Amicus Curiae Brief of Verisign, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afilias Limited Request 28 January 2020

Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) Request January 17, 2020 Registry Operator Afilias Limited Request Details Case Number: 00941695 This Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) request form should be submitted for review by ICANN org when a registry operator is adding, modifying, or removing a Registry Service for a TLD or group of TLDs. The RSEP Process webpage provides additional information about the process and lists RSEP requests that have been reviewed and/or approved by ICANN org. If you are proposing a service that was previously approved, we encourage you to respond similarly to the most recently approved request(s) to facilitate ICANN org’s review. Certain known Registry Services are identified in the Naming Services portal (NSp) case type list under “RSEP Fast Track” (example: “RSEP Fast Track – BTAPPA”). If you would like to submit a request for one of these services, please exit this case and select the specific Fast Track case type. Unless the service is identified under RSEP Fast Track, all other RSEP requests should be submitted through this form. Helpful Tips • Click the “Save” button to save your work. This will allow you to return to the request at a later time and will not submit the request. • You may print or save your request as a PDF by clicking the printer icon in the upper right corner. You must click “Save” at least once in order to print the request. • Click the “Submit” button to submit your completed request to ICANN org. • Complete the information requested below. All fields marked with an asterisk (*) are required. -

Registry Operator's Report

REGISTRY OPERATOR’S REPORT July 2007 Afilias Limited Monthly Operator Report – July 2007 As required by the ICANN/Afilias Limited Registry Agreement (Section 3.1(c)(iv)) this report provides an overview of Afilias Limited activity through the end of the reporting month. The information is primarily presented in table and chart format with text explanations as deemed necessary. Information is provided in order as listed in Appendix 4 of the Registry Agreement. Report Index Section 1 Accredited Registrar Status Section 2 Service Level Agreement Performance Section 3 INFO Zone File Access Activity Section 4 Completed SRS/System Software Releases Section 5 WhoIs Service Activity Section 6 Total Number of Transactions by Subcategory by Month Section 7 Daily Transaction Range Copyright © 2001-2007 Afilias Limited Page 2 of 9 Afilias Limited Monthly Operator Report – July 2007 Section 1 – Accredited Registrar Status – July 2007 The following table displays the current number and status of the ICANN accredited registrars. The registrars are grouped into three categories: 1.Operational registrars: Those who have authorized access into the Shared Registration System (SRS) for processing domain name registrations. 2.Registrars in the Ramp-up Period: Those who have received a password to the Afilias Operational Test and Evaluation (OT&E) environment. The OT&E environment is provided to allow registrars to develop and test their systems with the SRS. 3.Registrars in the Pre-Ramp-up Period: Those who have been sent a welcome letter from Afilias, but have not yet executed the Registry Confidentiality Agreement and/or have not yet submitted a completed Registrar Information Sheet. -

("Agreement"), Is Between Tucows Domains Inc

MASTER DOMAIN REGISTRATION AGREEMENT THIS REGISTRATION AGREEMENT ("Agreement"), is between Tucows Domains Inc. ("Tucows") and you, on behalf of yourself or the entity you represent ("Registrant"), as offered through the Reseller participating in Tucows' distribution channel for domain name registrations. Any reference to "Registry" or "Registry Operator" shall refer to the registry administrator of the applicable top-level domain ("TLD"). This Agreement explains Tucows' obligations to Registrant, and Registrant's obligations to Tucows, for the domain registration services. By agreeing to the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement, Registrant agrees to be bound by the rules and regulations set forth in this Agreement, and by a registry for that particular TLD. DOMAIN NAME REGISTRATION. Domain name registrations are for a limited term, which ends on the expiration date communicated to the Registrant. A domain name submitted through Tucows will be deemed active when the relevant registry accepts the Registrant's application and activates Registrant's domain name registration or renewal. Tucows cannot guarantee that Registrant will obtain a desired domain name, even if an inquiry indicates that a domain name is available at the time of application. Tucows is not responsible for any inaccuracies or errors in the domain name registration or renewal process. FEES. Registrant agrees to pay Reseller the applicable service fees prior to the registration or renewal of a domain. All fees payable here under are non-refundable even if Registrant's domain name registration is suspended, cancelled or transferred prior to the end of your current registration term. TERM. This Agreement will remain in effect during the term of the domain name registration as selected, recorded and paid for at the time of registration or renewal. -

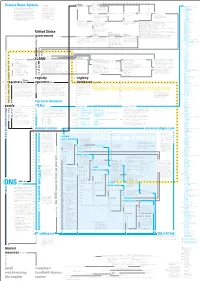

Domain Name System Concept

8 originally chartered standards charters 0 Concept Map organizations include ISoc members form 243 active ccTLDs Domain Name System rely on .ac Ascension Island (licensed) 28 Internet Society (ISoc) is a professional .ad Andorra A concept map is a web of terms. Verbs membership society with more than 150 This diagram is a model of the Domain .ae United Arab Emirates connect nouns to form propositions. organizations and 11,000 individual mem- .af Afghanistan 27 Name System (DNS), a system vital to the Groups of propositions form larger struc- bers from over 182 countries. tures. Examples and details accompany .ag Antigua and Barbuda smooth operation of the Internet. The goal most terms. More important terms re- .ai Anguilla of the diagram is to explain what DNS ceive visual emphasis; less important 11 .al Albania terms, details, and examples are in gray. IETF sponsors working groups are managed by IESG decisions can be appealed to IAB provides advice to IANA functions were moved to .am Armenia is, how it works, and how it’s governed. Terms related to names and addresses write approves .an Netherlands Antilles The diagram knits together many facts (the heart of DNS) are in blue. Terms Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Internet Engineering Steering Internet Architecture Board (IAB) Internet Assigned Numbers .ao Angola followed by a number link to terms pre- is a voluntary, non-commercial organization Group (IESG) Authority (IANA) originally handled .aq Antarctica about DNS in hopes of presenting a com- ceded by the same number. comprised of individuals concerned with the many of the functions that are now 626,000 .ar Argentina prehensive picture of the system and the evolution of the architecture and operation ICANN’s responsibility. -

Registry Privacy Statement

Registry Privacy Statement INTRODUCTION About Afilias provides reliable, secure management of Internet top-level domains. As the registry operator for top-level domains (TLDs), Afilias maintains the responsibility for the operation of each TLD, including maintaining a registry of the domain names within each TLD. In connection with generic top-level domains (gTLDs), Afilias serves as the registry operator for these gTLDs under contracts with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a not-for-profit private sector organization that is charged with coordinating and ensuring the stable and secure operation of the Internet’s unique identifier systems (https://www.icann.org). In connection with country-code top-level domains (ccTLDs), Afilias has entered into separate legal arrangement with the ccTLD managers for the provision of these services. Afilias is made up of Afilias Limited and its subsidiaries: Afilias Technologies Limited, Monolith Registry, LLC, and other registry operators (the “Afilias Group”). This privacy notice is issued on behalf of the Afilias Group so when we mention “Afilias”, “we”, “us” or “our”, we are referring to the relevant company in the Afilias Group responsible for your data. General Afilias is committed to processing your personal data in a fair and lawful manner. This Privacy Statement aims to provide information about Afilias’ collection and processing of personal data. Scope This Privacy Statement relates to our domain name registry system only. It is intended to outline the information we collect, how it is stored, used, shared, and protected, and your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your information. It is important that you read this Privacy Statement together with any other privacy policy or fair processing notice we may provide on specific occasions when we are collecting or processing personal data. -

Which Internet Registries Offer the Best Protection for Domain Owners?

Which Internet registries offer the best protection for domain owners? Jeremy Malcolm, Senior Global Policy Analyst, EFF Gus Rossi, Global Policy Director, Public Knowledge Mitch Stoltz, Senior Staff Attorney, EFF July 27, 2017 ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE 1 In the Internet’s early days, those wishing to register their own domain name had only a few choices of top-level domain to choose from, such as .com, .net, or .org. Today, users, innovators, and companies can get creative and choose from more than a thousand top-level domains, such as .cool, .deals, and .fun. But should they? It turns out that not every top-level domain is created equal when it comes to protecting the domain holder’s rights. Depending on where you register your domain, a rival, troll, or officious regulator who doesn’t like what you’re doing with it could wrongly take it away, or could unmask your identity as its owner—even if they are from overseas. To help make it easier to sort the .best top-level domains from the .rest, EFF and Public Knowledge have gotten together to provide this guide to inform you about your choices. There’s no one best choice, since not every domain faces the same challenges. But with the right information in hand, you’ll be able to make the choice that makes sense for you. Before proceeding it’s worth noting the difference between a registry and a registrar. The domain registry is like a wholesaler, who operates an entire top-level domain (TLD) such as .com. -

INTA and Internet Advocacy ICANN 101 Presentation Overview

INTA and Internet Advocacy ICANN 101 Presentation Overview 1. Digital Governance 2. The Domain Name System 3. ICANN 4. Generic Names Supporting Organization (GNSO) A. Non-Contracted Parties House (NCPH) B. Contracted Parties House (CPH) 5. Hot Topics in ICANN A. New gTLDs and Subsequent Rounds B. IANA Transition and Accountability C. Enforcement D. Use of Geographic Terms in Domain Names 2 Introduction to Digital Governance No one person, government, organization, or company governs the digital infrastructure, economy, or society. Digital governance is achieved through the collaborations of multi-stakeholder experts acting through polycentric communities, institutions, and platforms across national, regional, and global spheres. Digital governance may be stratified into three layers: 1. Economic and Societal Layer 2. Logistical Layer 3. Infrastructure Layer 3 Digital Governance https://www.icann.org/news/multimedia/1563 4 Names, Numbers, Protocols Names are the combination of text that we type into a browser. Numbers are the numbers linked to the text. Protocols are the international standards for lookups, queries, and responses. 5 Names, Numbers, Protocols Protocols guide the coordination of names with numbers. This process serves as the road map for an inquiry from point A to point B. • Data is broken into packets and packets reconstructed at their destination. • Addresses are looked up, queries are made as to whether the address is correct, and a response or “no” is sent. • If one “no,” then no resolution. 5 The Root Root Zone/Root Services • 12 organizations from four countries • Administer 13 different root servers • Provide top-level DNS services via hundreds of machines around the world 6 What is IANA? IANA: Internet Assigned Numbers Authority Function: Assigning the operators of top-level domains—such as .uk and .com—and maintaining their technical and administrative details (Protocol Registry) http://www.iana.org/ 7 Registries, Registrars, Registrants Registry: The “wholesaler” of domain names. -

Ben Crawford Interview Transcript in PDF Format

DomainSherpa.com: The Domain Name Authority CentralNic's Path to Growth in the New Gold Rush - With Ben Crawford Watch the full video at: http://www.domainsherpa.com/ben-crawford-centralnic-interview/ When the Gold Rush happened in the mid-1800s in California, it is an often- stated saying that few people got rich, except the people who sold the pickaxes and the shovels. The analogy can be made to the domain name industry. Want to find out who is positioned well for the next Gold Rush, and how you might be able to benefit? Stay tuned. I have three short sponsor messages before we get into today's show. First, if you have a great domain name and nothing to show when people visit, you're missing out on potential advertising revenue, leads, and partnership opportunities. NicheWebsites.com can build you a site quickly with a price option to suit any need -- but as their tagline says, they don't just build websites, they build businesses. Second, if you're buying or selling a domain name or portfolio and you want an estimate of it's value, Estibot.com is the place to go. Just like you'd visit Zillow.com to get an estimate of a house value, Estibot.com provides key information about the most important statistics so you can make an informed decision based on data. Finally, DNX.com is a domain name exchange that uses a reverse auction platform to provide fair market prices for quality domain names that are manually filtered by an experienced broker. -

Jovan Kurbalija Jovan 7Th Edition7th an Introduction to an Introduction INTERNET GOVERNANCE

About the author AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNET GOVERNANCE Dr Jovan Kurbalija is the founding director of DiploFoundation and head of the Geneva Internet The history of this book is long, in Internet time. The Platform. A former original text and the overall approach, including the diplomat, his professional five-basket methodology, were developed in 1997 for and academic background a training course on information and communications is in international law, technology (ICT) policy for government officials from diplomacy, and information Commonwealth countries. In 2004, Diplo published technology. In 1992, he established the Unit for a print version of its Internet governance materials, Internet Governance – Issues, Information Technology and Diplomacy at the AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNET GOVERNANCE An Introduction to in a booklet entitled Actors and Divides. This booklet formed part of the Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies in Jovan Kurbalija Malta. After more than ten years of training, research, Information Society Library, a Diplo initiative driven and publishing, in 2002 the Unit evolved into by Stefano Baldi, Eduardo Gelbstein, and Jovan An Introduction to Internet Governance provides a comprehensive overview of the main is- DiploFoundation. Kurbalija. In 2008, a special, revised version of sues and actors in this field. Written in a clear and accessible way, supplemented with fig- the book, entitled simply An Introduction to Internet ures and illustrations, it focuses on the technical, security, legal, economic, development, Governance, was published in cooperation with Since 1994, Dr Kurbalija has been teaching courses INTERNET sociocultural, and human rights aspects of Internet governance. Providing a brief introduc- NIXI India on the occasion of the 2008 Internet on the impact of ICT/Internet on diplomacy and tion, a summary of major questions and controversies, and a survey of different views and Governance Forum (IGF) held in Hyderabad, India. -

The 2016 African Domain Name System Market Study Final

THE 2016 AFRICAN DOMAIN NAME SYSTEM MARKET STUDY FINAL REPORT 6th June 2017 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many people who made this report possible. They include our many country leaders (who between them spoke Arabic, English, French, Portuguese and a number of other languages), our researchers and our contributors and editors. In particular we would like to mention William Stucke who served as the SACF Project Leader and chief editor, Anriette Esterhuysen, Lucky Masilela, Mark Elkins, Mike Jensen, and Sami Salih. Afilias, EyeDomain, ISOC-SD, ZACR and ZISPA, were particularly helpful in providing data for analysis. Africa Domain Name System Market Study Report, 6th June 2017, SACF Page 2 of 213 AFRICA DOMAIN NAME SYSTEM MARKET STUDY Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 10 1.1 Methodology ...................................................................................................... 10 1.2 The African Ecosystem ........................................................................................ 11 1.3 African DNS Market ............................................................................................. 12 1.4 Success factors................................................................................................... 15 1.5 Recommendations .............................................................................................. 17 1.5.1 Infrastructure .............................................................................................. -

ARI Domain Name Registration

Domain Name Registration System • Domain Name Registration System • Adrian Kinderis – AusRegistry International Domain Name Registration System – Buy vs. Build Domain Name Registration System Domain Name Registration System APTLD Non-Technical Training – Bali Monday February 26th 2007 Adrian Kinderis Managing Director – AusRegistry International • Adrian Kinderis – AusRegistry International Domain Name Registration System – Buy vs. Build WHO IS AUSREGISTRY? AusRegistry • Registry Operator for the .au ccTLD since July 2002 • Operates .au Domain Name Servers (DNS) • Consultation to industry and government • Website: www.ausregistry.com.au AusRegistry International • Consults globally on ccTLD operations • Registry Operator for the Solomon Islands .sb ccTLD • Registry Operator for the Australian ENUM Trial • Registry Operator for the REC Registry • Website: www.ausregistryint.com • Adrian Kinderis – AusRegistry International Domain Name Registration System – Buy vs. Build BUY vs. BUILD “…programming today is a race between software engineers striving to build bigger and better idiot-proof programs, and the Universe is trying to produce bigger and better idiots. So far, the Universe is winning…” Rick Cook • Adrian Kinderis – AusRegistry International Domain Name Registration System – Buy vs. Build BUILD – CONSIDERATIONS • Starting from scratch, why re-invent the wheel? • Time to deploy • Cost • Available resources • Available infrastructure • Experience / expertise • Service levels • End user experience • The unknown • Adrian Kinderis – AusRegistry -

Domain Name Terms and Conditions

Domain name Terms & conditions This Service Schedule is in addition to the Conditions for BT Business Services and forms part of this Contract for Domain Names from BT (the "Service"). 1. SERVICE DESCRIPTION 1.1 The Service provides the domain names services as described at https://business.bt.com/products/computing-apps/domain-registration/ and will be provided to the Customer at the Site. 1.2 In addition to these terms and conditions the Customer will be bound by the terms and conditions of the domain name registry responsible for providing the domain names: a) Generic domain names, including without limitation .com, .net, .org, .biz, .info, .name and .pro. ICANN’s Registrants’ Rights and Responsibilities can be seen at https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/benefits-2013-09-16-en. The Customer acknowledges that it has read, understood and agrees to be bound by all terms and conditions of ICANN's Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the "UDRP"), as amended from time to time, which is hereby incorporated and made a part of this Contract by reference for all gTLD domain name registrations or renewals. b) .eu domain names at http://eurid.eu/en c) .mobi domain names at http://mtld.mobi d) domain names listed at Appendix 1 together with the corresponding registry’s online terms and conditions 1.3 The Customer may order and pay for the Service by telephone or online at https://business.bt.com/products/computing-apps/domain-registration/ or by signing into its BT Business Online Account at https://business.bt.com/ and selecting the Manage Your Services option.