The Delius Society Journal Spring 2014, Number 155

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Sir Mark Elder Leads CSO in Exploration of Literature's Influence

ChicagoPride.com News December 13, 2011 Sir Mark Elder leads CSO in exploration of literature's influence on music By GoPride.com News Staff December 13, 2011 https://chicago.gopride.com/news/article.cfm/articleid/24335776 CST actors also to perform scenes from selected plays, January 5-10, and 12-15 CHICAGO, IL -- British conductor Sir Mark Elder makes his return to Orchestra Hall for a two-week residency that explores the influence of Shakespeare and other works of literature on music and features actors from Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST), under the direction of CST Artistic Director Barbara Gaines, bringing the Bard's words to life. Sir Mark Elder's first subscription week of concerts on January 5-10, is an all-Berlioz program, highlighted by the Queen Mab Scherzo and Romeo at the Tomb from the composer's Romeo and Juliet. Select readings from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, performed by Brendan Marshall-Rashid and Susan Strunk from the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, precede these two works. British violist Lawrence Power also makes his CSO debut on these concerts and is featured in Berlioz's Harold in Italy, a work Paganini encouraged Berlioz to compose and was inspired by Lord Byron's poetry. Elder concludes his two-week winter residency January 12-15, with a further exploration into Shakespeare's influence on music through works by Delius, Elgar, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky. Included on the program is Elgar's rarely performed orchestral work Falstaff, which portrays Shakespeare's Sir John Falstaff from Henry IV. Actor Greg Vinkler brings to life passages from Henry IV Parts 1 and 2. -

The Late Summer Newsletter

AUGUST 2020 Issue No: 17 Welcome to the late summer newsletter. AGM and the musical phrasing stand out, always with clear thought for the meaning. Furthermore, the perfect Please note that the AGM has been postponed to December velvety colouring of their basses, with no forcing of the 2020 – date/venue to follow in the next newsletter. As the Holst th lower register whatsoever, eases the tuning and Birthplace Trust annual concert scheduled for 19 September harmonic construction of the ensemble. Preece proves 2020 has been cancelled, so too must our AGM pencilled in for that Holst is more than The Planets. that afternoon. Hopefully, if concerts resume in the next three months, we could have our AGM in the afternoon of a Saturday Jerónimo Marin before Christmas with a concert in Cheltenham that evening. HOLST/ VAUGHAN WILLIAMS/ WALT WHITMAN SAVITRI Holst, Vaughan Williams and the poetry of Walt Holst’s one-act opera will be performed in the gardens of Whitman Lauderdale House, Highgate, London, with two performances each evening on August 13th, 15th, 20th and 22nd. The The poems of Walt Whitman, and in particular his production given by Hampstead Garden Opera will be staged Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, soon inspired by Julia Mintzer and conducted by Thomas Payne (please visit new generations of English composers. These website at https://hgo.org.uk/savitri/ for further detail). included Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav von Holst. Vaughan Williams was introduced to Whitman’s PART SONGS BY HOLST poetry by Bertrand Russell in 1892, the year of the poet’s death. -

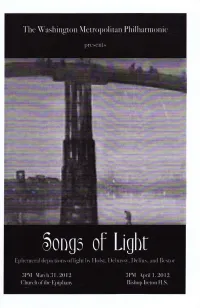

2012-0331 Program.Pdf

I\TI\OI)~I ClIO:-;~ Welcorne to Songs ofLight! JUSllikc the anists oftheir day, musicians ofthe Impressionistic CI"'J were intrigued with the cfTt.'C(S ofligtll and 50"0",11 to portray this in their music. With diminished light. the harsh cfTetts ofindustrialization were muted and these llt."\\ landst<q>cs Wert softened and made bc-Jutiful again. l1lis aftcmoon's program is filled wim ethereal depietions of light by Delius. Dehll"S)', and l-Io1st as well a~ with a sparkling new work by Charles Beslor. lei these airy musical work..<; lIallspon you to a time ofday where healilifulligiu softens the lrOublcs ofthe world bringingoullhe best ofany place. Enjo}! ,. As Illusie is lhe poetry OfSOlilld. so is paiming Ihe poclry ofsight. ~ - JUfIlt'JAblJOIf AfcNetillflllfJtler W:.ashillg'lotl Ml'tropolil.U1 rhilhanllonic. UI~"SSCS James. Music Dirt:('lOf & Condm:lor Ulys.<iCS S. James is a fonner lromhonist who studied in BOSlOll aud at Tauglcwood ..•..ith William Gibson. principal trombonist of the Bostoll Symphony On:heslra. He grddlllHcd in 1958 ....ith honurs in llIusi<: from Brown University. Mtcr a 20 yCM ~'aIttr as a surfoc-c ....~Mfare Naval Officer. followed by a second tareer as an organization and management de...e1opmem consultam. he bn-arne the music dire~1or and priocipal condtl~1or of Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Association in 1985. The Assodation sponsors Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic. Washington ~lctropolitan YOUlh Orchestra. Washington Metropolitan Concen Orchestrd. a weekly summer chamber musie series at The Lyceum ill Old Towll Alexandria. and all anllual cOl1lpo~ition COllllletition for the Mid-Atlantic StUll'S. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 47,1927

« ''WW BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRH INC. FORTY-SEVENTH art . SEASON ^ 1927-1928 PR5GR7W1E BOSTON COMMON, TREMONT STREET AT WEST Open Their New Enlarged Store Three modern buildings DRESSES and nineteen separate and COATS distinct selling floors, for and seventy-one WOMEN, beautiful separate MISSES and slv JUNIORS FUR COATS MILLINERY ACCESSORIES ORIENTAL RUGS SILKS LINENS and UPHOLSTERY It is well worth while to see our beautiful new windows, both on Tremont and West Streets. They serve as a charming setting for all that is new and best in women's wear. They are the latest note in window display and are classed among the finest in the East. SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephones, Ticket and Administration Offices, Back Bay 1492 on ^jmpMomj 'Uirdhestra INC SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor FORTY-SEVENTH SEASON. 1927-1928 MONDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 14, at 8.15 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1927, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President BENTLEY W. WARREN Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer FREDERICK P. CABOT FREDERICK E. LOWELL ERNEST B. DANE ARTHUR LYMAN N. PENROSE HALLOWELL EDWARD M. PICKMAN M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE HENRY B. SAWYER JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W. WARREN W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager 1 STEIN WAY the instrument of the immortals Not only the best piano, but the best piano value It is possible to build a piano to beauty of line and tone, it is the sell at any given price, but it is not greatest piano value ever offered! often possible to build a good . -

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No 298662) President Lionel Carley BA, PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Piers Lane AO, Hon DMus Martin Lee-Browne CBE David Lloyd-Jones BA, FGSM, Hon DMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Anthony Payne Website: delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 THE DELIUS SOCIETY Chairman Position vacant Treasurer Jim Beavis 70 Aylesford Avenue, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3SD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close, London N7 0EF Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Katharine Richman 15 Oldcorne Hollow, Yateley GU46 6FL Tel: 01252 861841 Email: [email protected] Front and back covers: Delius’s house at Grez-sur-Loing Paintings by Ishihara Takujiro The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it. Any breaches of copyright are unintentional and regretted. CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..........................................................................................................5 COMMITTEE NOTES..........................................................................................6 SWEDISH CONNECTIONS ...............................................................................7 DELIUS’S NORWEGIAN AND DANISH SONGS: VEHICLES OF -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Delius Appalachia • the Song of the High Hills

SUPER AUDIO CD Delius Appalachia • The Song of the High Hills BBC Symphony Chorus BBC Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Frederick Delius, 1911 Frederick Delius (1862 – 1934) Appalachia* 35:36 Variations on an Old Slave Song with Final Chorus for baritone, chorus, and orchestra Revised and edited by Sir Thomas Beecham To Julius Buths 1 [Introduction I.] Molto moderato – Tranquillo – 3:47 2 [Introduction II.] Poco più vivo ma moderato – 2:13 3 [Theme.] Andante – 0:29 4 [Variation I.] Un poco più – Moderato – 0:45 5 [Variation II.] Più vivo – 1:00 6 [Variation III.] Molto moderato – Poco più mosso – Lento – Moderato (molto ritmico) – 4:09 7 [Variation IV.] Con moto – Un poco più tranquillo – 0:53 8 [Variation V.] Giocoso. Allegro moderato – Meno mosso. Più tranquillo – 2:42 9 [Variation VI.] Lento e molto tranquillo – Misterioso. Più mosso – Un poco meno – 4:10 10 [Variation VII.] Andante con grazia – Calando – 1:38 11 [Variation VIII.] Lento sostenuto e tranquillo – Un poco più – Tempo I – 2:49 12 [Variation IX.] Allegro alla marcia – Adagio – 1:42 13 [Variation X.] Marcia. Molto lento maestoso – 1:33 14 [Song.] L’istesso tempo – Misterioso lento – Lento – Più mosso 7:43 3 The Song of the High Hills† 28:34 for chorus and orchestra Edited by Sir Thomas Beecham 15 In ruhigem fließendem Tempo – Tranquillo. Very quietly but not dragging – With vigour – Not too slow – Rather quicker – Slower. Maestoso (not hurried). With exultation – 9:27 16 Very slow (The wide far distance – The great solitude) – Slow and solemnly – Very quietly – Slow and very legato – 11:45 17 Tempo I – Più mosso ma tranquillo – With exultation (not hurried). -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’.