The Victorian 1 Title of Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

In Memoriam COMPILED by GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN

In Memoriam COMPILED BY GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election Charles Buchanan Moncur Warren 1931 Hon. 1980 Janet Buchanan Carleton (Janet Adam Smith) LAC 1946 Hon. 1994 Geoffrey John Streetly ACG 1952 Stephen Paul Miller Asp. 1999 Frederic Sinclair Jackson 1957 Christine Bicknell LAC 1949 Sir George Sidney Bishop 1982 John Flavell Coa1es 1976 Robert Scott Russell 1935 A1istair Morgan 1976 Arun Pakmakar Samant 1987 In addition to the above eleven members who died in 1999, mention should be made of four further names. Jose Burman, a South African member, died in 1995 but was not included at the time. Ginette Harrison was the first woman to climb Kangchenjunga, in 1998. Whilst not yet a member, she had started the application process for membership. She died on Dhaulagiri last year. Yossi Brain, who sent us valuable reports from South America for the Area Notes, died in an avalanche on 25 September 1999 while mountain eering with friends in Northern Bolivia. Yossi touched the lives of a lot of people, through his lively, bright, and often irreverent sense of humourwhich permeated his guiding, his books, his articles and above all his spirit. He achieved a lot in the time he had, making two different and sucessful careers, and providing inspiration to many. Ulf Carlsson was Chairman of the Mountain Club of Kenya between 1993 and 1996. He wrote an article about the Swedish mountains for the 1997 Alpine Journal and was well known to some of our members. He died in the Pamir in 1999. Geoffrey Templeman 277 278 THE ALPINE JOURNAL 2000 Charles Warren, 1906-1999 Our Honorary Member Charles Warren, who died at Felsted a few days short of his 93rd birthday, was the oldest surviving member of the pre-war Everest expeditions. -

An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR Prof

ANGLICA An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR prof. dr hab. Grażyna Bystydzieńska [[email protected]] ASSOCIATE EDITORS dr hab. Marzena Sokołowska-Paryż [[email protected]] dr Anna Wojtyś [[email protected]] ASSISTANT EDITORS dr Katarzyna Kociołek [[email protected]] dr Magdalena Kizeweter [[email protected]] ADVISORY BOARD GUEST REVIEWERS Michael Bilynsky, University of Lviv Dorota Babilas, University of Warsaw Andrzej Bogusławski, University of Warsaw Teresa Bela, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Mirosława Buchholtz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Maria Błaszkiewicz, University of Warsaw Xavier Dekeyser University of Antwerp / KU Leuven Anna Branach-Kallas, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Bernhard Diensberg, University of Bonn Teresa Bruś, University of Wrocław, Poland Edwin Duncan, Towson University, Towson, MD Francesca de Lucia, independent scholar Jacek Fabiszak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ilona Dobosiewicz, Opole University Jacek Fisiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Andrew Gross, University of Göttingen Elzbieta Foeller-Pituch, Northwestern University, Evanston-Chicago Paweł Jędrzejko, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec Piotr Gąsiorowski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Aniela Korzeniowska, University of Warsaw Keith Hanley, Lancaster University Andrzej Kowalczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Christopher Knight, University of Montana, Missoula, MT Barbara Kowalik, University of Warsaw Marcin Krygier, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ewa Łuczak, University of Warsaw Krystyna Kujawińska-Courtney, University of Łódź David Malcolm, University of Gdańsk Zbigniew Mazur, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Dominika Oramus University of Warsaw Znak ogólnodostępnyRafał / Molencki,wersje University językowe of Silesia, Sosnowiec Marek Paryż, University of Warsaw John G. Newman, University of Texas at Brownsville Anna Pochmara, University of Warsaw Michal Jan Rozbicki, St. -

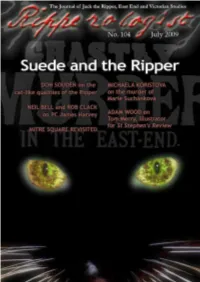

Mitre Square Revisited News Reports, Reviews and Other Items Are Copyright © 2009 Ripperologist

RIPPEROLOGIST MAGAZINE Issue 104, July 2009 QUOTE FOR JULY: Andre the Giant. Jack the Ripper. Dennis the Menace. Each has left a unique mark in his respective field, whether it be wrestling, serial killing or neighborhood mischief-making. Mr. The Entertainer has similarly ridden his own mid-moniker demonstrative adjective to the top of the eponymous entertainment field. Cedric the Entertainer at the Ryman - King of Comedy Julie Seabaugh, Nashville Scene , 30 May 2009. We would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance given by Features the following people in the production of this issue of Ripperologist: John Bennett — Thank you! Editorial E- Reading The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed Paul Begg articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist are those of the authors and do not necessarily Suede and the Ripper reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Ripperologist or Don Souden its editors. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Hell on Earth: The Murder of Marie Suchánková - Ripperologist and its editorial team. Michaela Kořistová We occasionally use material we believe has been placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of some - City Beat: PC Harvey thing we have published we will be pleased to make a prop - Neil Bell and Robert Clack er acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. 104 July 2009, including the co mpilation of al l materials and the unsigned articles, essays, Mitre Square Revisited news reports, reviews and other items are copyright © 2009 Ripperologist. -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

Suspects Information Booklet

Metropolitan Police Cold Case Files Case: Jack the Ripper Date of original investigation: August- December 1888 Officer in charge of investigation: Charles Warren, Head of metropolitan police After a detailed and long investigation, the case of the Jack the Ripper murders still has not been solved. After interviewing several witnesses we had a vague idea of what Jack looked like. However, there were many conflicting witness reports on what Jack looked like so we could not be certain. Nevertheless, we had a list of suspects from the witness reports and other evidence left at the scene. Unfortunately, there was not enough evidence to convict any of the suspects. Hopefully, in the future someone can solve these horrendous crimes if more information comes to light. Therefore, the investigation team and I leave behind the information we have on the suspects so that one day he can be found. Charles Warren, Head of the Metropolitan Police Above: The Investigation team Left: Charles Warren, Head of the Metropolitan Police Montague John Druitt Druitt was born in Dorset, England. He the son of a prominent local surgeon. Having received his qualifications from the University of Oxford he became a lawyer in 1885. He was also employed as an assistant schoolmaster at a boarding school in Blackheath, London from 1881 until he was dismissed shortly before his death in 1888. His body was found floating in the river Thames at Chiswick on December 31, 1888. A medical examination suggested that his body was kept at the bottom of the river for several weeks by stones places in their pockets. -

Paper 1: Historic Environment Whitechapel, C1870 – C1900: Crime

Paper 1: Historic environment Whitechapel, c1870 – c1900: Crime, policing and the inner city Name: Teacher: Form: Sources Questions 1 and 2 of Paper 1 will focus on your ability to use source materials with questions 2 (a) and 2 (b) asking specifically about the utility and usefulness of source materials. When handling a source you must consider the following: Content – Nature – Origins – Purpose – Then once you’ve considered all of those things you must do a CAT test! The CAT (or the Pandora test) Is it Comprehensive? Is it Accurate? Is it Typical? When you give a CAT test score the score is out of nine because…. Types of source You will handle sources which tell you lots of different things but the types of sources have lots of commonalities, think about the strengths and weaknesses for each source type. Source Strengths Weaknesses National newspaper Police records Surveys Cartoons Local newspapers Government records Census records Photographs Crime statistics Diaries Individuals reports e.g. Charles Booth Maps Which type of source would be the most useful when looking into people’s opinions? Following up sources Not only will you be asked to consider the value of a source but you will also be asked to think about how an historian would use a source. How does an historian know What questions do historians ask? they’re right? What types of sources do Why would a CAT be useful to historians use? an historian? What does an historian always know? What makes a source useful? Sort the words into the bags, which relate to a source that is useful or limited? When is a source is limited does it mean you can’t use it? What was Whitechapel like? Whitechapel is an area of London’s East End, just outside the City of London. -

The Final Solution (1976)

When? ‘The Autumn of Terror’ 1888, 31st August- 9th November 1888. The year after Queen Victoria’s Golden jubilee. Where? Whitechapel in the East End of London. Slum environment. Crimes? The violent murder and mutilation of women. Modus operandi? Slits throats of victims with a bladed weapon; abdominal and genital mutilations; organs removed. Victims? 5 canonical victims: Mary Ann Nichols; Annie Chapman; Elizabeth Stride; Catherine Eddowes; Mary Jane Kelly. All were prostitutes. Other potential victims include: Emma Smith; Martha Tabram. Perpetrator? Unknown Investigators? Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson; Inspector Frederick George Abberline; Inspector Joseph Chandler; Inspector Edmund Reid; Inspector Walter Beck. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Commissioner of the City of London Police, Sir James Fraser. Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan CID, Sir Robert Anderson. Victim number 5: Victim number 2: Mary Jane Kelly Annie Chapman Aged 25 Aged 47 Murdered: 9th November 1888 Murdered: 8th September 1888 Throat slit. Breasts cut off. Heart, uterus, kidney, Throat cut. Intestines severed and arranged over right shoulder. Removal liver, intestines, spleen and breast removed. of stomach, uterus, upper part of vagina, large portion of the bladder. Victim number 1: Missing portion of Mary Ann Nicholls Catherine Eddowes’ Aged 43 apron found plus the Murdered: 31st August 1888 chalk message on the Throat cut. Mutilation of the wall: ‘The Jews/Juwes abdomen. No organs removed. are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ Victim number 4: Victim number 3: Catherine Eddowes Elizabeth Stride Aged 46 Aged 44 th Murdered: 30th September 1888 Murdered: 30 September 1888 Throat cut. Intestines draped Throat cut. -

Blandford Stroll 4 Historical Town

BLANDFORD STROLL 4 5 6 4 HISTORICAL TOWN 3 2 7 STOUR CROWN MEADOWS MEADOWS 1 DURATION: 1¼ miles TERRAIN: Suitable for all With grateful thanks to Blandford Rotary for sponsoring the printing of these walk guides. Thanks also to the North Dorset Rangers, Blandford Civic Society, Dorset History Centre, Blandford Library, Lorna for her IT expertise, Pat for her photos, Liz (Town Guide) for her local knowledge, Adam for his technical support and all the guinea-pigs who tried them out and improved them. evident. down Damory Street and you will soon find yourself in 1 Turn right out of the TIC . After about 50 yards East Street. Turn left here (Wimborne Road), cross 3 You are now on the corner of Whitecliff Mill cross the road and look at the information panel Damory Court Street and walk about 100 yards to St. situated at the entrance to River Mews . Street. Cross it to Salisbury Street; cross it and go uphill Leonard’s Avenue. Cross the road and next to the fire- During WW2 there was much concern that, should the (right-hand pavement) to the Ryves Alms Houses. station take the footpath to St. Leonard’s Chapel, about Germans land on the south coast, there would be little Ryves Alms Houses were built for ten elderly people of 100 yards, on the right. to stop their rapid advance inland. Blandford’s strategic the town in 1682, one of the few buildings to escape the The signboard will tell you about this leper hospital position at the first significant crossing-point of the Fire (thanks to tiles rather than thatch). -

Press Releases Unique Crime Collection Giving Insight Into

Unique crime collection giving insight into Whitechapel murders to be made public for the first time The unique personal archive of the detective who led the hunt for Jack the Ripper - including a book in which he names the infamous Whitechapel murderer - will be made public for the first time after being given into the care of an independent museum. The private collection of Metropolitan Police Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson has been entrusted to the National Emergency Services Museum (NESM) in Sheffield by the former detective's family. The treasure trove lay undiscovered for decades until Swanson's descendants discovered an enormous collection of over 150 individual objects; paperwork, photographs, letters, drawings and personal belongings. Among them was what became known as 'the Swanson marginalia'; a book, annotated by Swanson, in which he names the person he believed to be the infamous killer, Jack the Ripper. The marginalia is thought to be a unique artefact revealing unknown details of the case as well as theories and notes on what evidence the Metropolitan Police had gathered - all from the pen of the inspector charged with solving the case. The marginalia, along with other items from the collection, will form part of a new exhibition, Daring Detectives & Dastardly Deeds, which will be revealed to visitors when the museum reopens on Wednesday 19 May. The exhibition, housed within NESM's original Victorian cells, explores the intriguing history of 19th crime and punishment from the bobby on the beat to the emerging science of forensics. The Swanson collection is thought to be one of the most detailed and significant of its kind. -

In Whitechapel a Blow by Blow Account from J.G

Cousin THE CASEBOOK Lionel’s Life Enter The Matrix and Career D. M. Gates and Adam Went Jeff Beveridge issue six February 2011 CK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY FRIDAY THE 13TH! in Whitechapel a blow by blow account from J.G. Simons and Neil Bell Did George Sims LOSE IT? Jonathan Hainsworth investigates THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 6 February 2011 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue six signed articles, essays, letters, reviews February 2011 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may CONTENTS: be reproduced, stored in a retrieval Refer Madness pg 3 On The Case system, transmitted or otherwise cir- culated in any form or by any means, Melville Macnaghten Revisited News From Ripper World pg 115 including digital, electronic, printed, Jonathan Hainsworth pg 5 On The Case Extra mechanical, photocopying, recording or Feature Stories pg 117 Tom Sadler “48hrs” any other, without the express written J.G. Simons and Neil Bell pg 29 On The Case Puzzling permission of Casebook.org. The unau- “Cousin Lionel” Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 123 thorized reproduction or circulation of Adam Went pg 48 Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, The 1888 Old Bailey and Press Wolverhampton pg 125 whether for monetary gain or not, is Criminal Matrix CSI: Whitechapel strictly prohibited and may constitute D. M. Gates and Jeff Beveridge pg 76 Miller’s Court pg 130 copyright infringement as defined in domestic laws and international agree- Undercover Investigations From the Casebook Archives Book Reviews pg 87 Matthew Packer pg 138 ments and give rise to civil liability and criminal prosecution.