Amicus Curiae Brief of Nu Dotco, Llc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privacy Policy V1.1

CENTRALNIC LTD REGISTRY PRIVACY POLICY Version 1.1 September 2018 CentralNic Ltd 35-39 Moorgate London EC2R 6AR Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... 2 AMENDMENT ISSUE SHEET ................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 DATA PROTECTION RIGHTS ................................................................................................................. 5 RELATIONSHIP WITH REGISTRARS ......................................................................................................... 6 WHAT INFORMATION CENTRALNIC COLLECTS .......................................................................................... 6 INFORMATION CENTRALNIC DOES NOT COLLECT ....................................................................................... 8 HOW INFORMATION IS STORED ............................................................................................................ 8 HOW WE USE INFORMATION ............................................................................................................... 8 HOW INFORMATION IS PROTECTED ..................................................................................................... 13 HOW INFORMATION IS DELETED ........................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2020

CentralNic Group Plc | Annual report 2020 Annual report Building a better digital economy CentralNic Group Plc Annual report 2020 Purpose To make the internet everybody’s domain. Vision To make the extraordinary potential of the internet available to all. Mission To provide tools to as many people as possible to realise their aspirations online. Contents Strategic report Governance Our highlights 01 Board of Directors 26 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 48 What we do 02 Corporate governance 28 Company statement Delivering value and growth 04 Audit Committee report 31 of financial position 83 Chairman’s statement 06 Remuneration Committee report 32 Company statement of changes in equity 84 Market opportunity 07 Directors’ report 35 Notes to the Company Our business model and strategy 08 Financial statements financial statements 85 Chief Executive Officer’s report 10 Independent auditor’s report 39 Particulars of subsidiaries Environmental, social and associates 91 and governance 14 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 44 Chief Financial Officer’s report 18 Additional information Consolidated statement Shareholder information 94 Risks 22 of financial position 45 Glossary 96 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 46 Consolidated statement of cash flows 47 Find out more at: www.centralnicgroup.com Strategic report Governance Financial statements Additional information Our highlights Record organic growth in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Financial highlights Revenue growth Net revenue/gross profit Adjusted EBITDA growth Operating profit growth (USD m) growth (USD m) (USD m) (USD m) 241.2 76.3 30.6 0.4 (2.8) 42.8 17.9 109.2 +121% +78% +71% n.m. -

Afilias Limited Request 28 January 2020

Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) Request January 17, 2020 Registry Operator Afilias Limited Request Details Case Number: 00941695 This Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) request form should be submitted for review by ICANN org when a registry operator is adding, modifying, or removing a Registry Service for a TLD or group of TLDs. The RSEP Process webpage provides additional information about the process and lists RSEP requests that have been reviewed and/or approved by ICANN org. If you are proposing a service that was previously approved, we encourage you to respond similarly to the most recently approved request(s) to facilitate ICANN org’s review. Certain known Registry Services are identified in the Naming Services portal (NSp) case type list under “RSEP Fast Track” (example: “RSEP Fast Track – BTAPPA”). If you would like to submit a request for one of these services, please exit this case and select the specific Fast Track case type. Unless the service is identified under RSEP Fast Track, all other RSEP requests should be submitted through this form. Helpful Tips • Click the “Save” button to save your work. This will allow you to return to the request at a later time and will not submit the request. • You may print or save your request as a PDF by clicking the printer icon in the upper right corner. You must click “Save” at least once in order to print the request. • Click the “Submit” button to submit your completed request to ICANN org. • Complete the information requested below. All fields marked with an asterisk (*) are required. -

Telecommunications/Software & IT Services

Telecommunications/Software & IT Services UK Mid -Cap Networking/communications: three stocks to watch 22 June 2021 Bharath Nagaraj Analyst +44 20 3753 3044 [email protected] Benjamin May Analyst +44 20 3465 2667 [email protected] Edward James, CFA Analyst +44 20 3207 7811 [email protected] Sean Thapar Analyst +44 20 3465 2657 [email protected] ATLAS ALPHA • THOUGHT LEADERSHIP • ACCESS • SERVICE UK Mid Cap Telecommunications/Software & IT Services THE TEAM Bharath Nagaraj joined the UK Mid-Cap team at Berenberg in September 2020. He has seven years of sell-side and buy-side experience, after starting off his career at Hewlett- Packard as a system software engineer. Bharath has a master’s in finance with a distinction from London Business School and a master’s in financial engineering from the National University of Singapore. He has also completed CFA level II. Benjamin May joined Berenberg in 2012 and has helped build the UK mid-cap equity research team. He currently leads the mid-cap TMT product, which was ranked top five in Extel's investment survey in 2017 and 2018. Ben has previous experience at Berenberg, working in the telecommunications and economics research teams. Prior to this, Ben gained some strategy consultancy experience. Ben was a Santander Scholar at UCL, where he gained a distinction in his MSc management degree. He also holds a BSc from Warwick University. Edward James joined the UK Mid-Cap team at Berenberg in July 2016 from Aviva Investors, where he worked for two years in investment risk. Edward gained a Bcom (Hons) with Distinction in Financial Analysis & Portfolio Management, and a BSc in Property Investment majoring in Economics from the University of Cape Town. -

Registry Operator's Report

REGISTRY OPERATOR’S REPORT July 2007 Afilias Limited Monthly Operator Report – July 2007 As required by the ICANN/Afilias Limited Registry Agreement (Section 3.1(c)(iv)) this report provides an overview of Afilias Limited activity through the end of the reporting month. The information is primarily presented in table and chart format with text explanations as deemed necessary. Information is provided in order as listed in Appendix 4 of the Registry Agreement. Report Index Section 1 Accredited Registrar Status Section 2 Service Level Agreement Performance Section 3 INFO Zone File Access Activity Section 4 Completed SRS/System Software Releases Section 5 WhoIs Service Activity Section 6 Total Number of Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 7 Daily Transaction Range Copyright © 2001-2007 Afilias Limited Page 2 of 9 Afilias Limited Monthly Operator Report – July 2007 Section 1 – Accredited Registrar Status – July 2007 The following table displays the current number and status of the ICANN accredited registrars. The registrars are grouped into three categories: 1.Operational registrars: Those who have authorized access into the Shared Registration System (SRS) for processing domain name registrations. 2.Registrars in the Ramp-up Period: Those who have received a password to the Afilias Operational Test and Evaluation (OT&E) environment. The OT&E environment is provided to allow registrars to develop and test their systems with the SRS. 3.Registrars in the Pre-Ramp-up Period: Those who have been sent a welcome letter from Afilias, but have not yet executed the Registry Confidentiality Agreement and/or have not yet submitted a completed Registrar Information Sheet. -

SAC101 SSAC Advisory Regarding Access to Domain Name Registration Data

SAC101 SSAC Advisory Regarding Access to Domain Name Registration Data An Advisory from the ICANN Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC) 14 June 2018 SSAC Advisory Regarding Access to Domain Name Registration Data Preface This is an advisory to the ICANN Board, the ICANN Organization staff, the ICANN community, and, more broadly, the Internet community from the ICANN Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC) about access to domain name registration data and Registration Data Directory Services (RDDS). The SSAC focuses on matters relating to the security and integrity of the Internet’s naming and address allocation systems. This includes operational matters (e.g., pertaining to the correct and reliable operation of the root zone publication system), administrative matters (e.g., pertaining to address allocation and Internet number assignment), and registration matters (e.g., pertaining to registry and registrar services). SSAC engages in ongoing threat assessment and risk analysis of the Internet naming and address allocation services to assess where the principal threats to stability and security lie, and advises the ICANN community accordingly. The SSAC has no authority to regulate, enforce, or adjudicate. Those functions belong to other parties, and the advice offered here should be evaluated on its merits. SAC101 1 SSAC Advisory Regarding Access to Domain Name Registration Data Table of Contents Preface 1 Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 3 2 Background 6 3 Uses of Domain Registration Data for Security and Stability -

("Agreement"), Is Between Tucows Domains Inc

MASTER DOMAIN REGISTRATION AGREEMENT THIS REGISTRATION AGREEMENT ("Agreement"), is between Tucows Domains Inc. ("Tucows") and you, on behalf of yourself or the entity you represent ("Registrant"), as offered through the Reseller participating in Tucows' distribution channel for domain name registrations. Any reference to "Registry" or "Registry Operator" shall refer to the registry administrator of the applicable top-level domain ("TLD"). This Agreement explains Tucows' obligations to Registrant, and Registrant's obligations to Tucows, for the domain registration services. By agreeing to the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement, Registrant agrees to be bound by the rules and regulations set forth in this Agreement, and by a registry for that particular TLD. DOMAIN NAME REGISTRATION. Domain name registrations are for a limited term, which ends on the expiration date communicated to the Registrant. A domain name submitted through Tucows will be deemed active when the relevant registry accepts the Registrant's application and activates Registrant's domain name registration or renewal. Tucows cannot guarantee that Registrant will obtain a desired domain name, even if an inquiry indicates that a domain name is available at the time of application. Tucows is not responsible for any inaccuracies or errors in the domain name registration or renewal process. FEES. Registrant agrees to pay Reseller the applicable service fees prior to the registration or renewal of a domain. All fees payable here under are non-refundable even if Registrant's domain name registration is suspended, cancelled or transferred prior to the end of your current registration term. TERM. This Agreement will remain in effect during the term of the domain name registration as selected, recorded and paid for at the time of registration or renewal. -

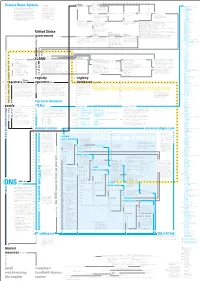

Domain Name System Concept

8 originally chartered standards charters 0 Concept Map organizations include ISoc members form 243 active ccTLDs Domain Name System rely on .ac Ascension Island (licensed) 28 Internet Society (ISoc) is a professional .ad Andorra A concept map is a web of terms. Verbs membership society with more than 150 This diagram is a model of the Domain .ae United Arab Emirates connect nouns to form propositions. organizations and 11,000 individual mem- .af Afghanistan 27 Name System (DNS), a system vital to the Groups of propositions form larger struc- bers from over 182 countries. tures. Examples and details accompany .ag Antigua and Barbuda smooth operation of the Internet. The goal most terms. More important terms re- .ai Anguilla of the diagram is to explain what DNS ceive visual emphasis; less important 11 .al Albania terms, details, and examples are in gray. IETF sponsors working groups are managed by IESG decisions can be appealed to IAB provides advice to IANA functions were moved to .am Armenia is, how it works, and how it’s governed. Terms related to names and addresses write approves .an Netherlands Antilles The diagram knits together many facts (the heart of DNS) are in blue. Terms Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Internet Engineering Steering Internet Architecture Board (IAB) Internet Assigned Numbers .ao Angola followed by a number link to terms pre- is a voluntary, non-commercial organization Group (IESG) Authority (IANA) originally handled .aq Antarctica about DNS in hopes of presenting a com- ceded by the same number. comprised of individuals concerned with the many of the functions that are now 626,000 .ar Argentina prehensive picture of the system and the evolution of the architecture and operation ICANN’s responsibility. -

Registry Privacy Statement

Registry Privacy Statement INTRODUCTION About Afilias provides reliable, secure management of Internet top-level domains. As the registry operator for top-level domains (TLDs), Afilias maintains the responsibility for the operation of each TLD, including maintaining a registry of the domain names within each TLD. In connection with generic top-level domains (gTLDs), Afilias serves as the registry operator for these gTLDs under contracts with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a not-for-profit private sector organization that is charged with coordinating and ensuring the stable and secure operation of the Internet’s unique identifier systems (https://www.icann.org). In connection with country-code top-level domains (ccTLDs), Afilias has entered into separate legal arrangement with the ccTLD managers for the provision of these services. Afilias is made up of Afilias Limited and its subsidiaries: Afilias Technologies Limited, Monolith Registry, LLC, and other registry operators (the “Afilias Group”). This privacy notice is issued on behalf of the Afilias Group so when we mention “Afilias”, “we”, “us” or “our”, we are referring to the relevant company in the Afilias Group responsible for your data. General Afilias is committed to processing your personal data in a fair and lawful manner. This Privacy Statement aims to provide information about Afilias’ collection and processing of personal data. Scope This Privacy Statement relates to our domain name registry system only. It is intended to outline the information we collect, how it is stored, used, shared, and protected, and your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your information. It is important that you read this Privacy Statement together with any other privacy policy or fair processing notice we may provide on specific occasions when we are collecting or processing personal data. -

Which Internet Registries Offer the Best Protection for Domain Owners?

Which Internet registries offer the best protection for domain owners? Jeremy Malcolm, Senior Global Policy Analyst, EFF Gus Rossi, Global Policy Director, Public Knowledge Mitch Stoltz, Senior Staff Attorney, EFF July 27, 2017 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE 1 In the Internet’s early days, those wishing to register their own domain name had only a few choices of top-level domain to choose from, such as .com, .net, or .org. Today, users, innovators, and companies can get creative and choose from more than a thousand top-level domains, such as .cool, .deals, and .fun. But should they? It turns out that not every top-level domain is created equal when it comes to protecting the domain holder’s rights. Depending on where you register your domain, a rival, troll, or officious regulator who doesn’t like what you’re doing with it could wrongly take it away, or could unmask your identity as its owner—even if they are from overseas. To help make it easier to sort the .best top-level domains from the .rest, EFF and Public Knowledge have gotten together to provide this guide to inform you about your choices. There’s no one best choice, since not every domain faces the same challenges. But with the right information in hand, you’ll be able to make the choice that makes sense for you. Before proceeding it’s worth noting the difference between a registry and a registrar. The domain registry is like a wholesaler, who operates an entire top-level domain (TLD) such as .com. -

Sued Enom and Tucows

Case 2:17-cv-01310-RSM Document 1 Filed 08/30/17 Page 1 of 27 1 HON.___________________ 2 3 4 5 6 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 8 AT SEATTLE 9 NAMECHEAP, INC., a Delaware Case No. 2:17-cv-1310 corporation, 10 COMPLAINT FOR: Plaintiff, 11 v. 1. BREACH OF CONTRACT 12 2. BREACH OF CONTRACT—SPECIFIC TUCOWS, INC., a Pennsylvania PERFORMANCE 13 corporation; ENOM, INC., a Nevada 3. BREACH OF IMPLIED DUTY OF corporation; and DOES 1 through 10, GOOD FAITH AND FAIR DEALING 14 Defendants. 4. UNJUST ENRICHMENT 15 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 16 17 Plaintiff Namecheap, Inc. (“Plaintiff” or “Namecheap”), by and through its undersigned 18 attorneys, hereby complains against Defendant Tucows, Inc. (“Tucows”), Defendant eNom, Inc. 19 (“eNom” and collectively with Tucows, “Defendants”), and defendants identified as Does 1 20 through 10 (“Doe Defendants”) as follows: 21 NATURE OF THE ACTION 22 1. Namecheap brings this action against eNom and its successor-in-interest, Tucows, 23 to enforce a contractual obligation to transfer all Namecheap-managed domains on the eNom 24 platform to Namecheap. A true and correct copy of the July 31, 2015 Master Agreement 25 executed by Namecheap, on the one hand, and eNom and United TLD Holding Co., Ltd. trading 26 as Rightside Registry (“Rightside”), on the other hand (the “Master Agreement”) is attached as 27 Exhibit A, with redactions to preserve confidentiality of information not relevant to this dispute. focal PLLC COMPLAINT 900 1st Avenue S., Suite 201 CASE NO. _______________ - 1 Seattle, WA 98134 Tel (206) 529-4827 Fax (206) 260-3966 Case 2:17-cv-01310-RSM Document 1 Filed 08/30/17 Page 2 of 27 1 2. -

2020-12-09 RIPE WG 2020-12-01-Data

Measuring ROA deployment at the top of the DNS Or, Taking a Simple Number and Really, Really, Really, Over Thinking It Edward Lewis RIPE WG Interim Session 9 December 2020 | 1 Origin of This Work • CENTR Jamboree 2019 – Job Snijders on the agenda to talk to Registry Operators – The Topic: RPKI for ccTLD Peers • Why the ccTLDs ought to validate routing information – Expected a talk on how RPKI could protect routes to name servers • So, I began to work on a talk related to that (route information signing) | 2 Setting Expectations • The central theme of this talk is the methodology – What is covered in the assessment – How the experiment space is divided • There's not much detail on RPKI and ROA's progress – Not enough time has elapsed to see penetration – No consideration of whether obstacles exist | 3 Measuring ROA Deployment in the DNS Core ¤ This talk is not promoting "ROA adoption", just measuring it ¡ An application/service-specific look at adoption • The DNS service, particularly the authoritative core ¤ What is the DNS Core? ¤ What are ROAs? | 4 The DNS Core (in Cartoon Form) root ccTLDs gTLDs arpa. in-addr ip6 The sub-ccTLDs sub-gTLDs # # Core # # | 5 I May "Slip Up" and talk about TLDs this way in the talk root ccTLDs gTLDs arpa. in-addr ip6 The sub-ccTLDs sub-gTLDs # # Core # # | 6 ROAs = Route Origination Authorization • RPKI is a Public Key Infrastructure framework deployed to secure BGP against invalid or unauthorized route announcements – ROA stands for Route Origination Authorization is a cryptographic attestation that the ASN is authorized to originate a network prefix IP Prefix Next ASN Another ASN Another ASN ..