Regional Transport Strategy 2008 – 2023

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View A876 T Clackmannanshire Bridge

TRANSPORT SCOTLAND SCOTTISH TRUNK ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT EVALUATION 3YA Evaluation Report for A876(T) Clackmannanshire Bridge TRANSPORT SCOTLAND SCOTTISH TRUNK ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT EVALUATION 3YA Evaluation Report for A876(T) Clackmannanshire Bridge CONTENTS Page 1 SUMMARY OF IMPACTS 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Operational Indicators – How is the project operating? 2 1.3 Process Indicators – How well was the project implemented? 2 1.4 Forecasting – How accurate were predictions? 3 1.5 Objectives – Has the project met its objectives? 4 1.6 Cost to Government – Is the project delivering value for money? 4 2 INTRODUCTION 7 2.1 Background to Project Evaluation 7 2.2 This Evaluation and Project Reported 8 2.3 Previous Evaluations 9 3 PROJECT EVALUATION 13 3.1 Introduction 13 3.2 Evaluation Methodology 15 3.3 The Operation of the Project 16 3.4 Environment 24 3.5 Safety 28 3.6 Economy 33 3.7 Accessibility & Social Inclusion 34 3.8 Integration 36 3.9 Cost to Government 38 3.10 Value for Money 39 3.11 Achievement of Objectives 40 3.12 Evaluation Summary 46 A ENVIRONMENT 49 A.1 Introduction 49 A.2 Environmental Findings 50 A.3 Three-Year After Review Findings 51 B METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES 66 B.1 Overview 66 B.2 Network Traffic Indicators 66 B.3 Environmental 69 B.4 Safety 69 B.5 Economy 70 B.6 Integration 71 B.7 Accessibility & Social Inclusion 71 B.8 Costs to Government 71 B.9 Value for Money 72 B.10 Achievement of Objectives 73 TABLES Page Table 2.1: Project Summary Details 8 Table 3.1: Traffic Analysis Summary 21 Table 3.2: Travel -

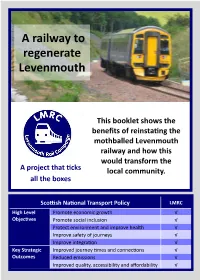

A Railway to Regenerate Levenmouth

A railway to regenerate Levenmouth This booklet shows the benefits of reinstating the mothballed Levenmouth railway and how this would transform the A project that ticks local community. all the boxes Scottish National Transport Policy LMRC High Level Promote economic growth √ Objectives Promote social inclusion √ Protect environment and improve health √ Improve safety of journeys √ Improve integration √ Key Strategic Improved journey times and connections √ Outcomes Reduced emissions √ Improved quality, accessibility and affordability √ CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Executive Summary 1 1.2 The Vision 2 1.3 The Proposal 3 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2.1 The mothballed Leven line 4 2.2 Population 6 2.3 Previous studies 8 2.4 Potential rail freight 10 2.5 Support for Levenmouth rail link 11 3. BENEFITS 3.1 Personal stories 12 3.2 What makes a good rail reopening project? 14 3.3 Delivering Scottish Government policy 15 3.4 Freight 16 3.5 Land Value Capture 17 3.6 Tourism 18 3.7 Wider economic and regional benefits 20 3.8 The business case - Benefit to Cost ratio 21 4. RE-INSTATING THE RAILWAY 4.1 Construction costs - Comparing Levenmouth with Borders 22 4.2 Timetable issues 24 4.3 Other project issues 25 5. MOVING FORWARD 5.1 Conclusions 26 5.2 The final report? 26 6. LEVENMOUTH RAIL CAMPAIGN 6.1 About our campaign 27 6.2 Our Charter 28 6.3 More information 29 - 1 - 1. Introduction 1.1 Executive Summary This booklet has been produced by the Levenmouth Rail Campaign (LMRC) with the support of a group of railway professionals who wish to lend their expertise to the campaign. -

Annual Report 2019-20

Annual Report 2019-20 Annual 19-Report 20 Annual Annual Report 2019-20 Report 2019-20 Contents 03 Foreword (Chair) 05 Who We Are 12 Our Activities 2019-20 31 European Projects 37 Appendix: Annual Accounts and Reports 38 Contact Information 2 Annual Report 2019-20 Foreword Our role providing strategic regional data and trends to produce a direction Main Issues Report. This is a precursor As a Regional Transport Partnership, to the development of a new Regional SEStran provides strategic direction. We Transport Strategy which will set out work to achieve common purpose across an ambitious course for transforming our eight local authority partners; we have transport and mobility across the region. a statutory duty to prepare a Regional Leading by example Transport Strategy (RTS) and keep it up to Last year SEStran continued to be actively date. The RTS provides the coordinating involved in demonstrating how innovative platform for the development of local changes in strategic transport, personal transport plans. It helps shape a wide mobility and logistics will work in the range of policies for regional and local south east of Scotland. land use, and economic development As Chair of SEStran, I am plans. It fosters a consistent approach Many of the projects we supported help immensely proud to present across our eight statutory partners. to tackle the most challenging issues that the annual report for 2019/20. we face today, and we have continued The challenges we now face as a region to collaborate on some of the most with a rapidly growing population, and Throughout the year, SEStran pro- innovative EU and Scottish projects in those we all face as a society from more actively developed strategies and order to bring the best of new approaches extreme weather events and climate studies, and supported projects that to our partners and region. -

SESTRAN RAIL STRATEGY From: DIRECTOR of PLANNING and ENVIRONMENT

8 .iENDA ITEM NO. ..... *3~.....-. NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: PLANNING & ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE Subject ROADS & TRANSPORTATION SUB COMMITTEE SESTRAN RAIL STRATEGY From: DIRECTOR OF PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT Date: 9" August 2000 Ref DITTI03I02ISCW 1. This report informs Committee of the development of a draft strategy in respect of future rail service provision in the South East Scotland Transport Partnership (SESTRAN) area. The approval of Committee is sought to the submission of the comments contained in this report as a response to the SESTRAN strategy. -Detail 2. The nine Councils in the South East Scotland Transport Partnership are working towards agreement on a strategy for the development of passenger rail services in the eastern central belt and the borders area. Some of the proposals relate only to the SESTRAN area but others have implications for North Lanarkshire. These latter are discussed below. 3. Edinburgh Airport Link The development of rail access served by GlasgowEdinburgh trains would open up opportunities for a direct rail connection from Cumbernauld and/or Croy to Edinburgh Airport. Edinburgh has direct flights to various other countries in Europe which are not available from Glasgow Airport. Access to Glasgow Airport itself is difficult at times because of congestion on the M8 through Glasgow city centre and the lack of a rail connection to that airport. The rail connection to Edinburgh Airport could therefore be attractive for businesses and residents in the Kilsyth and Cumbernauld area in terms of improving access to/from European destinations. 4. Edinburgh-Shotts-Glasgow Central SESTRAN propose an upgrade of the Shotts line including electrification. -

PTA Models of Organisation for Regional Transport Governance

5. Appx 1 Southeast Scotland Transport Partnership PTA models of organisation for regional transport governance Report Project No: 67751 November 16 Transport Research Institute, Edinburgh Napier University, 10 Colinton Rd Edinburgh EH10 5DT [email protected] Prepared by: TR Verified by: RL Approved by: JG Status: Confidential Issue no: 1 Date: 25/11/16 Directory & File Name: Status: Draft v2 Issue no: 1 Date: 25/11/16 C:\Users\tom\Desktop\tom1\r esearch\SEStran rts\2016\SEStran Governance Report Edinburgh Napier University TRI Nov 2016.docx Directory & File Name: C:\Documents and Settings\Tombo\My Documents\proposals\Active travel proposal v2.doc TRI Edinburgh Napier University Report for SEStran on PTA models Table of Contents 1. PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................ 2 1.1 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 REPORT STRUCTURE ......................................................................................................... 2 2. DIFFERENT FORMS OF (P)TA .............................................................................................. 2 2.1 WHAT IS A MODEL 3 REGIONAL TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIP AND HOW DOES IT DIFFER FROM WHAT SESTRAN IS NOW? ............................................................................................................... 2 2.2 CAPACITY OF RTPS IN SCOTLAND ..................................................................................... -

View PDF in Full Window

For Future Council Executive DEVELOPMENT AND TRANSPORT POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND SCRUTINY PANEL FORTH REPLACEMENT CROSSING PARLIAMENTARY BILL REPORT BY TRANSPORTATION MANAGER A. PURPOSE OF REPORT John Swinney, Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Sustainable Development has recently introduced a Hybrid Bill to the Scottish Parliament to construct a Forth Replacement Crossing (FRC) and associated infrastructure. The purpose of this report is to present to the panel the benefits, opportunities and risks to West Lothian resulting from the FRC proposals. B. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended, that the panel 1. considers this report and the attached proposed response and recommends them for approval by the Council Executive. The focus of this being the potential impact of the new crossing on Newton village and a lack of adequate public transport provision; 2. recommends to the Council Executive to approve the Joint Position Statement of the new Forth crossing; 3. recommends to the Council Executive that officers be authorised to lodge an objection by the council to the Hybrid Bill at Stage 1 of the parliamentary process, to represent the interests of the council throughout that stage of the process, and to do so in partnership with SEStran and some or all of its constituent authorities if so advised; 4. notes that the SEStran Board approved a report setting out it’s position on the Hybrid Bill at it’s meeting on 4 December 2009; and 5. notes that further reports will be brought forward to advise of the outcome of Stage 1 of the parliamentary process and to seek authority for actions needed to represent the council’s interests at later stages of that process. -

Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021

Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021 1 Midlothian Midlothian Midlothian Midlothian Council Travel Plan 2017-2021 Table of Contents 1. Introduction: Purpose of the Travel Plan Page 1 2. National, Regional and Local Context Page 2 3. Aims, Objectives and Targets Page 3 4. Information Gathering Page 4 5. Programme of Action Page 5 6. Monitoring and Review Page 10 Annex A: Targets for each Travel Plan Objective Page 11 Appendix: Analysis of Responses to the Travel Questionnaire Page 13 Published by Midlothian Council April 2017 1 • Introduction: Purpose of the Travel Plan 1.1 A Travel Plan is a package of measures aimed at promoting sustainable travel within an organisation, a necessary component of which is a reduction in single occupant car trips (principally those that are part of the daily commute) as well as addressing car parking and car use in general. It also aims to make necessary car travel more sustainable. A travel plan is tailored to the specific circumstances of an organisation and the sites where it is based, taking into account factors such as current modal split, size and location of the organisation or buildings, number of staff employed, the number of visitors and the number of deliveries or contractors servicing buildings. Travel planning is not a one-off document; it is an ongoing process of organisational change, a dynamic process that grows and develops with time to reflect changes in staff and visitor characteristics and the requirements of the organisation implementing the plan. 1.2 This Travel Plan demonstrates how Midlothian Council has applied national, regional and local policy to its own operation, in support of transport policy across Scotland. -

Appendix a – Sestran Regional Model Option Assessment

Appendix A – SEStran Regional Model Option Assessment 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview 1.1.1 This Appendix describes the SEStran Regional Model (SRM) outputs for the five defined scenario option tests. The definition of these scenario options and any associated modelling assumptions is described in the MLDP Options for Appraisal Note (SYSTRA, September 2010). 1.1.2 Each scenario option is compared with the MLDP Reference Case and the SEStran Regional Model Analysis Report (SYSTRA, September 2010) provides a summary of the Midlothian LDP model analysis, which has been undertaken using the SRM. This document also includes a summary of the SRM, and the definition of the assumed MLDP land-use scenario, which is common in all the scenario option tests. 1.2 Model Dimensions 1.2.1 The SRM demand model contains 470 zones from which traffic and travel (both road and PT based) originates and destinates. Where 16 zones make up Midlothian in the demand and PT models, this is expanded to 27 zones for the road model. This allows for a better representation of the traffic movements within the Midlothian area with the inclusion of additional network detail. 1.2.2 The SRM is representative of average weekday travel movements within which the following time periods are modelled: Average weekday (AM) morning peak hour: 07:00-10:00; and Average weekday (IP) inter peak hour: 10:00-16:00; and Average weekday (PM) evening peak hour: 16:00-19:00. 1.2.3 Individual factors are applied by mode and time period to create an ‘average’ peak hour. -

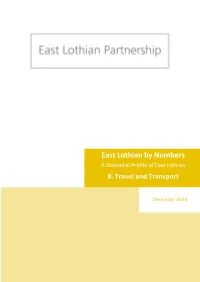

East Lothian by Numbers

East Lothian by Numbers A Statistical Profile of East Lothian 8. Travel and Transport December 2016 Transport and Travel Table of Contents Introduction and Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 SIMD Access Domain ................................................................................................................................ 2 Main Mode of Travel ................................................................................................................................ 3 Public Transport ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Buses………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Rail .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Active and Sustainable Travel ................................................................................................................... 8 Travel to Work ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Travel to Study ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Travel to Nursery and School ................................................................................................................. -

Partnership Board Meeting Friday 19Th June 2020 Item B2

Partnership Board Meeting Friday 19th June 2020 Item B2. Consultation Responses Consultation Responses 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This report provides the Members of the Board with an update on the consultations SEStran has responded to. 2. City of Edinburgh Council – City Plan 2030 and City Mobility Plan 2.1 SEStran responded to the joint consultation on the City of Edinburgh Council’s City Plan 2030 (Local Development Plan) and City Mobility Plan. Given that the two plans are inextricably linked, a single response was submitted in addition to online responses to both questionnaires. The full response is attached to this report in item B2.2. 3.1 Recommendation The Board is asked to note the terms of the consultation response. Julie Vinders Project Officer 11 June 2020 Appendix: • Item B2.1 City Plan 2030 and City Mobility Plan – SEStran response 30th April 2020 Item B2.1 City of Edinburgh Council – City Plan 2030 and City Mobility Plan SEStran response 30th April 2020 City of Edinburgh Council: City Plan 2030 and City Mobility Plan Consultation SEStran response – v.1 Introduction SEStran welcomes the concurrent development of the City of Edinburgh Council’s City Mobility Plan and City Plan 2030 (Local Development Plan). SEStran believes that their parallel 2030 horizon brings opportunities to align development and much more efficient use of transport systems. SEStran notes that both draft plans could do more to clearly demonstrate integrated thinking, and ensure the interdependencies between them is made more explicit. As with SEStran’s view that these two plans are inextricably linked, this is a single response in addition to online responses to both questionnaires. -

Efficient Operations and Sustainable Design / Sestran Maid of the Forth

SEStran Report: Seafari (Maid of the Forth) North Berwick Fuel Trials This document is part of iTransfer, a North Sea Region Interreg programme project, which is funded by the European Regional Development Fund. iTransfer (Innovative Transport Solutions for Fjords, Estuaries and Rivers) aims to make ferry transport more freely accessible and sustainable, and encourage more people to travel by water. In areas in the North Sea Region (NSR) there are opportunities to replace existing vehicle routes with passenger ferries as a viable alternative. Travelling by ferry is more sustainable, easier and quicker. It can also provide lifeline services to remote communities. For more information visit www.itransferproject.eu iTransfer – Seafari (Maid of the Forth) North Berwick Report 2 SEStran, Ground Floor, Claremont House, 130 East Claremont Street, Edinburgh EH7 4LB T: +44 (0)131 524 5150 F: +44 (0)131 524 5151 E: [email protected] www.sestran.gov.uk www.iTransfer.eu Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 Background/challenge ................................................................................................................... 4 Activity/method ........................................................................................................................... -

Sestran Halcrow Group Limited

SEStran Edinburgh Orbital Bus Project STAG 1 Environmental Report July 2008 Halcrow Group Limited SEStran Edinburgh Orbital Bus Project STAG 1 Environmental Report July 2008 Halcrow Group Limited Halcrow Group Limited 16 Abercomby Place Edinburgh EH3 6LB Tel +44 (0)131 272 3300 Fax +44 (0)131 272 3301 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client, Perth and Kinross Council, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2008 SEStran Edinburgh Orbital Bus Project STAG 1 Environmental Report Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Signed 1 1 Draft 01/04/08 MR 2 Final Draft 01/04/08 AS 3 Updated Following Client 25/07/08 MR Comments Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Route Description 1 1.3 Planning Context 3 1.4 Option Appraisal 3 2 Methodology 4 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 The Identification of Baseline Conditions 4 2.3 The Assessment Process 5 3 Baseline Information 7 3.1 Site Location 7 4 Section 1: Wallyford Park & Ride to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary 19 4.1 Introduction 19 4.2 Summary of Environmental Impacts 23 4.3 Summary of Performance against the Planning Objectives 24 5 Section 2: Edinburgh Royal Infirmary to Straiton Park & Ride 25 5.1 Introduction 25 5.2 Summary of Environmental Impacts 29 5.3 Summary of Performance against the Planning Objectives 30 6 Section 3: Straiton Park & Ride to Hermiston