria

LOW BECKSIDE FARM mungrisdale, cumbria LOW BECKSIDE FARM MUNGRISDALE, CUMBRIA, CA11 0XR highly regarded upland farm within the lake district national park Traditional farmhouse with four bedrooms Bungalow with three bedrooms Traditional stone barns Extensive modern livestock buildings Lot 1 – Low Beckside Farm set in approx. 195 acres of pasture, plus grazing rights on the common Lot 2 – 209 acres of off lying rough grazing, pasture and woodland IN ALL ABOUT 404 ACRES (163 HECTARES) For sale as a whole or in two lots A66 Trunk Road – 1.6 miles u Keswick – 9 miles u Penrith – 12 miles (All distances are approximate) Savills York Savills Carlisle River House, 17 Museum Street, York, YO1 7DJ 64 Warwick Road, [email protected] Carlisle, CA1 1DR 01904 617831 savills.co.uk Introduction Low Beckside Farm lies to the north of the A66 plantations adds to the amenity aspect of the holding. Across Mungrisdale fell and Bowscale fell. The farm has been in approximately 12 miles west of Penrith and just south of the road is a further 123 acres of permanent pasture plus valuable ELS and HLS Environmental Stewardship Schemes the hamlet of Mungrisdale. The farm has benefited from some rough grazing and woodland. one of which is rolling over on an annual basis. considerable investment in the state of the art livestock building completed in 2017 which was specifically designed Lot 2 comprises approximately 209 acres of pasture and Low Beckside Farm is likely to appeal to commercial farmers for sheep husbandry. The farm in all extends to approximately rough grazing including 29 acres of established woodland as well as lifestyle buyers seeking a manageable sized 404 acres offered for sale in two lots. -

St Nicholas News 22 31

From Fr. Gerardo StCioffari, o.p. Nicholas director of the Centro Studi Nicolaiani News 22 October 16, 2011 BASILICA PONTIFICIA DI S. NIC A communication channel to keep in touch with St Nicholas’ Friends around the world From Fr Gerardo Cioffari, o.p., 22 director of the January 21, 2012 St Nicholas Research Center in Bari TODAY JAMES ROSENTHAL PRIEST AT ST NICHOLAS AT WADE, KENT LL OUR BEST WISHES TO THE FOUNDER OF THE ST NICHOLAS’ SOCIETY AND TRUE INTERPRETER 31 OF ST NICHOLAS ’ MESSAGE Canon Jim Rosenthal, 60, who processes through the streets of Canterbury each December as the real St Nicholas, will be installed as Parish Priest at St Nicholas at Wade Church, Thanet, this Saturday (21 January). The highly successful Nicholasfest by now in its 12th year, included the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Dover walking along St Nicholas. Canon Rosenthal is the founder of the St Nicholas Society UK/USA, which attempts to teach people who Santa Claus really is, and appears in many churches and events over the Advent. Furthermore, he is a very special person also for those who are interested in the spreading of Nicholas’ cult throughout the world. In fact if you go on Internet and click for “stnicholascenter ... church Gazetteer” you will find the entire world ordained according the continents Thanks to the cooperation of Mrs Carol and the states, with a rich list of St Nicholas Myers, the Center founded by Rosenthal Churches for each country. The fact of has a very active American network, with which the Centro Studi Nicolaiani of Bari is having the image of the Church helps in continuous contact. -

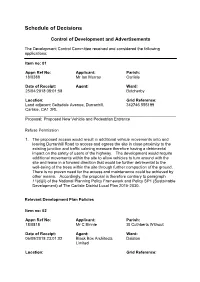

Schedule of Decisions

Schedule of Decisions Control of Development and Advertisements The Development Control Committee received and considered the following applications: Item no: 01 Appn Ref No: Applicant: Parish: 18/0388 Mr Ian Murray Carlisle Date of Receipt: Agent: Ward: 25/04/2018 08:01:58 Botcherby Location: Grid Reference: Land adjacent Geltsdale Avenue, Durranhill, 342746 555199 Carlisle, CA1 2RL Proposal: Proposed New Vehicle and Pedestrian Entrance Refuse Permission 1. The proposed access would result in additional vehicle movements onto and leaving Durranhill Road to access and egress the site in close proximity to the existing junction and traffic calming measure therefore having a detrimental impact on the safety of users of the highway. The development would require additional movements within the site to allow vehicles to turn around with the site and leave in a forward direction that would be further detrimental to the well-being of the trees within the site through further compaction of the ground. There is no proven need for the access and maintenance could be achieved by other means. Accordingly, the proposal is therefore contrary to paragraph 11(d)(ii) of the National Planning Policy Framework and Policy SP1 (Sustainable Development) of The Carlisle District Local Plan 2015-2030. Relevant Development Plan Policies Item no: 02 Appn Ref No: Applicant: Parish: 18/0818 Mr C Binnie St Cuthberts Without Date of Receipt: Agent: Ward: 06/09/2018 23:01:02 Black Box Architects Dalston Limited Location: Grid Reference: Taupin Skail, Ratten Row, Dalston, Carlisle, CA5 339415 549627 7AY Proposal: Single Storey Side And Rear Extension To Provide Kitchen And Family Room; Erection Of Replacement Garage Members resolved to give authority to the Corporate Director (Economic Development) to issue approval for the proposal subject to no adverse comments being received from any of the National Amenity Societies arising from their formal notification.