National Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

AFGHANISTAN Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) (January - March 2019)

AFGHANISTAN Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) (January - March 2019) 146 organisations Darwaz-e-Payin UZBEKISTAN Shaki TAJIKISTAN Delivering humanitarian services in Kofab Khwahan January, February and March 2019. Darwaz-e-Balla Raghestan Shighnan Chahab Yawan Yangi Qala Arghanj Darqad Shahr-e-Buzorg Kohistan Khwah CHINA Qarqin Shortepa Yaftal-e-Sufla Khamyab Dasht-e-Qala Wakhan TURKMENISTAN Khan-e-Char Mardyan Fayzabad Sharak-e-Hayratan Kaldar Shuhada Bagh Imam Sahib ! Qurghan Mingajik Dawlat Abad Rostaq Argo Baharak Khwaja Dukoh Khwaja Andkhoy Khulm Dasht-e-Archi Ghar Hazar Khash Warduj JAWZJAN Balkh Qala-e-Zal Sumuch Qaram Qul Fayzabad Char Nahr-e-Shahi KUNDUZ Darayem Kunduz Khan Baharak Kalafgan Khanaqa Bolak Abad Eshkashem Mazar-e-Sharif ! ! Keshem Jorm ! ! Teshkan Chahar Darah Taloqan Shiberghan Aqcha Dehdadi Ali Dawlat Abad Bangi Chemtal Abad TAKHAR Marmul Namak Ab BADAKHSHAN Feroz Yamgan NUMBER OF REPORTING ORGANISATIONS BY CLUSTER Chal Farkhar Tagab BALKH Nakhchir Charkent Zebak Shirin Tagab Sar-e-Pul Hazrat-e-Sultan Eshkmesh Qush ! Sholgareh ! Baghlan-e-Jadid Tepa Aybak Burka Guzargah-e-Nur Khwaja Sayad Keshendeh Fereng Almar Sabz Posh SAMANGAN Warsaj Darzab Sozmaqala Wa Gharu ! Khuram Wa Pul-e-Khumri Nahrin Khwaja Ghormach Maymana Dara-e-Suf-e-Payin ! Bilcheragh Gosfandi Sarbagh Hejran Khost Wa Koran Wa Pashtun Kot Fereng Monjan ! Sancharak Zari ! ! ! Dara-e-Suf-e-Bala BAGHLAN Barg-e-Matal ! Qaysar FARYAB ! Deh Salah ! Dahana-e-Ghori ! Garzewan ! ! ! Ruy-e-Duab Paryan ! ! Bala Murghab Kohestanat ! Andarab Pul-e-Hisar ! -

The ANSO Report (16-31 January 2011)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 66 16-31 January 2011 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2 The targeting of military and less than the 60% growth While the circumstances 6 Northern Region political leadership by both noted in the January 2009- surrounding the murder of Western Region 11 sides of the conflict was a 2010 rate comparison. a female NGO staff mem- regular feature of reporting in While this can be attributed ber in Parwan this period Eastern Region 14 2010. Early indicators sug- to a variety of factors, the remain unclear, it does Southern Region 19 gest that this year will follow key variables are the sus- mark the first casualty for in a similar vain, supported tained IMF/ANSF opera- the community this year. 24 ANSO Info Page by the killing of the Kanda- tional levels over the past As well, it accounts for the har Deputy Provincial Gov- few months as well as the first NGO incident to oc- ernor (IED strike) this pe- ‘saturation’ that has been cur outside of the North. YOU NEED TO KNOW riod. This incident also reached in many of the key Last year, this region ac- marks the most senior local contested areas. Nonethe- counted for over 40% of • Targeting of the political & official hit since the death of less, the January figures all NGO incidents, and military leadership by both parties of the conflict the Kunduz Provincial Gov- provides a glimpse into the January figures are sugges- ernor in October of last year. -

Conflict-Induced Internal Displacement—Monthly Update

CONFLICT-INDUCED INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT—MONTHLY UPDATE UNHCR AFGHANISTAN DECEMBER 2012 HIGHLIGHTS IDPs (Internally Displaced Total Increase Decrease Overall change Total displaced as at Total recorded Persons) are persons or 30 November 2012 December 2012 December 2012 December 2012 31 December 2012 in 2012 groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or leave their homes or 481,877 4,450 29 4,421 486,298 203,457 places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of, or in order to, avoid the effects • IDPs overall: As at 31 December, 486,298 persons (76,335 families) are internally dis- of armed conflict, situations placed due to conflict in Afghanistan. of generalized violence, • violations of human rights or December 2012 : 4,450 individuals (830 families) have been newly recorded as displaced natural or human-made due to conflict of whom 180 individuals (4%) were displaced in December, while 587 indi- disasters, and who have not viduals (13%) were displaced in November and 341 individuals (8%) were displaced in crossed an internationally recognized State border ( UN October 2012. The remaining 3,342 individuals (75%) were displaced prior to October Secretary General, Guiding 2012. Principles on Internal Dis- • Overall in 2012 : Since January 2012, a total of 203,457 conflict-induced IDPs have been placement, E/CN.4/1998/53/ Add.2, 11 February 1998). recorded in Afghanistan. This figure includes 94,299 conflict-induced IDPs (46%) who were displaced in 2012 whereas 109,158 (54%) individuals were displaced prior to 2012. DISPLACEMENT TRENDS BY REGION No new displacement was recorded in the South and Central regions as well as Region end-Nov 2012 Increase Decrease end-Dec 2012 in the Central Highlands. -

Situation Analysis of the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Sector in Relation to the Fulfilment of the Rights of Children and Women in Afghanistan, 2013

WASH Components of the Situation Analysis of Children and Women, Afghanistan, 2013 Situation Analysis of the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Sector in Relation to the Fulfilment of the Rights of Children and Women in Afghanistan, 2013 Final - 31 Aug 2013 Reductions in manifestations of Children and women attain Access to deprivation their human rights improved water and Reduced U5 mortality Right to water and sanitation sanitation and Reduced maternal mortality Rights to life, health and practice of Access to quality primary dignity good hygiene education Right to education behaviours in Afghanistan Reduced risk of violence, abuse or Right to a life without exploitation violence, abuse or explotation Sarah House WASH Consultant on behalf of UNICEF, Afghanistan 1 WASH Components of the Situation Analysis of Children and Women, Afghanistan, 2013 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks to all associated with the WASH sector and outside who gave up their time to participate in the process of development of the WASH components of the Situation Analysis of Children and Women in Afghanistan, 2013. In particular thanks to the family members, school children, teachers, CDC members, Government officials (RRD, MoE, MoPH) and Civil Society Organisations in Bamyan who gave up their time to share experiences and opinions; and to the representatives of civil society organisations, embassies, multilateral and UN agencies who took part in the national stakeholder workshop, provided time for meetings or provided support and information by email. Particular thanks also to the representatives of the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development, Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Urban Development Affairs in Kabul who were involved in planning for the process, organising and co-facilitating the national workshop, participation in various meetings and / or providing support by email; as well as to the representatives of the various UNICEF Sections, the SitAn management team and the UNICEF WASH team who managed and facilitated the process throughout. -

Following Walnut Footprints(Juglans Regial.)

Following Walnut Footprints Footprints Walnut Following Cultivation Culture Number 17 Scripta Horticulturae | Scripta Horticulturae Number 17 History Traditions Following Walnut Footprints (Juglans regia L.) ISBN 978-94-6261-003-3 Cultivation and Culture, Folklore and History, Traditions and Uses 9 789462 610033 Uses A Publication of the International Society ISSN 1813-9205 for Horticultural Science ISBN 978-94-6261-003-3, Scripta Horticulturae Number 17 and the International Nut & Dried Fruit Council Following Walnut Footprints in Afghanistan R. Knowles Horticulture and Forestry Consultant, 56 Lincroft, Cranfield, Beds, UK. MK43 0HT Country Introduction Afghanistan is landlocked and shares borders with Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and China. With a population of around 30 million, it has an area of 647,500 km2, making it slightly larger than France. Only 12% of the land area is cultivated and only 8% is irrigated. Current forest coverage is estimated at about 2.2 million hectares (3.4% of Afghanistan’s territory). The country is divided into 34 provinces and although supposedly administered from the capital, Kabul, the reach of government to rural areas is weak. Approximately 10% of the population live in Kabul. There are many ethnic and religious divisions compounded by tribal allegiances. Pashtuns (42%) and Tajiks (27%) are in the majority, followed by Hazaras and Uzbeks (9% each) and several smaller minorities. Sunnis form the religious majority (80-85%), but there are substantial numbers of Shiites (15-19%) especially among the Hazaras. Ismaili Muslims are common in certain areas. Chapter The climate can be extreme with winter temperatures averaging -15°C in parts of Badakhshan and Nuristan in the North East. -

AFGHANISTAN Northeast

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (7 October – 13 October 2019) KEY FIGURES IDPS IN 2019 (AS OF 13 OCT) 314,200 People displaced by conflict 239,800 Received assistance NATURAL DISASTER IN 2019 (AS OF 13 OCT) 295,700 Number of people affected by natural disasters Conflict incident RETURNEES IN 2019 (AS OF 05 OCT) 373,700 Internal displacement Returnees from Iran Disruption of services 21,120 Returnees from Pakistan 16,730 Returnees/deportees from other countries Northeast: Over 10,000 people displaced HRP REQUIREMENTS & FUNDING Armed clashes continued between Afghanistan National Security Forces (ANSF) and an Non-State Armed Group (NSAG) in the Khustak area of Jorm 612M district in Badakhshan province, as well as Khowja Ghar, Darqad and Khowja Requested (US$) Bahawuddin districts in Takhar province. Last week, clashes between ANSF M and an NSAG resulted in the displacement of around 10,500 people from 393 Yangi Qala and Darqad to Taloqan city. Some displaced families moved to 64% funded (US$) inaccessible remote villages in Darqad and Khowja Bahawuddin district in AFGHANISTAN HUMANITARIAN Takhar province. FUND (AHF) Inter-agency teams assessed 19,705 internally displaced persons (IDPs) as being in need of humanitarian assistance in Takhar, Badakhshan, Baghlan 30.64M and Kunduz. During the reporting period, 23,527 IDPs who were affected by Contributions (US$) conflict were reached with food, relief items, and hygiene kits in Takhar, 5.07M Badakhshan, Baghlan and Kunduz provinces. Pledges (US$) North: Over 29,000 people received humanitarian 25.82M Expenditure (US$) assistance 1.65M Clashes between an NSAG and the ANSF in Balkh, Jawzjan and Faryab Available for allocation (US$) provinces continued in the reporting period while humanitarian access in most northern districts remained restricted. -

Afghan Taliban Intent

3rd Edition Jan 11 1 Purpose To ensure that U.S. Army personnel have a relevant, comprehensive guide to help enhance cultural understanding; to use in capacity building and counterinsurgency operations while deployed in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. 2 About This Book The Smart Book contains information designed to enhance Soldier’s knowledge of Afghanistan, including history, politics, country data and statistics, and the military operational environment. The Smart Book concludes with an overview of the culture of Afghanistan including religion, identity, behavior, communication and negotiation techniques, an overview of ethnic groups, a regional breakdown outlining each province, a language guide, and cultural proverbs, expressions and superstitions. 3 Focus “We must demonstrate to the people and to the Taliban that Afghan, US and coalition forces are here to safeguard the Afghan people, and that we are in this to win.” - General David H. Petraeus Commander, ISAF “Change of Command” 5 July 2010 The Washington Post 4 Table of Contents Topic Page History 9 Political 20 Flag of Afghanistan 21 Political Map 23 Afghan Provinces and Districts 24 Political Structure 25 President of Afghanistan and Cabinet 26 Provincial Governors 28 Country Data 30 Location and Bordering Countries 31 Comparative Area 32 Social Statistics 33 Economy Overview 34 History of Education 39 5 Table of Contents Topic Page Military Operational Environment 40 Terrain and Major Lines of Communication by ISAF RC 41 International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Missions -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation December 2017 SuppORt IS OuR mISSIOn European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security situation December 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9494-837-3 doi: 10.2847/574136 © European Asylum Support Office 2017 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © DVIDSHUB (Flickr) Afghan Convoy Attacked Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT AFGHANISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the following national asylum and migration departments as the co-authors of this report: Belgium, Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Cedoca (Center for Documentation and Research) France, Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless persons (OFPRA), Information, Documentation and Research Division Poland, Country of -

Mines and Mineral Occurrences of Afghanistan

Mines and Mineral Occurrences of Afghanistan Compiled by G.J. Orris1 and J.D. Bliss1 Open-File Report 02-110 2002 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1USGS, Tucson, Arizona TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………..……... 3 DATA SOURCES, PROCESSING, AND ACCURACY ………………... 3 DATA ………………………………………………………………………….... 5 REFERENCES ………..………………………………………………………....8 APPENDIX A: Afghanistan Mines and Mineral Occurrences.. 11 TABLES Table 1. Provinces of Afghanistan .......................................................... 7 Table 2. Commodity Codes ..................................................................... 8 2 INTRODUCTION This inventory of more than 1000 mines and mineral occurrences in Afghanistan was compiled from published literature and the files of project members of the National Industrial Minerals project of the U.S. Geological Survey. The compiled data have been edited for consistency and most duplicates have been deleted. The data cover metals, industrial minerals, coal, and peat. Listings in the table represent several levels of information, including mines, mineral showings, deposits, and pegmatite fields. DATA SOURCES, PROCESSING, AND ACCURACY Data on more than 1000 Afghanistan deposits, mines, and occurrences were compiled from published literature and digital files of the project members of the National Industrial Minerals project of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The data include information on metals, nonmetals, construction materials, coal, and peat. Three previous compilations of Afghanistan mineral resources were the dominant sources used for this effort. In 1995, the United Nation's Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific published a summary of the geology and mineral resources of Afghanistan as part of their Atlas of Mineral Resources series. -

In Nuristan: Disfranchisement and Lack of Data

The 2018 Election Observed (4) in Nuristan: Disfranchisement and lack of data Author : Obaid Ali Published: 17 November 2018 Downloaded: 16 November 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-admin/post.php Organising elections in Nuristan, one of the most remote, under-served and unknown provinces, presents a severe challenge. Most villages are far from their nearest district centre and all of the districts are under some degree of Taleban control or influence. In two districts – Mandol and Du-Ab – people were fully deprived of their right to vote. Elections were held in the six others, but even then only in parts of the districts. Contradictions on the number of polling centres reported as having been opened on election day have also raised suspicions that some vote rigging may have taken place. AAN’s Obaid Ali, Jelena Bjelica and Thomas Ruttig scrutinise the context in Nuristan which makes holding free, fair and inclusive elections so very difficult and report on what was a troubling election day where few Nuristanis were able to exercise their franchise. Holding elections in Nuristan in 2018 was difficult. Mountainous terrain plus insurgency made logistics, eg getting voting material in and out, tricky. It was then difficult or impossible for many people to get to polling centres, if they had managed to register and if the centres opened. Monitoring the poll was even more difficult. It seems that, in many places, the IEC ‘subcontracted’ security and administration of the elections to local elders. Meanwhile, discrepancies in some of the basic reporting about election day, for example how many polling centres actually opened, flag up concerns about vote-rigging. -

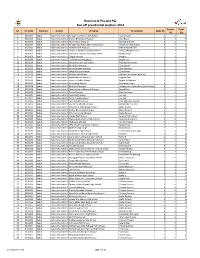

Final List of Pcs and Pss Run-Off Presidential Election, 2014

Final List of PCs and PSs Run-off presidential election, 2014 Female Total No PC Code Province District PC Name PC locatioin Male PS PS PSs 1 0101001 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan High School Asakzai lane 3 3 6 2 0101002 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mullah Mahmood Mosque Shur Bazar 3 3 6 3 0101003 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Akhir-e-Jada Mosque Maiwand Street 2 2 4 4 0101004 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan Secondary School Se Dokan Chandawaul 3 3 6 5 0101005 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Pakhtaferoshi Mosque Pakhta forushi lane 2 3 5 6 0101006 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Daqeqi-e-Balkhi Secondary School Saraji, Ahangari Lane 3 3 6 7 0101007 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mastoora-e-Ghoori Seconday School Babay Khudi 3 3 6 8 0101008 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Eidgah Mosque Abdgah 3 3 6 9 0101009 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Fatiha-Khana-e-Baghqazi Baghe Qazi 2 2 4 10 0101010 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Aisha-e-Durani High School Pule baghe Umumi 3 2 5 11 0101011 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Bibi Sidiqa Mosque Chendawul 2 1 3 12 0101012 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Sar-e-Gardana Mosque Sare Gardana 1 1 2 13 0101013 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Takya-Khana-e-Omomi Chendawul 3 2 5 14 0101014 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Khawja Safa Mosqe Asheqan wa Arefan Bala Joy 1 1 2 15 0101015 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Baghbankocha Mosque Baghbanlane 2 1 3 16 0101016 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Onsuri-e-Balkhi School Baghe Ali Mardan 3 2 5 17 0101017 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Imam Baqir Mosqe Hazaraha village 2 1 3 18 0101018 Kabul