Suggested Guidelines for Reptile Enrichment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many Groups of Organisms

Reptiles A. Cladistics 1. Many groups of organisms are “polyphyletic” a. This means that the group combines 2 or more lineages - example=fish 2. Cladistics follows only pure lineages going back in time - example Osteichthys B. Reptile Classifiecation - looks like a polyphyletic group 1. Dry skin - no loss of water through skin like amphibians 2. Aminotic egg - an egg that can survive on dry land - in contrast with the amphibian egg C. Mammals and Birds are derived from different lineages of reptiles (We will see below) D. Stem Reptiles 1. Different lineages based on the temporal region of their skulls - number of holes (or bars) a. These holes are necessary to accommodate large jaw muscles b. Anapsid Skull - no holes in temporal - jaws can move fast, but with little force 1. Muscles that move the jaw are small 2. There is no good paleotological evidence for the transition between amphibians and reptiles - no fossil intermediates a. Fossil amphibians have lots of dermal bones in skull b. Amphibians have no temporal openings in skull 1. (Aside) both fossil amphibians and primitive reptiles have a parietal “eye” that senses light and dark (“third” eye in middle of head) c. Reptile skull is higher than amphibian to accomodate larger jaw muscles d. Of the modern reptiles only turtles are anapsids 2. Diapsid Skull - has holes in the temporal region a. Diapsid reptiles gave rise to lizards and snakes - they have a diapsid skull 1. Also Tuatara, crocodiles, dinosaurs and pterydactyls Reptiles b. One group of diapsids also had a pre-orbital hole in the skull in front of eye - this hole is still preserved in the birds - this anatomy suggests strongly that the birds are derived from the diapsid reptiles 3. -

Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 8 7-31-2001 Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Andrew C. Skinner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Skinner, Andrew C. (2001) "Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol10/iss2/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Andrew C. Skinner Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10/2 (2001): 42–55, 70–71. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract The serpent is often used to represent one of two things: Christ or Satan. This article synthesizes evi- dence from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Greece, and Jerusalem to explain the reason for this duality. Many scholars suggest that the symbol of the serpent was used anciently to represent Jesus Christ but that Satan distorted the symbol, thereby creating this para- dox. The dual nature of the serpent is incorporated into the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon. erpent ymbols & SSalvation in the ancient near east and the book of mormon andrew c. -

Ostrich Production Systems Part I: a Review

11111111111,- 1SSN 0254-6019 Ostrich production systems Food and Agriculture Organization of 111160mmi the United Natiorp str. ro ucti s ct1rns Part A review by Dr M.M. ,,hanawany International Consultant Part II Case studies by Dr John Dingle FAO Visiting Scientist Food and , Agriculture Organization of the ' United , Nations Ot,i1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-21 ISBN 92-5-104300-0 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale dells Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1999 Contents PART I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE OSTRICH 5 Classification of the ostrich in the animal kingdom 5 Geographical distribution of ratites 8 Ostrich subspecies 10 The North -

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) by Richard Kissel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Kissel 2010 Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) Richard Kissel Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Based on dental, cranial, and postcranial anatomy, members of the Permo-Carboniferous clade Diadectidae are generally regarded as the earliest tetrapods capable of processing high-fiber plant material; presented here is a review of diadectid morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy, and paleozoogeography. Phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly of Diadectidae within Diadectomorpha, the sister-group to Amniota, with Limnoscelis as the sister-taxon to Tseajaia + Diadectidae. Analysis of diadectid interrelationships of all known taxa for which adequate specimens and information are known—the first of its kind conducted—positions Ambedus pusillus as the sister-taxon to all other forms, with Diadectes sanmiguelensis, Orobates pabsti, Desmatodon hesperis, Diadectes absitus, and (Diadectes sideropelicus + Diadectes tenuitectes + Diasparactus zenos) representing progressively more derived taxa in a series of nested clades. In light of these results, it is recommended herein that the species Diadectes sanmiguelensis be referred to the new genus -

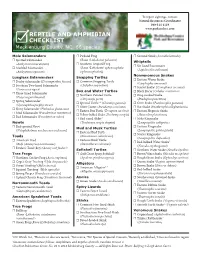

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

The Global Distribution of Tetrapods Reveals a Need for Targeted Reptile

1 The global distribution of tetrapods reveals a need for targeted reptile 2 conservation 3 4 Uri Roll#1,2, Anat Feldman#3, Maria Novosolov#3, Allen Allison4, Aaron M. Bauer5, Rodolphe 5 Bernard6, Monika Böhm7, Fernando Castro-Herrera8, Laurent Chirio9, Ben Collen10, Guarino R. 6 Colli11, Lital Dabool12 Indraneil Das13, Tiffany M. Doan14, Lee L. Grismer15, Marinus 7 Hoogmoed16, Yuval Itescu3, Fred Kraus17, Matthew LeBreton18, Amir Lewin3, Marcio Martins19, 8 Erez Maza3, Danny Meirte20, Zoltán T. Nagy21, Cristiano de C. Nogueira19, Olivier S.G. 9 Pauwels22, Daniel Pincheira-Donoso23, Gary Powney24, Roberto Sindaco25, Oliver Tallowin3, 10 Omar Torres-Carvajal26, Jean-François Trape27, Enav Vidan3, Peter Uetz28, Philipp Wagner5,29, 11 Yuezhao Wang30, C David L Orme6, Richard Grenyer✝1 and Shai Meiri✝*3 12 13 # Contributed equally to the paper 14 ✝ Contributed equally to the paper 15 * Corresponding author 16 17 Affiliations: 18 1 School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX13QY, UK. 19 2 Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology, The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, 20 Ben-Gurion University, Midreshet Ben-Gurion 8499000, Israel. (Current address) 21 3 Department of Zoology, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 6997801, Israel. 22 4 Hawaii Biological Survey, 4 Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI 96817, USA. 23 5 Department of Biology, Villanova University, Villanova, PA 19085, USA. 24 6 Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus Silwood Park, 25 Ascot, Berkshire, SL5 7PY, UK 26 7 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London NW1 4RY, UK. 27 8 School of Basic Sciences, Physiology Sciences Department, Universidad del Valle, Colombia. -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

Marine Reptiles Arne R

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Study of Biological Complexity Publications Center for the Study of Biological Complexity 2011 Marine Reptiles Arne R. Rasmessen The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts John D. Murphy Field Museum of Natural History Medy Ompi Sam Ratulangi University J. Whitfield iG bbons University of Georgia Peter Uetz Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Copyright: © 2011 Rasmussen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of Biological Complexity at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Biological Complexity Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review Marine Reptiles Arne Redsted Rasmussen1, John C. Murphy2, Medy Ompi3, J. Whitfield Gibbons4, Peter Uetz5* 1 School of Conservation, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America, 3 Marine Biology Laboratory, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences, Sam Ratulangi University, Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, 4 Savannah River Ecology Lab, University of Georgia, Aiken, South Carolina, United States of America, 5 Center for the Study of Biological Complexity, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, United States of America Of the more than 12,000 species and subspecies of extant Caribbean, although some species occasionally travel as far north reptiles, about 100 have re-entered the ocean. -

Meet the Herps!

Science Standards Correlation SC06-S2C2-03, SC04-S4C1-04, SC05-S4C1-01, SC04-S4C1-06, SC07-S4C3-02, SC08- S4C4-01, 02&06 MEET THE HERPS! Some can go without a meal for more than a year. Others can live for a century, but not really reach a ripe old age for another couple of decades. One species is able to squirt blood from its eyes. What kinds of animals are these? They’re herps – the collective name given to reptiles and amphibians. What Is Herpetology? The word “herp” comes from the word “herpeton,” the Greek word for “crawling things.” Herpetology is the branch of science focusing on reptiles and amphibians. The reptiles are divided into four major groups: lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocodilians. Three major groups – frogs (including toads), salamanders and caecilians – make up the amphibians. A herpetologist studies animals from all seven of these groups. Even though reptiles and amphibians are grouped together for study, they are two very different kinds of animals. They are related in the sense that early reptiles evolved from amphibians – just as birds, and later mammals, evolved from reptiles. But reptiles and amphibians are each in a scientific class of their own, just as mammals are in their own separate class. One of the reasons reptiles and amphibians are lumped together under the heading of “herps” is that, at one time, naturalists thought the two kinds of animals were much more closely related than they really are, and the practice of studying them together just persisted through the years. Reptiles vs. Amphibians: How Are They Different? Many of the differences between reptiles and amphibians are internal (inside the body). -

Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

LIZARDSLIZARDS && SNAKES:SNAKES: ALIVE!ALIVE! EDUCATOR’SEDUCATOR’S GUIDEGUIDE www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakeswww.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakes Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Must-Read Key Concepts and Background Information • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Activities to Extend Learning Back in the Classroom • Map of the Exhibition to Guide Your Visit • Correlations to California State Standards Special thanks to the Ellen Browning Scripps Foundation and the Nordson Corporation Foundation for providing underwriting support of the Teacher’s Guide KEYKEY CONCEPTSCONCEPTS Squamates—legged and legless lizards, including snakes—are among the most successful vertebrates on Earth. Found everywhere but the coldest and highest places on the planet, 8,000 species make squamates more diverse than mammals. Remarkable adaptations in behavior, shape, movement, and feeding contribute to the success of this huge and ancient group. BEHAVIOR Over 45O species of snakes (yet only two species of lizards) An animal’s ability to sense and respond to its environment is are considered to be dangerously venomous. Snake venom is a crucial for survival. Some squamates, like iguanas, rely heavily poisonous “soup” of enzymes with harmful effects—including on vision to locate food, and use their pliable tongues to grab nervous system failure and tissue damage—that subdue prey. it. Other squamates, like snakes, evolved effective chemore- The venom also begins to break down the prey from the inside ception and use their smooth hard tongues to transfer before the snake starts to eat it. Venom is delivered through a molecular clues from the environment to sensory organs in wide array of teeth. -

Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles)

6-3.1 Compare the characteristic structures of invertebrate animals... and vertebrate animals (fish, amphibians, and reptiles). Also covers: 6-1.1, 6-1.2, 6-1.5, 6-3.2, 6-3.3 Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles sections Can I find one? If you want to find a frog or salamander— 1 Chordates and Vertebrates two types of amphibians—visit a nearby Lab Endotherms and Exotherms pond or stream. By studying fish, amphib- 2 Fish ians, and reptiles, scientists can learn about a 3 Amphibians variety of vertebrate characteristics, includ- 4 Reptiles ing how these animals reproduce, develop, Lab Water Temperature and the and are classified. Respiration Rate of Fish Science Journal List two unique characteristics for Virtual Lab How are fish adapted each animal group you will be studying. to their environment? 220 Robert Lubeck/Animals Animals Start-Up Activities Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles Make the following Foldable to help you organize Snake Hearing information about the animals you will be studying. How much do you know about reptiles? For example, do snakes have eyelids? Why do STEP 1 Fold one piece of paper lengthwise snakes flick their tongues in and out? How into thirds. can some snakes swallow animals that are larger than their own heads? Snakes don’t have ears, so how do they hear? In this lab, you will discover the answer to one of these questions. STEP 2 Fold the paper widthwise into fourths. 1. Hold a tuning fork by the stem and tap it on a hard piece of rubber, such as the sole of a shoe.