This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Databases and Ebook Collections 2012-2013

SCHOLARSHIP PUBLISHER Databases and ebook collections 2012-2013 www.classiques-garnier.com Classiques Garnier Digital offers academic libraries, public and research centres access to databases in the fields of literature, the humanities and the social sciences.Teachers, academics, researchers, students, pupils and enthusiasts thus have at their disposal tens of thousands of reference works in text mode, easily searchable at simple or advanced levels thanks to a full data mark-up and a powerful search engine. On our website you will find a detailed explanation of our editorial work and how we produce the databases, as well as additional information and documents. We warmly invite you to make a visit. summary literature, art and history Corpus of Medieval Literature from Its Origins to the End of the Fifteenth Century 6 Corpus of Narrative Literature from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century 8 Corpus of Early French-Speaking Sub-Saharan African Literature, Written and Oral from Its Origins to Independence (End of the 18th Century-1960) 9 Corpus of Early Speaking Literature From the Indian Ocean, Written and Oral, from the Origins to Independence (18th Century-1960) 10 Great Corpus of French and French-Speaking Literatures from the Middle Ages to the twentieth Century 11 The French Library 12 Corpus of Montaigne’s Works forthcoming 13 Corpus of Bayle’s Works new 14 Patrologia Græco-Latina 15 grammars, dictionaries and encyclopediae Corpus of French Renaissance Grammars 16 Corpus of French seventeenth Century Grammars 17 Corpus of Remarks -

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.Net

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.net Born to the nobility, the son of Abbo. Raised in the courts of Count Fulk II of Anjou and Duke William of Aquitaine. Received the Order of Tonsure at age nineteen. Canon of the church of Saint Martin of Tours. Studied music and theology in Paris for four years, studying under Remigius of Auxerre. Returning home, he spent years as a near-hermit in a cell, studying and praying. Benedictine monk at Baume, diocese of Besancon, France in 909, bringing all his worldly possessions – a library of about 100 books. Spiritual student of the abbot, Saint Berno of Cluny. Headmaster of the monastery school at Baume. Abbot of Baume in 924. Abbot of Cluny, Massey and Deols in 927. In 931, Pope John XI asked Odo to reform all the monasteries in the Aquitaine, northern France and Italy. Negotiated a peace between Heberic of Rome and Hugh of Provence in 936; returned twice in six years to renegotiate the peace between them. Persuaded many secular leaders to give up control of monasteries so they could return to being spiritual centers, not sources of cash for the state. Founded the monastery of Our Lady on the Aventine in Rome. Wrote a biography of Saint Gerald of Aurillac, three books of essays on morality, some homilies, an epic poem on the Redemption, and twelve choral antiphons in honour of Saint Martin of Tours. Noted for his knowledge, his administrative abilities, his skills as a reformer, and as a writer; also known for his charity, he has been depicted giving the poor the clothes off his back. -

Conductus and Modal Rhythm

Conductus and Modal Rhythm BY ERNEST H. SANDERS T HAS BEEN MORE THAN EIGHTY YEARS since Friedrich Ludwig (1872-193o), arguably the greatest of the seminal figures in twenti- eth-century musicology, began to publish his studies of medieval music. His single-handed occupation of the field, his absolute sover- eignty over the entire repertoire and all issues of scholarly significance arising from it, and his enormous, inescapably determinative influ- ence on the thinking of his successors, most of whom had studied with him, explain the epithet der Grossehe was given on at least one occasion.' Almost his entire professional energies were devoted to the music of the twelfth and, particularly, the thirteenth centuries, as well as to the polyphony of the fourteenth century, which he began to explore in depth in the 1920s. His stringent devotion to the facts and to conclusions supported by them was a trait singled out by several commentators.2 Ludwig's insistence on scholarly rigor, however, cannot be said to account completely for his Modaltheorie,which appeared to posit the applicability of modal rhythm to all music of the Notre Dame period-except organal style-and of the pre-Garlandian (or pre- Franconian) thirteenth century, including particularly the musical settings of poetry. Much of the pre-Garlandian ligature notation in thirteenth-century sources of melismatic polyphonic compositions of the first half of that century (clausulae, organa for more than two voices) and of melismatic portions of certain genres, such as the caudae of conducti,3 signifies modal rhythms, and the appropriatenessof the modal system cannot be disputed in this context. -

Three Centuries of French Medieval Music

THREE CENTURIES OF FRENCH MEDIEVAL MUSIC Downloaded from NEW CONCLUSIONS AND SOME NOTES. By AMEDEE GASTOUE LL the historians of our art admit that from about the third http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ quarter of the Xlth century till the corresponding quar- A ter of the XlVth century, it was French music which dictated its laws to Europe. Monks of Limoges and Discantus singers of Notre Dame de Paris, Troubadours of the South or Trouveres of the North, such were the first masters of French music, which was to enjoy such great influence in the artistic world of the Middle Ages. The few scholars who have studied t.liia epoch, so curious, at University of Iowa Libraries/Serials Acquisitions on May 28, 2015 have generally sought to specialise in one or other of the scientific branches implied by these researches: it is to such researches that must be attributed the merit of such general views as one can hope to be able to construct on this ground. But, it must be admitted, what each of these specialists has sought to deduce in his own sphere,—or indeed, the greater part of the general views, too hasty as to the conclusions, attempted so far, whatever may have been the merit of their authors,—cannot give an exact and precise idea of the development of our art at this period. I should like to contribute, therefore, by a few special points made in this study, to laying the foundations of a work which shall view the subject as a whole, a work of which I have been preparing the details for years, with a view to publishing later on the precious remains of French music of the Middle Ages. -

Petre Clemens—Lugentium Siccentur Motet in Honor of Clement VI

Petre clemens—Lugentium siccentur motet in honor of Clement VI Ivrea, Biblioteca Capitolare MS 115 Philippe de Vitry (1291–1361) fols. 37v–38 ed. Anna Zayaruznaya 5 + + + + [Triplum] [O. ] & ‚ – ‚‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ – ‚ ‚ ‚ Pe- tre cle - mens tam re quam no - mi‚ - ne cui‚‚ ‚ ‚ – nas-cen - + + [Motetus] [O. ] K K K K ‚ – ‚ & ‚‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ Lu - gen - ti - um sic - cen - tur o - cu‚ - + Tenor [ . ] V b O ‚ ‚ – ‚ ‚ – – – \ [Non\ est inventus] \ 10 + + K & – ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – ‚ ‚ ‚ ti Do - nan - tis dex - te - ra non de - fu - + + ‚ ‚ ‚ & – ‚. ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ ‚ – li, plau - dant se - nes,– ex - ul - tent par - vu - li, V b – – – – \ \ This edition is a companion to Anna Zayaruznaya, “Hockets as Compositional and Scribal Practice in the ars nova Motet—A Letter from Lady Music,” Journal of Musicology 30, no. 4 (2013): 461–501, and the text underlay has been subject to aggressive editorial intervention for reasons discussed there. It is not a diplomatic transcription, but rather an edition employing a simplified form of fourteenth-century French (ars nova) notation in score. Note-values have been left unreduced. Under the reigning mensuration (0. ) there are up to three minims (M) in each semibreve (S), up to three semibreves in each breve (B), and two breves in each long (L). When triple divisions of notes are involved, two processes occur in ars nova notation which do not happen in modern notation. In imperfec- tion, a smaller note “takes” value from a longer one so that the two together can add up to three beats. Thus MS MS denotes an iambic pattern, but if the minims were omitted the semibreves alone would have the value of three minims each (compare triplum and mote- tus in m. -

The Aquitanian Sacred Repertoire in Its Cultural Context

THE AQUITANIAN SACRED REPERTOIRE IN ITS CULTURAL CONTEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF PETRI CLA VIGER! KARl, IN HOC ANNI CIRCULO, AND CANTUMIRO SUMMA LAUDE by ANDREA ROSE RECEK A THESIS Presented to the School ofMusic and Dance and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2008 11 "The Aquitanian Sacred Repertoire in Its Cultural Context: An Examination ofPetri clavigeri kari, In hoc anni circulo, and Cantu miro summa laude," a thesis prepared by Andrea Rose Recek in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the School ofMusic and Dance. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Lori Kruckenberg, Chair ofth xamining Committee Committee in Charge: Dr. Lori Kruckenberg, Chair Dr. Marc Vanscheeuwijck Dr. Marian Smith Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 © 2008 Andrea Rose Recek IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Andrea Rose Recek for the degree of Master ofArts in the School ofMusic and Dance to be taken September 2008 Title: THE AQUITANIAN SACRED REPERTOIRE IN ITS CULTURAL CONTEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF PETRI CLA VIGER! KARl, INHOC ANNI CIRCULO, AND CANTU MIRa SUMMA LAUDE Approved: ~~ _ Lori Kruckenberg Medieval Aquitaine was a vibrant region in terms of its politics, religion, and culture, and these interrelated aspects oflife created a fertile environment for musical production. A rich manuscript tradition has facilitated numerous studies ofAquitanian sacred music, but to date most previous research has focused on one particular facet of the repertoire, often in isolation from its cultural context. This study seeks to view Aquitanian musical culture through several intersecting sacred and secular concerns and to relate the various musical traditions to the region's broader societal forces. -

Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant As Corporate Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2012 "Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge Jordan Timothy Ray Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Jordan Timothy Ray, ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jordan Timothy Ray Baker entitled ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

La Caccia Nell'ars Nova Italiana

8. Iohannes Tinctoris, Diffinitorium musice. Un dizionario Il corpus delle cacce trecentesche rappresenta con «La Tradizione Musicale» è una collana promossa di musica per Beatrice d’Aragona. A c. di C. Panti, 2004, ogni probabilità uno dei momenti di più intenso dal Dipartimento di Musicologia e Beni Culturali pp. LXXIX-80 e immediato contatto tra poesia e musica. La viva- dell’Università di Pavia, dalla Fondazione Walter 9. Tracce di una tradizione sommersa. I primi testi lirici italiani cità rappresentativa dei testi poetici, che mirano Stauffer e dalla Sezione Musica Clemente Terni e 19 tra poesia e musica. Atti del Seminario di studi (Cre mona, alla descrizione realistica di scene e situazioni im- Matilde Fiorini Aragone, che opera in seno alla e 20 febbraio 2004). A c. di M. S. Lannut ti e M. Locanto, LA CACCIA Fonda zione Ezio Franceschini, con l’intento di pro- 2005, pp. VIII-280 con 55 ill. e cd-rom mancabilmente caratterizzate dal movimento e dalla concitazione, trova nelle intonazioni polifo- muovere la ricerca sulla musica vista anche come 13. Giovanni Alpigiano - Pierluigi Licciardello, Offi - niche una cassa di risonanza che ne amplifica la speciale osservatorio delle altre manifestazioni della cium sancti Donati I. L’ufficio liturgico di san Do nato di cultura. «La Tradizione Musicale» si propone di of- portata. L’uso normativo della tecnica canonica, de- Arezzo nei manoscritti toscani medievali, 2008, pp. VIII-424 NELL’ARS NOVA ITALIANA frire edizioni di opere e di trattati musicali, studi 8 finita anch’essa ‘caccia’ o ‘fuga’, per l’evidente me- con ill. a colori monografici e volumi miscellanei di alto valore tafora delle voci che si inseguono, si dimostra 16. -

2-Voice Chorale Species Counterpoint Christopher Bailey

2-Voice Chorale Species Counterpoint Christopher Bailey Preamble In order to make the leap from composing in a 4-part chorale style to composing in a free- texture style, we will first re-think the process of composing chorales in a more contrapuntal manner. To this end, we will compose exercises in 2-voice (soprano and bass) Chorale Species Counterpoint. Species counterpoint is a way of studying counterpoint formulated by J.J. Fux (1660-1741) after the music of Palestrina and the Renaissance masters. Exercises in species were undertaken by many of the great composers--including Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and so forth. The basic idea is that one starts with simple, consonant, note-against-note counterpoint, and gradually attempts more and more elaborate exercises, involving more rhythmic complexity and dissonance, in constrained compositional situations. We will be learning a modified (simpler and freer) version of this, to fit in with the study of 4-part voice-leading and chorales, and tonal music in general. For each exercise, we will assume, at first, that one is given either a bass line, or a soprano line. Given either line, our first task is to compose the other line as a smooth counterpoint against the given line. With the possible exception of the cadence, we will not think about harmony and harmonic progression at all during this part of the process. We will think about line, and the intervals formed by the 2 voices. After the lines are composed in this way, only then do we go back and consider questions of harmony, and add the 2 inner voices to create a 4-voice chorale texture. -

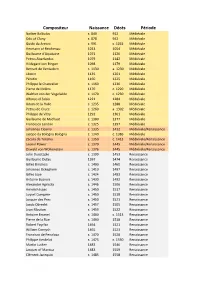

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 © Copyright by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain by Gillian Lucinda Gower Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Elizabeth Randell Upton, Chair This dissertation investigates the relational, representative, and most importantly, constitutive functions of sacred music composed on behalf of and at the behest of British queen- consorts during the later Middle Ages. I argue that the sequences, conductus, and motets discussed herein were composed with the express purpose of constituting and reifying normative gender roles for medieval queen-consorts. Although not every paraliturgical work in the English ii repertory may be classified as such, I argue that those works that feature female exemplars— model women who exemplified the traits, behaviors, and beliefs desired by the medieval Christian hegemony—should be reassessed in light of their historical and cultural moments. These liminal works, neither liturgical nor secular in tone, operate similarly to visual icons in order to create vivid images of exemplary women saints or Biblical figures to which queen- consorts were both implicitly as well as explicitly compared. The Iconography of Queenship is organized into four chapters, each of which examines an occasional musical work and seeks to situate it within its own unique historical moment. In addition, each chapter poses a specific historiographical problem and seeks to answer it through an analysis of the occasional work. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy.