Country of Origin Report on Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan

Nxxx,2009-09-05,A,009,Bs-BW,E3 THE NEW YORK TIMES INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2009 ØØN A9 NATO Airstrike Magnifies Political Divide Over the War in Afghanistan governor of Ali Abad, Hajji Habi- From Page A1 bullah, said the area was con- with the Afghan people.” trolled by Taliban commanders. Two 14-year-old boys and one The Kunduz area was once 10-year-old boy were admitted to calm, but much of it has recently the regional hospital here in Kun- slipped under the control of in- duz, along with a 16-year-old who surgents at a time when the Oba- later died. Mahboubullah Sayedi, ma administration has sent thou- a spokesman for the Kunduz pro- sands of more troops to other vincial governor, said most of the parts of the country to combat an estimated 90 dead were militants, insurgency that continues to gain judging by the number of charred strength in many areas. pieces of Kalashnikov rifles The region is patrolled mainly found. But he said civilians were by NATO’s 4,000-member Ger- also killed. man force, which is barred by In explaining the civilian German leaders from operating deaths, military officials specu- in combat zones farther south. lated that local people were con- The United States has 68,000 scripted by the Taliban to unload troops in Afghanistan, more than the fuel from the tankers, which any other nation; other countries were stuck near a river several fighting under the NATO com- miles from the nearest villages. mand have a combined total of about 40,000 troops here. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Environment Scan: 01-15 Dec 2017 China

ENVIRONMENT SCAN: 01-15 DEC 2017 CHINA (Geo-Strat, Geo-Politics & Geo Economics) Brig Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd) World Political Parties Dialogue Concludes with ‘Beijing Initiative’. One of the biggest meetings of global political parties wrapped-up in Beijing on 3 December 2017. It was the first major multilateral diplomacy event hosted by China after the recently concluded 19th CPC National Congress. It was also the first time the CPC held a high-level meeting with such a wide range of political parties from around the world. Over 600 delegates representing nearly 300 political parties and political organizations from over 120 countries attended the meeting.The meeting was officially reported to be a complete success with a broad consensus reached. Year end - China Focus: From Follower to Leader: China Emerges at High-Tech Frontier. After years of focusing on innovation, China has caught up fast. Silicon Valley has long been considered the most viable option for starting a business in the tech sector. Now, this is beginning to change. Known as "sea turtles," a growing number of overseas-educated Chinese are returning to their home country, turning down opportunities in Silicon Valley to make a splash in China's emerging tech sector. As the number of Chinese students at overseas universities surged to 544,500 in 2016, the number of sea turtles also surged, with 432,500 returning to China last year, nearly 60 percent more than 2012, according to the Ministry of Education. The reverse brain drain has benefited China's tech companies. A brilliant example is Royole, a company founded in 2012 by "sea turtle" Liu Zihong, a Stanford graduate. -

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021)

AFGHANISTAN Weekly Humanitarian Update (12 – 18 July 2021) KEY FIGURES IDPs IN 2021 (AS OF 18 JULY) 294,703 People displaced by conflict (verified) 152,387 Received assistance (including 2020 caseload) NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2021 (AS OF 11 JULY) 24,073 Number of people affected by natural disasters Conflict incident RETURNEES IN 2021 Internal displacement (AS OF 18 JULY) 621,856 Disruption of services Returnees from Iran 7,251 Returnees from Pakistan 45 South: Fighting continues including near border Returnees from other Kandahar and Hilmand province witnessed a significant spike in conflict during countries the reporting period. A Non-State Armed Group (NSAG) reportedly continued to HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE apply pressure on District Administrative Centres (DACs) and provincial capitals PLAN (HRP) REQUIREMENTS & to expand areas under their control while Afghan National Security Forces FUNDING (ANSF) conducted clearing operations supported by airstrikes. Ongoing conflict reportedly led to the displacement of civilians with increased fighting resulting in 1.28B civilian casualties in Dand and Zheray districts in Kandahar province and Requirements (US$) – HRP Lashkargah city in Hilmand province. 2021 The intermittent closure of roads to/from districts and provinces, particularly in 479.3M Hilmand and Kandahar provinces, hindered civilian movements and 37% funded (US$) in 2021 transportation of food items and humanitarian/medical supplies. Intermittent AFGHANISTAN HUMANITARIAN outages of mobile service continued. On 14 July, an NSAG reportedly took FUND (AHF) 2021 control of posts and bases around the Spin Boldak DAC and Wesh crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Closure of the border could affect trade and 43.61M have adverse implications on local communities and the region. -

Afghanistan: the Situation of Christian Converts

+*-/ !"#)$./) # .$/0/$*)*!#-$./$)*)1 -/. 7 April 2021 © Landinfo 2021 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33 A P.O. Box 2098 Vika NO-0125 Oslo Tel.: (+47) 23 30 94 70 Ema il: [email protected] www.landinfo.no *0/ )$)!*ҁ. - +*-/. The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information (COI) to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The informa tion is collected a nd analysed in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of Origin Information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. -

“TELLING the STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: a Regional Perspective (2011-2016)

“TELLING THE STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective (2011-2016) Emma Hooper (ed.) This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. © 2016 CIDOB This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel.: 933 026 495 www.cidob.org [email protected] D.L.: B 17561 - 2016 Barcelona, September 2016 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES 5 FOREWORD 11 Tine Mørch Smith INTRODUCTION 13 Emma Hooper CHAPTER ONE: MAPPING THE SOURCES OF TENSION WITH REGIONAL DIMENSIONS 17 Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective .......... 19 Zahid Hussain Mapping the Sources of Tension and the Interests of Regional Powers in Afghanistan and Pakistan ............................................................................................. 35 Emma Hooper & Juan Garrigues CHAPTER TWO: KEY PHENOMENA: THE TALIBAN, REFUGEES , & THE BRAIN DRAIN, GOVERNANCE 57 THE TALIBAN Preamble: Third Party Roles and Insurgencies in South Asia ............................... 61 Moeed Yusuf The Pakistan Taliban Movement: An Appraisal ......................................................... 65 Michael Semple The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan ....................................................................... -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’S Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

JANUARY 2011 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’s Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Author Geert Gompelman (MSc.) is a graduate in Development Studies from the Centre for International Development Issues Nijmegen (CIDIN) at Radboud University Nijmegen (Netherlands). He has worked as a development practitioner and research consultant in Afghanistan since 2007. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank his research colleagues Ahmad Hakeem (“Shajay”) and Kanishka Haya for their assistance and insights as well as companionship in the field. Gratitude is also due to Antonio Giustozzi, Arne Strand, Petter Bauck, and Hans Dieset for their substantive comments and suggestions on a draft version. The author is indebted to Mervyn Patterson for his significant contribution to the historical and background sections. Thanks go to Joyce Maxwell for her editorial guidance and for helping to clarify unclear passages and to Bridget Snow for her efficient and patient work on the production of the final document. -

U.S. Military Engagement in the Broader Middle East

U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY WWW.WASHINGTONINSTITUTE.ORG The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. Policy Focus 143, April 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing fromthe publisher. ©2016 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1111 19th Street NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: An F-16 from the Egyptian Air Force prepares to make contact with a KC-135 from the 336th ARS during in-flight refueling training. (USAF photo by Staff Sgt. Amy Abbott) Contents Acknowledgments V I. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF U.S. MILITARY OPERATIONS 1 James F. Jeffrey 1. Introduction to Part I 3 2. Basic Principles 5 3. U.S. Strategy in the Middle East 8 4. U.S. Military Engagement 19 5. Conclusion 37 Notes, Part I 39 II. RETHINKING U.S. MILITARY STRATEGY 47 Michael Eisenstadt 6. Introduction to Part II 49 7. American Sisyphus: Impact of the Middle Eastern Operational Environment 52 8. Disjointed Strategy: Aligning Ways, Means, and Ends 58 9. -

Special Report on Kunduz Province

AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE © 2015/Xinhua United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT SPECIAL REPORT ON KUNDUZ PROVINCE United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan December 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2015/ Jawed Omid/Xinhua. A man searches for the bodies of his relatives inside the ruins of the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz city. (On 3 October, a United States AC-130 aircraft carried out a series of airstrikes against the hospital, resulting in at least 30 deaths and 37 injured). Photo taken on 11 October 2015. "Citizens of Kunduz were subjected to a horrifying ordeal. The street by street fighting coupled with a breakdown of the rule of law created an environment where civilians were subjected to shooting, other forms of violence, abductions, denial of medical care and restrictions of movement out of the city.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, Kabul, 25 October 2015. “This event was utterly tragic, inexcusable, and possibly even criminal. International and Afghan military planners have an obligation to respect and protect civilians at all times, and medical facilities and personnel are the object of a special protection. These obligations apply no matter whose air force is involved, and irrespective of the location." United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, Geneva, 3 October 2015, public statement about attack against the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital. -

Balkh's Chamtal District Cleaned up from Rebels

www.outlookafghanistan.net www.thedailyafghanistan.com facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan facebook.com/The.Daily.Afghanistan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Add: Sarai Ghazni, District 3, Kabul Add: Sarai Ghazni, District 3, Kabul Back Page August 22, 2017 Jalalabad Clear Ghazni Kandahar Clear Clear Mazar Clear Herat Clear Bamayan Clear Kabul Clear Daily Outlook 36°C 32°C 38°C 37°C 33°C 26°C 31°C Weather 28°C 16°C 24°C 25°C 16°C 12°C 18°C Forcast Balkh’s Chamtal District Cleaned up from Rebels MAZAR-I-SHARIF - Local officials on Monday said Chamtal district of Security Forces northern Balkh province has been cleaned of militants during an Af- Recapture Some Areas ghan forces operation. An operation launched by the Shahin of Mirzawlang Military Corps against militants was SAR-I-PUL CITY - Security forces have underway since Saturday night and taken control of Sheram and Kalta Taw ar- was ended late on Sunday. eas of Mirzawlang village in northern Sar- Amanullah Mobin, the commander i-Pul province, an official said on Monday. for the corps, told reporters that Governor Mohammad Zahir Wahdat told around 50 militants suffered casual- Pajhwok Afghan News the security forces ties and eight others were arrested carried out a predawn operation for retak- during the operation. Six security ing the valley. The security personnel suf- personnel were also killed. fered no casualties. He said that there were no rebels cur- Mirzawlang was overrun by militants on rently in Chamtal district after the August 4 when 50 civilians were reported- operation. -

Daily Situation Report 31 October 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

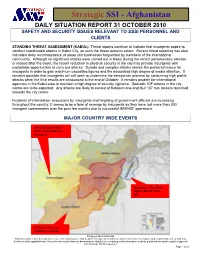

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 31 OCTOBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced at the end of October. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past few months due to successful IM/ANSF operations. MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Herat: Influencial local Tribal Leader killed by insurgents Nangarhar: Five attacks against Border Police OPs Helmand: Five local residents murdered Privileged and Confidential This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. -

Report 2013–1124

Prepared in cooperation with the Afghan Geological Survey under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photo showing mountainous terrain and the alluvial floodplain of a small tributary in the upper reaches of the Kabul River Basin located northeast of Kabul Afghanistan, 2004 (Photograph by Peter G. Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey). Topographic and Hydrographic GIS Datasets for the Afghan Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey 2013 Mineral Areas of Interest By Brittany N. Casey and Peter G. Chirico Open-File Report 2013–1124 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report.