Reproductive Behavior and Vocalizations of the Bonin Petrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Metabolic Rate of Laysan Albatross and Bonin Petrel Chicks on Midway Atoll!

Pacific Science (1984), vol. 38, no. 2 © 1984 by the University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Metabolic Rate of Laysan Albatross and Bonin Petrel Chicks on Midway Atoll! 2 2 GILBERT S. GRANT ,3 AND G. CAUSEY WHiTTOW ABSTRACT: The resting metabolic rates ofLaysan albatross and Bonin petrel chicks of known age were measured on Midway Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. The mass-specific metabolism peaked at hatching and then declined to adult levels in Laysan albatross nestlings . The mass specific metabolism of hatchling Bonin petrels was similar to that of adults, but it tripled shortly after hatching. Fasting and feeding episodes affected day-to-day changes in petrel chick metabolism. THE RESTING METABOLIC RATES of chicks rep METHODS resent the major part of their energy expen diture, as they do not fly and their level of The metabolic rates of Laysan albatross activity .is generally low (Blem 1978). The chicks ofknown age on Sand Island, Midway metabolic rate increases as the chick grows Atoll (28°13' N, 177°23' W) were measured in but the relationship between metabolic rate a building immediately adjacent to the nesting and body mass var ies during growth, the par sites. The chicks were placed in a small plexi ticular pattern of variation depending on a glas chamber or in an air-tight wooden box number of factors (Ricklefs 1974). In the (0.7 m on all sides), depending on the size of Procellariiformes, which have relatively long the chick. In the latter instance, a plexiglas nestling periods, the metabolic rate of grow cover allowed observation during a series of ing chicks is known only for Leach's storm measurements. -

The Role of Seabirds in Hawaiian Subsistence: Implications for Interpreting Avian Extinction and Extirpation in Polynesia

The Role of Seabirds in Hawaiian Subsistence: Implications for Interpreting Avian Extinction and Extirpation in Polynesia JADELYN J. MONIZ SCIENTISTS ESTIMATE THAT ABOUT ONE-FIFTH of the species of birds that existed in the world a few thousand years ago has disappeared as a result of human activ ities (Diamond 1989). Subfossil and archaeological evidence suggests that before human occupation was established, the native fauna throughout Polynesia was taxonomically more diverse than historical documents reflect (James 1983; James et al. 1987; Kirch 1982; Olson and James 1982,1984,1991; Steadman 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993). Archaeologists have documented extinct avian species in western Polynesia and throughout eastern Polynesia including Pitcairn Island and the islands of the Marquesas, the Societies, the Cooks, and Hawai'i (Steadman 1989, 1991,1992,1993). Today, researchers commonly refer to the state of Hawai'i as "the endangered species capital of the nation" (National Geographic, September 1995). The Hawai ian Islands lay claim to nearly one-third of all the species listed on the endangered and threatened species list in the United States. Hawaiian taxa account for nearly three-quarters of the nation's extinct species. This count includes plants, land snails, insects, birds, and other organisms. Recent subfossil discoveries have added to the number of known endemic bird species that once inhabited these islands. In 1926 scientists found the first avian subfossil species on the island of Hawai'i in a tunnel under 75 feet of lava (Wetmore 1943). Wetmore identified this spe cies as Geochen rhuax, a member of the goose family, Anatidae. It was larger than the only known living goose in the Hawaiian Islands, the Nene. -

Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics of Bulwer's Petrels, Bulweria Bulwerii, on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands!

Pacific Science, vol. 54, no. 2: 183-188 © 2000 by University of Hawai'i Press. All rights reserved Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics of Bulwer's Petrels, Bulweria bulwerii, on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands! 2 3 2 G. C. WmTTow • AND T. N. PETrn ABSTRACT: Measured values for Bulwer's Petrel eggs and eggshells from Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, were within 10% of predicted values available in the literature. In the absence of published predictive equa tions for egg volume, fresh-egg contents, and total functional pore area of the shell, in Procellariiformes, new logarithmic relationships were developed for tropical Procellariiformes. Data are now needed for species breeding at higher latitudes to determine if these relationships are representative of all Procellarii formes. BULWER'S PETREL IS a small, procellariiform placing the air ill the aircell with distilled seabird of the tropical Atlantic, Pacific, and water (Grant et al. 1982a). Egg volumes were Indian Oceans (Warham 1990, Megyesi and measured by weighing the eggs in air and in O'Daniel 1997). In the Hawaiian Archipel water (Rahn et al. 1976). Shell weight and ago, it breeds on islands from Pearl and shell thickness were determined on shells that Hermes Reef in the Northwestern Hawaiian had been dried in a desiccator for at least 3 Islands, to offshore islands of Hawai'i in the days. Shell weight was measured by weighing main Hawaiian Islands (Harrison 1990). the dried shells on a Mettler balance (Model Previously, data were presented for, inter H6) to the nearest 0.1 mg. Shell thickness was alia, the incubation period and the incuba determined with micrometer calipers (Starrett tion weight loss of eggs on Manana, a small No. -

Midway Seabird Protection Plan Story

Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. Midway Seabird Protection Plan – Draft Environmental Assessment Learn About the Emerging Threat Welcome to Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. Midway Atoll is 1,200 miles northwest of Honolulu near the end of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. It is inside one of the largest protected areas in the world. This tiny atoll is home to over 3 million seabirds. And the world's largest colonies of Laysan and Black-footed albatross. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. But in 2015, a new threat emerged. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. Warning: Some of the following content is disturbing and contains images of dead and wounded albatross. Link to Video with Matt Brown Mice were attacking adult albatross as they sat on their nests - essentially eating the birds alive. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Climate Change and Seabirds of the California Current and Pacific Islands Ecosystems: Observed and Potential Impacts and Management Implications

Climate Change and Seabirds of the California Current and Pacific Islands Ecosystems: Observed and Potential Impacts and Management Implications Final Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1 Lindsay Young Pacific Rim Conservation Honolulu, Hawaii Robert M. Suryan Oregon State University Newport, Oregon David Duffy University of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii William J. Sydeman Farallon Institute Petaluma, California 3 May 2012 1 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Climate Change and Seabirds ................................................................................................................... 6 Geographic Scope ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Natural Climate Variability and North Pacific Ecosystems........................................................................ 8 The California Current ................................................................................................................................... 9 Climate Change factors ........................................................................................................................... 10 Atmospheric circulation ..................................................................................................................... -

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, and CONSERVATION of the SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides Georgicus) in NEW ZEALAND

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, AND CONSERVATION OF THE SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides georgicus) IN NEW ZEALAND BY JOHANNES HARTMUT FISCHER A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology School of Biological Sciences Faculty of Sciences Victoria University of Wellington September 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Heiko U. Wittmer, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington. © Johannes Hartmut Fischer. September 2016. Ecology, Taxonomic Status and Conservation of the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus) in New Zealand. ABSTRACT ROCELLARIFORMES IS A diverse order of seabirds under considerable pressure P from onshore and offshore threats. New Zealand hosts a large and diverse community of Procellariiformes, but many species are at risk of extinction. In this thesis, I aim to provide an overview of threats and conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes in general, and an assessment of the remaining terrestrial threats to the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus; SGDP), a Nationally Critical Procellariiform species restricted to Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), post invasive species eradication efforts in particular. I reviewed 145 references and assessed 14 current threats and 13 conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes (n = 48) in a meta-analysis. I then assessed the terrestrial threats to the SGDP by analysing the influence of five physical, three competition, and three plant variables on nest-site selection using an information theoretic approach. Furthermore, I assessed the impacts of interspecific interactions at 20 SGDP burrows using remote cameras. Finally, to address species limits within the SGDP complex, I measured phenotypic differences (10 biometric and eight plumage characters) in 80 live birds and 53 study skins, as conservation prioritisation relies on accurate taxonomic classification. -

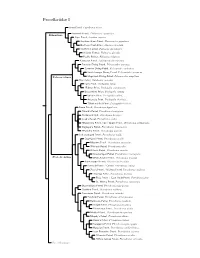

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Breeding Biology of Tristram's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma Tristrami at French Frigate Shoals and Laysan Island, Northwest Hawaii

McClelland et al.: Tristram’s Storm-Petrel breeding biology 175 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF TRISTRAM’S STORM-PETREL OCEANODROMA TRISTRAMI AT FRENCH FRIGATE SHOALS AND LAYSAN ISLAND, NORTHWEST HAWAIIAN ISLANDS GREGORY T.W. McCLELLAND,1,2 IAN L. JONES,1 JENNIFER L. LAVERS1,3 & FUMIO SATO4 1Department of Biology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland, A1B 3X9, Canada 2Current address: Center for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa ([email protected]) 3Current address: Department of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001, Australia 4Bird Migration Research Center, Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, Konoyama, Abiko, Chiba, 270-1145, Japan Received 2 September 2007, accepted 1 October 2008 SUMMARY MCCLELLAND, G.T.W., JONES, I.L., LAVERS, J.L. & SATO, F. 2008. Breeding biology of Tristram’s Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma tristrami at French Frigate Shoals and Laysan Island, Northwest Hawaiian Islands. Marine Ornithology 36: 175–181. We investigated Tristram’s Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma tristrami on Laysan Island and French Frigate Shoals, Northwest Hawaiian Islands, in the first detailed study of this species’ breeding biology. Breeding extended through the boreal winter from mid-October to mid-June. The mean hatching success on Laysan Island was 0.35 in 2004 and 0.46 in 2005; on Tern Island, it was 0.53 in 2005 and 0.61 in 2006. Fledging success was 0.45, and breeding success 0.16 at Laysan in 2004. At Tern Island, mean fledging success during 2005–2008 was 0.48 (range: 0.47 to 0.51) and overall breeding success in 2005 and 2006 was 0.27 and 0.28 respectively.