Post-Conflict Transitions: National Experience and International Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security Council Distr

UNITED NATIONS S Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/1998/720 5 August 1998 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 5 AUGUST 1998 FROM THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF ERITREA TO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to transmit to you a press statement issued today, 5 August 1998, by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State of Eritrea concerning the meeting of the Ministerial Committee of the Organization of African Unity on the Eritrea-Ethiopia conflict, held from 1 to 2 August (see annex). I should be grateful if you would kindly circulate this letter and its annex as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Haile MENKERIOS Ambassador Permanent Representative 98-22901 (E) 060898 /... S/1998/720 English Page 2 Annex Press statement issued 5 August 1998 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State of Eritrea The Ministerial Committee of the Organization of African Unity on the border conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia will submit its recommendations to the Heads of State of the three countries in the next few days. The Committee underlined that these recommendations "will be fair and will take into account the legitimate concerns of the parties and the ideals of the Organization of African Unity". The Ministerial Committee, which is composed of Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe and Djibouti, was convened at Ouagadougou from 1 to 2 August 1998 to review the findings of the Committee of Ambassadors that had visited Eritrea and Ethiopia earlier in July. Separate sessions with the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Eritrea and Ethiopia were also held to exchange views and explore avenues for a peaceful solution. -

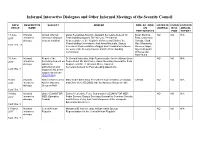

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (As of 13 December 2019)

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (as of 13 December 2019) DATE/ VENUE DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFERS NON‐SC / LISTED IN: NAME NON‐UN PARTICIPANTS JOURNAL SC ANNUAL POW REPORT 27 November 2019 Informal Peace consolidation in Abdoulaye Bathily, former head of the UN Regional Office for Central None NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive West Africa/UNOWAS Africa (UNOCA) and the author of the independent strategic review of dialogue the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS); Bintou Keita (Assistant Secretary‐General for Africa); Guillermo Fernández de Soto Valderrama (Permanent Representative of Colombia and Peace Building Commission Chair) 28 August 2019 Informal The situation in Burundi Michael Kingsley‐Nyinah (Director for Central and Southern Africa United Republic of NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 6 interactive Division, DPPA/DPO), Jürg Lauber (Switzerland PR as Chair of PBC Tanzania dialogue Burundi configuration) 31 July 2019 Informal Peace and security in Amira Elfadil Mohammed Elfadil (AU Comissioner for Social Affairs), Democratic Republic NO NO N/A Conf. Room 7 interactive Africa (Ebola outbreak in David Gressly (Ebola Emergency Response Coordinator), Mark Lowcock of the Congo dialogue the DRC) (Under‐Secretary‐General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator), Michael Ryan (WHO Health Emergencies Programme Executive Director) 7 June 2019 Informal The situation in Libya Mr. Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General of the European External none NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive (Resolution 2292 (2016) Action Service dialogue implementation) 21 March 2019 Informal The situation in the Joost R. Hiltermann (Program Director for Middle East & North Africa, NO NO N/A Conf. -

II. United Nations and Sub-Saharan Africa

II. United Nations and Sub-Saharan Africa The new UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, declared Africa, and in particular the crisis in Darfur, as a priority on his agenda. He made his fi rst trip in offi ce to the AU summit in Addis Ababa in January. The appointment of Asha-Rose Migiro as the deputy secretary general on 5 January was a signifi cant sign in itself. The former Tanzanian foreign minister became the second woman in history in this position and the highest-ranking woman at the UN. Another high-profi le appointment took place in July: Eritrean Haile Menkerios, former senior Department of Political Affairs (DPA) offi cial for African affairs, assumed the position as assistant secretary general for political affairs. Partnerships continued to be a buzzword. For instance, the Security Council stressed the importance of boosting the resources and capacity of the AU after a meeting organised on the initiative of South Africa, as part of its proactive approach to holding the presidency of the Council during March. Nonetheless, mutual understandings and clarity with regard to duties and responsibilities remained weak. The secretary general removed the Offi ce of the Special Advisor on Africa (OSAA) in July. The offi ce had been leaderless since 9 February, with the resignation of Legwaila Joseph Legwaila, the special advisor on Africa appointed by Kofi Annan. The OSAA mandate was consolidated with the offi ce of the high representative for the Least Developed Countries (LDC), Landlocked Develop- ing Countries (LLDC) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Cheick Sidi Diarra was appointed as high representative for this merged offi ce. -

Security Council Provisional Seventy-Second Year

United Nations S/ PV.8043 Security Council Provisional Seventy-second year 8043rd meeting Tuesday, 12 September 2017, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Alemu ..................................... (Ethiopia) Members: Bolivia (Plurinational State of) ..................... Mr. Llorentty Solíz China ......................................... Mr. Wu Haitao Egypt ......................................... Mr. Aboulatta France ........................................ Mrs. Gueguen Italy .......................................... Mr. Cardi Japan ......................................... Mr. Kawamura Kazakhstan .................................... Mr. Umarov Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Iliichev Senegal ....................................... Mr. Seck Sweden ....................................... Mr. Skoog Ukraine ....................................... Mr. Vitrenko United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Allen United States of America .......................... Ms. Sison Uruguay ....................................... Mr. Bermúdez Agenda Security Council mission Briefing by Security Council mission to Ethiopia (6 to 8 September 2017) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation -

Stabilising the Congo

FORCED MIGRATION POLICY BRIEFING 8 Stabilising the Congo Authors Emily Paddon Guillaume Lacaille December 2011 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford Forced Migration Policy Briefings The Refugee Studies Centre’s (RSC) Forced Migration Policy Briefings series seeks to stimulate debates on issues of key interest to researchers, policy makers and practitioners from the fields of forced migration and humanitarian studies. Policy briefing number 8 is a follow-up to a series of RSC inter-related activities on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that took place in 2010 and 2011, including a special issue of Forced Migration Review and an experts’ workshop on ‘the dynamics of conflict and forced migration in the DRC’ as well as dissemination and consultations in the DRC. Written by academic experts, the briefings provide policy-relevant research findings in an accessible format. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Refugee Studies Centre, its donors or to the University of Oxford as a whole. Direct your feedback, comments or suggestions for future briefings to the series editor, Héloïse Ruaudel ([email protected]). Further details about the series and all previous papers may be found on the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/policy-briefings). Contents Glossary of acronyms 1 Executive summary 2 1. The Congo context: the causes of persistent conflict 5 2. Stabilisation in the Congo: the policy 8 3. The results: stabilisation in practice 13 4. Stabilisation in the Congo: the politics 19 5. -

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council DATE/ DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFER NON- SC / NON- LISTED IN LISTED LISTED IN VENUE NAME UN JOURNAL IN SC ANNUAL PARTICIPANTS POW REPORT 19 June Informal Annual informal Oscar Fernández-Taranco, Assistant Secretary-General for Brazil, Burkina NO NO N/A 2017 interactive interactive dialogue Peacebuilding Support; Tae-Yul Cho, Permanent Faso, Cameroon, dialogue on peacebuilding Representative of the Republic of Korea and Chair of the Canada, Chad, Peacebuilding Commission; Ihab Awad Moustafa, Deputy Mali, Mauritania, Conf. Rm. 12 Permanent Representative of Egypt and Coordinator between Morocco, Niger, the work of the Security Council and the Peacebuilding Nigeria Republic Commission of Korea and Switzerland 15 June Informal Report of the Dr. Donald Kaberuka, High Representative for the African Union NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Secretary-General on Peace Fund, Mr. Atul Khare, Under-Secretary-General for Field dialogue options for Support, and Mr. El-Ghassim Wane, Assistant authorization and Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations Conf. Rm. 7 support to AU peace support operations (S/2017/454) 9 June Informal Haiti / Activities of the Marc-André Blanchard, Permanent Representative of Canada Canada NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Ad Hoc Advisory and Chair of the ECOSOC Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti dialogue Group on Haiti Conf. Rm. 7 31 May Informal Libya / EUNAVFOR Enrico Credentino, Force Commander of EUNAVFOR MED; NO NO N/A 2017 interactive MED (Operation Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General for Common Security dialogue Sophia) and Defence Policy and Crisis Response at the European External Action Service Conf. -

Peace and Security in Africa: a United Nations – African Union Priority

UNOAU Bulletin A publication from the United Nations Office to the African Union June - July, 2018 Peace and Security in Africa: A United Nations – African Union Priority The UN Deputy-Secretary-General, Amina J. Mohammed (fourth from right), joins AU Chairperson, Moussa Faki Mahamat (seventh from left), and Heads of African Governments and Representatives at the 31st Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union in Nouakchott, Mauritania “I increasingly see African leaders and citizens working together to build a great Africa. The United Nations will ensure that the African Union ambition in its Agenda 2063 is realized through the 2030 Agenda for people and planet” UN Deputy Secretary-General, Amina J. Mohammed at the 31st Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union Profiles Incoming Special Representative of the Outgoing Special Representative of the Secretary-General to the African Union Secretary-General to the African Union UNOAU Mandate and Head of UNOAU, and Head of UNOAU, Background on the establishment of UNOAU Sahle-Work Zewde Haile Menkerios Since the transformation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) into the African Union (AU) in 2002 and United Nations Secretary- United Nations Secretary- particularly since the 2004 launching of the AU peace and security architecture, there has been strong support General António General Ban Ki-moon among the UN and its Member States for closer UN cooperation with the AU. In 2005, the World Summit Guterres announced appointed Haile underscored the need to devote attention to the special needs of Africa. -

Documenting the Ethiopian Student Movement: an Exercise in Oral History

Documenting the Ethiopian Student Movement: An Exercise in Oral History ግማሽ ጋሬ እንጀራ እጐሰጉስና አንድ አቦሬ ውሀ እደሽ አደርግና ሣር እመደቤ ላይ እጐዘጉዝና ድሪቶ ደርቤ እፈነደስና ተመስገን እላለሁ ኑሮ ተገኘና፡፡ edited by Bahru Zewde Documenting the Ethiopian Student Movement: An Exercise in Oral History Documenting the Ethiopian Student Movement: An Exercise in Oral History edited by Bahru Zewde Forum for Social Studies © 2010 by the editor and Forum for Social Studies (FSS) Reprinted in 2010 All rights reserved Printed in Addis Ababa Typesetting & Layout: Konjit Belete ISBN: 978-99944-50-33-6 Forum for Social Studies (FSS) P.O.Box 25864 code 1000 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Email: [email protected] Web: www.fssethiopia.org.et Cover: an excerpt from the poem “Dehaw Yenageral” (“The Poor Man Speaks Out!”) recited by Tamiru Feyissa at the 1961 College Day FSS gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Department for International Development (DFID, UK), the Embassy of Denmark, the Embassy of Ireland, and Norwegian Church Aid - Ethiopia which has made this publication possible. Contents Page Acronyms ii Preface iii Introduction 1 I “Innocuous Days” 19 II The Radicalization Process 33 III Student Organizations 45 IV Demonstrations and Embassy Occupations 83 V The National Question 97 VI The Gender Question 117 VII The High School Factor 129 VIII From Student Union to Leftist Political Organization 141 Annexes Annex 1 Retreat Program 155 Annex 2 Participants’ Profile 159 Annex 3 Recommended Guidelines 161 Acronyms AAU Addis Ababa University AESM All Ethiopia Socialist Movement COSEC -

Rural and Urban Land Reform in Ethiopia

LTC Reprint No. 135 April 1978/ U.S. ISSN O o-NO7 Rural and Urban Land Reform in Ethiopia John M. Cohen Peter H. Koehn LAN TENURE CENTER University of Wisconsin-Madison Reprinted by permission from African Law Studies, No. 149/19'/7. RURAL AND URBAN LAND REFORM IN ETHIOPIA John M. Cohen Peter H. Koehn I. INTRODUCTION On September 12, 1974, military leaders of Ethiopia's creeping coup d'etat placed Emperor Haile Selassie I under ar rest and quickly formed a provisional military government. Later, during the evening of November 23rd, the military order ed the execution of 60 influential aristocrats, high government officials and military officers--including 18 generals, two prime ministers, a number of former cabinet ministers, and pro vincial governors closely associated with Haile Selassie's re gime. in March 1975, the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC) officially terminated the ruling monarchy and began to promulgate a series of radical socialist measures (Koehn, 1975; Harbeson, 1975b; Legu-n, 1975; Thompson, 1975). The PAC's actions had drastically altered the social, politi cal and economic structure of Ethiopia's cities, towns and countryside by 1976. Today, as when the coup d'etat took place, 85 percent of Ethiopia's population derive their livelihood front agriculture related activities. Agrarian producticn as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product ranks among the highest in the world, ranging between 55 and 60 percent. 1 Yet most of the rural peo ple live a tenuous subsistence existence. Expansion of agri cultural production barely averaged two percent per year in the pre-coup period. -

Toward a More Effective UN-AU Partnership on Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management

OCTOBER 2019 Toward a More Effective UN-AU Partnership on Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management DANIEL FORTI AND PRIYAL SINGH Cover Photo: UN emblem, October 3, ABOUT THE AUTHORS 2017. UN Photo/Cia Pak; AU medallion, May 21, 2015. Andrew Moore. DANIEL FORTI is a Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the authors Email: [email protected] and not necessarily those of the PRIYAL SINGH is a Researcher at the Institute for Security International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide Studies. range of perspectives in the pursuit of Email: [email protected] a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Vice President IPI and ISS owe a debt of gratitude to their many donors Albert Trithart, Editor for their generous support. They are particularly grateful to the government of Norway and the Training for Peace Project for funding this research initiative. The organiza- Suggested Citation: tions are also thankful for the AU Permanent Observer Daniel Forti and Priyal Singh, “Toward a More Effective UN-AU Partnership on Mission to the UN for its support to the project. Conflict Prevention and Crisis The authors would like to thank the many UN and AU Management,” International Peace officials, member-state representatives, and independent Institute and Institute for Security experts who shared their insights and perspectives during Studies, October 2019. interviews conducted in New York and Addis Ababa. The authors are also grateful to the individuals who provided © by International Peace Institute, 2019 All Rights Reserved feedback on earlier drafts of this report, including Jake Sherman, Gustavo de Carvalho, Annette Leijenaar, Liezelle www.ipinst.org Kumalo, Muneinazvo Kujeke, Sarah Taylor, Gretchen Baldwin, Marta Bautista Forcada, Gabriel Delsol, and John Hirsch. -

“We Are the Prisoners of Our Dreams:“ Long-Distance Nationalism and the Eritrean Diaspora in Germany

“We are the Prisoners of our Dreams:“ Long-distance Nationalism and the Eritrean Diaspora in Germany Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie im Fachbereich Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Bettina Conrad aus Simmern/Hunsrück Hamburg, April 2010 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 14. Juli 2010 Copyright Bettina Conrad, 2012 Content __________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements iv Illustrations vi Abbreviations viii Glossary ix Introduction 1 The absent diaspora (or how I came to research “Eritrea Abroad”) 2 Researching “Eritrea Abroad”: chances and challenges 8 Some relevant themes and research questions 15 Conceiving the Eritrean diaspora: key terms and concepts 17 Overview and organisation 24 Chapter 1: From Exile to Diaspora: A Short History of the Eritrean Refugee Community in Germany 28 Of nationalism and exile: a background note on the beginnings of the Eritrean struggle 26 Early years of exile in Europe: before the EPLF, before “Unity in Diversity” 34 Eritreans for Liberation and the EPLF’s struggle for domination at home and abroad 40 Mass-flight and mass-mobilization: building the EPLF’s “infrastructure of absorption” 44 Adi ertra abroad: life in exile and the need for community 51 Beyond adi ertra: mobilising international solidarity and financial support 54 Free at last: going back or staying on? 60 i Chapter 2: “A Culture of War and a Culture of Exile.” Young Eritreans in -

UNOAU Special News Bulletin: the UN at the AU Summit

UNOAU News Bulletin Special news March 2016 No 1 The United Nations at the 26thAfrican Union Summit UN and AU: Strengthening strategic partnership in Africa AMEYIB Communication & Marketing Plc Tel.: +251 11 126 2946/81, E-mail:[email protected], Website:www.acm.com.et Inside the Page Bulletin 03 UN and AU: Strengthening strategic partnership in Africa 04 UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon at the AU Summit 06 Election of the 15 members of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union 07 Side Events UNOAU, UNOWA and UNOCA at the AU Conference in support of the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram 08 IGAD Council of Ministers 55th Extra ordinary Session UN SRSG Kobler M. addressed the fifth meeting of International Contact group for Libya 10 Peace and Security Council meeting : AU Heads of State and Government expressed gratitude to the UN during their deliberations on Burundi and South Sudan 12 UN Special Envoy, Hiroute G. participated in the 4TH meeting of Special Envoys and Representatives on the Sahel 13 8th Gender Pre-Summit Meeting: AUC Chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma urged Women to be Transformers and not just Conformers. 15 United Nations and African Union Joint Task Force annual meeting 16 UNOAU SRSG good offices during the Summit 17 The United Nation Office to the African Union: mandate UN and AU: Strengthening strategic partnership in Africa he African Union Ordinary Summit is the gathering of all key policy organs of the AU. Two Tordinary Summits are held every year, one in January in Addis Ababa and the second in June in another African capital.