Borders Committee Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBX Case Study

C A SE S TUDY | CROSS BORDER XPRESS (CBX) Maximizing Airport Operational Efficiency The Challenge The international border between the United States and Mexico is the most frequently crossed border in the world. In total, there are 48 U.S.-Mexico border crossings with 330 ports of entry. Cross Border Xpress (CBX) is a terminal located in San Diego, California, with a 390-foot pedestrian bridge connecting it to the Tijuana International Airport in Tijuana, Mexico. It provides easy and direct access for ticketed passengers from the U.S. side to clear Mexican immigration and catch their flight at the Tijuana airport, and for passengers arriving in Tijuana to cross into U.S. Cross Border Express at a Glance customs and exit on the U.S. side. SAFR anonymous video analytics helps improve airport operational efficiency. CBX is open 24 hours a day, and with more than a million passengers crossing each year, it is important to ensure Location: Tijuana, Mexico – both a safe and efficient passenger experience, and a San Diego, CA, USA secure border crossing. CBX needed a real-time automated solution that could count the number of Deployment Type: Anonymous video analytics people crossing, track the time it takes to cross from one Features: People counting, traversal time end of the bridge to the next, and identify any irregularity analysis, mask detection in passenger flow in order to alert security and operations personnel to potential safety problems, Use Cases: Real-time anonymous video unauthorized movement, or inefficiencies. analytics The SAFR Solution on live video feeds, in motion, under poor lighting condi- To address CBX’s need for actionable, real-time analytics, tions, and even partially obscured. -

Air Quality Planning and Transportation Conformity

Appendix C: Air Quality Planning and Transportation Conformity Draft for Public Review May 2021 Appendix C: Air Quality Planning and Transportation Conformity Executive Summary The San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), as the region’s Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), must make a transportation air quality conformity determination for regional transportation plans (RTPs) and regional transportation improvement programs (RTIPs). The purpose of transportation conformity is to ensure that federally funded or approved activities are consistent with the State Implementation Plan (SIP). This ensures that no transportation activities will cause or contribute to new air quality violations, worsen existing violations, or delay the attainment of any relevant National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). This report documents a demonstration of conformity for the 2008 and 2015 Ozone NAAQS for San Diego Forward: The 2021 Regional Plan (2021 Regional Plan) and the 2021 Regional Transportation Improvement Program (2021 RTIP), as amended. The 2021 Regional Plan serves as the region’s Regional Transportation Plan (RTP). Background The federal Clean Air Act (CAA), which was last amended in 1990, requires the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) to set NAAQS for pollutants considered harmful to public health and the environment. California has adopted state air quality standards that are more stringent than the NAAQS.1 Areas with levels that violate the standard for specified pollutants are designated as nonattainment areas. The U.S. EPA requires that each state containing nonattainment areas develop and adopt plans to attain the NAAQS by a specified attainment deadline. These attainment plans are called SIPs. The San Diego County Air Pollution Control District (SDAPCD), in collaboration with California Air Resources Board (CARB), prepares the San Diego portion of the California SIP. -

Lessons from San Diego's Border Wall

RESEARCH REPORT (CBP Photo/Mani Albrecht) LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL The limits to using walls for migration, drug trafficking challenges By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer December 2017 " The border doesn’t need a wall. It needs better-equipped ports of entry, investi- gative capacity, technology, and far more ability to deal with humanitarian flows. In its current form, the 2018 Homeland Security Appropriations bill is pursuing a wrong and wasteful approach. The ex- perience of San Diego makes that clear." LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL December 2017 | 2 SUMMARY The prototypes for President Trump's proposed border wall are currently sitting just outside San Diego, California, an area that serves as a perfect example of how limited walls, fences, and barriers can be when dealing with migration and drug trafficking challenges. As designated by stomsCu and Border Protection, the San Diego sector covers 60 miles of the westernmost U.S.-Mexico border, and 46 of them are already fenced off. Here, fence-building has revealed a new set of border challenges that a wall can’t fix. The San Diego sector shows that: • Fences or walls can reduce migration in urban areas, but make no difference in rural areas. In densely populated border areas, border-crossers can quickly mix in to the population. But nearly all densely populated sections of the U.S.-Mexico border have long since been walled off. In rural areas, where crossers must travel miles of terrain, having to climb a wall first is not much of a deterrent. A wall would be a waste of scarce budget resources. -

Opportunities for Regional Collaboration on the Border: Sharing the European Border Experience with the San Diego/Tijuana Region

Opportunities for Regional Collaboration on the Border: Sharing the European border experience with the San Diego/Tijuana region Dr. Freerk Boedeltje, Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias, San Diego State University, May 2012 How to read this white paper? This white paper highlights best practices and barriers for local cross border cooperation across the European Union and will suggest policy options relevant to the San Diego-Tijuana region. The research done in Europe has been carried out as part of two large scheme EU wide projects sponsored under the 5th and 6th framework Programme of European Commission. Code named EXLINA and EUDIMENSIONS, the research consisted of a consortium of multiple universities across the European Union and took 8 years between 2002 and 2009. Both project have sought to understand the actual and potential role of cross border co-operation beyond the external borders of the EU and focused on specific local development issues, including economic development, cultural and educational matters, urban development, local democracy and environmental issues. The research was designed to address practical aspects of cross-border co- operation across and beyond the external borders of the European Union. The case studies that covered most part of the external borders of the EU centred on how changes within Europe’s political space are being interpreted and used by actors with a stake in bi-national/cross-border cooperation. This whitepaper compares and contrast the San Diego-Tijuana realities with cross border cooperation in border regions of the European Union. In addition to improving our understanding how local border regions function within a global context, the whitepaper highlight best practices and barriers for local cross border cooperation and will suggest policy options relevant to the San Diego Region and the Tijuana Tecate and Playas de Rosarito Metropolitan Zone. -

Vier Portillo

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 444444444444444444444444U JAVIER PORTILLO, Petitioner, - v - UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. 4444444444444444444444444U PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT 4444444444444444444444444U ELIZABETH A. MISSAKIAN P.O. Box 601879 San Diego, CA 92160 (619) 233-6534 Counsel for Petitioner JAVIER PORTILLO LIST OF PARTIES [X All parties appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. [] All parties do not appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. - prefix - QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Whether the Ninth Circuit’s analysis of the facts was inadequate and whether, when the entirety of facts presented at trial was considered, there was sufficient evidence that petitioner Javier Portillo had knowledge of narcotics hidden in his vehicle at the time he crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. - prefix - TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.. iii OPINION BELOW. 1 JURISDICTION. 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS. 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE . 2 STATEMENT OF FACTS. 3 Government’s Case-in-Chief. 3 Defense Case. 8 Testimony of Javier Portillo. 9 REASON TO GRANT THE WRIT. 11 THERE WAS INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE FOR THE JURY TO CONCLUDE THAT JAVIER PORTILLO KNEW OF THE PRESENCE OF NARCOTICS WITHIN HIS VEHICLE WHEN HE CROSSED INTO THE UNITED STATES AT THE SAN YSIDRO PORT OF ENTRY.. 12 A. The Claim is Preserved.. 12 B. Standard of Review . 12 C. Evidence at Trial Was Insufficient to Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that Javier Portillo Knew There Were Narcotics in his Vehicle. -

Gateway Parking

GATEWAY PARKING STABILIZED INCOME INVESTMENT OFFERING MEMORANDUM INVESTMENT ADVISORS CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT JOSEPH LISING The information contained in the following offering memorandum is proprietary Managing Director and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it Irvine Office from Cushman & Wakefield and it should not be made available to any other person +1 949 372 4896 Direct or entity without the written consent of Cushman & Wakefield. By taking possession +1 949 474 0405 Fax [email protected] of and reviewing the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and Lic. 01248258 treat all such information in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject property now, please return this offering memorandum to Cushman & Wakefield. This offering memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified financial and physical information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Cushman & Wakefield has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCBs or asbestos, the compliance with local, state and federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

Business PAGE 9 Vol 6, Issue 1

U.S. Customsrontline and Border Protection H Vol 6, Issue 1 CBP gets America Back to Business PAGE 9 Vol 6, Issue 1 CONTENTS H COVER STORY 9 Business Unusual When Mother Nature strikes or other major events disrupt normal border operations, CBP’s business recovery program keeps traffic flowing and protects the U.S. economy. 9 H FEATURES 18 Riding Shotgun in the Arizona Skies Specially trained Border Patrol agents and CBP officers accompany Air and Marine pilots as supplemental air crew members. 22 Transformation at Land Border Ports of Entry 18 CBP’s land border ports of entry now benefit from improved technologies and resource optimization. 22 H DEPARTMENTS H ON THE COVER 2 CBP In Photos 36 CBP History The Ambassador Bridge, connecting Detroit with Windsor, Canada, is North 4 Around the Agency 40 Border Busts America’s busiest commercial international border crossing. During fiscal year 2012, 28 In Focus 42 Resources an average of $136 million of cargo CBP In The Spotlight crossed the bridge into the U.S. each 34 day or $5.7 million of cargo each hour. Cover photo by Lisa Przybyla CELEBRATING THE CAREER OF DAVID V. AGUILAR 2 H CBP IN PHOTOS H ACTING COMMISSIONER RETIRES AFTER 34 YEARS OF DISTINGUISHED SERVICE Frontline VOL 6, ISSUE 1 SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY Janet Napolitano ACTING COMMISSIONER, U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION THOMAS S. WINKOWSKI ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER, OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Melanie Roe EDITOR Laurel Smith MANAGING EDITOR Jason McCammack CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Susan Holliday Marcy Mason PRODUCTION MANAGER Tracie Parker PHOTOGRAPHERS James R. -

Cross Border Survey

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents T ABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents. i List of Tables . iii List of Figures. iv Introduction. 1 Motivation for Study . 1 Overview of Methodology . 1 Organization of Report. 3 Acknowledgments . 3 Disclaimer . 3 About True North . 3 Key Findings . 4 Cross-border trips originate close to the border in México.. 4 Trip destinations in the U.S. cluster close to the border. 4 Shopping is the most common reason for crossing the border. 4 The average crosser visits multiple destinations in the U.S. and for a mix of reasons. 4 Most U.S. destinations are reached by driving alone or in a carpool. 5 The typical U.S. visit lasts less than one day. 5 Proximity to the border also shapes U.S. resident trips to México. 5 U.S. residents generally visit México to socialize. 5 The average México visit lasts two days.. 6 Interest in using the Otay Mesa East tolled border crossing was conditioned by several factors. 6 The current study findings are similar to the 2010 study findings . 6 México Resident: U.S. Trip Details. 8 Trip Origin in México . 8 Primary Destination in United States. 10 Primary U.S. Trip Purpose . 10 Duration of U.S. Visit . 12 Miles traveled in U.S. 13 Number of Destinations in the U.S.. 14 Time of Stops in U.S. 14 Duration of Stops in U.S. 18 Location of Destinations in San Diego County. 21 Purpose of Stops in San Diego County . 28 Mode of Travel in San Diego County . -

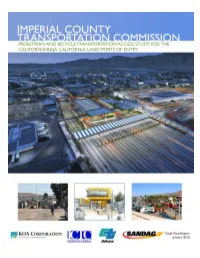

2.1 Description of Border Function

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................2 1.2 COMMUNITY AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT .........................................................................................................4 1.3 EXISTING CONDITIONS ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT ......................................................................................4 1.4 PROGRAMMED IMPROVEMENTS AND FUTURE CONDITIONS .............................................................................5 1.5 ORIGIN AND DESTINATION SURVEY RESULTS ..................................................................................................5 1.6 RECOMMENDED PROJECTS .................................................................................................................................5 1.7 FUNDING STRATEGY AND VISION .....................................................................................................................7 2.0 INTRODUCTION 8 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF BORDER FUNCTION ...............................................................................................................9 2.2 DEMOGRAPHIC DATA ...................................................................................................................................... 12 2.3 CROSSING AND WAIT TIME SUMMARIES ......................................................................................................... 14 2.4 ENVIRONMENTAL, HEALTH, -

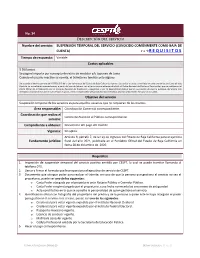

Ir a →R E Q U I S I T

No. 34 Descripción del servicio Nombre del servicio: SUSPENSIÓN TEMPORAL DEL SERVICIO (CONOCIDO COMÚNMENTE COMO BAJA DE CUENTA) Ir a R E Q U I S I T O S Tiempo de respuesta: Variable Costos aplicables $ 500 pesos Se paga el importe por concepto de retiro de medidor y/o taponeo de toma. Cuando el usuario reactive su cuenta, el trámite no tendrá costo alguno. De acuerdo al décimo párrafo del ARTÍCULO 9 de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California, vigente: Las tarifas y cuotas contenidas en cada una de las secciones de este Capítulo, se actualizarán mensualmente, a partir del mes de febrero, con el factor que se obtenga de dividir el Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor, que se publique en el Diario Oficial de la Federación por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, o por la dependencia federal que en sustitución de ésta lo publique, del último mes inmediato anterior al mes por el cual se hace el ajuste, entre el citado índice del penúltimo mes inmediato anterior al del mismo mes que se actualiza. Objetivo del servicio Suspensión temporal de los servicios es para aquellos usuarios que no requieran de los mismos. Área responsable: Coordinación Comercial correspondiente. Coordinación que realiza el Centro de Atención al Público correspondiente. servicio: Comprobante a obtener: Documento del pago del trámite. Vigencia: No aplica. Artículo 9, párrafo 7, de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California para el ejercicio Fundamento jurídico: fiscal del año 2021, publicada en el Periódico Oficial del Estado de Baja California en fecha 28 de diciembre de 2020. -

2013 San Diego

BINATIONAL HAZARDOUS MATERIALS PREVENTION AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN AMONG THE COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA AND THE CITY OF TIJUANA, BAJA CALIFORNIA January 14, 2013 Binational Hazardous Materials Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Among the County Of San Diego, the City of San Diego, California, and the City of Tijuana, Baja California January 14, 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2005-Present ...................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2003 .................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................... 10 PARTICIPATING AGENCIES................................................................................................... 17 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 23 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 23 1.0 TIJUANA/SAN DIEGO BORDER REGION ................................................................. 25 1.1 General Aspects of the Region ........................................................................................ 25 1.1.1 Historical and Cultural Background ................................................................ 25 1.1.2 Geographic Location -

General Services Administration Pacific Rim Region August 2018

Otay Mesa Land Port of Entry Draft Environmental Impact Statement Contents OTAY MESA LAND PORT OF ENTRY MODERNIZATION AND EXPANSION DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT OVERVIEW OTAY MESA, CALIFORNIA General Services Administration Pacific Rim Region August 2018 General Services Administration 1 Otay Mesa Land Port of Entry Draft Environmental Impact Statement Overview General Information GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT The United States (U.S.) General Services Administration (GSA) proposes the modernization and expansion of the existing Otay Mesa Land Port of Entry (LPOE). The Otay Mesa LPOE is located in Otay Mesa, a community in the southern section of the City of San Diego, California, just north of the international border between the U.S. and Mexico. The GSA has prepared this Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), which examines the purpose and need for this project; alternatives considered; the existing environment that could be affected; and the potential impacts resulting from each of the alternatives; and proposes best management practices and/or mitigation measures. The views and comments of the public are necessary to help determine the scope and content of the environmental analysis. A DEIS public meeting will be held on Wednesday, September 5, 2018 from 4 to 7 PM at: Holiday Inn Express and Suites San Diego 2296 Niels Bohr Court San Diego, CA 92154 619-710-0900 Comments on the Draft EIS must be received by Tuesday, October 9, 2018 and emailed to [email protected] or sent to: General Services Administration Attention: Osmahn Kadri, NEPA Project Manager 50 United Nations Plaza, 3345 Mailbox #9 San Francisco, CA 94102 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document can be made available in alternate formats.