GAO-09-580 April 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Are Digital Trends Reshaping Government Financial Organizations? Findings from Deloitte NASACT 2015 Digital Government Transformation Survey

How are digital trends reshaping government financial organizations? Findings from Deloitte NASACT 2015 Digital Government Transformation Survey A publication of Deloitte and the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers (NASACT) Message from NASACT Findings from the Deloitte NASACT 2015 Digital Government Transformation Survey of US state and local financial government executives help shed light on the state of digital transformation in government. A total of 33 NASACT members, with diverse functional and organizational backgrounds, participated in the survey. This is a subset of Deloitte’s Global Digital Government Transformation Survey that covered 1,205 public sector executives across 70+ countries during January and February 2015. The survey explores how digital transformation is reshaping state and local governments. It seeks to understand what strategies government organizations are using to navigate the digital roadmap and to identify the areas of greatest opportunity in adapting a digital-first strategy. The organizations have to recognize that digital transformation is not just about implementing digital technologies. They have to create a strategic plan to best implement a digital transformation by taking into consideration a number of issues, such as: • How does the culture of an organization impact digital transformation? • Do leaders and workforces have sufficient skills and resources to successfully achieve digital transformation? • What procurement processes are in place to provide much-needed flexibility to design and develop digital services? Not surprisingly, many organizations recognize hurdles to manage the digital transition in all of these areas. At least two-thirds of the organizations find it challenging to manage digital transition in each — culture, leadership, workforce, and procurement. -

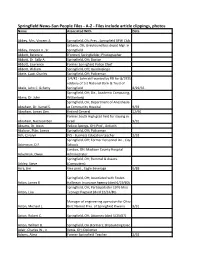

Springfield News-Sun People Files - A-Z - Files Include Article Clippings, Photos Name Associated with Date

Springfield News-Sun People Files - A-Z - Files include article clippings, photos Name Associated With Date Abbey, Mrs. Vincent A. Springfield, Oh; Pres., Springfield BPW Club Urbana, OH; Greyhound bus depot Mgr. in Abbey, Vincent A., Sr. Springfield Abbott, Berenice (Former) Springfielder; Photographer Abbott, Dr. Sally A. Springfield, OH; Doctor Abbott, Lawrence Former Springfield Police Chief Abbott, William Springfield, OH; Quadraplegic Abele, Capt. Charles Springfield, OH; Policeman 1/4/42 - John still wanted by FBI for 8/1935 robbery of 1st National Bank & Trust of Abele, John C. & Betty Springfield 8/29/35 Springfield, OH; Dir., Academic Computing, Abma, Dr. John Wittenberg Springfield, OH; Department of Anesthesia Abraham, Dr. Kamel S. at Community Hospital 9/93 Abraham, James Gen. Retired General 12/90 Former South High grad held for slaying in Abraham, Nachson Ben Israel 9/91 Abrams, Dr. Irwin Yellow Springs, OH; Prof., Antioch Abshear, Ptlm. James Springfield, OH; Policeman Ach, Carolyn JVS - Business Education teacher 2/93 Springfield, OH; Former Personnel Dir., City Ackerman, D.F. Schools London, OH; Madison County Hospital Ackerman, Owen Administrator Springfield, OH; Rummel & Assocs. Ackley, Steve (Computers) Acra, Jim Vice presi., Eagle Beverage 6/88 Springfield, OH; Associated with Foster- Acton, James R. Hallinean Insurance Agency (died 6/19/80) Springfield, OH; Participated in 1976 Miss Acton, Lisa Teenage Pageant (died 12/24/80) Manager of engineering operation for Ohio Acton, Michael L. Bell; Named Pres. of Springfield Kiwanis 9/91 Acton, Robert C. Springfield, OH; Attorney (died 5/25/87) Acton, William B. Springfield, OH (Former); Shipbuilding Exec. Adair, Charles W., Jr. -

County of Greene, Ohio

County of Greene, Ohio 2019 Annual Information Statement in connection with Bonds, Notes and Certificates of Indebtedness of the County This Annual Informational Statement pertains to the operations of Greene County for the calendar year 2018 (where possible, 2019 data has been provided). In addition to providing information on an annual basis, the County of Greene intends that this Statement will be used, together with information to be specifically provided by the County for that purpose, in connection with the original offering and issuance by the County of its bonds, notes and certificates of indebtedness. Questions regarding information contained in this Annual Information Statement should be directed to David A. Graham, Greene County Auditor, Greene County Office Building, 69 Greene Street, Xenia, Ohio 45385. The date of this Annual Information Statement is September 1, 2019. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT ................................................................................................ 1 GREENE COUNTY, OHIO ........................................................................................................... 2 County Government .................................................................................................................. 2 General Government ........................................................................................................... 3 Administration of Justice System ....................................................................................... 4 County-owned -

Oml Updates: At-A-Glance

OML UPDATES: AT-A-GLANCE Here are the top three things you need to know this week: 13 states so far, including Texas and Ohio, have passed laws this year dictating how cities should regulate small cell wireless technology. In addition to the cities in Ohio that have filed suit, 22 Texas cities are also legally challenging their state's law. Ohio is making money off of its Medicaid expansion. This budget year, Ohio is receiving $62.2 million more than it currently spends on Medicaid expansion. Net revenue projections for next year hit $21.2 million. In total, the state uses Medicaid expansion money to leverage over $300 million in additional revenue each year. Ohio transportation by the numbers: since 2012, 31 states have enacted a transportation funding increase; 8 states have raised gas taxes, and 10 states have approved new fees for electric and/or hybrid vehicles. October 13, 2017 BILL REGULATING MUNICIPAL USE OF CREDIT CARDS HEARS PROPONENT TESTIMONY The House Government Accountability and Oversight Committee held a second hearing on HB 312, legislation that would regulate the use of credit and debit cards by political subdivisions. Sponsored by Rep. Schuring (R - Canton) and Rep. Greenspan (R - Westlake), the bill received proponent testimony from State Auditor David Yost who shared with the committee that the legislation was proposed to address the use of credit cards by local governments which has become more prevalent in recent years. Auditor Yost commented, "Unfortunately, the incidence of credit card fraud by local government officials has become more prevalent as the use has increased. -

2015 Deloitte Development LLC

How are digital trends reshaping government financial organizations? Findings from Deloitte NASACT 2015 Digital Government Transformation Survey A publication of Deloitte and the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers (NASACT) Message from NASACT Findings from the Deloitte NASACT 2015 Digital Government Transformation Survey of US state and local financial government executives help shed light on the state of digital transformation in government. A total of 33 NASACT members, with diverse functional and organizational backgrounds, participated in the survey. This is a subset of Deloitte’s Global Digital Government Transformation Survey that covered 1,205 public sector executives across 70+ countries during January and February 2015. The survey explores how digital transformation is reshaping state and local governments. It seeks to understand what strategies government organizations are using to navigate the digital roadmap and to identify the areas of greatest opportunity in adapting a digital-first strategy. The organizations have to recognize that digital transformation is not just about implementing digital technologies. They have to create a strategic plan to best implement a digital transformation by taking into consideration a number of issues, such as: • How does the culture of an organization impact digital transformation? • Do leaders and workforces have sufficient skills and resources to successfully achieve digital transformation? • What procurement processes are in place to provide much-needed flexibility to design and develop digital services? Not surprisingly, many organizations recognize hurdles to manage the digital transition in all of these areas. At least two-thirds of the organizations find it challenging to manage digital transition in each — culture, leadership, workforce, and procurement. -

Horizon Health Services, Llc Cuyahoga County

HORIZON HEALTH SERVICES, LLC CUYAHOGA COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page Independent Auditor’s Report .................................................................................................................... 1 Compliance Examination Report ............................................................................................................... 3 Recommendation: Provider Qualifications ................................................................................................. 9 Recommendation: Service Documentation ............................................................................................... 10 Recommendation: Authorization to Provide Services .............................................................................. 12 Official Response ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Auditor of State Conclusion........................................................................................................................ 13 Appendix I: Summary of Sample Record Analysis – Nursing Services ..................................................... 14 Appendix II: Summary of Sample Record Analysis – Home Health Aide Services ................................... 15 Appendix III: Summary of Sample Record Analysis – Personal Care Aide Services ................................ 16 Appendix IV: Provider’s Response ........................................................................................................... -

The State Role in Local Government Financial Distress

A report from July 2013 The State Role in Local Government Financial Distress As cities confront financial challenges, states weigh whether to help them pull through The Pew Charitable Trusts Susan K. Urahn, executive vice president Michael Ettlinger, senior director Meghan Salas Atwell Stephen Fehr Kil Huh Aidan Russell External reviewers This report benefited tremendously from the insights and expertise of two external reviewers: Matt Fabian, managing director, Municipal Market Advisors, and James E. Spiotto, partner, Chapman and Cutler, LLP. These experts have found the report’s approach and methodology to be sound. Although they have reviewed the report, neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse its findings or conclusions. Acknowledgments Providing invaluable assistance, Kimberly Furdell helped with the data collection, verification, and analysis; Sarah McLaughlin Emmans aided in concept development; and Rob Gurwitt contributed to reporting. We would like to thank the following colleagues for their insights and guidance: Sarah Babbage, Ike Emejuru, Alicia Mazzara, Sergio Ritacco, Matthew Separa, and Robert Zahradnik. We also thank Dan Benderly, Jennifer V. Doctors, Bailey Farnsworth, Sarah Leiseca, Jeremy Ratner, Kodi Seaton, Kate Starr, and Gaye Williams for providing valuable feedback and production assistance on this report. Finally, we thank the many state officials and other experts in the field who were so generous with their time, knowledge, and expertise. Note: In April 2016, this report was updated to include revised information about Louisiana’s intervention practices and to improve the clarity of citations. The Pew Charitable Trusts is driven by the power of knowledge to solve today’s most challenging problems. Pew applies a rigorous, analytical approach to improve public policy, inform the public, and invigorate civic life. -

Assessing Existing Local Government Fiscal Early Warning System Through Four State Case Studies: Colorado, Louisiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania

Assessing Existing Local Government Fiscal Early Warning System through Four State Case Studies: Colorado, Louisiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania Michigan State University Extension Michigan Center for Local Government Finance & Policy By Eric Scorsone and Natalie Pruett Back to Contents 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 II. Overview of Fiscal Solvency Measures���������������������������������������������������������������4 III. Case Study Presentation: Four Existing Local Fiscal Warning Systems��������������������������������������������������5 Pennsylvania Early Warning System for Municipal Recovery ���������������������������������� 5 Ohio Fiscal Health Indicators �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 Louisiana Early Warning System for Fiscal Administration ������������������������������������ 15 Colorado Fiscal Stability Initiative ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 23 IV. Ratio Analysis, Observations, and Recommendations ���������������������������27 Selecting Ratios ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 28 Setting Benchmarks �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 35 Scoring �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Village Caucus Notes Tuesday, January 19, 2021

2021 TMACOG Virtual General Assembly Village Caucus Notes Tuesday, January 19, 2021 Call to Order/Welcome – The Village Caucus met on Tuesday, January 19, 2021 via GoToMeeting video teleconference. Rosanna Hoelzle, administrator for the Village of Swanton and the moderator of the caucus, called the meeting to order and welcomed everyone. Instructions were given to enter name and affiliations into the chat box to help with attendance. Ms. Hoelzle explained the purpose of the caucus for anyone who may be new to TMACOG. Caucus members in attendance included: • Anne Auger – Administrator, Village of Put in Bay • Quinton Babcock – Mayor, Village of Oak Harbor • Carol Bailey – Mayor, Village of Pemberville • Genna Biddix – Administrator, Village of Fayette • Dave Borer, Mayor – Village of Fayette • Michael Brillhart – Administrator, Village of North Baltimore • Dana Dunbar – Council Member, Village of Ottawa Hills • Randy Genzman – Administrator, Village of Oak Harbor • Adam Greenslade – Mayor, Village of Green Springs • Rosanna Hoelzle – Administrator, Village of Swanton • David Hower – Administrator, Village of Elmore • Michelle Ish – Village Council, Village of Oak Harbor • Nancy Perry – Council Member, Village of Haskins • Richard Sauerlender – Mayor, Village of Metamora • John Wenzlick – Administrator, Village of Ottawa Hills Other TMACOG members and guests in attendance included: • Meg Adams, External Affairs, FirstEnergy/Toledo Edison • Sheri Bokros, Vice President, The Mannik & Smith Group, Inc. • Lori Brodie – Northwest Ohio Regional Liaison, Office of Ohio State Auditor Keith Faber • Meghan Gallagher, Regional Business Development Coordinator and Account Manager, Ohio Turnpike & Infrastructure Commission • Theresa Gavarone – State Senator, 2nd District Ohio • Sarah Helbig – Executive Director of Marketing, Jones & Henry Engineers • Erica Krause – Northwest Ohio Regional Representative, Office of U.S. -

Charter School Vulnerabilities to Waste, Fraud and Mismanagement

The Center for Popular Democracy is a nonprofit organization that promotes equity, opportunity, and a dynamic democracy in partnership with innovative base-building organizations, organizing networks and alliances, and progressive unions across the country. Integrity in Education is a nonprofit organization dedicated to restoring integrity in education. Integrity in Education exists to shine a light on the people making a positive difference for children, and to expose and oppose the corporate interest groups standing in their way. This is report is available at www.integrityineducation.org and www.populardemocracy.org. he title of this report, Charter School Vulnerabilities To Waste, Fraud, And Abuse, was borrowed from the title of a section of a report that appeared in The Department of T Education’s Office of the Inspector General’s Semiannual Report to Congress, No. 60.1 The report references a memorandum issued by the OIG to the Department. The OIG stated that the purpose of the memorandum was to, “alert you of our concern about vulnerabilities in the oversight of charter schools.” 2 The report went on to state that the OIG had experienced, “a steady increase in the number of charter school complaints” and that state level agencies were failing “to provide adequate oversight needed to ensure that Federal funds [were] properly used and accounted for.”3 The purpose of this report is to echo the warning issued by the OIG and to inform the public and lawmakers of the mounting risk that an inadequately regulated charter industry presents to our communities and taxpayers. Our examination, which focused on 15 large charter markets*, found fraud, waste, and abuse cases totaling over $100 million in losses to taxpayers.† Despite rapid growth in the charter school industry, no agency, federal or state, has been given the resources to properly oversee it. -

County Caucus Notes Wednesday, January 20, 2021

2021 TMACOG Virtual General Assembly County Caucus Notes Wednesday, January 20, 2021 Call to Order/Welcome – The County Caucus met on Wednesday, January 20, 2021 at 8:30 a.m. via GoToMeeting video/teleconference. Ottawa County Commissioner and TMACOG Chair Mark Stahl, the moderator of the caucus, called the meeting to order and welcomed everyone. Commissioner Stahl explained the purpose of the caucus for those new to TMACOG. Caucus members in attendance included: • Carlos Baez – County Engineer, Sandusky County Engineer’s Office • Mark Coppeler – Commissioner, Ottawa County Board of Commissioners • Don Douglas – Commissioner, Ottawa County Board of Commissioners • Theresa Garcia – County Administrator, Sandusky County Board of Commissioners • Doris Herringshaw – Commissioner, Wood County Board of Commissioners • Andrew Kalmar – County Administrator, Wood County Board of Commissioners • Craig LaHote – Commissioner, Wood County Board of Commissioners • Ron Lajti – County Engineer, Ottawa County Engineer’s Office • Scott Miller – Commissioner, Sandusky County Board of Commissioners • Mike Pniewski – County Engineer, Lucas County Engineer’s Office • Mark Stahl – Commissioner, Ottawa County Board of Commissioners & Chair, TMACOG • Carri Stanley – Assistant County Administrator, Wood County Board of Commissioners • Russ Zimmerman – Commissioner, Sandusky County Board of Commissioners Other TMACOG members and guests in attendance included: • Meg Adams – External Affairs, FirstEnergy/Toledo Edison • Mike Avellano – Engineer Program Director, -

TABLE 4.30 State Comptrollers, 2018

AUDITORS AND COMPTROLLERS TABLE 4.30 State Comptrollers, 2018 Elected Civil service Legal Method Approval or Length comptrollers or merit basis for of confirmation, of maximum system State Agency or office Name Title office selection if necessary term consecutive terms employee Alabama Office of the State Comptroller Kathleen Baxter State Comptroller S (c) AG (b) … « Alaska Division of Finance Kelly O’Sullivan Division Director S (d) AG (a) … « Arizona General Accounting Office D. Clark Partridge State Comptroller S (d) AG (b) … … Dept. of Finance and Larry Walther Chief Fiscal Officer, S G … (a) … … Arkansas Administration Director Office of the State Auditor Andrea Lea State Auditor Office of the State Controller Betty Yee (D) State Controller C E … 4 yrs. 2 terms … California Department of Finance Todd Jerue Chief Operating Officer Department of Personnel and Colorado Bob Jaros State Controller S (d) AG (o) … « Administration Connecticut Office of the Comptroller Kevin P. Lembo (D) Comptroller C E … 4 yrs. unlimited … Director, Division of Delaware Dept. of Finance Jane Cole S G AL (a) … … Accounting Florida Dept. of Financial Services Jimmy Patronis Chief Financial Officer C,S E … 4 yrs. 2 terms … State Accounting Georgia State Accounting Office Alan Skelton S G … (a) … … Officer Dept. of Accounting and Hawaii Roderick Becker State Comptroller S G AS 4 yrs. … … General Services Idaho Office of State Controller Brandon Woolf State Controller C E … 4 yrs. 2 terms … Illinois Office of the State Comptroller Susana Mendoza (D) State Comptroller C E … 4 yrs. unlimited … Indiana Office of the Auditor of State Tera Klutz Auditor of State C E … 4 yrs.