The Key of Ordering: Reading Musical Manuscripts of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians in the Movies: a Century of Saints and Sinners Bryan Polk Penn State Abington, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 17 Article 2 Issue 2 October 2013 10-2-2013 Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners Bryan Polk Penn State Abington, [email protected] Recommended Citation Polk, Bryan (2013) "Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners Abstract This is a book review of Peter Dans' Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009). Author Notes Bryan Polk, Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies at Penn State Abington, is a graduate of Susquehanna University (B.A., Religion, 1977), Lutheran Theological Seminary, Philadelphia (M.Div., 1981), and Beaver College, now Arcadia University, Glenside, PA (M.A., English, 1995). His interests, in addition to religion and film, are in the areas of Fundamentalism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Medieval Literature, and Biblical Studies. His publications include articles on "Jesus as a Trickster God" and "The eM dieval Image of the Hero in the Harry Potter Novels," and he has written six--unpublished--novels. He lives in Abington, Pennsylvania. This book review is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/2 Polk: Christians in the Movies Peter Dans has written an important book, Christians in the Movies: A Century of Saints and Sinners (2009) which brings to light a number of critical insights and presents a lucid exposition of how the Motion Picture Production Code and The Catholic Legion of Decency influenced Hollywood and American society for decades. -

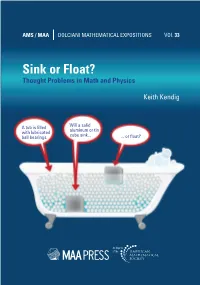

Sink Or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics

AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL AMS / MAA DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS VOL 33 33 Sink or Float? Sink or Float: Thought Problems in Math and Physics is a collection of prob- lems drawn from mathematics and the real world. Its multiple-choice format Sink or Float? forces the reader to become actively involved in deciding upon the answer. Thought Problems in Math and Physics The book’s aim is to show just how much can be learned by using everyday Thought Problems in Math and Physics common sense. The problems are all concrete and understandable by nearly anyone, meaning that not only will students become caught up in some of Keith Kendig the questions, but professional mathematicians, too, will easily get hooked. The more than 250 questions cover a wide swath of classical math and physics. Each problem s solution, with explanation, appears in the answer section at the end of the book. A notable feature is the generous sprinkling of boxes appearing throughout the text. These contain historical asides or A tub is filled Will a solid little-known facts. The problems themselves can easily turn into serious with lubricated aluminum or tin debate-starters, and the book will find a natural home in the classroom. ball bearings. cube sink... ... or float? Keith Kendig AMSMAA / PRESS 4-Color Process 395 page • 3/4” • 50lb stock • finish size: 7” x 10” i i \AAARoot" – 2009/1/21 – 13:22 – page i – #1 i i Sink or Float? Thought Problems in Math and Physics i i i i i i \AAARoot" – 2011/5/26 – 11:22 – page ii – #2 i i c 2008 by The -

Petre Clemens—Lugentium Siccentur Motet in Honor of Clement VI

Petre clemens—Lugentium siccentur motet in honor of Clement VI Ivrea, Biblioteca Capitolare MS 115 Philippe de Vitry (1291–1361) fols. 37v–38 ed. Anna Zayaruznaya 5 + + + + [Triplum] [O. ] & ‚ – ‚‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ – ‚ ‚ ‚ Pe- tre cle - mens tam re quam no - mi‚ - ne cui‚‚ ‚ ‚ – nas-cen - + + [Motetus] [O. ] K K K K ‚ – ‚ & ‚‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ Lu - gen - ti - um sic - cen - tur o - cu‚ - + Tenor [ . ] V b O ‚ ‚ – ‚ ‚ – – – \ [Non\ est inventus] \ 10 + + K & – ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ ‚ ‚ ti Do - nan - tis dex - te - ra non de - fu - + + ‚ ‚ ‚ & – ‚. ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – li, plau - dant se - nes,– ex - ul - tent par - vu - li, V b – – – – \ \ This edition is a companion to Anna Zayaruznaya, “Hockets as Compositional and Scribal Practice in the ars nova Motet—A Letter from Lady Music,” Journal of Musicology 30, no. 4 (2013): 461–501, and the text underlay has been subject to aggressive editorial intervention for reasons discussed there. It is not a diplomatic transcription, but rather an edition employing a simplified form of fourteenth-century French (ars nova) notation in score. Note-values have been left unreduced. Under the reigning mensuration (0. ) there are up to three minims (M) in each semibreve (S), up to three semibreves in each breve (B), and two breves in each long (L). When triple divisions of notes are involved, two processes occur in ars nova notation which do not happen in modern notation. In imperfec- tion, a smaller note “takes” value from a longer one so that the two together can add up to three beats. Thus MS MS denotes an iambic pattern, but if the minims were omitted the semibreves alone would have the value of three minims each (compare triplum and mote- tus in m. -

THE INVENTION of ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY 1. Introductory

THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY Christoph Lüthy Center for Medieval and Renaissance Natural Philosophy University of Nijmegen1 1. Introductory Puzzlement For centuries now, particles of matter have invariably been depicted as globules. These glob- ules, representing very different entities of distant orders of magnitudes, have in turn be used as pictorial building blocks for a host of more complex structures such as atomic nuclei, mole- cules, crystals, gases, material surfaces, electrical currents or the double helixes of DNA. May- be it is because of the unsurpassable simplicity of the spherical form that the ubiquity of this type of representation appears to us so deceitfully self-explanatory. But in truth, the spherical shape of these various units of matter deserves nothing if not raised eyebrows. Fig. 1a: Giordano Bruno: De triplici minimo et mensura, Frankfurt, 1591. 1 Research for this contribution was made possible by a fellowship at the Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschafts- geschichte (Berlin) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant 200-22-295. This article is based on a 1997 lecture. Christoph Lüthy Fig. 1b: Robert Hooke, Micrographia, London, 1665. Fig. 1c: Christian Huygens: Traité de la lumière, Leyden, 1690. Fig. 1d: William Wollaston: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1813. Fig. 1: How many theories can be illustrated by a single image? How is it to be explained that the same type of illustrations should have survived unperturbed the most profound conceptual changes in matter theory? One needn’t agree with the Kuhnian notion that revolutionary breaks dissect the conceptual evolution of science into incommensu- rable segments to feel that there is something puzzling about pictures that are capable of illus- 2 THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY trating diverging “world views” over a four-hundred year period.2 For the matter theories illustrated by the nearly identical images of fig. -

Review Volume 14 (2014) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 14 (2014) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 14 (May 2014), No. 77 Deborah McGrady and Jennifer Bain, eds., A Companion to Guillaume de Machaut. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012. xx + 414 pp. Tables, figures, examples, bibliography, and index. €159.00 (hb); $218.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-9004-22581-7. Review by Jared C. Hartt, Oberlin College Conservatory of Music. The current state of Machaut studies is at an all-time high. With the recent publication of the monograph Guillaume de Machaut: Secretary, Poet, Musician by Elizabeth Eva Leach, the ongoing project “Machaut in the Book” spearheaded by Deborah McGrady and Benjamin Albritton, and the in-progress edition of Machaut’s complete musical and poetic oeuvre led by R. Barton Palmer and Yolanda Plumley, it is fitting—and extremely well-timed—that a companion to this magisterial figure of the Ars Nova be compiled.[1] Editors Deborah McGrady and Jennifer Bain have set an ambitious goal for themselves in this volume of eighteen essays: “As the first collection to propose itself as an introduction to Guillaume de Machaut that would endeavor to provide the non-specialist with a broad overview of his corpus and its treatment in modern research, the present Companion also strives to sketch out new avenues of scholarly inquiry” (p. 7). The contributors, many of whom are Machaut specialists, are thus challenged with providing on the one hand an accessible overview for scholars new to Machaut—and given the book’s title, A Companion, this ought to be its primary objective—while on the other hand providing stimulating dialogue for scholars already fluent in Machaut’s musical and literary language. -

![[Modern Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7488/modern-brown-1037488.webp)

[Modern Brown]

[Modern Brown] by [Olvard Liche Smith ] A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Rutgers University – Newark MFA Program Written under the direction of [Alice Elliott Dark] And approved by Jayne Anne Phillips ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey May 2015 2015 Olvard Liche Smith ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Modern Brown……………………………………………………………………….. 1 Prince………………………………………………………………………………… 32 Strange Blood……………………………………………………………………….... 58 The Last Variant…………………………………………………………………….... 85 Louie’s………………………………………………………………………………… 114 Grand Gesture………………………………………………………………………..... 129 1 Modern Brown I grew up in Hawthorne, California, in a black neighborhood where I never knew if I could say nigga, even around my best friend Marcel. Marcel said nigga all the time but he was shoe polish black and talked with an urban twang. Brown-skinned and mixed, I didn’t even ask permission. We spent all our lunch periods together in the schoolyard, watching the other kids play handball, tetherball, and basketball. I’ve enjoyed playing those games many times, but chilling was just our thing. I was twelve, and didn’t want to play as often anymore; I’d calmed down in some ways and found excitement in others. I was over kid shit, and I assumed Marcel was too. So lunch periods we leaned against the chain- linked fence, discussing basketball or rap—usually rap. “Cam G is mad fresh son,” Marcel said, “That nigga’s flow is amazing. Efren, you gotta hear his new song. Nigga in the video with mad bitches dancing on him, shoving his face in they chest. -

Machaut's Balade Ploures Dames (B32) in the Light of Real Modality

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg CHRISTIAN BERGER Machaut‘s Balade Ploures dames (B32) in the Light of Real Modality Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Machaut’s Music : New Interpretations / Herausgegeben von Elizabeth Eva LEACH. Woodbridge : Boydell Press, 2003 (Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music ; 1), S. 193-204 13 Machaut‘s Balade Ploures dames (B32) in the Light of Real Modality 1 ______________________________________________________________________ Christian Berger Wulf Arlt zum 65. Geburtstag The most reliable basis for our analytical approach to musical works of the late Middle Ages is via their transmisison as written texts. Since these texts are themselves part of an earlier culture, reading them as instructions by which to reproduce the music of this culture requires that we study the presuppositions of this cultural system – the ‚webs of significance’ in which any individual is suspended. As Geertz stresses, to explore this webs does not need ‚an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning.’2 Music history thus relies not only upon musical texts, but also upon the background of elementary music teaching against which to view the assumptions upon which those texts are based. The consequences of such an assumption may be demonstrated by means of a short example of chant repertory.3 Figure 13.1 represents two versions of ‘et porta coeli’, an excerpt from the responsory ‘Terribilis est’, distinguished only by the leap of a fifth at the beginning.4 At about 1100 John of Afflighem criticised this leap as a corruption of chant resulting from ‘the ignorance of the fools’.and the evidence of further testimonies upholds his opinion. -

On the Chiral Archimedean Solids Dedicated to Prof

Beitr¨agezur Algebra und Geometrie Contributions to Algebra and Geometry Volume 43 (2002), No. 1, 121-133. On the Chiral Archimedean Solids Dedicated to Prof. Dr. O. Kr¨otenheerdt Bernulf Weissbach Horst Martini Institut f¨urAlgebra und Geometrie, Otto-von-Guericke-Universit¨atMagdeburg Universit¨atsplatz2, D-39106 Magdeburg Fakult¨atf¨urMathematik, Technische Universit¨atChemnitz D-09107 Chemnitz Abstract. We discuss a unified way to derive the convex semiregular polyhedra from the Platonic solids. Based on this we prove that, among the Archimedean solids, Cubus simus (i.e., the snub cube) and Dodecaedron simum (the snub do- decahedron) can be characterized by the following property: it is impossible to construct an edge from the given diameter of the circumsphere by ruler and com- pass. Keywords: Archimedean solids, enantiomorphism, Platonic solids, regular poly- hedra, ruler-and-compass constructions, semiregular polyhedra, snub cube, snub dodecahedron 1. Introduction Following Pappus of Alexandria, Archimedes was the first person who described those 13 semiregular convex polyhedra which are named after him: the Archimedean solids. Two representatives from this family have various remarkable properties, and therefore the Swiss pedagogicians A. Wyss and P. Adam called them “Sonderlinge” (eccentrics), cf. [25] and [1]. Other usual names are Cubus simus and Dodecaedron simum, due to J. Kepler [17], or snub cube and snub dodecahedron, respectively. Immediately one can see the following property (characterizing these two polyhedra among all Archimedean solids): their symmetry group contains only proper motions. There- fore these two polyhedra are the only Archimedean solids having no plane of symmetry and having no center of symmetry. So each of them occurs in two chiral (or enantiomorphic) forms, both having different orientation. -

Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 © Copyright by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain by Gillian Lucinda Gower Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Elizabeth Randell Upton, Chair This dissertation investigates the relational, representative, and most importantly, constitutive functions of sacred music composed on behalf of and at the behest of British queen- consorts during the later Middle Ages. I argue that the sequences, conductus, and motets discussed herein were composed with the express purpose of constituting and reifying normative gender roles for medieval queen-consorts. Although not every paraliturgical work in the English ii repertory may be classified as such, I argue that those works that feature female exemplars— model women who exemplified the traits, behaviors, and beliefs desired by the medieval Christian hegemony—should be reassessed in light of their historical and cultural moments. These liminal works, neither liturgical nor secular in tone, operate similarly to visual icons in order to create vivid images of exemplary women saints or Biblical figures to which queen- consorts were both implicitly as well as explicitly compared. The Iconography of Queenship is organized into four chapters, each of which examines an occasional musical work and seeks to situate it within its own unique historical moment. In addition, each chapter poses a specific historiographical problem and seeks to answer it through an analysis of the occasional work. -

Article from Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume De Machaut’S Remede De Fortune

Article From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune Mahoney-Steel, Tamsyn Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/37960/ Mahoney-Steel, Tamsyn ORCID: 0000-0003-0037-7281 (2021) From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune. Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, 10 (1). pp. 64-94. ISSN 2162-9544 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dph.2021.0003 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Tamsyn Mahoney-Steel University of Central Lancashire From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune Ostensibly a story about gaining confidence in love, Guillaume de 4Machaut’s Remede de Fortune has been explored as a summa of contemporary musical styles and a treatise on the memorial arts.1 It has also been examined as an important example of the use of citation and allusion in the fourteenth century because it incorporates references to Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun’s Le roman de la Rose. -

CIM/CWRU Joint Music Program Wednesday, Octoberdecember 5, 7,2016 2016

CIM/CWRU Joint Music Program Wednesday, OctoberDecember 5, 7,2016 2016 La Fonteinne amoureuse CarlosCWRU Salzedo Medieval (1885–1961) Ensemble Tango Ross W. Duffin, director Grace Cross & Grace Roepke, harp with CWRU Early Music Singers, ElenaPaul Hindemith Mullins, (1895–1963) director from Sonate für Harfe Sehr langsam Grace Cross ProgramCarlos Salzedo Chanson dans la nuit Grace Cross & Grace Roepke Kyrie from La Messe de Nostre Dame Guillaume de Machaut (ca.1300–77) Caroline Lizotte (b. 1969) from Suite Galactique, op. 39 Early Music Singers Exosphère Gracedirected Roepke by Elena Mullins Pierre Beauchant (1885–1961) Triptic Dance Douce dame Machaut Grace Cross & Grace Roepke Nathan Dougherty, voice withSylvius Medieval Leopold WeissEnsemble (1687–1750) from Lute Sonata no. 48 in F-sharp minor (arr. for guitar by A. Poxon) I. Allemande Lucas Saboya (b. 1980) from Suite Ernestina I. Costurera Quarte estampie royale II. DeAnonymous Algún Modo (Manuscrit du Roy) AllisonBuddy Johnson Monroe, (1915-1977) vielle • Karin Cuellar,Since rebec I Fell for You Laura(arr. for Osterlund, guitar by A. recorderPoxon) • Margaret Carpenter Haigh, harp Andy Poxon, guitar Agustín Barrios (1885–1944) Vals, op. 8, no. 4 Comment qu’a moy lonteinne Machaut J. S. Bach (1685–1750) from Sonata no. 3 in C major, BWV 1005 Margaret Carpenter Haigh, voice IV. Allegro assai Heitorwith ensemble Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) Etude no. 7 Year Yoon, guitar Portrait of Helen Sears, 1895. John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Oil on canvas; 167.3 x 91.4 cm. Museum of Fine(continued Arts, Boston Gift of Mrs. onJ. D. Cameron reverse) Bradley 55.1116. -

Levitsky Dissertation

The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Anne Levitsky All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky This dissertation explores the relationship of the act of singing to being a human in the lyric poetry of the troubadours, traveling poet-musicians who frequented the courts of contemporary southern France in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. In my dissertation, I demonstrate that the troubadours surpass traditionally-held perceptions of their corpus as one entirely engaged with themes of courtly romance and society, and argue that their lyric poetry instead both displays the influence of philosophical conceptions of sound, and critiques notions of personhood and sexuality privileged by grammarians, philosophers, and theologians. I examine a poetic device within troubadour songs that I term ‘personified song’—an occurrence in the lyric tradition where a performer turns toward the song he/she is about to finish singing and directly addresses it. This act lends the song the human capabilities of speech, motion, and agency. It is through the lens of the ‘personified song’ that I analyze this understudied facet of troubadour song. Chapter One argues that the location of personification in the poetic text interacts with the song’s melodic structure to affect the type of personification the song undergoes, while exploring the ways in which singing facilitates the creation of a body for the song.