Segmental Speckled Lentiginous Nevus Exacerbated by Pregnancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melanocytes and Their Diseases

Downloaded from http://perspectivesinmedicine.cshlp.org/ on October 2, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Melanocytes and Their Diseases Yuji Yamaguchi1 and Vincent J. Hearing2 1Medical, AbbVie GK, Mita, Tokyo 108-6302, Japan 2Laboratory of Cell Biology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 Correspondence: [email protected] Human melanocytes are distributed not only in the epidermis and in hair follicles but also in mucosa, cochlea (ear), iris (eye), and mesencephalon (brain) among other tissues. Melano- cytes, which are derived from the neural crest, are unique in that they produce eu-/pheo- melanin pigments in unique membrane-bound organelles termed melanosomes, which can be divided into four stages depending on their degree of maturation. Pigmentation production is determined by three distinct elements: enzymes involved in melanin synthesis, proteins required for melanosome structure, and proteins required for their trafficking and distribution. Many genes are involved in regulating pigmentation at various levels, and mutations in many of them cause pigmentary disorders, which can be classified into three types: hyperpigmen- tation (including melasma), hypopigmentation (including oculocutaneous albinism [OCA]), and mixed hyper-/hypopigmentation (including dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria). We briefly review vitiligo as a representative of an acquired hypopigmentation disorder. igments that determine human skin colors somes can be divided into four stages depend- Pinclude melanin, hemoglobin (red), hemo- ing on their degree of maturation. Early mela- siderin (brown), carotene (yellow), and bilin nosomes, especially stage I melanosomes, are (yellow). Among those, melanins play key roles similar to lysosomes whereas late melanosomes in determining human skin (and hair) pigmen- contain a structured matrix and highly dense tation. -

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

Acral Compound Nevus SJ Yun S Korea

University of Pennsylvania, Founded by Ben Franklin in 1740 Disclosures Consultant for Myriad Genetics and for SciBase (might try to sell you a book, as well) Multidimensional Pathway Classification of Melanocytic Tumors WHO 4th Edition, 2018 Epidemiologic, Clinical, Histologic and Genomic Aspects of Melanoma David E. Elder, MB ChB, FRCPA University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Napa, May, 2018 3rd Edition, 2006 Malignant Melanoma • A malignant tumor of melanocytes • Not all melanomas are the same – variation in: – Epidemiology – risk factors, populations – Cell/Site of origin – Precursors – Clinical morphology – Microscopic morphology – Simulants – Genomic abnormalities Incidence of Melanoma D.M. Parkin et al. CSD/Site-Related Classification • Bastian’s CSD/Site-Related Classification (Taxonomy) of Melanoma – “The guiding principles for distinguishing taxa are genetic alterations that arise early during progression; clinical or histologic features of the primary tumor; characteristics of the host, such as age of onset, ethnicity, and skin type; and the role of environmental factors such as UV radiation.” Bastian 2015 Epithelium associated Site High UV Low UV Glabrous Mucosa Benign Acquired Spitz nevus nevus Atypical Dysplastic Spitz Borderline nevus tumor High Desmopl. Low-CSD Spitzoid Acral Mucosal Malignant CSD melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma 105 Point mutations 103 Structural Rearrangements 2018 WHO Classification of Melanoma • Integrates Epidemiologic, Genomic, Clinical and Histopathologic Features • Assists -

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

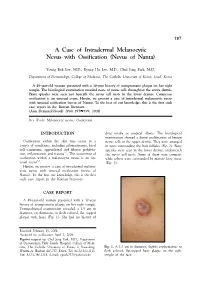

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Two Cases of Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome in One Family

221 Two Cases of Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome in One Family Dong Jin Ryu, M.D., Yeon Sook Kwon, M.D., Mi Ryung Roh, M.D., Min-Geol Lee, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Biology Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, or Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal dominant multiple system disorder with high penetrance and variable expressions, although it can also arise spontaneously. The diagnostic criteria for nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome include multiple basal cell carcinomas, palmoplantar pits, multiple odontogenic keratocysts, skeletal anomalies, positive family history, ectopic calcification and neurological anomalies. We report a brother and sister who were both diagnosed with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 221∼225, 2008) Key Words: Basal cell carcinoma, Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, Odontogenic keratocyst INTRODUCTION cell carcinoma syndrome. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), or Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an auto- CASE REPORT somal dominant multiple system disorder with high 1 penetrance and variable expressions . However, Case 1 60% of patients with NBCCS are sporadic cases. It An 11-year-old male was referred to our depart- has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 60,000 with ment for the evaluation of multiple miliary sized 2 equal distributions among males and females . The pigmented macules on the palm and sole that had well-defined diagnostic criteria include cutaneous increased in number over several years. He had an anomalies, dento-facial anomalies, skeletal ano- operation for inguinal hernia at 3 years of age, but malies, positive family history, neurological ano- no other medical problems. -

Nevus Spilus: Is the Presence of Hair Associated with an Increased Risk for Melanoma?

Nevus Spilus: Is the Presence of Hair Associated With an Increased Risk for Melanoma? Robert Milton Gathings, MD; Raveena Reddy, MD; Ashish C. Bhatia, MD; Robert T. Brodell, MD PRACTICE POINTS • Nevus spilus (NS) appears as a café au lait macule studded with darker brown “moles.” • Although melanoma has been described in NS, it is rare. • There is no evidence that hairy NS are predisposed to melanoma. copy not Nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled len- he term nevus spilus (NS), also known as tiginous nevus, is characterized by background speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperpla- Tin the 19th century to describe lesions with sia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci.Do background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic Nevus spilus occurs in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker population worldwide. Reports of melanoma aris- foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, ing within hypertrichotic NS suggest that hyper- compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and trichosis may be a marker for the development of more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and melanoma. We present a case of a hypertrichotic papular subtypes have been described.1 This birth- NS without melanoma and also provide a review of mark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% previously reported cases of hypertrichosis in NS. of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis We believe that NS has aCUTIS lower risk for malignant has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases degeneration than congenital melanocytic nevi of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that (CMN) of the same size, and it is unlikely that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant hypertrichosis is a marker for melanoma in NS. -

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–Like Macules (Hori's Nevus): a Case

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–like Macules (Hori’s Nevus): A Case Report and Treatment Update Jamie Hale, DO,* David Dorton, DO,** Kaisa van der Kooi, MD*** *Dermatology Resident, 2nd year, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL **Dermatologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL ***Dermatopathologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL Abstract This is a case of a 71-year-old African American female who presented with bilateral periorbital hyperpigmentation. After failing treatment with a topical retinoid and hydroquinone, a biopsy was performed and was consistent with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules, or Hori’s nevus. A review of histopathology, etiology, and treatment is discussed below. cream and tretinoin 0.05% gel. At this visit, a Introduction Figure 2 Acquired nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM), punch biopsy of her left zygoma was performed. or Hori’s nevus, clinically presents as bilateral, Histopathology reported sparse proliferation blue-gray to gray-brown macules of the zygomatic of irregularly shaped, haphazardly arranged melanocytes extending from the superficial area. It less often presents on the forehead, upper reticular dermis to mid-deep reticular dermis outer eyelids, and nose.1 It is most common in women of Asian descent and has been reported Figure 4 in ages 20 to 70. Classically, the eye and oral mucosa are uninvolved. This condition is commonly misdiagnosed as melasma.1 The etiology of this condition is not fully understood, and therefore no standardized treatment has been Figure 3 established. Case Report A 71-year-old African American female initially presented with a two week history of a pruritic, flaky rash with discoloration of her face. -

Co-Occurrence of Vitiligo and Becker's Nevus: a Case Report

Case Report Olgu Sunumu DOI: 10.4274/turkderm.71354 Turkderm - Arch Turk Dermatol Venerology 2016;50 Co-occurrence of vitiligo and Becker's nevus: A case report Vitiligo ve Becker nevüs birlikteliği: Olgu sunumu Ayşegül Yalçınkaya İyidal, Özge Çokbankir*, Arzu Kılıç** Ağrı State Hospital, Clinic of Dermatology, *Clinic of Pathology, Ağrı, Turkey **Balıkesir University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Dermatology, Balıkesir, Turkey Abstract Vitiligo is an acquired disorder with an unknown etiology in which genetic and non-genetic factors coexist. Melanocytes are destructed in the affected skin areas and clinically depigmented macules and patches appear on the skin. Becker's nevus (BN) appears as hyperpigmented macule, patch or verrucous plaques with sharp and irregular margins and often unilateral occurrence and with associated hypertrichosis in various degrees. Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it is suggested to represent a hamartomatous lesion harboring androgen receptors on the lesion. In this report, we present a 19-year-old male patient who developed vitiligo lesions and then BN adjacent to the vitiligo lesion in the right upper back portion of the body ten years after the initial vitiligo lesion. Keywords: Becker's nevus, vitiligo, co-occurrence Öz Vitiligo nedeni tam olarak bilinmeyen, genetik ve genetik olmayan faktörlerin birlikte rol oynadığı edinsel bir bozukluktur. Bu hastalıkta tutulan deride melanositler ortadan kalkar, klinik olarak depigmente makül ve yamalar belirir. Becker nevüs (BN) sıklıkla unilateral dağılım gösteren, keskin ama düzensiz sınırlı hiperpigmente makül, yama veya verrüköz plakların izlendiği, üzerinde değişik derecelerde hipertrikozun bulunduğu bir hastalıktır. Patogenezi belli olmamakla birlikte hamartamatöz bir lezyon olduğu ve üzerinde androjen reseptörlerinin arttığı ileri sürülmektedir. -

Phacomatosis Spilorosea Versus Phacomatosis Melanorosea

Acta Dermatovenerologica 2021;30:27-30 Acta Dermatovenerol APA Alpina, Pannonica et Adriatica doi: 10.15570/actaapa.2021.6 Phacomatosis spilorosea versus phacomatosis melanorosea: a critical reappraisal of the worldwide literature with updated classification of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis Daniele Torchia1 ✉ 1Department of Dermatology, James Paget University Hospital, Gorleston-on-Sea, United Kingdom. Abstract Introduction: Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is a term encompassing a group of disorders characterized by the coexistence of a segmental pigmented nevus of melanocytic origin and segmental capillary nevus. Over the past decades, confusion over the names and definitions of phacomatosis spilorosea, phacomatosis melanorosea, and their defining nevi, as well as of unclassifi- able phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cases, has led to several misplaced diagnoses in published cases. Methods: A systematic and critical review of the worldwide literature on phacomatosis spilorosea and phacomatosis melanorosea was carried out. Results: This study yielded 18 definite instances of phacomatosis spilorosea and 14 of phacomatosis melanorosea, with one and six previously unrecognized cases, respectively. Conclusions: Phacomatosis spilorosea predominantly involves the musculoskeletal system and can be complicated by neuro- logical manifestations. Phacomatosis melanorosea is sometimes associated with ancillary cutaneous lesions, displays a relevant association with vascular malformations of the brain, and in general appears to be a less severe syndrome. -

Optimal Management of Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi (Moles): Current Perspectives

Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives Kabir Sardana Abstract: Although common acquired melanocytic nevi are largely benign, they are probably Payal Chakravarty one of the most common indications for cosmetic surgery encountered by dermatologists. With Khushbu Goel recent advances, noninvasive tools can largely determine the potential for malignancy, although they cannot supplant histology. Although surgical shave excision with its myriad modifications Department of Dermatology and STD, Maulana Azad Medical College and has been in vogue for decades, the lack of an adequate histological sample, the largely blind Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, Delhi, nature of the procedure, and the possibility of recurrence are persisting issues. Pigment-specific India lasers were initially used in the Q-switched mode, which was based on the thermal relaxation time of the melanocyte (size 7 µm; 1 µsec), which is not the primary target in melanocytic nevus. The cluster of nevus cells (100 µm) probably lends itself to treatment with a millisecond laser rather than a nanosecond laser. Thus, normal mode pigment-specific lasers and pulsed ablative lasers (CO2/erbium [Er]:yttrium aluminum garnet [YAG]) are more suited to treat acquired melanocytic nevi. The complexities of treating this disorder can be overcome by following a structured approach by using lasers that achieve the appropriate depth to treat the three subtypes of nevi: junctional, compound, and dermal. Thus, junctional nevi respond to Q-switched/normal mode pigment lasers, where for the compound and dermal nevi, pulsed ablative laser (CO2/ Er:YAG) may be needed. -

Dermoscopy on Nevus Comedonicus: a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Case report Dermoscopy on nevus comedonicus: a case report and review of the literature Grażyna Kamińska-Winciorek 1, Radosław Śpiewak 2 1The Center for Cancer Prevention and Treatment, Katowice, Poland Head: Beata Wydmańska 2Department of Experimental Dermatology and Cosmetology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland Head: Prof. Radosław Śpiewak MD. PhD Postep Derm Alergol 2013; XXX, 4: 252 –254 DOI: 10.5114/pdia.2013.37036 Abstract Nevus comedonicus (NC) is a very rare, benign hamartoma characterised by the occurrence of dilated, comedo-like openings, typically on the face, neck, upper arms, chest or abdomen. In uncertain cases, histopathological exami - nation confirms the diagnosis. The authors suggest dermoscopy as a rapid and useful method of initial diagnosis of nevus comedonicus based upon its distinctive dermoscopic features. The dermoscopy reveals numerous light- and dark-brown, circular or barrel-shaped, homogenous areas with prominent keratin plugs. Key words: dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, nevus comedonicus, epidermal nevus, acne vulgaris. Introduction a hypopigmented, slightly hypotrophic, linear spot of Nevus comedonicus (NC) is a benign hamartoma cha - 2 cm × 8 cm (Figure 1). The plugs could not be extracted racterised by the occurrence of dilated comedo-like open - mechanically. The dermoscopic examination revealed ings, with black or brown keratin plugs, typically localised the distinctive pattern consisting of dark, sharply demar - on the face, neck, upper arms, chest or abdomen. The diag - cated keratin plugs of 1–3 mm diameter, numerous struc - nosis of nevus comedonicus is relatively easy. In uncertain tureless, circular- and barrel-shaped, homogenous areas cases, a typical histopathological picture confirms the diag - with hyperkeratotic plugs of various shades of brown nosis.