PTA Models of Organisation for Regional Transport Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh PDF Map Citywide Website Small

EDINBURGH North One grid square on the map represents approximately Citywide 30 minutes walk. WATER R EAK B W R U R TE H O A A B W R R AK B A E O R B U H R N R U V O O B I T R E N A W A H R R N G Y E A T E S W W E D V A O DRI R HESP B BOUR S R E W A R U H U H S R N C E A ER R P R T O B S S S E SW E O W H U A R Y R E T P L A HE B A C D E To find out more To travel around Other maps SP ERU W S C Royal Forth K T R OS A E S D WA E OA E Y PORT OF LEITH R Yacht Club R E E R R B C O T H A S S ST N L W E T P R U E N while you are in the Edinburgh and go are available to N T E E T GRANTON S S V V A I E A E R H HARBOUR H C D W R E W A N E V ST H N A I city centre: further afield: download: R S BO AND U P R CH RO IP AD O E ROYAL YACHT BRITANNIA L R IMPERIAL DOCK R Gypsy Brae O A Recreation Ground NEWHAVEN D E HARBOUR D Debenhams A NUE TON ROAD N AVE AN A ONT R M PL RFR G PIE EL SI L ES ATE T R PLA V ER WES W S LOWE CE R KNO E R G O RAN S G T E 12 D W R ON D A A NEWHAVEN MAIN RO N AD STREET R Ocean R E TO RIN K RO IV O G N T IT BAN E SH Granton RA R Y TAR T NT O C R S Victoria Terminal S O A ES O E N D E Silverknowes Crescent VIE OCEAN DRIV C W W Primary School E Starbank A N Golf Course D Park B LIN R OSWALL R D IV DRI 12 OAD Park SA E RINE VE CENT 13 L Y A ES P A M N CR RIMR R O O V O RAN T SE BA NEWHAVEN A G E NK RO D AD R C ALE O Forthquarter Park R RNV PORT OF LEITH & A O CK WTH 14 ALBERT DOCK I HA THE SHORE G B P GRANTON H D A A I O LT A Come aboard a floating royal N R W N L O T O O B K D L A W T A O C O R residence or visit the dockside bars Scottish N R N T A N R E E R R Y R S SC I E A EST E D L G W N O R D T D O N N C D D and bistros; steeped in maritime S A L A T E A E I S I A A Government DRI Edinburgh College I A A M K W R L D T P E R R O D PA L O Y D history and strong local identity. -

View A876 T Clackmannanshire Bridge

TRANSPORT SCOTLAND SCOTTISH TRUNK ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT EVALUATION 3YA Evaluation Report for A876(T) Clackmannanshire Bridge TRANSPORT SCOTLAND SCOTTISH TRUNK ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT EVALUATION 3YA Evaluation Report for A876(T) Clackmannanshire Bridge CONTENTS Page 1 SUMMARY OF IMPACTS 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Operational Indicators – How is the project operating? 2 1.3 Process Indicators – How well was the project implemented? 2 1.4 Forecasting – How accurate were predictions? 3 1.5 Objectives – Has the project met its objectives? 4 1.6 Cost to Government – Is the project delivering value for money? 4 2 INTRODUCTION 7 2.1 Background to Project Evaluation 7 2.2 This Evaluation and Project Reported 8 2.3 Previous Evaluations 9 3 PROJECT EVALUATION 13 3.1 Introduction 13 3.2 Evaluation Methodology 15 3.3 The Operation of the Project 16 3.4 Environment 24 3.5 Safety 28 3.6 Economy 33 3.7 Accessibility & Social Inclusion 34 3.8 Integration 36 3.9 Cost to Government 38 3.10 Value for Money 39 3.11 Achievement of Objectives 40 3.12 Evaluation Summary 46 A ENVIRONMENT 49 A.1 Introduction 49 A.2 Environmental Findings 50 A.3 Three-Year After Review Findings 51 B METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES 66 B.1 Overview 66 B.2 Network Traffic Indicators 66 B.3 Environmental 69 B.4 Safety 69 B.5 Economy 70 B.6 Integration 71 B.7 Accessibility & Social Inclusion 71 B.8 Costs to Government 71 B.9 Value for Money 72 B.10 Achievement of Objectives 73 TABLES Page Table 2.1: Project Summary Details 8 Table 3.1: Traffic Analysis Summary 21 Table 3.2: Travel -

Transport and Environment Committee

Item 7.15 Transport and Environment Committee 10.00am, Thursday, 20 June 2019 Annual Update on Council Transport Arms Length Companies Executive/routine Executive Wards All Council Commitments N/A 1. Recommendations 1.1 Transport and Environment Committee is asked to: 1.1.1 Note the progress of the three Council arms length companies (Transport for Edinburgh (TfE), Edinburgh Trams Limited (ETL) and Lothian Buses (LB) over the past 12 months; and 1.1.2 Refer this report to Governance Risk and Best Value Committee for noting, as part of the Council’s governance arrangements. Paul Lawrence Executive Director of Place Contact: Paul Lawrence, Executive Director of Place E-mail: [email protected] | Tel: 0131 529 7325 Report Annual Update on the Council Transport Arms Length Companies 2. Executive Summary 2.1 This report sets out the progress made by TfE, ETL and LB over the last 12 months and is reported in line with the Council’s governance arrangements, which require an annual update on performance of arms length organisations. This is the first report on the Transport companies. 3. Background 3.1 On 22 August 2013, in establishing the arrangements for the operation of the new Edinburgh Tram, Council approved the establishment of TfE. This company now holds the Council’s shareholding in both LB and ETL. This shareholding is as follows: 100% of ETL and 91.01% of shares in LB (with the balance owned by East Lothian, West Lothian and Midlothian Councils). 3.2 The most recent update on the three companies was considered by Transport and Environment Committee on 17 January 2016. -

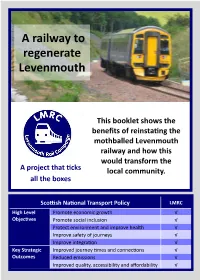

A Railway to Regenerate Levenmouth

A railway to regenerate Levenmouth This booklet shows the benefits of reinstating the mothballed Levenmouth railway and how this would transform the A project that ticks local community. all the boxes Scottish National Transport Policy LMRC High Level Promote economic growth √ Objectives Promote social inclusion √ Protect environment and improve health √ Improve safety of journeys √ Improve integration √ Key Strategic Improved journey times and connections √ Outcomes Reduced emissions √ Improved quality, accessibility and affordability √ CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Executive Summary 1 1.2 The Vision 2 1.3 The Proposal 3 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2.1 The mothballed Leven line 4 2.2 Population 6 2.3 Previous studies 8 2.4 Potential rail freight 10 2.5 Support for Levenmouth rail link 11 3. BENEFITS 3.1 Personal stories 12 3.2 What makes a good rail reopening project? 14 3.3 Delivering Scottish Government policy 15 3.4 Freight 16 3.5 Land Value Capture 17 3.6 Tourism 18 3.7 Wider economic and regional benefits 20 3.8 The business case - Benefit to Cost ratio 21 4. RE-INSTATING THE RAILWAY 4.1 Construction costs - Comparing Levenmouth with Borders 22 4.2 Timetable issues 24 4.3 Other project issues 25 5. MOVING FORWARD 5.1 Conclusions 26 5.2 The final report? 26 6. LEVENMOUTH RAIL CAMPAIGN 6.1 About our campaign 27 6.2 Our Charter 28 6.3 More information 29 - 1 - 1. Introduction 1.1 Executive Summary This booklet has been produced by the Levenmouth Rail Campaign (LMRC) with the support of a group of railway professionals who wish to lend their expertise to the campaign. -

Annual Report 2019-20

Annual Report 2019-20 Annual 19-Report 20 Annual Annual Report 2019-20 Report 2019-20 Contents 03 Foreword (Chair) 05 Who We Are 12 Our Activities 2019-20 31 European Projects 37 Appendix: Annual Accounts and Reports 38 Contact Information 2 Annual Report 2019-20 Foreword Our role providing strategic regional data and trends to produce a direction Main Issues Report. This is a precursor As a Regional Transport Partnership, to the development of a new Regional SEStran provides strategic direction. We Transport Strategy which will set out work to achieve common purpose across an ambitious course for transforming our eight local authority partners; we have transport and mobility across the region. a statutory duty to prepare a Regional Leading by example Transport Strategy (RTS) and keep it up to Last year SEStran continued to be actively date. The RTS provides the coordinating involved in demonstrating how innovative platform for the development of local changes in strategic transport, personal transport plans. It helps shape a wide mobility and logistics will work in the range of policies for regional and local south east of Scotland. land use, and economic development As Chair of SEStran, I am plans. It fosters a consistent approach Many of the projects we supported help immensely proud to present across our eight statutory partners. to tackle the most challenging issues that the annual report for 2019/20. we face today, and we have continued The challenges we now face as a region to collaborate on some of the most with a rapidly growing population, and Throughout the year, SEStran pro- innovative EU and Scottish projects in those we all face as a society from more actively developed strategies and order to bring the best of new approaches extreme weather events and climate studies, and supported projects that to our partners and region. -

SESTRAN RAIL STRATEGY From: DIRECTOR of PLANNING and ENVIRONMENT

8 .iENDA ITEM NO. ..... *3~.....-. NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: PLANNING & ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE Subject ROADS & TRANSPORTATION SUB COMMITTEE SESTRAN RAIL STRATEGY From: DIRECTOR OF PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT Date: 9" August 2000 Ref DITTI03I02ISCW 1. This report informs Committee of the development of a draft strategy in respect of future rail service provision in the South East Scotland Transport Partnership (SESTRAN) area. The approval of Committee is sought to the submission of the comments contained in this report as a response to the SESTRAN strategy. -Detail 2. The nine Councils in the South East Scotland Transport Partnership are working towards agreement on a strategy for the development of passenger rail services in the eastern central belt and the borders area. Some of the proposals relate only to the SESTRAN area but others have implications for North Lanarkshire. These latter are discussed below. 3. Edinburgh Airport Link The development of rail access served by GlasgowEdinburgh trains would open up opportunities for a direct rail connection from Cumbernauld and/or Croy to Edinburgh Airport. Edinburgh has direct flights to various other countries in Europe which are not available from Glasgow Airport. Access to Glasgow Airport itself is difficult at times because of congestion on the M8 through Glasgow city centre and the lack of a rail connection to that airport. The rail connection to Edinburgh Airport could therefore be attractive for businesses and residents in the Kilsyth and Cumbernauld area in terms of improving access to/from European destinations. 4. Edinburgh-Shotts-Glasgow Central SESTRAN propose an upgrade of the Shotts line including electrification. -

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Local Transport Strategy Draft

Contents Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Vision and performance 3. Putting our customers first 4. Sustaining a thriving city 5. Protecting our environment 6. Road safety 7. Managing and maintaining our infrastructure 8. Travel planning, travel choices and marketing 9. Active travel 10. Public transport 11. Car and motorcycle travel 12. Car parking 13. Freight 14. Edinburgh’s connectivity 15. Making it happen Appendix 1 – Our indicators Appendix 2 – Plan and programme Appendix 3 – Policy documents Appendix 4 - References 1 Foreword "A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transport." Enrique Peñalosa, one time mayor of Bogota. The last ten years have seen achievements that Edinburgh can be proud of. We are the only city in Scotland that saw seen walking, cycling and public transport all strengthen their role between the 2001 and 2011 censuses. Edinburgh now boasts the highest share of travel to work in Scotland by each of foot, cycle and bus and the highest share in the UK for bus. We have also bucked Scottish and UK trends in car ownership; despite increasing affluence, a lower percentage of Edinburgh households owned a car in 2011 than 2001. The next five years promise to be an exciting time. We have delivered the first phase of the new Tram line, and can finally enjoy all its benefits. Transport for Edinburgh will be working to deliver increased integration and co-ordination of the wider public transport network. Edinburgh is joining the growing list of progressive UK cities putting people first through applying 20mph speed limits. -

Regional Transport Strategy 2008 – 2023

Regional Transport Strategy 2008 – 2023 1 2 Chair’s Foreword As Chair of SEStran, I am proud to introduce our Regional Transport Strategy. It represents an historic first opportunity to plan for the long-term transport needs of over 1.5 million people, living in Scotland’s most economically vibrant region. In developing the strategy, we have consulted extensively with stakeholders and the public, to ensure that as wide a range of views as possible from around the region are reflected. South East Scotland needs a transportation system that is comprehensive, sustainable and inclusive. It must meet the needs of business and ensure that people living in the region can share in its prosperity. It must provide a choice of suitable transport options that will improve access to health care, education, public services and employment opportunities. It must also contribute towards reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases, and reducing the growing problem of traffic congestion. Through our Regional Transport Strategy, SEStran wants to encourage people to make smarter choices when travelling. We want them to consider a range of transport options, including; cycling and walking, making sensible use of their cars, avoiding single occupancy journeys wherever possible, and by making public transport their travel mode of choice. We are already supporting a significant programme of initiatives that offer real added value to public transport provision. In 2006-7 alone we supported over 50 infrastructure improvement projects, in partnership with local authorities. In 2007/8 we have spend an additional £15 million on projects ranging from park and ride, to bus priority schemes and improved cycle paths. -

View PDF in Full Window

For Future Council Executive DEVELOPMENT AND TRANSPORT POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND SCRUTINY PANEL FORTH REPLACEMENT CROSSING PARLIAMENTARY BILL REPORT BY TRANSPORTATION MANAGER A. PURPOSE OF REPORT John Swinney, Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Sustainable Development has recently introduced a Hybrid Bill to the Scottish Parliament to construct a Forth Replacement Crossing (FRC) and associated infrastructure. The purpose of this report is to present to the panel the benefits, opportunities and risks to West Lothian resulting from the FRC proposals. B. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended, that the panel 1. considers this report and the attached proposed response and recommends them for approval by the Council Executive. The focus of this being the potential impact of the new crossing on Newton village and a lack of adequate public transport provision; 2. recommends to the Council Executive to approve the Joint Position Statement of the new Forth crossing; 3. recommends to the Council Executive that officers be authorised to lodge an objection by the council to the Hybrid Bill at Stage 1 of the parliamentary process, to represent the interests of the council throughout that stage of the process, and to do so in partnership with SEStran and some or all of its constituent authorities if so advised; 4. notes that the SEStran Board approved a report setting out it’s position on the Hybrid Bill at it’s meeting on 4 December 2009; and 5. notes that further reports will be brought forward to advise of the outcome of Stage 1 of the parliamentary process and to seek authority for actions needed to represent the council’s interests at later stages of that process. -

Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021

Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021 1 Midlothian Midlothian Midlothian Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021 Table of Contents 1. Introduction: Purpose of the Travel Plan Page 1 2. National, Regional and Local Context Page 2 3. Aims, Objectives and Targets Page 3 4. Information Gathering Page 4 5. Programme of Action Page 5 6. Monitoring and Review Page 10 Annex A: Targets for each Travel Plan Objective Page 11 Appendix: Analysis of Responses to the Travel Questionnaire Page 13 Published by Midlothian Council April 2017 1 • Introduction: Purpose of the Travel Plan 1.1 A Travel Plan is a package of measures aimed at promoting sustainable travel within an organisation, a necessary component of which is a reduction in single occupant car trips (principally those that are part of the daily commute) as well as addressing car parking and car use in general. It also aims to make necessary car travel more sustainable. A travel plan is tailored to the specific circumstances of an organisation and the sites where it is based, taking into account factors such as current modal split, size and location of the organisation or buildings, number of staff employed, the number of visitors and the number of deliveries or contractors servicing buildings. Travel planning is not a one-off document; it is an ongoing process of organisational change, a dynamic process that grows and develops with time to reflect changes in staff and visitor characteristics and the requirements of the organisation implementing the plan. 1.2 This Travel Plan demonstrates how Midlothian Council has applied national, regional and local policy to its own operation, in support of transport policy across Scotland. -

Appendix a – Sestran Regional Model Option Assessment

Appendix A – SEStran Regional Model Option Assessment 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview 1.1.1 This Appendix describes the SEStran Regional Model (SRM) outputs for the five defined scenario option tests. The definition of these scenario options and any associated modelling assumptions is described in the MLDP Options for Appraisal Note (SYSTRA, September 2010). 1.1.2 Each scenario option is compared with the MLDP Reference Case and the SEStran Regional Model Analysis Report (SYSTRA, September 2010) provides a summary of the Midlothian LDP model analysis, which has been undertaken using the SRM. This document also includes a summary of the SRM, and the definition of the assumed MLDP land-use scenario, which is common in all the scenario option tests. 1.2 Model Dimensions 1.2.1 The SRM demand model contains 470 zones from which traffic and travel (both road and PT based) originates and destinates. Where 16 zones make up Midlothian in the demand and PT models, this is expanded to 27 zones for the road model. This allows for a better representation of the traffic movements within the Midlothian area with the inclusion of additional network detail. 1.2.2 The SRM is representative of average weekday travel movements within which the following time periods are modelled: Average weekday (AM) morning peak hour: 07:00-10:00; and Average weekday (IP) inter peak hour: 10:00-16:00; and Average weekday (PM) evening peak hour: 16:00-19:00. 1.2.3 Individual factors are applied by mode and time period to create an ‘average’ peak hour.