EMILIE DEQUENNE and LOÏC CORBERY Member of the Comédie Française

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lineup Berlin 2019 Booth Mgb #9

LINEUP BERLIN 2019 BOOTH MGB #9 1 PANORAMA MIDNIGHT TRAVELER A FILM BY HASSAN FAZILI & EMELIE MAHDAVIAN When the Taliban puts a bounty on Afghan director Hassan Fazili's head, he is forced to flee with his wife and two young daughters. Capturing their uncertain journey, Fazili shows both the danger and desperation of their multi-year odyssey and the tremendous love shared between them. “PARTICULARLY GIVEN THE RISE IN IGNORANCE ABOUT AN ANIMOSITY TOWARDS REFUGEES, IT’S A FILM WHICH DESERVES TO BE AS WIDELY SEEN AS POSSIBLE.” SCREEN INTERNATIONAL Old Chilly Pictures USA - Qatar - Canada - UK / 87’ / 2019 / Documentary Sales for North America: CINETIC PANORAMA SCREENINGS: EFM SCREENINGS: SUNDAY 10/02 17:00 CINESTAR 7 MONDAY 11/02 22:30 CINESTAR 7 SATURDAY 09/02 15:00 CINEMAXX 12 WEDNESDAY 13/02 14:30 COLOSSEUM 1 TUESDAY 12/02 12:45 CINEMAXX 16 FRIDAY 15/02 12:00 CINESTAR 7 THURSDAY 14/02 17:30 CINEMAXX 11 2 3 EFM MARKET WHATEVER HAPPENED TO MY REVOLUTION BY JUDITH DAVIS With: Judith Davis, Malik Zidi, Claire Dumas Angèle, a young and restless activist, never stops crusading for social justice, losing sight of her friends, family and love in the process. EFM SCREENINGS: “A RAGING, HILARIOUS COMEDY.” TELERAMA FRIDAY 08/02 14:45 CINEMAXX 12 MONDAY 11/02 9:30 Agat Films - Apsara Films / France / 88’ / 2018 / Feature Film CINEMAXX 14 4 SLAM BY PARTHO SEN-GUPTA With: Adam Bakri, Rachael Blake, Abbey Azziz Ricky is a young Arab Australian whose peaceful suburban life is turned on its head when his sister, Ameena, disappears without trace. -

Download Catalogue

LIBRARY "Something like Diaz’s equivalent "Emotionally and visually powerful" of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville" THE HALT ANG HUPA 2019 | PHILIPPINES | SCI-FI | 278 MIN. DIRECTOR LAV DIAZ CAST PIOLO PASCUAL JOEL LAMANGAN SHAINA MAGDAYAO Manilla, 2034. As a result of massive volcanic eruptions in the Celebes Sea in 2031, Southeast Asia has literally been in the dark for the last three years, zero sunlight. Madmen control countries, communities, enclaves and new bubble cities. Cataclysmic epidemics ravage the continent. Millions have died and millions more have left. "A dreamy, dreary love story packaged "A professional, polished as a murder mystery" but overly cautious directorial debut" SUMMER OF CHANGSHA LIU YU TIAN 2019 | CHINA | CRIME | 120 MIN. DIRECTOR ZU FENG China, nowadays, in the city of Changsha. A Bin is a police detective. During the investigation of a bizarre murder case, he meets Li Xue, a surgeon. As they get to know each other, A Bin happens to be more and more attracted to this mysterious woman, while both are struggling with their own love stories and sins. Could a love affair help them find redemption? ROMULUS & ROMULUS: THE FIRST KING IL PRIMO RE 2019 | ITALY, BELGIUM | EPIC ACTION | 116 MIN. DIRECTOR MATTEO ROVERE CAST ALESSANDRO BORGHI ALESSIO LAPICE FABRIZIO RONGIONE Romulus and Remus are 18-year-old shepherds twin brothers living in peace near the Tiber river. Convinced that he is bigger than gods’ will, Remus believes he is meant to become king of the city he and his brother will found. But their tragic destiny is already written… This incredible journey will lead these two brothers to creating one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen, Rome. -

Joachim Lafosse Bérénice Bejo Cédric Kahn

LES FILMS DU WORSO AND VERSUS PRODUCTION PRESENT BÉRÉNICE BEJO CÉDRIC KAHN A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE Les films du Worso and Versus production present A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE WITH BÉRÉNICE BEJO AND CÉDRIC KAHN 100MIN - BELGIUM/FRANCE - 2016 - SCOPE - 5.1 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ALIBI COMMUNICATIONS INTERNATIONAL SALES Brigitta PORTIER In Cannes: Unifrance – Village International 5, rue Darcet French mobile: +33 6 28 96 81 65 (from May10th) 75017 Paris International mobile: +32 4 77 98 25 84 Phone: +33 1 44 69 59 59 [email protected] Press materials available for download on www.le-pacte.com SYNOPSIS After 15 years of living together, Marie and Boris decide to get a divorce. Marie had bought the house in which they live with their two daughters, but it was Boris who had completely renovated it. Since he cannot afford to find another place to live, they must continue to share it. When all is said and done, neither of the two is willing to give up. We sense that the two girls are quite disrupted by the situation. At the same time, they give INTERVIEW WITH the impression that they are quite comprehensive regarding the very strict rules imposed by Marie on Boris, just like they’re comprehensive regarding the father’s transgressions: “It’s not JOACHIM LAFOSSE his day”, Jade will tell Margaux, so as to explain the embarrassment which follows Boris’s presence in the house on a Wednesday afternoon. Marie seems to sets all the rules. She’s in charge. Boris does not have a say, but in a way this situation allows What triggered the idea of the film? How did you write it? him to set his own rule. -

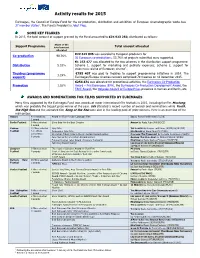

Activity Results for 2015

Activity results for 2015 Eurimages, the Council of Europe Fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematographic works has 37 member states1. The Fund’s President is Jobst Plog. SOME KEY FIGURES In 2015, the total amount of support granted by the Fund amounted to €24 923 250, distributed as follows: Share of the Support Programme total amount Total amount allocated allocated €22 619 895 was awarded to European producers for Co-production 90.76% 92 European co-productions. 55.76% of projects submitted were supported. €1 253 477 was allocated to the two schemes in the distribution support programme: Distribution 5.03% Scheme 1, support for marketing and publicity expenses; Scheme 2, support for awareness raising of European cinema2. Theatres (programme €795 407 was paid to theatres to support programming initiatives in 2014. The 3.19% support) Eurimages/Europa Cinemas network comprised 70 theatres on 31 December 2015. €254 471 was allocated for promotional activities, the Eurimages Co-Production Promotion 1.02% Award – Prix Eurimages (EFA), the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award, the FACE Award, the Odyssée-Council of Europe Prize, presence in Cannes and Berlin, etc. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR FILMS SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES Many films supported by the Eurimages Fund won awards at major international film festivals in 2015, including the film Mustang, which was probably the biggest prize-winner of the year. Ida attracted a record number of awards and nominations while Youth, the High Sun and the animated film Song of the Sea were also in the leading pack of prize-winners. -

2011-Catalogue.Pdf

>> Le Festival existegrâceausoutiende/ Le Festival PARTENAIRES The Festival receives supportfrom receives The Festival SPONSORS 1 192 > INDEX 175 > ACTIONS VERS LES PUBLICS 179 > RENCONTRES 167 > AUTRES PROGRAMMATIONS 105 > HOMMAGES ET RÉTROSPECTIVES 19 > SELECTION OFFICIELLE 01 > LE FESTIVAL PARTENAIRES SPONSORS LE FESTIVAL >> Le Festival remercie / The Festival would like to thank Académie de Nantes • ACOR • Andégave communication • Arte • Artothèque • Atmosphères Production • Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Angers • Bureau d’Accueil des Tournages des Pays de la Loire • Capricci • Films Centre national de danse contemporaine • Centre Hospitalier Universitaire • Cinéma Parlant • CCO - Abbaye de Fontevraud • Commission Supérieure Technique • Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts • Ecole Supérieure des Pays de la Loire • Ecran Total • Eden Solutions • Elacom • Esra Bretagne • Fé2A • Filminger • France 2 • France Culture • Keolis Angers Cotra • Forum des Images • Ford Rent Angers • Héliotrope • Imprimerie Setig Palussière • Inspection Académique de Maine-et-Loire • Institut municipal d’Angers • JC Decaux • La fémis • Les Films du camion • Les Vitrines d’Angers • Musées d’Angers • Nouveau Théâtre d’Angers • OPCAL • Pôle emploi Spectacle • SCEREN – CDDP de Maine-et-Loire • Tacc Kinoton • Université d’Angers • Université Catholique de l’Ouest Ambassade de France à Berlin • Ambassade de France en République tchèque • Ambassade de France en Russie • Ambassade d’Espagne à Paris • British Council • Centre culturel Français Alexandre Dumas de Tbilissi • -

Long Métrage Feature Film

LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM 02/2018 CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE-BRUXELLES IMAGES MINISTÈRE DE LA FÉDÉRATION WALLONIE-BRUXELLES SERVICE GÉNÉRAL DE L’AUDIOVISUEL ET DES MÉDIAS CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL PROMOTION EN BELGIQUE Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 413 22 44 Thierry Vandersanden - Directeur [email protected] www.centreducinema.be WALLONIE BRUXELLES IMAGES PROMOTION INTERNATIONALE Place Flagey 18 - B-1050 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 223 23 04 [email protected] - www.wbimages.be Éric Franssen - Directeur LONG MÉTRAGE [email protected] ÉDITEUR RESPONSABLE Frédéric Delcor - Secrétaire Général Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles COUVERTURE / COVER DUELLES de Olivier Masset-Depasse Production : Versus production © G.Chekaiban LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM 02/2018 CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE-BRUXELLES IMAGES SOMMAIRE CONTENTS BITTER FLOWERS . OLIVIER MEYS . 6 CARNIVORES . JÉRÉMIE & YANNICK RÉNIER . 7 CAVALE . VIRGINIE GOURMEL . 8 CONTINUER . JOACHIM LAFOSSE . 9 DEMAIN DÈS L’AUBE . DELPHINE NOELS . 10 DOUBLEPLUSUNGOOD . MARCO LAGUNA . 11 DRÔLE DE PÈRE . AMÉLIE VAN ELMBT . 12 DUELLES . OLIVIER MASSET-DEPASSE . 13 ESCAPADA . SARAH HIRTT . 14 FOR A HAPPY LIFE . DIMITRI LINDER & SALIMA GLAMINE . 15 LAISSEZ BRONZER LES CADAVRES . BRUNO FORZANI & HÉLÈNE CATTET . 16 MÉPRISES . BERNARD DECLERCQ . 17 NOS BATAILLES . GUILLAUME SENEZ . 18 PART SAUVAGE (LA) . GUÉRIN VAN DE VORST . 19 PIVOINE (LA) . JOAQUIN BRETON . 20 POLINA . OLIAS BARCO . 21 ROI DE LA VALLÉE (LE) . OLIVIER RINGER & YVES RINGER . 22 SEULE À MON MARIAGE . MARTA BERGMAN . 23 SUICIDE D'EMMA PEETERS (LE) . NICOLE PALO . 24 THE MERCY OF THE JUNGLE . JOËL KAREKEZI . -

“Oscar ® ” and “Academyawards

“OSCAR®” AND “ACADEMY AWARDS®” ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF THE ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND USED WITH PERMISSION. THIS IS NOT AN ACADEMY RELEASE. A SISTER BELGIUM /16MINS/2018 Native Title: UNE SOEUR Director: DElphiNE GiRaRD Producers: JacqUES-hENRi BRONckaRt (VERSUS pRODUctiON) Synopsis: a night. a car. alie is in trouble. to get by she must make the most important call of her life. Director’s Biography: Born in the heart of the French-canadian winter, Delphine Girard moved to Belgium a few years later. after starting her studies as an actress, she transferred to the directing department at the iNSaS in Brussels. her graduation film, MONSTRE , won several awards in Belgium and around the world. after leaving the school, she worked on several films as an assistant director, children's coach or casting director ("Our children" by Joachim lafosse, "Mothers’ instinct" by Olivier Masset-Depasse) while writing and directing the short film CAVERNE , adapted from a short story by the american author holly Goddard Jones. A SISTER is her second short film. She is currently working on her first feature and a fiction series. Awards: Jury Prize - Saguenay IFF (Canada) Grand Prize Rhode Island IFF (USA) Best International Short Film Sulmona IFF (Italy) Grand Prize Jury SPASM Festival (Canada) Best Short Film, Public Prize, Be tv Prize, University of Namur Prize - Namur Film Festival (Belgium) Public Prize & Special mention by press - BSFF (Belgium) Best Belgian Short Film RamDam FF (Belgium) Prize Creteil Film Festival Festivals/Screenings: -

Audiovisual Authors' Rights and Remuneration in Europe

AUDIOVISUAL AUTHORS’ RIGHTS AND REMUNERATION IN EUROPE WHITE PAPER Society of Audiovisual Authors Authors: Cécile Despringre Suzan Dormer Special thanks to Marie-Luise Moltmann and all SAA members February 2011 2design: www.delights.be SOCIETY OF AUDIOVISUAL AUTHORS The Society of Audiovisual Authors (SAA) was established in 2010 by European collective management societies to represent the interests of their audiovisual authors’ members and, in particular, screenwriters and directors. The establishment of SAA was prompted by a perceived need to enforce the legal position of writers and directors and to fight for a fair, transparent and harmonised system to remunerate European audiovisual authors for the digital use of their work. Such a system should ensure that all authors are fairly remunerated in line with the success of their films and programmes and, at the same time, allow for easy distribution and access of works. This can only be achieved through the collective management of audiovisual authors’ rights and remuneration. The society has two distinct aims: • To secure an unwaivable right of authors to remuneration for their online rights, based on revenues generated from online distribution and collected from the final distributor. This entitlement should exist even when exclusive rights have been transferred and would secure a financial reward for authors proportional to the real exploitation of the works. • To ensure that the administration of this remuneration is entrusted to collective management societies. This will guarantee that audiovisual authors are paid and establish a direct revenue stream between the market place and audiovisual authors. SAA is committed to working with all interested parties to establish an effective system for the collective licensing and pan-European management of audiovisual authors’ rights and remuneration. -

Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier Olivier Assayas

MK2 presents Juliette Charles Jérémie BINOCHE BERLING RENIER A film by Olivier ASSAYAS photo : Jeannick Gravelines MK2 presents I wanted, as simply as possibly, to tell the story of a life-cycle that resembles that of the seasons… Olivier Assayas a film by Olivier Assayas Starring Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier France, 35mm, color, 2008. Running time : 102’ in coproduction with France 3 Cinéma and the participation of the Musée d’Orsay and of Canal+ and TPS Star with the support of the Region of Ile-de-France in partnership with the CNC I nt E rnationa L S A LE S MK2 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 55 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 [email protected] PRESS MK2 - 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 11 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 SYNOPSIS The divergent paths of three forty something siblings collide when their mother, heiress to her uncle’s exceptional 19th century art collection, dies suddenly. Left to come to terms with themselves and their differences, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche) a successful New York designer, Frédéric (Charles Berling) an economist and university professor in Paris, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier) a dynamic businessman in China, confront the end of childhood, their shared memories, background and unique vision of the future. 1 ABOUT SUMMER HOURS: INTERVIEW WITH OLIVIER ASSAYAS The script of your film was inspired by an initiative from the Musée d’Orsay. Was this a constraint during the writing process? Not at all. In the beginning, there was the desire of the Musée d’Orsay to associate cinema with the celebrations of its twentieth birthday by offering «carte blanche» to four directors from very different backgrounds. -

Festa Del Cinema Di Roma

Sidney Poitier e Paul Newman sono i protagonisti dell’immagine ufficiale della quindicesima edizione della Festa del Cinema di Roma, in una foto FESTA che celebra, oltre al glamour del grande cinema, il senso di comunione e amore interrazziale. Lo scatto, in occasione delle riprese di Paris Blues di Martin Ritt (1961), film candidato all’Oscar® per la miglior colonna sonora firmata da Duke DEL CINEMA Ellington, rappresenta un omaggio a due icone della storia del cinema. Il senso di complicità, la gioia di stare insieme, la condivisione delle esperienze, il valore della collaborazione umana e artistica sono il beat DI ROMA della Festa del Cinema 2020. Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman are the protagonists of the official poster of the 15th Rome Film Fest. This is an image that celebrates the glamour of great cinema but also a sense of communion and interracial love.The photo, taken during the shooting of Paris Blues by Martin Ritt (1961), the film est ® F nominated for the Oscar for Best Soundtrack, composed by Duke Ellington, is a tribute to two icons in the history of film. That sense of complicity, the joy of being together, the sharing of experiences, the value of human and artistic collaboration are the beat of Rome Film Fest 2020. ome Film R oma | R 15 25 10 2020 esta del Cinema di F 20 Edizione 0 2 Edition © Everett Collection Sidney Poitier e Paul Newman sono i protagonisti dell’immagine ufficiale della quindicesima edizione della Festa del Cinema di Roma, in una foto FESTA che celebra, oltre al glamour del grande cinema, il senso di comunione e amore interrazziale. -

De Lucas Belvaux Thierry Horguelin

Document generated on 10/03/2021 6:13 a.m. 24 images Un moderne Feydeau Pour rire! de Lucas Belvaux Thierry Horguelin Number 87, Summer 1997 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/23615ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Horguelin, T. (1997). Review of [Un moderne Feydeau / Pour rire! de Lucas Belvaux]. 24 images, (87), 46–54. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 1997 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ OINTS DE VUE Ornella Muti et Tonie Marshall dans Pour rire! de Lucas Belvaux. 24 IMAGES N 87 POUR RIRE/ DE LUCAS BELVAUX de sorte que sans cesser de nous amuser, les N MODERNE FEYDEAU péripéties loufoques et les accès de pure bouffonnerie burlesque (plongeons répétés PAR THIERRY HORGUELIN dans la Seine, improbables séances de médi tation zen, poursuites désopilantes à moby souffrent, et dont les parcours ouvrent à lette) ménagent une place à l'émotion. l y a le mari, la femme et l'amant. Des l'improviste sur des échappées plus trou La réussire de ce mélange des tons doit I quiproquos et des lettres anonymes, des blantes qu'on y aurait songé. -

Home Front New 05-02 OK.Indd 1 06/02/2020 08:26 SYNECDOCHE Presents

841x1189 Home Front New 05-02 OK.indd 1 06/02/2020 08:26 SYNECDOCHE presents HOME FRONT A FILM BY LUCAS BELVAUX with GÉRARD DEPARDIEU, CATHERINE FROT, JEAN-PIERRE DARROUSSIN, YOANN ZIMMER, FÉLIX KYSYL, EDOUARD SULPICE 2020 - France - Belgium - Color - 101’ INTERNATIONAL SALES IN CO-REPRESENTATION WITH THE PARTY FILM SALES WILD BUNCH INTERNATIONAL 9 Rue Ambroise Thomas - 75009 Paris 65 Rue de Dunkerque - 75009 Paris 01 40 22 92 15 01 43 13 21 15 [email protected] [email protected] www.thepartysales.com https://www.wildbunch.biz/ 1 They were called to Algeria during the “events” of 1960. Two years later, Bernard, Rabut, Février and others returned to France. They kept silent, and lived their lives. Synopsis But sometimes it takes almost nothing, a birthday, a gift in one’s pocket, to bring the past charging back, forty years later, into the lives of those who believed they could deny it. Why did you choose to adapt Laurent Mauvignier’s novel The Wound ? I read The Wound when it first came out more than ten years ago. I found it outstanding, astonishing, moving, powerful. In fact, I wish I’d written it. There is the style, of course - the syncopated, halting writing that gives Interview rise to the tragedy of the insignificant, the ordinary, of silence. Laurent Mauvignier is a great writer, but you can’t adapt a style. You can, however, with Lucas Belvaux adapt a process. Here, it’s in the form of flashbacks, monologues, and non-chronological narration through thought. But beyond that, it’s the developed themes that gripped me because they fall in line with questions that have haunted me for years: the clash of individual destinies and major moments in history, the memories, the guilt, the secret wounds and permanent scars that war leaves in people’s minds.