Understanding the Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anglicanorum Cœtibus While Maintaining Some of the Features of Anglicanism

THE ANGELUS ENGLISH-LANGUAGE ARTICLE REPRINT Let your speech be “Yes, yes: no, no”; whatever is beyond these comes from the evil one. (Mt. 5:37) G April 2010 Reprint #91 ” “ANGLICANORUM CONFUSIO The Canterbury Cross– Symbol of the Anglican Use Society. Some Initial Refl ections on “Anglican Use” has two mean- ings. First, it refers to former congregations of the Angli- the Apostolic Constitution can Communion who have joined the Catholic Church (Latin Rite in particular) Anglicanorum Cœtibus while maintaining some of the features of Anglicanism. It is still too soon to evaluate the recent institution of Personal Ordinariates These parishes were formerly by the Holy See in order to welcome groups from the Anglican Church who members of the Episcopal no longer feel at home in their original denomination because of the blessing Church in the United States of homosexual unions and the administration of the [purported] sacrament of of America and were allowed 1 to join the Catholic Church orders to declared homosexuals and women. Our intention is not to address under the Pastoral Provision all the problems raised by the Apostolic Constitution; however, the delicate of 1980 issued by Pope John question of ecclesiastical celibacy inevitably springs to mind as well as the Paul II. Anglican Use parishes repercussions the situation could have even though it is presented as transitory. currently exist only in the Also, we think that it would be unjust to pass over or to minimize because United States. Many Anglican of related problems an indubitably positive aspect: the quest for union with Use priests are former clergy Rome by a signifi cant portion of the Anglican Church. -

Mortal Vs. Venial Sin

Mortal vs. Venial Sin UNIT 3, LESSON 4 Learning Goals Connection to the ӹ There are different types of sin. Catechism of the ӹ All sins hurt our relationship with God. Catholic Church ӹ Serious sin — that is, completely turning ӹ CCC 1854 away from God — is called mortal sin. ӹ CCC 1855 ӹ Less serious sin is called venial sin. ӹ CCC 1857 ӹ CCC 1858 ӹ CCC 1859 ӹ CCC 1862 ӹ CCC 1863 Vocabulary ӹ Charity ӹ Mortal Sin ӹ Venial Sin BIBLICAL TOUCHSTONES If anyone sees his brother sinning, if the sin is Be sure of this, that no immoral or impure or not deadly, he should pray to God and he will greedy person, that is, an idolater, has any give him life. This is only for those whose sin is inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of not deadly. There is such a thing as deadly sin, God. about which I do not say that you should pray. EPHESIANS 5:5 All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that is not deadly. 1 JOHN 5:16-17 © SOPHIA INSTITUTE FOR TEACHERS 155 Lesson Plan Materials ӹ Failure-to-Love Slips ӹ Understanding Mortal Sin DAY ONE Warm-Up A. Ask students to recall the Good vs. Evil activity they completed earlier in the unit, and to recall some good and evil characters from their lists. Keep a list on the board. B. Based on the list, ask students again to identify the basic differences between good and evil. If necessary, lead students to the conclusion that good seeks what is best for others while evil seeks its own interests and destroys the happiness of others. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

Second Sunday of Advent SIXTH of DECEMBER, Ad 2020

SAINT BARNABAS CHURCH A ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH OF THE ORDINARIATE OF THE C HAIR OF SAINT PETER OMAHA, NEBRASKA Second Sunday of Advent SIXTH OF DECEMBER, ad 2020 Welcome to Saint Barnabas Church Founded in 1869, Saint Barnabas is a Roman Catholic parish of the Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter. The Ordinariate was established in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI in order to preserve elements of the Anglican tradition within the Catholic Church. The parish entered the Catholic Church in 2013. Mass is celebrated using Divine Worship, the Vatican- promulgated Missal also known as the Ordinariate or Anglican Use liturgy. All Catholics may fulfill their Mass obligation on Sundays and holydays at Saint Barnabas. Catholics in full communion with the Holy See of Rome may receive Holy Communion at our Masses. Confessions are heard beginning 25 minutes before Mass in the chapel off the right-hand side of the nave. KALENDAR Sunday, December 6 FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT pro populo Monday, December 7 Saint Ambrose, Bishop & Doctor Tuesday, December 8 IMMACULATE CONCEPTION 11:15 pro populo 7:00 Father James Brown Wednesday, December 9 Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin Thursday, December 10 Our Lady of Loreto Friday, December 11 Saint Damasus I, Pope Saturday, December 12 Our Lady of Guadalupe Sunday, December 13 THIRD SUNDAY OF ADVENT Gaudete pro populo Parish Finances OFFERINGS: $1,958 FOR THE WEEK ENDING NOVEMBER 29 EXPENSES: INTERCESSIONS THE SICK AND OTHERS IN THE CHURCH & THE WORLD NEED OF PRAYER Pope Francis and Pope emeritus Benedict XVI Mel Bohn, Helmuth Dahlke, Jane Dahlke, Bishop Steven Lopes [Ordinariate] Heather De John, James and Kathryn Drake, Archbishop George Lucas [Omaha] Ronald Erikson, Grantham family, Kelly President Donald Trump Leisure, Fran Nich, Julie Nich, Jack Rose, Jen Schellen, Barb Scofield, Paul Scofield, Joe Governor John Peter Ricketts Stankus, Marty Stankus, C. -

The Dogma of the Assumption in the Light of the First Seven Ecumenical Councils

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Reprints Marian Library Publications 1-1961 080 - The ogD ma of the Assumption in the Light of the First Seven Ecumenical Councils Gregory Cardinal Peter XV Agagianian Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_reprints Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Agagianian, Gregory Cardinal Peter XV, "080 - The oD gma of the Assumption in the Light of the First Seven Ecumenical Councils" (1961). Marian Reprints. Paper 97. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_reprints/97 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Reprints by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Gregory Peter XV Cardinal Agagianian is perhaps one of the best known of the non-American Cardinals. He has become familiar to Amer ican Catholic and non-Catholic readers because of the publicity given to his appointment to succeed Cardinal Stritch as Pro-prefect of the Sacred Congregation of the Faith in June, 1958. At this time and during the period following the death of the late Pius XII, he was considered by many observers as one of the most likely "candidates" for the Papacy. His two trips to the United States in 1954 and in May of this past year have served to bring him to the attention of the American public. Born in the Russian Caucasus sixty-five years ago, Cardinal Agagianian grew up in what is now Russian Georgia. -

Matins of Great and Holy Saturday (Friday Night)

Matins of Great and Holy Saturday (Friday Night) The priest, vested in a dark epitrachelion, opens the curtain, takes the censer, and begins: Priest: Blessed is our God always, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Reader: Amen. Glory to Thee, O God; glory to Thee! While the following prayers are being read, the priest censes the altar, the sanctuary, and the people. Reader: O Heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of Truth, Who art everywhere and fillest all things, Treasury of blessings, and Giver of Life, come and abide in us, and cleanse us from every impurity, and save our souls, O Good One. Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us! (3) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen. O most-holy Trinity, have mercy on us. O Lord, cleanse us from our sins. O Master, pardon our transgressions. O Holy One, visit and heal our infirmities for Thy name’s sake. Lord, have mercy. (3) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen. Our Father, Who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name. Thy Kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors, and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one. Priest: For Thine is the Kingdom, and the power, and the glory of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. -

The Divine Office

THE DIVINE OFFICE BRO. EMMANUEL NUGENT, 0. P. PIRITUAL life must be supplied by spiritual energy. An efficient source of spiritual energy is prayer. From Holy Scripture we learn that we should pray always. li In general, this signifies that whatever we do should be done for the honor and glory of God. In a more restricted sense, it requires that each day be so divided that at stated in tervals we offer to God acts of prayer. From a very early period it has been the custom of the Church, following rather closely the custom that prevailed among the Chosen People, and later among the Apostles and early Christians, to arrange the time for her public or official prayer as follows: Matins and Lauds (during the night), Prime (6 A.M.), Tierce (9 A.M.), Sext (12M.), None (3 P.M.), Vespers (6 .P. M.), Compline (nightfall). The Christian day is thus sanc tified and regulated and conformed to the verses of the Royal Psalmist: "I arose at midnight to give praise to Thee" (Matins), "Seven times a day have I given praise to Thee"1 (Lauds and the remaining hours). Each of the above divisions of the Divine Office is called, in liturgical language, an hour, conforming to the Roman and Jewish third, sixth, and ninth hour, etc. It is from this division of the day that the names are given to the various groups of prayers or hours recited daily by the priest when he reads his breviary. It is from the same source that has come the name of the service known to the laity as Sunday Vespers, and which constitutes only a portion of the Divine Office for that day. -

Some Symbols of Identity of Byzantine Catholics I Robert J

Some Symbols of Identity of Byzantine Catholics I Robert J. Skovira Introduction This essay is a descript�on of some of an ethnic group's symbols of identity2; itsa im is to explore the meanings of the following statement: [Byzantine Catholics] are no longer an immigrant and ethnic group. Byzantine Catholics are American in every sense of the word, that the rite itself is American as opposed to fo reign, and that both the rite and its adherents have become part and parcel of the American scene.;l This straight-forward statement claims that there ha been a rei nterpretation an d reexpression of identity within a new political and sociocultural envrionment.� It is common ense, for example, to think that individuals as a group do, re-do, rearrange, and change the expressions of values and beliefs in new situations. But, in order to ensure continuity in the midst of change, people will usually use already ex isting symbols-or whatever is at hand and fa miliar. Byzan tine Catholic identity is a case of new bottles with old wine. Ethnic groups and their members rely upon any number of factors to symbolize the values and beliefs with which they identify and by which they are identified. Such symbol of identity are manipulated, exploited, reinterpreted or changed, over time, according to the requirements of the context. In any event, people always use whatever is present to them for maintaining some continuity of identity while, at the same time, adjusting to new state -of-affairs. Herskovits shows, for exampl ,that We are dealing with a basi proce s in the adjustment of individual behavior and of institutional structures to be found in all situations where people having different ways of life come into con tact. -

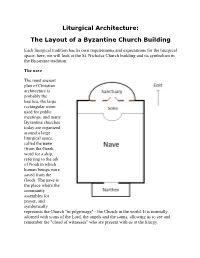

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

Mhfm Is the Hoax Not COVID-19 the Dimond Brothers Calumny & Detraction Against Jorge Clavellina Over a Difference of Secular Opinion

MhFM is the Hoax Not COVID-19 The Dimond Brothers Calumny & Detraction Against Jorge Clavellina Over a Difference of Secular Opinion "Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You clean the outside of the cup and dish, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence. Blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup and dish, and then the outside also will be clean." - St Matthew 23:25 Calumny: "Injuring another person's good name by lying." Detraction: “revealing another's sins to a third party who does not need to know about them.” The Catholic Church holds that the sins of Calumny and Detraction destroy the reputation and honor of one's neighbor. Honor is the social witness given to human dignity, and everyone enjoys a natural right to the honor of his name and reputation and to respect. Thus, detraction and calumny egregiously offend against the virtues of justice and charity. Both are mortal sins. Though Jorge Clavellina (a once devout MhFM supporter) and I stand on opposite sides of the V-II fence we none-the-less share the same position that the Dimond Brothers use the sins of Calumny and Detraction as their weapon of choice against any and all who oppose them. Jorge discovered just how debased and treacherous the Dimonds can be after quitting MhFM over a heated disagreement concerning his refusal to accept their erroneous claim that COVID-19 is a HOAX. Note: As I found Jorge’s original YouTube video "Coronavirus Fight. MHFM (vaticancatholic) FULL emails & Context" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GOU9gwo7qSc) .. -

The Slow Integration of Instruments Into Christian Worship

Musical Offerings Volume 8 Number 1 Spring 2017 Article 2 3-28-2017 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Jonathan M. Lyons Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Christianity Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lyons, Jonathan M. (2017) "From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship," Musical Offerings: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol8/iss1/2 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Document Type Article Abstract The Christian church’s stance on the use of instruments in sacred music shifted through influences of church leaders, composers, and secular culture. Synthesizing the writings of early church leaders and church historians reveals a clear progression. The early musical practices of the church were connected to the Jewish synagogues. As recorded in the Old Testament, Jewish worship included instruments as assigned by one’s priestly tribe. -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion.