Evidence from Stamford Hill Hasidic Yiddish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

ESPERANTO: ITS ORIGINS and EARLY HISTORY 1. the First Book

Published in: Prace Komisji Spraw Europejskich PAU. Tom II, pp. 39–56. Ed. Andrzej Pelczar. Krak´ow:Polska Akademia Umieje˛tno´sci, 2008, 79 pp. pau2008 CHRISTER KISELMAN ESPERANTO: ITS ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY Abstract. We trace the development of Esperanto prior to the publi- cation of the first book on the language in 1887 and try to explain its origins in a multicultural setting. Influences on Esperanto from several other languages are discussed. The paper is an elaborated version of parts of the author’s lec- ture in Krak´owat the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, Polska Akademia Umieje˛tno´sci, on December 6, 2006. 1. The first book on Esperanto and its author The first book on Esperanto (Dr speranto 1887a) was published in Warsaw in the summer of 1887, more precisely on July 14 according to the Julian calendar then in use (July 26 according to the Gregorian calendar). It was a booklet of 42 pages plus a folding sheet with a list of some 900 morphemes. It was written in Russian. Soon afterwards, a Polish version was published, as well as a French and a German version, all in the same year (Dr. Esperanto 1887b, 1887c, 1887d). The English version of the book appeared two years later, in 1889, as did the Swedish version. The author of the book was only 27 years old at the time. His complete name, as it is known now, was Lazaro Ludoviko Zamenhof, registered by the Russian authorities as Lazar~ Markoviq Zamengof (Lazar0 Markoviˇc Zamengof00). His given name was Elieyzer in Ashkenazic Hebrew, Leyzer in Yiddish, and Lazar~ (Lazar0) in Russian. -

Estonian Yiddish and Its Contacts with Coterritorial Languages

DISSERT ATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU 2000 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES Eesti jidiš ja selle kontaktid Eestis kõneldavate keeltega ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU UNIVERSITY PRESS Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University o f Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Dissertation is accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in general linguistics) on December 22, 1999 by the Doctoral Committee of the Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu Supervisor: Prof. Tapani Harviainen (University of Helsinki) Opponents: Professor Neil Jacobs, Ohio State University, USA Dr. Kristiina Ross, assistant director for research, Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn Commencement: March 14, 2000 © Anna Verschik, 2000 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr. 53 ...Yes, Ashkenazi Jews can live without Yiddish but I fail to see what the benefits thereof might be. (May God preserve us from having to live without all the things we could live without). J. Fishman (1985a: 216) [In Estland] gibt es heutzutage unter den Germanisten keinen Forscher, der sich ernst für das Jiddische interesiere, so daß die lokale jiddische Mundart vielleicht verschwinden wird, ohne daß man sie für die Wissen schaftfixiert -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Knessia Gedolah Diary

THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN 0021-6615) is published monthly, in this issue ... except July and August, by the Agudath lsrael of Ameri.ca, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. The Sixth Knessia Gedolah of Agudath Israel . 3 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Subscription Knessia Gedolah Diary . 5 $9.00 per year; two years, $17.50, Rabbi Elazar Shach K"ti•?111: The Essence of Kial Yisroel 13 three years, $25.00; outside of the United States, $10.00 per year Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky K"ti•?111: Blessings of "Shalom" 16 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. What is an Agudist . 17 Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman K"ti•?111: RABBI NISSON WotP!N Editor An Agenda of Restraint and Vigilance . 18 The Vizhnitzer Rebbe K"ti•'i111: Saving Our Children .19 Editorial Board Rabbi Shneur Kotler K"ti•'i111: DR. ERNST BODENHEIMER Chairman The Ability and the Imperative . 21 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Helping Others Make it, Mordechai Arnon . 27 JOSEPH FRJEDENSON "Hereby Resolved .. Report and Evaluation . 31 RABBI MOSHE SHERER :'-a The Crooked Mirror, Menachem Lubinsky .39 THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not Discovering Eretz Yisroel, Nissan Wolpin .46 assume responsibility for the Kae;hrus of any product or ser Second Looks at the Jewish Scene vice advertised in its pages. Murder in Hebron, Violation in Jerusalem ..... 57 On Singing a Different Tune, Bernard Fryshman .ss FEB., 1980 VOL. XIV, NOS. 6-7 Letters to the Editor . • . 6 7 ___.., _____ -- -· - - The Jewish Observer I February, 1980 3 Expectations ran high, and rightfully so. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions

2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL Schedule of Grants Made to Grants Various Philanthropic Institutions American Folk Art Museum 127,350 American Friends of the College of American Friends of Agudat Shetile Zetim, Inc. 10,401 Management, Inc. 10,000 [ Year ended June 30, 2011 ] American Friends of Aish Hatorah - American Friends of the Hebrew University, Inc. 77,883 Western Region, Inc. 10,500 American Friends of the Israel Free Loan American Friends of Alyn Hospital, Inc. 39,046 Association, Inc. 55,860 ORGANIZATION AMOUNT All 4 Israel, Inc. 16,800 American Friends of Aram Soba 23,932 American Friends of the Israel Museum 1,053,000 13 Plus Chai, Inc. 82,950 Allen-Stevenson School 25,000 American Friends of Ateret Cohanem, Inc. 16,260 American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic 52nd Street Project, Inc. 125,000 Alley Pond Environmental Center, Inc. 50,000 American Friends of Batsheva Dance Company, Inc. 20,000 Orchestra, Inc. 320,850 A.B.C., Inc. of New Canaan 10,650 Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, Inc. 44,950 The American Friends of Beit Issie Shapiro, Inc. 70,910 American Friends of the Jordan River A.J. Muste Memorial Institute 15,000 Alliance for Children Foundation, Inc. 11,778 American Friends of Beit Morasha 42,360 Village Foundation 16,000 JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. d/b/a Harlem Stage 125,000 Alliance for School Choice, Inc. 25,000 American Friends of Beit Orot, Inc. 44,920 American Friends of the Old City Cheder in Abingdon Theatre Company 30,000 Alliance for the Arts, Inc. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) SH EVI’I SHEL PESACH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Shevi’i Shel Pesach – Kerias Yam Suf Walking on Dry Land Even in the Sea “And Bnei Yisrael walked on dry land in the sea” (Shemos 14:29) How can you walk on dry land in the sea? The Noam Elimelech , in Likkutei Shoshana , explains this contradictory-sounding pasuk as follows: When Bnei Yisrael experienced the Exodus and the splitting of the sea, they witnessed tremendous miracles and unbelievable wonders. There are Tzaddikim among us whose h earts are always attuned to Hashem ’s wonders and miracles even on a daily basis; they see not common, ordinary occurrences – they see miracles and wonders. As opposed to Bnei Yisrael, who witnessed the miraculous only when they walked on dry land in the sp lit sea, these Tzaddikim see a miracle as great as the “splitting of the sea” even when walking on so -called ordinary, everyday dry land! Everything they experience and witness in the world is a miracle to them. This is the meaning of our pasuk : there are some among Bnei Yisrael who, even while walking on dry land, experience Hashem ’s greatness and awesome miracles just like in the sea! This is what we mean when we say that Hashem transformed the sea into dry land. Hashem causes the Tzaddik to witness and e xperience miracles as wondrous as the splitting of the sea, even on dry land, because the Tzaddik constantly walks attuned to Hashem ’s greatness and exaltedness. -

Shabbos Secrets - the Mysteries Revealed

Translated by Rabbi Awaharn Yaakov Finkel Shabbos Secrets - The Mysteries Revealed First Published 2003 Copyright O 2003 by Rabbi Dovid D. Meisels ISBN: 1-931681-43-0 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise, withour prior permission in writing from both the copyright holder and publisher. C<p.?< , . P*. P,' . , 8% . 3: ,. ""' * - ;., Distributed by: Isreal Book Shop -WaUvtpttrnn 501 Prospect Street w"Jw--.or@r"wn owwv Lakewood NJ 08701 Tel: (732) 901-3009 Fax: (732) 901-4012 Email: isrbkshp @ aol.com Printed in the United States of America by: Gross Brothers Printing Co., Inc. 3 125 Summit Ave., Union City N.J. 07087 This book is dedicated to be a source of merit in restoring the health and in strengthening 71 Tsn 5s 3.17 ~~w7 May Hashem send him from heaven a speedy and complete recovery of spirit and body among the other sick people of Israel. "May the Zechus of Shabbos obviate the need to cry out and may the recovery come immediately. " His parents should inerit to have much nachas from him and from the entire family. I wish to express my gratitude to Reb Avraham Yaakov Finkel, the well-known author and translator of numerous books on Torah themes, for his highly professional and meticulous translation from the Yiddish into lucid, conversational English. The original Yiddish text was published under the title Otzar Hashabbos. My special appreciation to Mrs. -

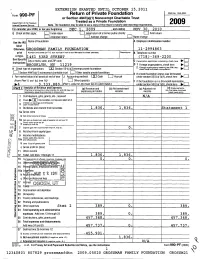

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

On the Frontier Between Eastern and Western Yiddish: Sources from Burgenland

European Journal of Jewish Studies 11 (2017) 130–147 brill.com/ejjs On the Frontier between Eastern and Western Yiddish: Sources from Burgenland Lea Schäfer* Abstract Burgenland, the smallest state of current Austria, located on the border with Hungary, once had seven vibrant Jewish communities under the protection of the Hungarian Eszterházy family. There is next to nothing known about the Yiddish variety spoken in these communities. This article brings together every single piece of evidence of this language to get an impression of its structure. This article shows that Yiddish from Burgenland can be integrated into the continuum between Eastern and Western Yiddish and is part of a gradual transition zone between these two main varieties. Keywords Yiddish dialectology and phonology – Jews in Austria and Hungary – Eastern and Western Yiddish transition zone Burgenland, the smallest state of Austria today, located on the border with Hungary, once had seven vibrant Jewish communities that stood under the protection of the Hungarian Eszterházy family. There is next to nothing known about the Yiddish variety spoken in these communities. Its geographical posi- tion, however, makes Burgenland interesting for Yiddish dialectology. As Dovid Katz has postulated, it is on the southern end of a transition zone between Eastern and Western Yiddish.1 This article will show that Yiddish * I would like to thank Jeffrey Pheiff, Oliver Schallert and Ricarda Scherschel for checking my English. I also want to thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments. 1 Dovid Katz, “Zur Dialektologie des Jiddischen,” in Dialektologie: Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung 1.2., eds. -

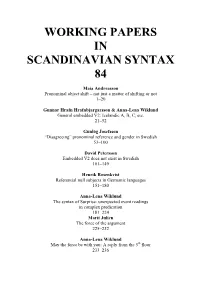

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 84

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 84 Maia Andreasson Pronominal object shift – not just a matter of shifting or not 1–20 Gunnar Hrafn Hrafnbjargarsson & Anna-Lena Wiklund General embedded V2: Icelandic A, B, C, etc. 21–52 Gunlög Josefsson “Disagreeing” pronominal reference and gender in Swedish 53–100 David Petersson Embedded V2 does not exist in Swedish 101–149 Henrik Rosenkvist Referential null subjects in Germanic languages 151–180 Anna-Lena Wiklund The syntax of Surprise: unexpected event readings in complex predication 181–224 Marit Julien The force of the argument 225–232 Anna-Lena Wiklund May the force be with you: A reply from the 5th floor 233–236 Preface Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is a publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. Due to the nature of the papers as working papers, we only print a limited number of extra copies of each volume. As a result, we do not offer any offprints of papers published in WPSS. The articles published in WPSS are also available over the net; you will find a link on the following site: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/ The 85th volume of WPSS will be published in June 2010. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than April 15, 2010. Christer Platzack editor Address Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax c/o Christer Platzack Center of Language and Literature Box 201 SE-221 00 Lund Sweden General Embedded V2: Icelandic A, B, C, etc.1 Gunnar Hrafn Hrafnbjargarson2 & Anna-Lena Wiklund3 Abstract On the basis of data from Icelandic, this paper hypothesizes that pure GV2 languages do not exist.