Special Report on Pandemic Readiness and Response in Long-Term Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Reporting and Is Ultimately Responsible for Reviewing and Approving the Financial Statements

Treasury Board Secretariat ANNUAL REPORT OF ONTARIO Financial Statements of Government Organizations VOLUME 2B | 2015-2016 7$%/( 2)&217(176 9ROXPH% 3DJH *HQHUDO 5HVSRQVLEOH0LQLVWU\IRU*RYHUQPHQW$JHQFLHV LL $*XLGHWRWKHAnnual Report .. LY ),1$1&,$/ 67$7(0(176 6HFWLRQ ņ*RYHUQPHQW 2UJDQL]DWLRQV± &RQW¶G 1LDJDUD3DUNV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 1RUWKHUQ2QWDULR+HULWDJH)XQG&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR$JHQF\IRU+HDOWK 3URWHFWLRQDQG 3URPRWLRQ 3XEOLF+HDOWK2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR&DSLWDO*URZWK&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR&OHDQ :DWHU$JHQF\ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 79 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR(OHFWULFLW\)LQDQFLDO&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR(QHUJ\%RDUG 0DUFK 2QWDULR)LQDQFLQJ$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR)UHQFK/DQJXDJH(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,PPLJUDQW,QYHVWRU&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,QIUDVWUXFWXUH DQG/DQGV&RUSRUDWLRQ ,QIUDVWUXFWXUH 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR0RUWJDJH DQG+RXVLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR1RUWKODQG7UDQVSRUWDWLRQ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR3ODFH&RUSRUDWLRQ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR5DFLQJ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR6HFXULWLHV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7RXULVP0DUNHWLQJ3DUWQHUVKLS&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7ULOOLXP)RXQGDWLRQ 0DUFK 2UQJH 0DUFK 2WWDZD&RQYHQWLRQ&HQWUH &RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 3URYLQFH RI2QWDULR&RXQFLOIRUWKH$UWV 2QWDULR$UWV&RXQFLO 0DUFK 7KH 5R\DO2QWDULR0XVHXP 0DUFK 7RURQWR 2UJDQL]LQJ&RPPLWWHHIRUWKH 3DQ $PHULFDQ DQG3DUDSDQ$PHULFDQ*DPHV 7RURQWR 0DUFK 7RURQWR :DWHUIURQW5HYLWDOL]DWLRQ&RUSRUDWLRQ :DWHUIURQW7RURQWR 0DUFK L ANNUAL REPORT 5(63216,%/(0,1,675<)25*29(510(17%86,1(66(17(535,6(6 25*$1,=$7,216758676 0,6&(//$1(286),1$1&,$/67$7(0(176 -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY 2013 STATISTICS In free and open societies, governments must be accessible and transparent to their citizens. TABLE OF CONTENTS Requests by the Public ...................................... 1 Provincial Compliance ..................................... 3 Municipal Compliance ................................... 12 Appeals .............................................................. 26 Privacy Complaints .......................................... 38 Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) .................................. 41 As I look back on the past years of the IPC, I feel that Ontarians can be assured that this office has grown into a first-class agency, known around the world for demonstrating innovation and leadership, in the fields of both access and privacy. STATISTICS 4 1 REQUESTS BY THE PUBLIC UNDER FIPPA/MFIPPA There were 55,760 freedom of information (FOI) requests filed across Ontario in 2013, nearly a 6% increase over 2012 where 52,831 were filed TOTAL FOI REQUESTS FILED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,995 17,334 34,329 Provincial 7,029 14,402 21,431 Total 24,024 31,736 55,760 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,726 17,304 34,030 Provincial 6,825 13,996 20,821 Total 23,551 31,300 54,851 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY SOURCE AND JURISDICTION Municipal Provincial Total -

Master's Research Paper Officers of the Assembly and the Ontario

Master's Research Paper Officers of the Assembly and the Ontario Legislature: Reconsidering the Relationship Jocelyn McCauley Student Number: 216280703 Dr. Peter P. Constantinou A Master's Research Paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Policy, Administration and Law York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada July 2020 Abstract Officers of Parliament, or as they are referred to in Ontario, “officers of the Assembly”, have emerged within Westminster systems as a recognized tool for enhancing parliamentary oversight and increasing transparency in government. However, in Ontario, the absence of a clearly defined relationship with the provincial legislature has meant that certain officers of the Assembly have felt it necessary to “lobby” individual members and committees, as well as the media, in order to carry out their accountability and oversight functions. This lack of clarity places unnecessary stress on the relationship between independent officers, the Ontario Legislature, and the public sector, and can also negatively impact the public’s perception of government overall. This paper looks specifically at the relationship between the Ontario Legislature and officers of the Assembly, in terms of their governance structures, their appearances in legislative committees, and references to their work in House and committee proceedings. It finds that reforms are needed in order to strengthen officers’ relationships with the Legislature. Independent officers possess few powers of enforcement and as such, strong ties to the Assembly are necessary to ensure that recommended action is taken by legislators defend public trust and dollars. 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. -

Redesigning Care Through Digital Health Implementation

Redesigning Care through Digital Health Implementation Lessons Learned from Ontario Hospitals Acknowledgements The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) would like to thank all the member hospitals and provincial partners who contributed to this resource. Individual contributing authors are noted at the end of each story. The OHA also acknowledges the ongoing and valuable work of all health care professionals who embrace change as hospitals innovate to improve care delivery and patient experiences. Disclaimer This publication is a collection of hospital submissions The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) assumes no showcasing digital health implementation initiatives responsibility or liability for any harm, damage or other across the province. It has been created for general losses, direct or indirect, resulting from any reliance on information purposes only and implementation the use or the misuse of any information contained in suggestions should be adapted to the circumstances of this resource. Facts, figures and resources mentioned each hospital. Hospitals should seek their own legal and/ throughout the document have not been validated by or professional advice and opinion when developing the OHA. For details on sources of information, readers their organization’s approach and plans for digital health are encouraged to contact the hospital directly using the implementation. contact information cited in each submission. I Introduction Digital technologies have, and will continue to, These factors point to what may be the key ingredient -

Joint Submission the Standing Committee on General Government Re: Bill 8, Public Sector and MPP Accountability and Transparen

Joint Submission to The Standing Committee on General Government Re: Bill 8, Public Sector and MPP Accountability and Transparency Act, 2014 November 26, 2014 November 26, 2014 To: The Standing Committee on General Government Re: Bill 8, Public Sector and MPP Accountability and Transparency Act, 2014 The four school board/trustee associations would like to take the opportunity to respond and comment on this omnibus piece of legislation and in particular two schedules, out of the total eleven schedules, that will directly affect our membership. The bill’s title refers to accountability and transparency– two values that school boards and their elected trustees strive to ensure on a daily basis. Governed by the Education Act, school boards operate under many regulations, policies and guidelines and provide numerous reports, as required by the Ministry of Education, in order to demonstrate transparency and accountability measures. While we believe the government’s intention is to increase public confidence and to show an openness to the province’s electorate, we feel that, without due consideration of the current mechanisms for accountability and transparency that apply to school boards, we have been unfairly captured in the consideration of Schedule 1 – Broader Public Sector Executive Compensation Act, 2014 and Schedule 9 – Amendments to the Ombudsman Act and Related Amendments. The reporting requirements for school boards far exceed requirements in any other sector. These include highly detailed financial reporting three times a year in addition to multiple layers of reporting with regard to students, employees and board improvement planning. Schedule 1: Broader Public Sector Executive Compensation Act, 2014 The new proposed legislation aims to establish compensation frameworks for a lengthy list of public sector employers including those at Ornge, Metrolinx, OLG and the LCBO as well as the executives at school boards. -

ITAC Health PHIPA Modernization Feedback to ONTARIO MOHLTC FEBRUARY 21, 2020 Summary 2

ITAC Health PHIPA Modernization Feedback TO ONTARIO MOHLTC FEBRUARY 21, 2020 Summary 2 At the conclusion of November 20, 2019 meeting hosted by the MOHLTC privacy policy team that included representatives from ITAC Health Board and members, an action opportunity was requested and permission received to share the Ministry’s PHIPA Modernization document with select privacy subject matter experts within the ITAC Health membership. ITAC Health members, including SME members, have provided input that has been collected and summarized in this document. Our goal is to provide timely and in-depth feedback beyond the November meeting’s initial reflections on the PHIPA Modernization policies. We appreciate the opportunity to contribute to the Ministry our summary that includes five sections in companion to this executive summary: thematic topics related to PHIPA Modernization; beyond PHIPA, privacy (and security) contextual discussion; and general comments, recommendations and questions on PHIPA Modernization; direct references to slide content in Ministry’s PHIPHA Modernization deck; bibliography of external documents relevant to PHIPA Modernization effort 1. PHIPA Privacy Themes 3 Roles and responsibilities under the new PHIPA Penalties Under the New PHIPA Consent – aligned with GDPR Patient access to information De-identification and secondary use Right to portability Right to be forgotten Breach notification Research Ethic Boards harmonization Governance operating model Levers for change to enable data sharing Roles and responsibilities under the 4 new PHIPA Patient - a natural person whose personal data is processed by a controller or processor Health information custodian (HIC) - a person who determines the purposes for which and the manner in which any personal data are, or are to be, processed. -

EAPO Webinar Series : Rights of Older Adults

EAPO Webinar Series : Rights of Older Adults March 31st, 2020 The information and opinions expressed here today are not necessarily those of the Government of Ontario Welcome All attendees will be muted during the webinar. Recording: Webinar will be recorded and posted on EAPO’s and/or partner organization’s website. ASL Interpreter: Video of Interpreter will be visible during the webinar today and name of ASL Interpreter is under picture. ASL Interpreting provided by Adjusting Video Size: Drag the line between the video frame and slides to the left (adjust at beginning of the webinar). Welcome to our Webinar! Speaker: Will be visible while presenting. Once the presentation is completed, all speakers will be visible for the Question/Answer period. Questions or Issues: Participants can type their questions in Question/Answer box. A response will be posted during the webinar or asked to speaker after the presentation. The Chat box can also be used to post comments during the session. Evaluation: After the session, you will see pop-up screen asking you to provide your feedback and suggestions for future webinars. Contact information will be provide at the end of presentation. Land Acknowledgement MISSION EAPO envisions an Ontario where ALL seniors are free from abuse, have a strong voice, feel safe and respected. ACTION Raising awareness, delivering education and training, working collaboratively with like-minded organizations and assisting with service coordination and advocacy. @EAPreventionON #RestoringRespect STOP ABUSE – RESTORE RESPECT SIMPLY PUT, WE ALL HAVE A ROLE TO PLAY EAPO is mandated to support the implementation of Ontario’s Strategy to Combat Elder Abuse. -

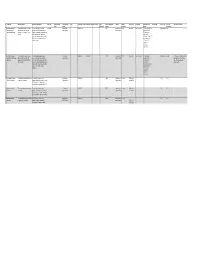

Copy of Data Inventory

Copy of Data Inventory # Public Title Short Description Long Description (Body) Other Title Data Custodian Data Custodian Tags Date Range ‐ Start Date Range ‐ End Date Created Date Contains Geographic Publisher Update Access Level Exemption Rationale not to Dataset URL License Type File Types Additional Comments Email Branch published Markers Frequency Release (extensions) 1 Consent and Capacity This dataset contains case‐related The case management system CaseLoad Consent and 2014‐03‐15 TRUE Consent and Daily Restricted Confidentiality The case management Other Licence DBF Board (CCB) Case data and information for CCB provides case‐related data such as Capacity Board Capacity Board system contains Management System applications from March 15 2014 contact information of the parties that private contact onward. come before the CCB, information information, about the hearing scheduling process, reference to personal file status, hearing information and health information case disposition. and sensitive, confidential party/case information. 2 Consent and Capacity This dataset contains case‐related The scheduling database provides Consent and 2006‐04‐01 2014‐03‐14 TRUE Consent and Other Restricted Confidentiality The scheduling Other Licence ACCDB This dataset is no longer updated. Board (CCB) Scheduling data and information for CCB case‐related data such as contact Capacity Board Capacity Board database contains Data not used for day‐to‐day Database applications from April 1 2006 to information of the parties that come private contact business. Occasional use for March 14 2014. before the CCB, information about the information, reference only. hearing scheduling process, file status, reference to personal hearing information and case health information disposition. and sensitive, confidential party/case information. -

Dementia Care During a Healthcare Crisis

Dementia Care during a Healthcare Crisis By Aneesha Kotti Presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Design in Strategic Foresight and Innovation. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2021 CREATIVE COMMONS COPYRIGHT NOTICE This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • Non-Commercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. • Share Alike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. Notices - You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation. No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material. -

Ontario's Electronic Health Record (EHR

Ontario’s Electronic Health Record (EHR) Conceptual Information Model (CIM) Digital Health Enabled VERSION 2.0 Version History Version Number Date Summary of Change Changed By 1.0 November 2014 Initial version part of Ontario’s Ehealth Blueprint eHealth Ontario, Architecture & Standards Division 2.0 June 26, 2019 Updated to align with HL7 Electronic Health Record eHealth Ontario, Architecture & System Functional Model (EHR-S FM) [Draft Standards Division Release 2.1] CIM 2.0 Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Information Architecture .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 EHR Information Principles ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Modelling References .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Conceptual Information -

Oversight Enhanced”

“Oversight Enhanced” Submission to the Standing Committee on Justice Policy regarding Bill 175, Safer Ontario Act, 2017 Paul Dubé Ombudsman of Ontario February 2018 Table of Contents Reinforcing Police Oversight ........................................................................................... 3 The Ontario Ombudsman and Police Oversight .............................................................. 4 Ontario’s three police oversight bodies ........................................................................ 4 Ombudsman oversight of the SIU, OIPRD, and OCPC ............................................... 5 Oversight Unseen and Oversight Undermined ............................................................. 5 Submission to the Independent Police Oversight Review ............................................ 6 Bill 175: A New Era for Police Accountability .................................................................. 7 Remaining gaps in Bill 175........................................................................................... 8 Ensuring civilian representation ................................................................................ 8 Ensuring effective Ombudsman oversight .............................................................. 11 Ensuring an effective Ontario Special Investigations Unit ....................................... 13 De-escalation training – a key missing piece .......................................................... 14 Conclusion ................................................................................................................... -

1/2 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Patient Ombudsman Launches Systemic Investigation Into the Resident and Caregiver Experience at Ontar

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Patient Ombudsman launches systemic investigation into the resident and caregiver experience at Ontario’s Long-term Care Homes with outbreaks of COVID-19 (Toronto, June 2nd, 2020) Patient Ombudsman began monitoring the impact of COVID-19 on the experiences of patients, residents and caregivers when the pandemic was first declared. Complaints from residents, family members and whistleblowers pointed to a crisis in Ontario’s long-term care homes. On April 26th, 2020, Patient Ombudsman launched a public appeal for COVID-19 complaints in long-term care. Patient Ombudsman asked staff, family members, caregivers and residents to disclose situations where they felt the safety of residents and staff may be in significant jeopardy. Since March, Patient Ombudsman received 150 complaints about long-term care homes. That number continues to grow. “Our office would like to thank every resident, caregiver and staff person of a long-term care home for having the courage to come forward with their complaints. We are committed to resolving these complaints and amplifying the voices of residents and caregivers as we learn from their experiences. Patient Ombudsman acknowledges Ontario Ombudsman’s separate investigation of the oversight of the long-term care system by the province’s Ministry of Long-Term Care and Ministry of Health. Our investigation is specific to the resident and caregiver experience at long-term care homes with outbreaks of COVID-19. We feel that this investigation will help long-term care homes prepare for future outbreaks of infectious diseases, including COVID-19.” (Craig Thompson, Executive Director, Patient Ombudsman) Investigation focus The investigation will focus on the experience of residents and caregivers in those long-term care homes that experienced an outbreak of COVID-19.