The Motivations and Form of Nietzsche's Classicism 1869-1872 (Under the Direction of Eric Downing)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A+ Grade Project

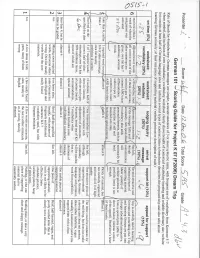

og(s^-l -0 N l-trr ? 6 a: 5F / q\ P P € x o F-.;3 "Afi o \ B:-: * + o o-o.6:l : ac= E =i,;, 5 ;34: 2: 93: u | { eP.99a 5 g -?a6333:;:.3-r \ a=t 1? i^+ 9of;A 3: -: i c f ;- P -= = ? 4Bio o : 99:9 !r \J+'e : 5.. - 1:-=.92 A !.. - 6 0 0 =Y (n *9 'r F* !- 3S1* 9l : a 9-i =: la=.938s.yI i i " -?: I -; +d; i =? -e s'c'H< ^i 9 =i6!18 i:9-4i q'k 63= {[s a;;i tE1r CI' = = o ; a: i i d'isEai'; €FfrE f r 5- \an ;?!>RSO = = dE < F . > *i:3-:1F 6;g39:-;i: e-a 2 ggHei i i a E r. < =! - o o 6E3: € E -: a;.i: +igBE-Hi:i its3; =id-_?c1 : i q a3 € As ^=. Fa1i:* B6 o q'.3 Ir ld P = -1aP 6 = 1l*ae3*: 'qF4'+=€ =az= a a jo .9; IN ;eB Ei4EiZF :9l"J" P! =; E icF=;l c e*;r,! < ed.B. t j- =:; F 1\ :=- 6 A.-\ g N --l Z ;3?=.6Br 6 a =a 9 id -ii ^l x 'A;i55s-:;- 9dii o 2 ; =9F :6 i -o-f o !r -=$3' { U) : -*' \o a-6' 6-. j-:;5 N o g 3P.Z ! F-i:9 * 92I d Ee96 (t) ig,t= 3iAAliF aoi a P \gEFtr€FT q s aqi 5&==;:;' ?6ek I g #: q i E I 7+2'a :.E 6-=_*P o dQ :;g:'! L + &oi o (/\ :," ia _;6= f x i 5 5aE;ie E ; a93.3i 6' E!9 3*iin' t I 9-3 -Ft q 60q; tt o) gL :q3F1g aJ 5"a: (D 994 3! 3 fia;; '!) F?3gfi;:;. -

WBFSH Eventing Breeder 2020 (Final).Xlsx

LONGINES WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS OF EVENTING HORSES (includes validated FEI results from 01/10/2019 to 30/09/2020 WBFSH member studbook validated horses) RANK BREEDER POINTS HORSE (CURRENT NAME / BIRTH NAME) FEI ID BIRTH GENDER STUDBOOK SIRE DAM SIRE 1 J.M SCHURINK, WIJHE (NED) 172 SCUDERIA 1918 DON QUIDAM / DON QUIDAM 105EI33 2008 GELDING KWPN QUIDAM AMETHIST 2 W.H. VAN HOOF, NETERSEL (NED) 142 HERBY / HERBY 106LI67 2012 GELDING KWPN VDL ZIROCCO BLUE OLYMPIC FERRO 3 BUTT FRIEDRICH 134 FRH BUTTS AVEDON / FRH BUTTS AVEDON GER45658 2003 GELDING HANN HERALDIK XX KRONENKRANICH XX 4 PATRICK J KEARNS 131 HORSEWARE WOODCOURT GARRISON / WOODCOURT GARRISON104TB94 2009 MALE ISH GARRISON ROYAL FURISTO 5 ZG MEYER-KULENKAMPFF 129 FISCHERCHIPMUNK FRH / CHIPMUNK FRH 104LS84 2008 GELDING HANN CONTENDRO I HERALDIK XX 6 CAROLYN LANIGAN O'KEEFE 128 IMPERIAL SKY / IMPERIAL SKY 103SD39 2006 MALE ISH PUISSANCE HOROS 7 MME SOPHIE PELISSIER COUTUREAU, GONNEVILLE SUR127 MER TRITON(FRA) FONTAINE / TRITON FONTAINE 104LX44 2007 GELDING SF GENTLEMAN IV NIGHTKO 8 DR.V NATACHA GIMENEZ,M. SEBASTIEN MONTEIL, CRETEIL124 (FRA)TZINGA D'AUZAY / TZINGA D'AUZAY 104CS60 2007 MARE SF NOUMA D'AUZAY MASQUERADER 9 S.C.E.A. DE BELIARD 92410 VILLE D AVRAY (FRA) 122 BIRMANE / BIRMANE 105TP50 2011 MARE SF VARGAS DE STE HERMELLE DIAMANT DE SEMILLY 10 BEZOUW VAN A M.C.M. 116 Z / ALBANO Z 104FF03 2008 GELDING ZANG ASCA BABOUCHE VH GEHUCHT Z 11 A. RIJPMA, LIEVEREN (NED) 112 HAPPY BOY / HAPPY BOY 106CI15 2012 GELDING KWPN INDOCTRO ODERMUS R 12 KERSTIN DREVET 111 TOLEDO DE KERSER -

Ausschreibung

AUSSCHREIBUNG Neuverpachtung Burggaststätte Rudelsburg mit Außensitzplätzen Im Rahmen der Altersnachfolge wird zum nächstmöglichen Zeitpunkt ein neuer Pächter für die Burggaststätte Rudelsburg in Saaleck bei Naumburg (Saale) gesucht. Die Gaststätte ist seit über 30 Jahren ununterbrochen in Betrieb und ein attraktives Ausflugsziel inmitten des Weinanbaugebiets Saale-Unstrut auf der Straße der Romanik. Die Region im Süden Sachsen-Anhalts befindet sich im Zentrum des Städtedreiecks Leipzig – Erfurt – Gera und strebt derzeit die Anerkennung als Welterbe an. Die Rudelsburg ist zu Pfingsten jährlicher Tagungsort des Verbandes Alter Corpsstudenten e.V. (VAC) sowie Standort des jährlichen Treffens der Kösener Senioren-Convents-Verband (KSCV), dem Dachverband der ältesten Studentenverbindungen Deutschlands. Im Rahmen des Pächterwechsels soll eine Schließung der Gaststätte vermieden werden. 1. Allgemeines 1.1. Saaleck Saaleck ist ein Ortsteil der Stadt Naumburg (Saale) und liegt am Ufer der Saale inmitten der Weinregion Saale-Unstrut. Der Ort ist in ca. 30 Minuten jeweils von der A 9 über die B87 bzw. von der A 4 über die B88 aus zu erreichen. Die nächste Bahnstation befindet sich in Bad Kösen. Ein ICE-Anschluss besteht am Hauptbahnhof Naumburg (Saale). 1.2. Lage des Objekts Die Rudelsburg liegt als Höhenburg am Südufer der Saale auf einem Bergrücken ungefähr 85 Meter über dem Fluss oberhalb von Saaleck. Sie ist für Kraftfahrzeuge einschließlich Busse über eine Straße, für Fußgänger über Wanderwege erreichbar. Am Saaleufer unterhalb der Burg befindet sich ein Schiffsanleger der Saaleschifffahrt Bad Kösen. 1.3. Gebäude Die Rudelsburg ist einer der touristischen Schwerpunkte für Tages- und Übernachtungsgäste der Region. Verpachtet wird die gesamte Rudelsburg. Alle Räume der Rudelsburg, mit Ausnahme des Trauzimmers, sind der gastronomischen Nutzung zugeordnet. -

Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School April 2021 Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis William A. B. Parkhurst University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Parkhurst, William A. B., "Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis by William A. B. Parkhurst A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Lee Braver, Ph.D. Vanessa Lemm, Ph.D. Alex Levine, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 16th, 2021 Keywords: Fredrich Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, History of Philosophy, Continental Philosophy Copyright © 2021, William A. B. Parkhurst Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my mother, Carol Hyatt Parkhurst (RIP), who always believed in my education even when I did not. I am also deeply grateful for the support of my father, Peter Parkhurst, whose support in varying avenues of life was unwavering. I am also deeply grateful to April Dawn Smith. It was only with her help wandering around library basements that I first found genetic forms of diplomatic transcription. -

Heartland of German History

Travel DesTinaTion saxony-anhalT HEARTLAND OF GERMAN HISTORY The sky paThs MAGICAL MOMENTS OF THE MILLENNIA UNESCo WORLD HERITAGE AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu 6 good reasons to visit Saxony-Anhalt! for fans of Romanesque art and Romance for treasure hunters naumburg Cathedral The nebra sky Disk for lateral thinkers for strollers luther sites in lutherstadt Wittenberg Garden kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz for knights of the pedal for lovers of fresh air elbe Cycle route Bode Gorge in the harz mountains The Luisium park in www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu the Garden Kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz Heartland of German History 1 contents Saxony-Anhalt concise 6 Fascination Middle Ages: “Romanesque Road” The Nabra Original venues of medieval life Sky Disk 31 A romantic journey with the Harz 7 Pomp and Myth narrow-gauge railway is a must for everyone. Showpieces of the Romanesque Road 10 “Mona Lisa” of Saxony-Anhalt walks “Sky Path” INForMaTive Saxony-Anhalt’s contribution to the history of innovation of mankind holiday destination saxony- anhalt. Find out what’s on 14 Treasures of garden art offer here. On the way to paradise - Garden Dreams Saxony-Anhalt Of course, these aren’t the only interesting towns and destinations in Saxony-Anhalt! It’s worth taking a look 18 Baroque music is Central German at www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu. 8 800 years of music history is worth lending an ear to We would be happy to help you with any questions or requests regarding Until the discovery of planning your trip. Just call, fax or the Nebra Sky Disk in 22 On the road in the land of Luther send an e-mail and we will be ready to the south of Saxony- provide any assistance you need. -

What Was the Cause of Nietzsche's Dementia?

PATIENTS What was the cause of Nietzsche’s dementia? Leonard Sax Summary: Many scholars have argued that Nietzsche’s dementia was caused by syphilis. A careful review of the evidence suggests that this consensus is probably incorrect. The syphilis hypothesis is not compatible with most of the evidence available. Other hypotheses – such as slowly growing right-sided retro-orbital meningioma – provide a more plausible fit to the evidence. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) ranks among the paintings had to be removed from his room so that most influential of modern philosophers. Novelist it would look more like a temple2. Thomas Mann, playwright George Bernard Shaw, On 3 January 1889, Nietzsche was accosted by journalist H L Mencken, and philosophers Martin two Turinese policemen after making some sort of Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Jacques Derrida, and public disturbance: precisely what happened is not Francis Fukuyama – to name only a few – all known. (The often-repeated fable – that Nietzsche acknowledged Nietzsche as a major inspiration saw a horse being whipped at the other end of the for their work. Scholars today generally recognize Piazza Carlo Alberto, ran to the horse, threw his Nietzsche as: arms around the horse’s neck, and collapsed to the ground – has been shown to be apocryphal by the pivotal philosopher in the transition to post-modernism. Verrecchia3.) Fino persuaded the policemen to There have been few intellectual or artistic movements that have 1 release Nietzsche into his custody. not laid a claim of some kind to him. Nietzsche meanwhile had begun to write brief, Nietzsche succumbed to dementia in January bizarre letters. -

Nietzsche's Collapse: the View from Paraguay

Nietzsche's collapse: The view from Paraguay The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Guthke, Karl S. 1997. Nietzsche's collapse: The view from Paraguay. Harvard Library Bulletin 7 (3), Fall 1996: 25-36. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42665563 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Nietzsche's Collapse: The View from Paraguay Karl S. Guthke scar Wilde in chains on the platform of Paddington Station, Rimbaud 0 smuggling firearms in Abyssinia while Paris is in ecstasy about his Illuminations, Nietzsche, tears streaming down his cheeks, embracing a fiacre horse in downtown Turin as insanity descends upon him-these scandalous inci- dents, tailor-made for the boulevard press though they are, also sound an alarm in the wider landscape of the cultural history of the time. They stir the fin-de- siecle mind out of its complacency with familiar patterns of thought, and soon enough they become the focal points of a popular mythology that has lasted to this day. In the German-speaking countries, this is of course especially true of Nietzsche's collapse in the first days of January 1889. Gottfried Benn, in his poem "Turin," does not even need to refer to the famous case by name: "Ich laufe auf zerrissenen Sohlen", KARL S. -

Nietzsche's Library

NIETZSCHE’S LIBRARY Compiled by Rainer J. Hanshe A NOTE ON THIS DOCUMENT: The phrase “NIETZSCHE’S ‘LIBRARY’” must be taken liberally, if not expansively. This is an extensive document that traces not only the books which Nietzsche read throughout his life, but also lectures he attended as well as professorial work he was engaged in, the music he listened to and composed, and, finally, denotes when and where he wrote his philosophical works. Its primary concern though is with the books Nietzsche was reading; the most abundant references are to those books. As far as the books which Nietzsche read are concerned, there are lists of these books, but they are strictly alphabetical and therefore not of much value. “NIETZSCHE’S ‘LIBRARY’” traces his reading chronologically, month by month when possible, in order to help map out the intersection between his reading and his writing. To know exactly when Nietzsche was reading what is more beneficial for gaining a deeper understanding of his relationship to other thinkers, writers, poets, etc. Whether or not there is always a direct correlation is to be discerned by each and every reader and researcher, but this document was created in order to facilitate work of this kind. For others, this may be a strict amusement or curiosity, but it does not seem that any such document exists; perhaps it will be helpful. This statement must be qualified though, for some time after I began working on this, someone alerted me to the work of Thomas Brobjer, who has conducted the most significant and important research on Nietzsche’s reading, born of direct contact with the actual books Nietzsche owned. -

Nietzsche in the Magisterial Tradition of German Classical Philology

NIETZSCHE IN THE MAGISTERIAL TRADITION OF GERMAN CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY BY JAMES WHITMAN* Nietzsche spent ten years as an advanced student of classical philology and was a prodigious success; he spent the next ten years as a professor of classical philology and was a prodigious failure. Even casual readers of Nietzsche know the story of his meteoric early career in the dramatic terms in which it is usually told: how Nietzsche was called to the Uni- versity of Basel in 1869, at the sensationally young age of twenty-four, and how he scandalized his colleagues in the discipline within three years by publishing the wild and unscholarly Birth of Tragedy, soon thereafter to abandon classical philology altogether and to be cast into disgrace, continuing to hold his professorship in name only. Few Nietzsche scholars have resisted the temptation to exaggerate the drama of these events. The young Nietzsche, as we most often read about him, was a genius whom simple scholarship could not adequately nourish, a visionary who rapidly shook himself free of the grip of ped- antry.' Such is the standard account of Nietzsche's career, and it is badly distorted. For Nietzsche scholars have contented themselves with a care- less caricature of the history of German classical philology. Certainly there was pedantry among Nietzsche's colleagues, but there was also a tradition that could appeal to Nietzsche's most visionary and self-pro- clamatory tendencies, a magisterial tradition that had arisen in the dec- ades between 1790 and 1820 and flourished in the 1830s and 1840s. It is my purpose in this article to show that Nietzsche identified himself * I would like to thank Professors Anthony Grafton, Samuel Jaffe, Arnaldo Momig- liano, Donald R. -

Klassizismus in Aktion. Goethes 'Propyläen' Und Das Weimarer

Literaturgeschichte in Studien und Quellen Band 24 Herausgegeben von Klaus Amann Hubert Lengauer und Karl Wagner Daniel Ehrmann · Norbert Christian Wolf (Hg.) Klassizismus in Aktion Goethes Propyläen und das Weimarer Kunstprogramm 2016 Böhlau Verlag Wien · Köln · Weimar Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : PUB 326-G26 © 2016 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Umschlagabbildung: Philipp Otto Runge, »Achill und Skamandros« Zeichnung, 1801; © bpk/Hamburger Kunsthalle/Christoph Irrgang Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Korrektorat : Ernst Grabovszki, Wien Umschlaggestaltung : Michael Haderer, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung : Finidr, Cesky Tesin Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-20089-5 Inhaltsverzeichnis EINLEITUNG Daniel Ehrmann · Norbert Christian Wolf Klassizismus in Aktion. Zum spannungsreichen Kunstprogramm der Propyläen .................................. 11 KULTUR UND AUTONOMIE Sabine Schneider »Ein Unendliches in Bewegung«. Positionierungen der Kunst in der Kultur .................................. 47 Hans-Jürgen Schings Laokoon und La Mort de Marat oder Weimarische Kunstfreunde und Französische Revolution ........................... 67 Daniel Ehrmann Bildverlust oder Die Fallstricke der Operativität. Autonomie und Kulturalität der Kunst -

Nietzsche on Time and History

Nietzsche on Time and History authors copy with permission by WdG 2008 ≥ authors copy with permission by WdG 2008 Nietzsche on Time and History Edited by Manuel Dries authors copy with permission by WdG 2008 Walter de Gruyter · Berlin · New York authors copy with permission by WdG 2008 Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper which falls within the guidelines of the ANSI to ensure permanence and durability. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-019009-0 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Ą Copyright 2008 by Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, 10785 Berlin, Germany. All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permis- sion in writing from the publisher. Printed in Germany Cover design: Martin Zech, Bremen. Printing and binding: Hubert & Co GmbH & Co KG, Göttingen. If there is no goal in the whole of history of man’s lot, then we must put one in: assuming, on the one hand, that we have need of a goal, and on the other that we’ve come to see through the illusion of an immanent goal and purpose. And the reason we have need of goals is that we have need of a will—which is the spine of us. -

The German Concept of “Bildung” Then and Now*)

1 Jürgen Oelkers *) The German Concept of “Bildung” then and now 1. Seclusion and freedom “What about Humboldt?” was a question raised two years ago during a student protest at German universities that was to be seen on many posters during the weeks of protest. There were other posters referring to Humboldt. “What about Humboldt” pointed to the apparent threat to higher education originating from the Bologna process. The word “Bologna” sounded no better to German professors, as it stands for a process of educational efficiency deeply alien to the spirit of liberal humanism. • So: “What about Humboldt?” means “What happened to Bildung?” • The equation seems to be self-evident: no one in Germany needs to explain what Humboldt has to do with “Bildung”. • Being a German, what will my lecture be all about? The German term “Bildung” is not only hard explain, but also nearly untranslatable. “Bildung” has a more extensive range of meanings than “education”, implying the cultivation of a profound intellectual culture, and is often rendered in English as “self-cultivation”. The term originated from the European philosophy of Neo-Platonism in 17th century and referred to what is called the “inward from” of the soul. Humboldt’s concept echoes this tradition even though Humboldt was not a Platonist. But “Bildung” was the key concept of German humanism and was backed by famous philosophers like Herder and Hegel as well as classical writers like Goethe or Schiller. The German “Bildungsroman” - novel of Bildung - shows how “Bildung” should work, i.e. experiencing the world in a free and personal way without formal schooling.