Houdini: a Magician Among the Spirits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osu1199254932.Pdf (640.26

FROM MUSE TO MILITANT: FRANCOPHONE WOMEN NOVELISTS AND SURREALIST AESTHETICS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary Anne Harsh, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Danielle Marx-Scouras, Advisor Professor Karlis Racevskis ______________________________ Advisor Professor Sabra Webber French and Italian Graduate Program ABSTRACT In 1924, André Breton launched the Surrealist movement in France with his publication of Manifeste du surréalisme. He and his group of mostly male disciples, prompted by the horrors of World War I, searched for fresh formulas for depicting the bizarre and inhumane events of the era and for reviving the arts in Europe, notably by experimenting with innovative practices which included probing the unconscious mind. Women, if they had a role, were viewed as muses or performed only ancillary responsibilities in the movement. Their participation was usually in the graphic arts rather than in literature. However, in later generations, francophone women writers such as Joyce Mansour and Suzanne Césaire began to develop Surrealist strategies for enacting their own subjectivity and promoting their political agendas. Aside from casual mention, no critic has formally investigated the surreal practices of this sizeable company of francophone women authors. I examine the literary production of seven women from three geographic regions in order to document the enduring capacity of surrealist practice to express human experience in the postcolonial and postmodern era. From the Maghreb I analyze La Grotte éclatée by Yamina Mechakra and L'amour, la fantasia by Assia Djebar, and from Lebanon, L'Excisée by Evelyne Accad. -

Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701

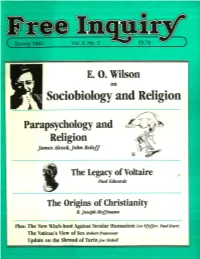

LmAA_____., Fir ( Spring 1985 E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Parapsychology and Religion James Alcock, John Beloff The Legacy of Voltaire Paul Edwards The Origins of Christianity R. Joseph Hoffmann Plus: The New Witch-hunt Against Secular Humanism Leo Pfeffer, Paul Kurtz The Vatican's View of Sex Robert Francoeur Update on the Shroud of Turin joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701 VOL. 5, NO. 2 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES 10 Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell 11 The Vatican's View of Sex: The Inaccurate Conception Robert T. Francoeur 15 An Interview with E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Jeffrey Saver RELIGION AND PARAPSYCHOLOGY 25 Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock 36 Science, Religion and the Paranormal John Beloff 42 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part I) Paul Edwards 50 The Origins of Christianity: A Guide to Answering Fundamentalists R. Joseph Hoffmann BOOKS 57 Humanist Solutions Vern Bullough 58 Doomsday Environmentalism and Cancer Rodger Pirnie Doyle 59 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Gordon Stein, Lee Nisbet, Steven L. Mitchell, Doris Doyle Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director, -

The 'World of the Infinitely Little'

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The 'world of the infinitely little': connecting physical and psychical realities circa 1900 AUTHORS Noakes, Richard JOURNAL Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part A DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 December 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/41635 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication THE ‘WORLD OF THE INFINITELY LITTLE’: CONNECTING PHYSICAL AND PSYCHICAL REALITIES IN BRITAIN C. 1900 RICHARD NOAKES I: INTRODUCTION In 1918 the ageing American historian Henry Adams recalled that from the 1890s he had received a smattering of a scientific education from Samuel Pierpont Langley, the eminent astrophysicist and director of the Smithsonian Institution. Langley managed to instil in Adams his ‘scientific passion for doubt’ which undoubtedly included Langley’s sceptical view that all laws of nature were mere hypotheses and reflections of the limited and changing human perspective on the cosmos.1 Langley also pressed into the hands of his charge several works challenging the supposedly robust laws of ‘modern’ physics.2 These included the notorious critiques of mechanics, J. B. Stallo’s Concepts and Theories of Modern Physics (1881) [AND] Karl Pearson’s Grammar of Science (1892), and several recent numbers of the Smithsonian Institution’s -

Modernscience

386 Book Reviews Modern Science Annette Müllberger (ed.) Los límites de la ciencia. Espiritismo, hipnotismo y el estudio de los fenómenos para- normales (1850–1930). Madrid: Consejo superior de investigaciones científicas, 2016, 346 pp., 30€, ISBN: 978-84-00-10053-7. In the last few years, the history of science has been showing a particular inter- est in the field of psychical research, metapsychics and all that today is defined as parapsychology. The works of historians of science like Ruth Brandon, John Cerullo, Alex Owen and most recently those of Sofie Lachapelle, Régine Plas, Christine Blondel, Heather Wolffram and Andreas Sommer, only to name a few, have overcome the initial historians’ mistrust towards to this complex and var- iegated range of phenomena, thus considering it as a proper epistemic object. Less rigid definitions of “science” and “rationality” have been provided, which have called into question the structure of an allegedly real and objective knowl- edge. Even the debate among those who declared themselves interested in rethinking and expanding the limits of science and those who, on the contrary, were claiming that the study of the paranormal should be left out from the def- inition of “science”, has become the subject of these investigations of historical nature. Science is indubitably the result of a complex process. The outcome of this process is a totality of statements about reality that calls for trust and faith. Science creates convictions and beliefs. Spiritualism wished to generate convictions too, and the believer who welcomed such convictions found itself part of the epistemological process of creation of belief, in addition to being receptor of the “truths” in question. -

Christopher Hartney

OF SEANCE AND SURREALISM, POETRY AND CRISIS Christopher Hartney When asked by a bureaucrat what purpose poetry served a nation, A. D. Hope quipped that it justifies its existence. This might seem an exuberant claim, but in conservative titnes it is sometimes hard to discern the value to society of the poetic quest. 1 This paper is an examination of that period between the Great War and the onset of the Great Depression when poetry became a centre of certainty in the lives of those lost in the maelstrom of the times. It may be a broad comparison to draw, but I have chosen to look at Vietnam and its colonial master of the period, France. It is in the t\venties that these two nations became the focal point for two highly influential social movements that sought to revi vify not just national existence but the human spirit. In France this revitalisation was effected via the movement kno\vn as surrealism. Clearly it was a secular movement, and yet its poetic quest had much in common \vith religious developments bursting onto the scene in Vietnam at the same time; in particular a new religious movement called Caodaism. The twenties were crucible years; after the Great War, many assumptions about life and civilisation had to be rethought. In France, Surrealism would create a vital social space \vithin which this rethinking could take place. Artistically, Surrealism's primary source of influence was Dada, but Surrealists also couched the movement's heritage I For example, a current indication of the place of poetry in Australia, Rosanna 1Y1cGlone-Healy writes in the Sydney fl;lorning Herald, 29-30 Septelnber 200 I (Spectrum 6) 'The support for literature is smalL and the place of poetry in the national psyche is negligible.' 355 CHRIS HARTNEY as coming from the growing scientific tradition of psychoanalysis. -

Prophetess of the Spirits: Mother Leaf Anderson and the Black Spiritual Churches of New Orleans

SIXTEEN Prophetess of the Spirits Mother Leaf Anderson and the Black Spiritual Churches of New Orleans Yvonne Chireau Mother Leaf Anderson, a thirty-two-year-old missionary, preacher, and proph etess, went to New Orleans, Louisiana, in 19 ig to establish a church that would reflect her distinctive vision of sacred reality. In 1927, when she died, she left a legacy of women’s leadership and spiritual innovation that had transformed the religious landscape of the city for both blacks and whites. Anderson, a woman of African and Native American ancestry, founded a religion that would carry her signature into the present day. Leaf Anderson’s role in the formation of the New Orleans black Spiritual churches reveals the unusual and complex cultural configurations that she embodied in both her life and her ministry. The ways that she redefined gender and religious empower ment for women in the Spiritual tradition influenced all who came after her. This essay considers gender and race as intersecting categories in its analy sis of the churches established by Anderson, a network of congregations that synthesized elements of Protestantism, Catholicism, nineteenth-century American spiritualism, and neo-African religions. My focus on African Amer ican women serves as a counterbalance to interpretations of religious his tory that fail to account for race, class, and gender as determinants of female subjectivity. The contrasting social and cultural realities for black and white women underscore the differences in the religious options that both groups have historically sought and chosen. The black Spiritual movement is one product of those differences. -

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics This volume examines the relationship between occultism and Surrealism, specif- ically exploring the reception and appropriation of occult thought, motifs, tropes and techniques by surrealist artists and writers in Europe and the Americas from the 1920s through the 1960s. Its central focus is the specific use of occultism as a site of political and social resistance, ideological contestation, subversion and revolution. Additional focus is placed on the ways occultism was implicated in surrealist dis- courses on identity, gender, sexuality, utopianism and radicalism. Dr. Tessel M. Bauduin is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Dr. Victoria Ferentinou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ioannina. Dr. Daniel Zamani is an Assistant Curator at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Are you really Syrious?, 1953. Oil on three-ply. Collection of Miguel S. Escobedo. © 2017 Estate of Leonora Carrington, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2017. This page intentionally left blank Surrealism, Occultism and Politics In Search of the Marvellous Edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani First published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis The right of Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Mediums, Spirits, and Spooks in the Rocky Mountains: a Brief History of Spiritualism in Colorado 1860-1950

Mediums, Spirits, and Spooks in the Rocky Mountains: A Brief History of Spiritualism in Colorado 1860-1950. “Scarcely another cultural phenomenon affected as many people or stimulated as much interest as did Spiritualism in the ten years before the Civil War and, for that matter, throughout the subsequent decades of the nineteenth century…. ‘in 1856, it seemed more likely that Spiritualism would become the religion of America than in 156 that Christianity would become the religion of the Roman Empire, or in 756 that Mohammedanism would be that of the Arabian population.’”1 Introduction During the second half of the nineteenth-century, the country was swept off of its feet by spiritualistic phenomena. Broadly defined, Spiritualism is the belief that the dead survive as spirits and can communicate with the living through the use of mediums or people with a special otherworldly perceptiveness or sensitivity that enables them to detect the presence of and communicate with spirits. Although documented happenings of otherworldly communication and paranormal phenomena have occurred around the world since the beginnings of written history, it was not until the year 1848, with the emergence of organized Spiritualism in the United States, that communication between the living and dead necessitated the assistance of a medium.2 The development of this Modern Spiritualism (the version that requires a medium) began in 1848 with the Fox sisters in Hydesville, New York. After the “Hydesville episode” of 1848, Spiritualism rapidly spread throughout the rest of the United States, starting a very popular trend that appealed to politicians of great import, quintessential authors, the elite of society, and the under classes alike. -

A Genealogy of the Extraterrestrial in American Culture

The Extraterrestrial in US Culture by Mark Harrison BA Indiana University 1989 MA University of Pittsburgh 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY 0F PITTSBURGH Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Mark Harrison It was defended on April 3, 2006 and approved by Jonathan Arac Bill Fusfield Jonathan Sterne Dissertation Director: Carol Stabile ii The Extraterrestrial in US Culture Mark Harrison, PhD University of Pittsburgh This dissertation provides a cultural analysis of the figure of the extraterrestrial in US culture. The sites through which the extraterrestrial appears -- spiritualism, so-called “space brother” religions, unidentified flying objects, and alien abduction -- are understood as elements of an ongoing displaced utopian imaginary. This mode of utopian thought is characterized by recourse to figures of radical alterity (spirits of the dead, “ascended masters,” and the gray) as agents of radical social change; by its homologies with contemporaneous political currents; and through its invocation of trance states for counsel from the various others imagined as primary agents of change. Ultimately, the dissertation argues that the extraterrestrial functions as the locus both for the resolution of tensions between the spiritual and the material and for the projection of a perfected subject into a utopian future. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction …………………………………………… 1 A. A Study in Gray………………………..……. ………...1 B. Material/Ethereal…………..………………………….. 7 C. The Inappropriate/d Other……..……………………... 10 D. Dream, Myth, Utopia……………… …..………….. 14 E. Chapters…………………………..……… ………... 18 II. Chapter 1: The Dead…………………………………. 21 A. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.1: a - D

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.1: A - D © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E27 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.1: A - D Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

A Willing Suspension of Disbelief: Victorian Reactions to the Spiritualist Phenomena by Candace Gregory

A Willing Suspension of Disbelief: Victorian Reactions to the Spiritualist Phenomena by Candace Gregory "The First fact We're taught is, there's a world beside this world, With spirits, not mankind, for tenantry." <1> It would not be terribly difficult for a modern critic to dismiss the spiritualist movement of the late nineteenth century as a "monstrous folly" (as one Victorian described it), or as an aberration in what is normally viewed as a serious and generally solemn period in the modern history of England. < 2> Spiritualism was an attempt by the late Victorians to communicate with the spirits of the dead, hoping to prove continued existence after physical death and to gather some information on first hand experiences of it. There were certainly some elements of folly and naivete in the audience that willingly flocked to the presentations of the mediums, some of which were undoubtedly performers of the most unscrupulous kind. With equal certainty, there were contemporary Victorians that would have agreed with such a view. However, this attitude belittles the Victorian spiritualists in general, many of whom had very serious intentions and sincere motives. Additionally, the spiritualist phenomena incorporated many of the fascinating general aspects that could be found in any study of the Victorian culture; spiritualism is an excellent focal point from which the various dynamics inherent in the Victorian society can be examined and understood. These dynamics are so varied and often even conflicting in their manifestation in the spiritualist phenomena that it is difficult to define the movement's experiences with any degree of precision. -

Salt Over the Shoulder: a Guide to the Supernatural in the Modern World Chloe N

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 Salt over the shoulder: a guide to the supernatural in the modern world Chloe N. Clark Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Chloe N., "Salt over the shoulder: a guide to the supernatural in the modern world" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15138. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15138 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Salt over the shoulder: A guide to the supernatural in the modern world by Chloe N. Clark A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: Debra Marquart, Major Professor Charissa Menefee Jeremy Withers Christina Gish Hill Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Chloe N. Clark, 2016. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv INTRODUCTION 1 EDITOR’S NOTE 4 Other Forms of Conjuring the Moon 5 SECTION ONE: CLEANSINGS 6 Stages of the Exorcism 8 Play Darkness 9 the 4 stages of possession