Machu Picchu Between Conservation and Exploitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley — Lima, Cusco, Machu Picchu, Sacred Valley of the Incas — TOUR DETAILS Machu Picchu & Highlights The Sacred Valley • Machu Picchu • Sacred Valley of the Incas • Price: $1,995 USD • Vistadome Train Ride, Andes Mountains • Discounts: • Ollantaytambo • 5% - Returning Volant Customer • Saqsaywaman • Duration: 9 days • Tambomachay • Date: Feb. 19-27, 2018 • Ruins of Moray • Difficulty: Easy • Urumbamba River • Aguas Calientes • Temple of the Sun and Qorikancha Inclusions • Cusco, 16th century Spanish Culture • All internal flights (while on tour) • Lima, Historic Old Town • All scheduled accommodations (2-3 star) • All scheduled meals Exclusions • Transportation throughout tour • International airfare (to and from Lima, Peru) • Airport transfers • Entrance fees to museums and other attractions • Machu Picchu entrance fee not listed in inclusions • Vistadome Train Ride, Peru Rail • Personal items: Laundry, shopping, etc. • Personal guide ITINERARY Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley - 9 Days / 8 Nights Itinerary - DAY ACTIVITY LOCATION - MEALS Lima, Peru • Arrive: Jorge Chavez International Airport (LIM), Lima, Peru 1 • Transfer to hotel • Miraflores and Pacific coast Dinner Lima, Peru • Tour Lima’s Historic District 2 • San Francisco Monastery & Catacombs, Plaza Mayor, Lima Cathedral, Government Palace Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Ollyantaytambo, Sacred Valley • Morning flight to Cusco, The Sacred Valley of the Incas 3 • Inca ruins: Saqsaywaman, Rodadero, Puca Pucara, Tambomachay, Pisac • Overnight: Ollantaytambo, Sacred -

Qhapaq Ñan (Chemin Principal Andin) Au Qollasuyu Paysage, Morphologie Et Patrimoine Linéaire 2 Remerciements

ANNÉE ACADÉMIQUE 2011-2012 DENIS PIRON FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES APPLIQUÉES TRAVAIL DE FIN D’ÉTUDES RÉALISÉ EN VUE DE L’OBTENTION DU GRADE DE MASTER INGÉNIEUR CIVIL EN ARCHITECTURE UNIVERSITÉ DE LIÈGE QHAPAQ ÑAN (CHEMIN PRINCIPAL ANDIN) AU QOLLASUYU PAYSAGE, MORPHOLOGIE ET PATRIMOINE LINÉAIRE 2 REMERCIEMENTS La réalisation de ce travail, qui s’inscrit dans le cadre de la coopération au développement, a nécessité un voyage de trois mois dans la région de Cusco, au Pérou. Le voyage réalisé dans le cadre du présent travail a été rendu possible grâce à l’intervention financière du Conseil interuniversitaire de la Communauté française de Belgique - Commission universitaire pour le Développement - Rue de Namur, 72-74, 1000 Bruxelles - www.cud.be. Je remercie tout d’abord mon promoteur, monsieur Jacques Teller, pour m’avoir proposé un sujet si original et passionnant, pour m’avoir permis d’aller m’ouvrir l’esprit dans un pays aussi magnifique que dépaysant. Je suis également reconnaissant envers les autres membres de mon jury, messieurs Pierre Paquet, Jean-Claude Cornesse et Jean Stillemans qui ont bien voulu s’intéresser à mon travail. Je remercie aussi Marta Vilela Malpartida pour son accueil à Lima ; Sonia Martina Herrera Delgado pour le support qu’elle m’a apporté à Cusco ; tout particulièrement le South American Explorer’s Club grâce à qui j’ai pu loger et nouer des contacts à Cusco ; Elisabeth Schumaker, Elise Neola May, Paolo Greer ; sans oublier les péruviens de Cusco et des campagnes pour leur gentillesse et leur sociabilité. Merci à ma famille pour m’avoir toujours encouragé à me lancer dans les projets les plus fous, et particulièrement ma soeur Julie qui m’a apporté de ses compétences géographiques, ainsi que ma grand-mère pour m’avoir relu et conseillé dans la rédaction. -

SACRED VALLEY SINGLETRACK | MULTI-DAY TOUR Details & Pricing 3 DAYS | TRAIL RATING – DIFFICULT |630 – 895 USD Per Rider

SACRED VALLEY SINGLETRACK | MULTI-DAY TOUR Details & Pricing 3 DAYS | TRAIL RATING – DIFFICULT |630 – 895 USD per rider HIGHLIGHTS_ DAY 1 Best of Lamay DAY 2 Huchuy Qosqo Inca DAY 3 Patacancha Enduro ✓ Start a ride at 14,375 ft Lamay is one of the sleepiest Fort Pack your pedaling legs. A flowy and often rocky Enduro ✓ 22,600 ft of descents towns in the Sacred Valley, yet Today’s ride features a 2,000 ft racecourse that descends from ✓ 57 miles of singletrack home to the rowdiest rides in climb to our summit! Ride to an the heights of the Patacancha ✓ Ancient 800-year-old trails all of South America! Shuttle immense fortress with the best Valley to the Inca town of ✓ Peru’s world-class food and ride 3 unreal singletracks views of The Sacred Valley. Ollantaytambo. Please brake and culture and finish the day in the guinea Enjoy barbecue and brews back for alpacas! Finish the day at ✓ Good times with a fun- pig capitol of the world! (Night: at the lodge. (Night: The Sacred our favorite local brewery. loving team of guides The Sacred Valley) Valley) (Night: Lodging Not Included) ✓ Charming lodging in The Dist: 26.0 mi 1,120 ft Dist: 13.5 mi 3,812 ft Dist: 17.8 mi 1,168 ft Sacred Valley 9,830 ft Max: 13,985 ft 6,719 ft Max: 14,160 ft 6,042 ft Max. 14,375 ft www.perubiking.com WHAT’S INCLUDED PRICING ✓ 2017 YT CAPRA AL Enduro Mountain Bike Rental All Multi-Day Rides are organized in private groups to assure ✓ Helmet, Knee & Elbow Pads, and Gloves the best experience for riders. -

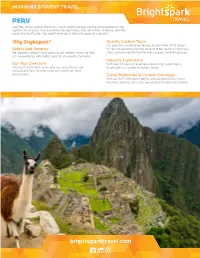

Brightsparktravel.Com SAMPLE ITINERARY ®

INSPIRING STUDENT TRAVEL ® PERU Journey to the land of the Incas. Savor world-famous cuisine while exploring the capital city of Lima, Cusco and the Sacred Valley, the salt mines at Maras, and the iconic Machu Picchu. You might even get a llama to pose for a photo! Why Brightspark? Quality, Custom Tours Our programs are designed for you, by you. From STEM-based Safety And Security DC tours to performance trips to some of our country’s top music We regularly conduct strict audits of our vendors, ensuring they cities, we have a destination for every budget and every passion. act in accordance with safety, security, and quality standards. Industry Experience Our Tour Directors With over 50 years of experience providing custom tours, You deserve the best, so we only use experienced and Brightspark is a leader in student travel. enthusiastic Tour Directors who are experts on their destinations. Travel Protection & Incident Coverage With our 24/7 emergency hotline and comprehensive travel insurance options, we’ve got you covered at home and abroad. brightsparktravel.com SAMPLE ITINERARY ® PERU Day 1: Board your flight to Perú. Day 5: Ollantaytambo • Meet your Tour Director at Jorge Chávez International Airport. • Embark upon a guided tour of Ollantaytambo, an Andean • Board your private motor coach and settle into your hotel. village in the Sacred Valley and the gateway to the Antisuyo, the Amazon section of the Inca Empire. The town retains its original Day 2: Lima Inca street layout. Visit the ruins of the fortress, one of the only • Meet your guide for a walking tour of the Peruvian capital. -

Pscde3 - the Four Sides of the Inca Empire

CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. Manco Cápac 515 – Wanchaq Ca. M. M. Izaga 740 Of. 207 - Chiclayo www.chaskiventura.com T: 51+ 84 233952 T: 51 +74 221282 PSCDE3 - THE FOUR SIDES OF THE INCA EMPIRE SUMMARY DURATION AND SEASON 15 Days/ 14 Nights LOCATION Department of Arequipa, Puno, Cusco, Raqchi community ATRACTIONS Tourism: Archaeological, Ethno tourism, Gastronomic and landscapes. ATRACTIVOS Archaeological and Historical complexes: Machu Picchu, Tipón, Pisac, Pikillaqta, Ollantaytambo, Moray, Maras, Chinchero, Saqsayhuaman, Catedral, Qoricancha, Cusco city, Inca and pre-Inca archaeological complexes, Temple of Wiracocha, Arequipa and Puno. Living culture: traditional weaving techniques and weaving in the Communities of Chinchero, Sibayo, , Raqchi, Uros Museum: in Lima, Arequipa, Cusco. Natural areas: of Titicaca, highlands, Colca canyon, local fauna and flora. TYPE OF SERVICE Private GUIDE – TOUR LEADER English, French, or Spanish. Its presence is important because it allows to incorporate your journey in the thematic offered, getting closer to the economic, institutional, and historic culture and the ecosystems of the circuit for a better understanding. RESUME This circuit offers to get closer to the Andean culture and to understand its world view, its focus, its technologies, its mixture with the Hispanic culture, and the fact that it remains present in Indigenous Communities today. In this way, by bus, small boat, plane or walking, we will visit Archaeological and Historical Complexes, Communities, Museums & Natural Environments that will enable us to know the heart of the Inca Empire - the last heir of the Andean independent culture and predecessor of the mixed world of nowadays. CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. -

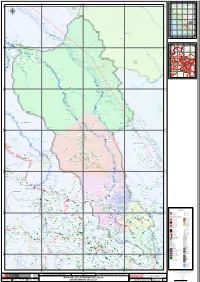

Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ

81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W 800000 820000 840000 ° ° 0 0 R 0 í 0 o 0 C 0 COLOMBIA a 0 l 0 l a n 0 0 ECUADOR Victoria g a 2 2 6 Sacramento Santuario 6 8 8 S S 560 Nacional ° ° Esmeralda Megantoni 3 3 TUMBES LORETO PIURA AMAZONAS S S ° ° R 6 LAMBAYEQUECAJAMARCA BRASIL 6 ío 565 M a µ e SAN MARTIN Quellouno st ró Trabajos n LA LIBERTAD Rosario S S Bellavista ° ° 9 ANCASH 9 HUANUCO UCAYALI 570 PASCO R Mesapata 1 ío P CUSCO a u c Monte Cirialo a Ocampo r JUNIN ta S S m CALLAOLIMA ° b ° o MADRE DE DIOS 2 2 1 Rí CUSCO 1 Paimanayoc o M ae strón HUANCAVELICA OCÉANO PACÍFICO Chaupimayo AYACUCHOAPURIMAC 575 ICA PUNO S S Mapitonoa ° ° Chaupichullo Lacco 1 5 5 Qosqopata Quellomayo 1 1 Emp. CU-104. Mameria AREQUIPA Llactapata MOQUEGUA Huaynapata Emp. CU-104. Miraflores MANU Alto Serpiyoc. BOLIVIA S S TACNA Cristo Salvador Achupallayoc ° Emp. CU-698 ° Larco 580 8 8 Emp. CU-104. 1 1 Quesquento Alto. Yanamayo CU Limonpata CU «¬701 81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W CU Campanayoc Alto Emp. CU-698 Chunchusmayo Ichiminea «¬695 Kcarun 693 Antimayo «¬ Dos De Mayo Santa Rosa Serpiyoc Cerpiyoc Serpiyoc Alto Mision Huaycco Martinesniyoc San Jose de Sirphiyoc Emp. CU-694 (Serpiyoc) CU Emp. CU-696 CU Cosireni Paititi Quimsacocha Emp. CU-105 (Chancamayo) 694 Limonpata Santa C¬ruz 698 Emp. CU-104 585 R « R ¬ « Emp. CU-104 (Lechemayo). í ío CU o U Ur ru ub 697 Emp. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Climb the Highest Mountain in Africa…

Trek the ancient Inca Trail in Peru to… Machu Picchu …for a trip of a life time! – 2022 Trip outline The Inca Trail is Peru's best known hike, combining a stunning combination of Inca ruins, magnificent mountains and exotic vegetation. The trail goes over high mountain passes with unforgettable views, through the rainforest, and finally into subtropical vegetation. The legendary Inca Trail takes you through the diverse wilderness of the Machu Picchu Historical Sanctuary, passing numerous Inca ruins on the magnificent stone highway before descending to the famed citadel of Machu Picchu. The 45 km trek is covered in 4 days, arriving at Machu Picchu at daybreak on the final day before returning to Cusco by train in the afternoon. The trek is rated moderate and any reasonably fit person will be able to cover the route. It is fairly challenging nevertheless, you will be carrying your own personal equipment (porters carry group equipment including tents, stoves and food etc…) and altitudes of 4200m are reached. We allow 2 full days in Cusco prior to commencing the trek in order to help you acclimatize sufficiently and give you an opportunity to visit the city of Cusco and near by Inka ruins at Sacsayhuaman, Q'enko, Pucapucara and Tambomachay. Your trip departs from London Heathrow where you’ll fly to Lima or Bogota (depending on flight arrangements) and onward to Cusco (Peru). The Amaru Hotel or similar (3/4 star) will be your base for the next few days while you acclimatise to Peru’s high altitude and prepare for the Inca trek ahead. -

Plan Copesco

GOBIERNO REGIONAL CUSCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO PLAN ESTRATEGICO INSTITUCIONAL 2007 -2011. CUSCO – PERÚ SETIEMBRE 2007 1 GOBIERNO REGIONAL CUSCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO INTRODUCCION En la década de 1960, a solicitud del Gobierno Peruano el PNUD envió misiones para la evaluación de las potencialidades del País en materia de desarrollo sustentable, resultado del cual se priorizó el valor turístico del Eje Cusco Puno para iniciar las acciones de un desarrollo sostenido de inversiones. Sobre la base de los informes Técnicos Vrioni y Rish formulados por la UNESCO y BIRF en los años 1965 y 1968 COPESCO dentro de una perspectiva de desarrollo integral implementa inicialmente sus acciones en la zona del Sur Este Peruano sobre el Eje Machupicchu Cusco Puno Desaguadero. Los años que represente el trabajo regional del Plan COPESCO han permitido el desarrollo de esta actividad. Una de las experiencias constituye el Plan de Desarrollo Turístico de la Región Inka 1995-2005, elaborado por el Plan Copesco por encargo del Gobierno Regional, instrumento de gestión que ha permitido el desarrollo de la actividad turística en la última década, su política también estuvo orientado al desarrollo turístico por circuitos turísticos identificados, El Plan Estratégico Nacional de Turismo- PENTUR 2005-2015, considera que el turismo es la segunda actividad generadora de divisas, y su vez es la actividad prioritaria del Gobierno para el periodo 2005. Este Plan Estratégico se circunscribe en las funciones y lineamientos del MINCETUR, Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Regional Concertado. CUSCO AL 2012, los Planes Estratégicos Provinciales y específicamente en las funciones y objetivos del PER Plan COPESCO, unidad ejecutora del Gobierno Regional Cusco: las que se pueden traducir en la finalidad de ampliar y diversificar la oferta turística en el contexto Regional. -

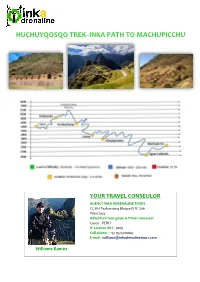

Huchuyqosqo Trek–Inka Path to Machupicchu

HUCHUYQOSQO TREK–INKA PATH TO MACHUPICCHU YOUR TRAVEL CONSEULOR AGENCY INKA ADRENALINE TOURS CC.HH Pachacuteq Bloque D N° 206 Wanchaq Adventure tour guide & travel conseulor Cusco - PERU N° Licence DRT : 3019 Cell phone : +51 951506969 E-mail : [email protected] Williams Ramos Programs designed for lovers of Middle Mountain, challenged the highest points of the Andes enjoy the snowcapped mountains of the Vilcabamba range hiking to the residence of the eighth emperor Inca “Wiracocha” and The lost City of the Incas Machupicchu, a Trek wrapped in landscape nature and history. DAY 01: CUSCO - PATABAMBA – HUCHUYQOSQO We leave Cusco early, and take private transport to the village of Patabamba in approximately 1 ½ from this point we star hiking, using the Inca trail going to Huchuy Qosqo, this trail had been used since the Inca´s time, during the day we cross the highest of which is Patabamba Pass (4100m/14300ft), this an interesting view of point where we can see the snowcapped mountains of Vilcanota Range, after a break we continuing but this time descending steps of this Inca trail to arrive to Huchuy Qosqo (3550m/11646ft) in this place we have the opportunity to pass the night in a local house Family where we can share tradition and culture. Bus Travel Time: 1 ½ hours Approximate Walking Time: 7 hours Approximate walking distance: 11 kms Difference of height: 3762-4393 Patabamba Pass -3550m DAY 02: HUCHUY QOSQO – PISAC - OLLANTAYTAMBO – AGUAS CALIENTES After the breakfast, we continuing with the hike 2 hours of a descending -

Course Description Famous for the Inka Site of Machu Picchu, Peru

University of South Dakota Faculty Led Program- Summer 2017 Peruvian Archaeology: The Inkas and their Ancestors (ANTH 490) Course Description Famous for the Inka site of Machu Picchu, Peru has a fascinating prehistory that goes deeper in time from the origins of animal and plant domestication to the development of early states like the Moche and the Wari. This course is a survey of the ancient cultures and main archaeological sites of the central Andes including Chavín de Huántar and its religious center, Nazca and its famous lines, Huacas de Moche and its hyper- realistic ceramics, Huari and Pikillaqta and their high walled compounds, Chan Chan and its adobe citadel, and Macchu Picchu and Sacsayhuaman and their fine stone architecture. Topics will include the origins of plant and animal domestication, ceremonial and domestic architecture, ritual and religion, and the formation of state and empires. While we will mainly discuss the material culture (architecture, ceramics, human and animal bones, stone tools) excavated from archaeological sites ethnohistoric and ethnographic sources (maps, manuscripts, drawings, folklore, oral traditions) will also be incorporated when appropriate. The course will also include guided visits to museums and archaeological sites in and nearby Lima. Learning outcomes After taking this course students should be familiar with the sites, chronology, and major debates of Peruvian archaeology and more specifically, they should be able to: Describe the ecological diversity and the adaptation of the diverse prehispanic cultures of Peru Explain the origins of agriculture, animal domestication, and social complexity- including states and empires that took place in Prehispanic Peru. Identify some of the material culture of the most recognizable prehispanic groups of Peru Demonstrate spatial and chronological knowledge of the Prehispanic cultures of Peru.